The decomposition of the international community from its consolidated patterns is becoming a constant element of the current landscape and this makes it very difficult for actors and powers to analyze and manage situations, being them old, new and/or renewed presences, and builds instrumental alliances depending on the areas where interests and crises are concentrated.

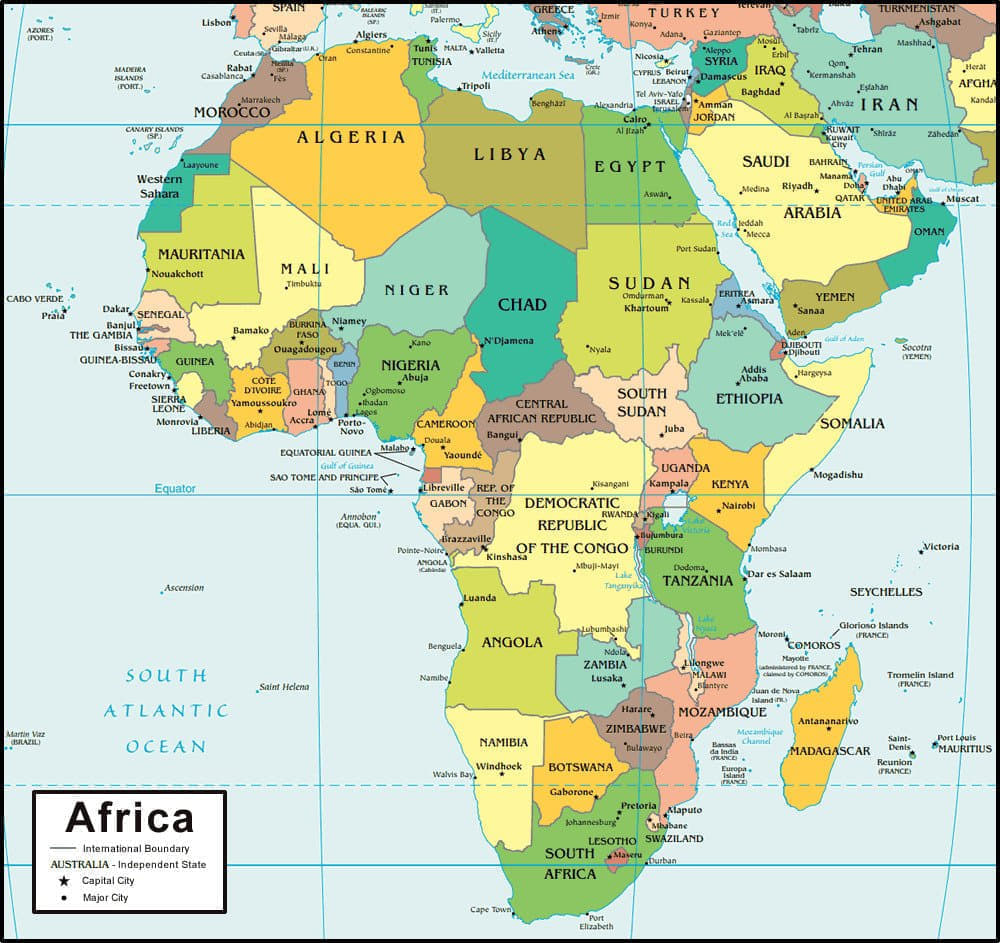

An example of this situation where allies are competitors and competitors can be potential partners is the Horn of Africa, region which currently experiencing high levels of political violence and instability, from the conflicts in Sudan and Ethiopia to Islamist militant activity in Kenya, the al-Shabab insurgency in Somalia to end up with the brutal, and seems endless till now, civil war in Sudan.

This region is proving to be one of the most delicate hubs on the international scene and its dynamics transcend purely geographical terms, but extend their effects to surrounding areas, such as southern and eastern Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian Ocean up to the Mediterranean.

At the center of these dynamics there is a group of states and quasi-state realities, where there are ambitions, attempts to recompose internal cohesion and international image, jarring socio-economic situations, extreme meteorological and environmental phenomena, intrusions of new powers, international and regional organizations always undecided and velleitarian. All this creates a potential mix of instability, but, paradoxically, also of opportunities.

The Horn of Africa, which includes four states (at least those officially recognized), Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Djibouti, is heavily marked by the legacy (at least in three out of four, excluding Djibouti, French, and British for Somaliland) of Italian colonization (colonialism of a poor nation, which has its own characteristics), a failed decolonization, the Cold War, the chaotic post-Cold War and the more chaotic new Cold War of the present days.

The post-World War II systematization scheme held until the 1970s, with the end of the Ethiopian empire, replaced by a pro-Soviet government, while the USSR already had a foot in Somalia since the coup d’état of the dictator Siad Barre in 1970.

In this context, Somalia, precisely because of its geographical location, multiple weaknesses, represents a central hub of regional, pan-regional and beyond, balances and fractures. What are these weaknesses? An institutional reality of a nominal federal structure, a façade to hide a clannish reality, in the process of further disintegration starting from Somaliland, a de facto independent state since 1991 and now Puntland, which looks towards the end of the ‘special autonomy’ of that territory, the ancient Migurtinia (it should be recalled that from this region started the uprising of ‘90 which overthrow the regime of general Siad Barre, in power since 1969).

The recent decision by the Federal Government of Somalia to suspend the provisional constitution, a foundation for unity and state-building, has raised concerns. This decision, made on 4 April of this year, is perceived as detrimental to the original concept of establishing a federal state (in 2012) as only possible wat to push Somalia out of the quagmire where the country is since 1991, the removal of Siad Barre, the explosion of the civil war between ‘warlords’ and the explosion of the armed Islamism. Further, Puntland has affirmed its commitment to engaging with neighboring countries, the international community, and Somalia’s partners.

The other major problem is that of security represented by the threat of Al Shabab and the inability of Mogadishu, precisely due to its mentioned clan reality, to form credible national military institutions, despite a prolonged commitment and, so far not up to various military training missions (UN, USA, EU, UK, UAE, Türkiye) and an African Union (AU) military mission, deployed since 2007 (fully financed by the EU), which suffered heavy losses and only managed to contain the pressure of the Al Shabab. This despite the presence of thousands of foreign military operators, contractors and US regular elements, mostly with members of the special forces, drones (for the US alone we are talking about 2,000 units between instructors, personnel of special forces and drones’ operators).

Now Somalia’s security situation faces a greater challenge, the announced withdrawal of the AU ‘green berets’, which began in 2023 and continued despite several obstacles posed by Mogadishu and planned to be completed in 2024. The Somali government is seriously worried for a security vacuum that could be truly fatal for the African nation.

The shape, size and mandate of a new force to secure Somalia — after the exit of the current African Union peacekeeping mission at the end of this year — remain unknown as it emerges that the Horn of Africa nation is yet to submit its plan before the UNSC (UN Security Council) for consideration and final endorsement.

In a communique issued at the beginning of April, AU said Somalia’s plan for a new force to replace ATMIS (African [Union] Transition Mission is Somalia, which replaced AMISOM, African [Union] Mission in Somalia, the initial deployment of AU-backed troops since 2007, but with limited successes in the stabilization of the country against Islamist terrorists of Al Shabab) will be submitted next month after the continental body undertakes a comprehensive study, and a initial political approval, of the threats and needs on the ground before seeking endorsement of the UNSC.

Mogadishu missed its initial timeline of end of March when it was expected to submit its proposal, due to consultations with the AU PSC (Peace and Security Council) on 26 March and 3 April to plan for the new force that will start operations on 1 January 2025, once ATMIS withdrawal will be completed. Mogadishu indicated only that the ideal force level would be around 10.000 troops.

The AU gave its support to Mogadishu call for a full assessment of the threats and current security needs, in a briefing by Somalia on its proposal for a post-ATMIS security arrangement, pursuant to the UNSC Resolution 2710 (2023).

The new force would be deployed and assume security responsibilities to support Somali security forces on 1 January 2025, a scenario that requires boots on the ground before end of this year to ensure seamless exit of ATMIS troops and immediate replacement.

The AU is keen to preserve the gains that its mission has registered in Somalia for 17 years battling the Al Shabab extremists and (allegedly) liberating more than 80% of Somali territory from the control of the Al Qaeda affiliated terrorist group, the already mentioned Al Shabab.

But as the mission gradually departs the Horn of Africa nation, with periodic drawdown of troops — with another 4.000 troops to leave at the end of June — experts say Somalia remains vulnerable as the country’s efforts for force generation was not synchronized with ATMIS numbers reduction.

Accordingly, the AU underlines the importance of preserving the gains registered since 2007. International partners that have supported the AU mission and the rebuilding of Somalia’s army to take full responsibility of its security, want a “lean mission focusing on supporting the Somali security forces” to complete the country’s transition without creating a new strain on donor budgets, under a serious fatigue.

But the AU also reiterates its deep concern over the ATMIS funding gap — even as the force’s tenure ends in under eight months — stressing the need for adequate, sustainable and predictable funding for the mission, the burden of which, international partners have borne since 2007.

The EU, for instance, which funds the mission (€2.7 billion for AMISOM/ATMIS till now), face competing funding priorities elsewhere, while the AU still looks the same source for “adequate, predictable and sustainable financing to the post-ATMIS force.

In the same period, were recorded an increased number of attacks of Al Shabab attacks against security forces and ATMIS bases, as well as security force operations against the militants.

Last month, particularly in Galmudug and Hirshabelle states, the Somali troops suffered significant setbacks, which led Al Shabab to regain control of several areas after security forces withdrew from several bases, and showing how fragile were the gains of AMISOM/ATMIS and the solidity of regular somali troops, where internal tensions over logistics failures, corruption, and power struggles were reported.

Despite these shortcomings and the low level of political empathy with the Somalian leadership, the international community cannot ignore the dire stability needs of Mogadishu and want to avert any vacuum between ATMIS and the follow force (in whatever format). In the last week of April EU had approved €116 million ($117 million) for stabilisation efforts in Somalia via its Political and Security Committee. The EU added that it would add $75 million to the resources already mobilised for ATMIS in previous years, covering July 2021 to December 2023, specifying that previous support to the peacekeepers under the EPF (European Peace Facility, an off-budget EU financing tool set up in March 2021, which aims towards the delivery of military aid to partner countries and funds the deployment of EU military missions abroad under the Common Foreign and Security Policy, ECFSP) amounted to €270 million ($271 million). The agreed funding for Somali National Army amounts to €42 million ($43 million) while, according to the EU, “Previous support to the SNA under the EPF amounts to €50 million ($51 million).” This came as the UK announced a contribution of $2.8 million in support of Somali security forces via the UNSOS (UN Support Office in Somalia).

Britain already provided $29.17 million of voluntary contributions in support of UNSOS since 2022 and provides financial support to the ATMIS, which in the while has fulfilled the first two phases of its drawdown of 5,000 troops, handing over 13 FOB (Forward Operating Bases) to Somalia security forces since the beginning of 2023. The next drawdown of peacekeepers is expected to be 4,000 before end of June 2024.

But for Mogadishu, security is also undermined by unresolved internal issues and, as mentioned, external intrusions. And the recent events in Somaliland are a perfect example of this.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali, who survived the Tigray insurrection, and with revolts that risk taking on similar proportions in the Amhara region (the heart of the Ethiopian ethnic group and nation), has done research since his inauguration in 2018 of his country’s access to the sea an existential question. Last October 13th he described the situation in Ethiopia as a geographical prison from which it need be freed.

Landlocked since 1991 following Eritrean independence, Ethiopia is in vital need of a maritime opening, which involves either returning the port of Assab, at Asmara’s expense, or having access to it as a free port free from Eritrean customs. But given the difficult relations with Eritrea, Addis Ababa is looking elsewhere, such as facilities in the self-proclaimed state of Somaliland.

Addis Ababa announced an agreement with Hargeisa on 1 January, but without providing many details. It is useful to remember that in 1950 Eritrea, from 1941 under British military government, was federated to Ethiopia, through a vote of the UN General Assembly, as compensation for the Italian invasion and reward for the decisive pro-Western position of the late emperor Haile Selassie; Ethiopia was committed to keeping Eritrea a federated entity; in 1962, with a unilateral act, Addis Ababa formally annexed Eritrea, without any international protest.

The situation deteriorated when the pro-Soviet communist regime led by Menghistu Haile Mariam came to power in 1974 with a coup that deposed the emperor. The head of the Derg (the military junta) initiates a ferocious repression against the Eritrean independence movement, but also against the Somalis of the Ogaden, the populations of the Oromo and Tigray. The repression is so ruthless that the various resistance movements band together and lead to the fall of that bloody regime, despite the help of Soviet ‘advisers’ and Cuban troops.

In 1991, Ethiopia became a federal state and Eritrea became fully independent, but the bilateral relations, after a promising start, quickly became difficult and led to open war between 1998 and 2000. As evidence of the fluctuating relations between Addis Ababa and Asmara, on the occasion of the recent revolt in the state of Tigray, the intervention of the Eritrean forces saved Ethiopia from military collapse in the face of the Tigrayan offensive.

After this interval, bilateral relations returned to the bad and Aby Ahmed Ali realized that an outlet to the sea, moreover into a closed basin like the Red Sea and, as can be seen in this phase due to the strike of Yemenite Houtis militias against international maritime trade, was a weak option. Aby Ahmed turned his gaze and action elsewhere and the choice of Somaliland seemed obligatory and better than the port of Assab; firstly reduce the contacts with a ‘pariah’ state as Eritrea; secondly, it would give Ethiopia direct access to the Indian Ocean and international maritime trade routes.

Especially now that Ethiopia participation in the Russian-Chinese influenced BRICS group of states became effective on 1 January as well.

But this agreement impacts on a difficult geopolitical situation. Also, in this case it is useful to take a quick look at the past to better understand the present and ask questions about the future.

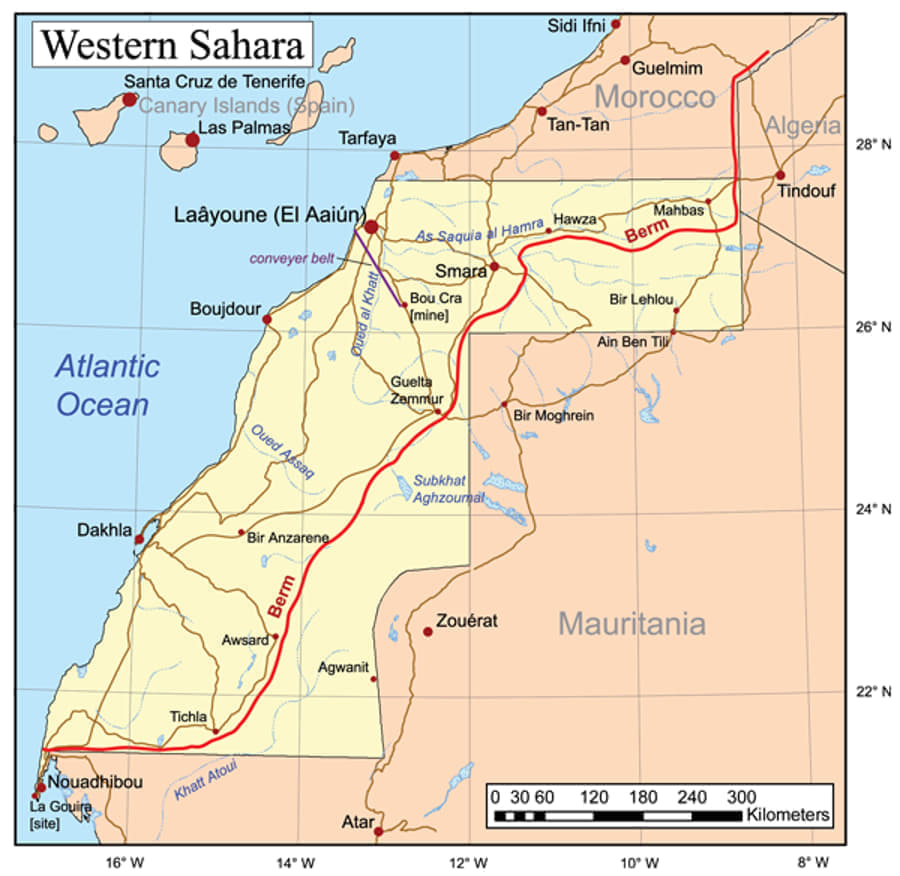

Somaliland is the former British Somalia and after the end of the trusteeship of Rome over the former Italian Somalia assigned by the United Nations (between 1950-1960 and started when Italy was not even part of the organization, joined only in 1955), it was united with Mogadishu, but always remaining a peripheral and little-considered reality. This situation promoted and preserved the existence of pro-independence groups.

When the regime of Mohammed Siad Barre, in power since 1969, collapsed in 1991, Somaliland took the opportunity and proclaimed itself independent and sought international recognition and attempted to assert the fact that, although for a very short period (less than one week), the former British colony was in fact independent before being united with Somalia.

So far, this project has had very little success despite Somaliland’s enviable strategic position. In fact, only Taiwan has established diplomatic contacts with Hargheisa; the very strong ties with the UAE, which has port and military installations in Somaliland to support its operations in Yemen, have not led to the expected diplomatic recognition. It must be said that Somaliland has nevertheless made good use of its independence, ensuring political stability, economic and social development, democratic openness, and respect for electoral and democratic rules and, above all, the absence of Al Shabab terrorists, who instead infest Somalia.

Somaliland has seized a window of opportunity by focusing on Ethiopia’s strategic interest in exchange for what it has stubbornly sought for more than thirty years: to unblock, even formally, its isolation.

But the agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland did not arise out of nowhere; already in 2018, Hargeisa, Addis Ababa and Dubai had signed an agreement for the development of the port of Berbera, the largest port of the small state (but this agreement was preceded by a bilateral one between the UAE and Somaliland, signed in 2017, which allowed the ‘little Sparta’ of the Arabic peninsula to open a military base on African soil).

In exchange for a coastal window in the port area of Berbera, on the coast of the Gulf of Aden and at the mouth of the Red Sea, Ethiopia would have committed to recognizing the self-proclaimed republic of Somaliland. With the signing of a memorandum of understanding on 1 January 2024, Somaliland grants Ethiopia 20 km of its coastline for a period of 50 years (renewable).

The second most populous country on the African continent with 120 million inhabitants, Ethiopia has 90% of its foreign trade passing through the port of Djibouti with an annual cost of around 1.5 billion dollars in custom duties.

The need of a free harbour, cheaper than the cost of Eritrean customs have a strategic relevance for the Ethiopian economy and its stability. Aby Ahmed needs a sustained economic growth other than the skyline of Addis Ababa; the dissemination of the socioeconomic development is a way to pay and buy the social and tribal calm in order to compensate his program to dismantling the federal nature of Ethiopia and cutting the nails at the states resistances.

The details of the agreement, presented on 1 January in the Ethiopian capital by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali and Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi, will have to be revealed later and it is still unclear precisely which part of the coast should come under Ethiopian control, but the cities of Zeilah and Zughaya, not far from Djibouti, have been mentioned by several sources. Addis Ababa plans to build a commercial port, a naval base, an industrial development zone and a road corridor.

This decision by Ethiopia leads to the effective revival of the national naval forces. In fact, the Ethiopian Navy, was reactivated in 2019, is making preparations to establish a naval facility in Somaliland. The Ethiopian navy, one of the most skilled naval forces on the continent, was disbanded in the early 1990s when Ethiopia lost its coastline to the separation of Eritrea. The restoration of the naval force was one of the first initiatives undertaken by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali when he assumed office in early 2018. Over the past five years, with the assistance of friendly nations (which were not disclosed), the Naval Force was formally re-established, with efforts concentrated on the organization of the structure and the training of officers and staff, and the first activities took place, such as the dispatch of relief teams for the Somali populations affected by catastrophic floods.

The Ethiopian Naval Force is currently training its personnel overseas and plans are underway to establish a naval training facility, academy and navy headquarters. For his part, Hargeisa is expected to acquire shares in two thriving Ethiopian companies, Ethiopian Airlines, Africa’s most profitable airline, and telecommunications giant Ethio Telecom. But Somaliland hopes above all that the agreement with Ethiopia will open the way to other diplomatic relations, to be officially recognized as a sovereign state and to emerge from the galaxy of states ignored by the international community.

For its part, the Mogadishu government has denounced a flagrant violation of its sovereignty over a separatist territory not recognized by the international community and announced that Somalia will defend its territory by all means. He also recalled his ambassador to Ethiopia in response to what he considers a unilateral act that endangers regional stability; then expelled the Ethiopian ambassador and ordered to close the Ethiopian consulates in Somaliland and Puntland, which both openly ignored.

The Puntland State makes it clear that it will continue its engagements with neighboring countries, the International Community, and Somalia’s partners adding that the decision to close the Ethiopian Consulate in Garowe does not apply to Puntland. Further, Somaliland consider that the diplomatic representation of Ethiopia is now at the ambassadorial level, after the agreement of 1 January and also threatens the use of force and in the meantime Mogadishu appealed to the IGAD (Intergovernmental Authority on Development, a regional body that brings together Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia, Djibouti, Kenya and Uganda) which however took a Pilate-like position, awaiting further developments.

Meanwhile, Mogadishu is widening its diplomatic offensive (some analyst says that Somalia has only those) as much as it can, also appealing to the EAC (East African Community, recently joined) and the NAM (Non-Aligned Movement) and similar initiatives are planned at the African Union, United Nations, International Court of Justice, African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and the Arab League.

Mogadishu has never accepted the independence of Somaliland, however Somalia’s hopes of bringing Somaliland (and the ‘autonomous’ Puntland) back under its control, even if in a federal form, are very limited, due to its political weakness, institutional, economic and military.

In this perspective, the approach of the Somalian president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, recall a lot the ones of the Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed, who tried to empty the federal system of his country and replacing it with a more centralized system. The first answer to this strategy was the violent uprising of Tigrai, which risked to topple him, and the groving turmoil which across Oromo and Amhara states, which openly refuse the disbandment of their own state forces.

Under general point of view, when there are ongoing strong separatist trends, a federal system, instead of control those and bring it back in a harmonious and constructive balance, risk to exacerbate it and bring to a serious fragmentation and instability. In both Ethiopia and Somalia, the federal system clearly shows a poor approach which exasperated the already existing tensions. The problem is that, between the two, Somalia appears more fragile and with more limited options.

A military action by Mogadishu towards Somaliland, as well as being unlikely, would risk involving Ethiopia, which already has troops in Somalia in ATMIS (thousands of Ethiopian soldiers with the ‘green helmet’ garrisoning Bay, Bakool and Gedo regions and some areas of the Hiiraan and Galgaduud regions, even these areas are largely under the security responsibility of the Djibouti Armed Forces), but there are other thousands Ethiopian troops out of the AU framework and operate under the aegis of a previous bilateral agreement between Addis Ababa and Mogadishu, always focused to fight the Al Shabab.

One option in the hands of Mogadishu would be to ignite the rebellious forces of the Somali-speaking populations of the Ogaden, as well as accentuate the intolerance of the Dhulbahante clan, located between Somalia, Somaliland, Puntland and Ethiopia; but a harsh reaction from Addis Ababa would be foreseeable with the risk, however, of being fuel for the fire of other ongoing regional revolts which would risk breaking up East Africa and all the surrounding areas, which already have their own problems, starting from the ferocious civil war that is tearing Sudan apart, and the other civil war which, even now silenced, still affect South Sudan.

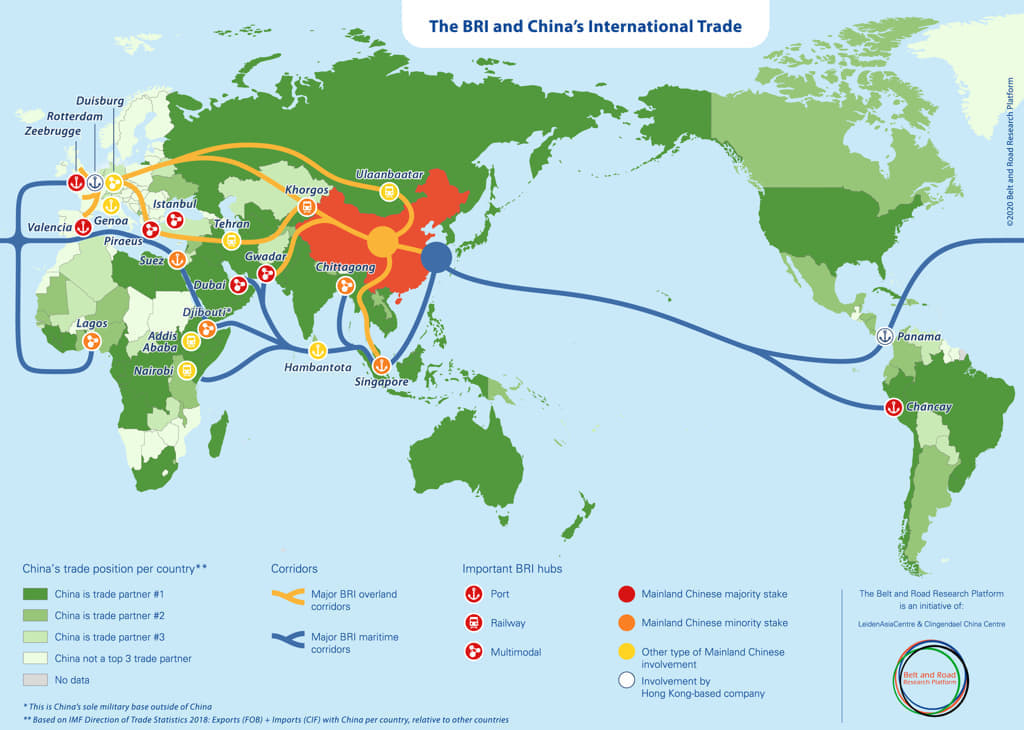

The agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland is looked favorably by Russia, which has already allowed Ethiopia and the UAE join the BRICS and sees its regional position being strengthened and threatening, even if indirectly, the jugular routes of maritime traffic towards Europe and the Mediterranean. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that Eritrea is a faithful ally of Moscow. As is clear at this stage, the agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland is part of a complex regional context. In Djibouti, although there are French, US, Japanese and Italian bases (other NATO and EU countries make extensive use of these bases), there is a Chinese military installation. As for it, the general context remains difficult, and there is the risk that other actors will enter, complicating the situation.

In fact, almost a month after the agreement between Addis Ababa and Hargeisa, Egypt also appeared on the scene; President-Marshal Al Sissi expressed a harsh judgment on the agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland, clearly expressing support for Mogadishu. Behind Egypt’s position is the unresolved issue of the construction of the GERD (Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam) on the Blue Nile River, which has been going on with ups and downs for 12 years. It could appear realistic that Egypt wants to use the triangular dispute to put pressure on Ethiopia and make it be less drastic and participatory in the management of the waters of the Blue Nile which Cairo absolutely needs for its economic development and social stability.

Furthermore, there is the situation in Yemen, divided and in the hands of de facto warring factions and one of them, the Houthis, in conflict in 2014 against everyone (or almost everyone) and avalanche effects are feared. Finally, after a too short pause, threats that were thought to be overcome, but which the very difficult economic and social situation in Somalia has caused to re-emerge, such as piracy. The IMB (International Maritime Bureau) of the ICC (International Chamber of Commerce) recently advised shipping companies and operators to remain vigilant while transiting waters off Somalia and the Gulf of Aden. Since November several ships have been seized off the coast of Somalia, with some still held hostage, showing that Somali pirates have rebuilt their capability.

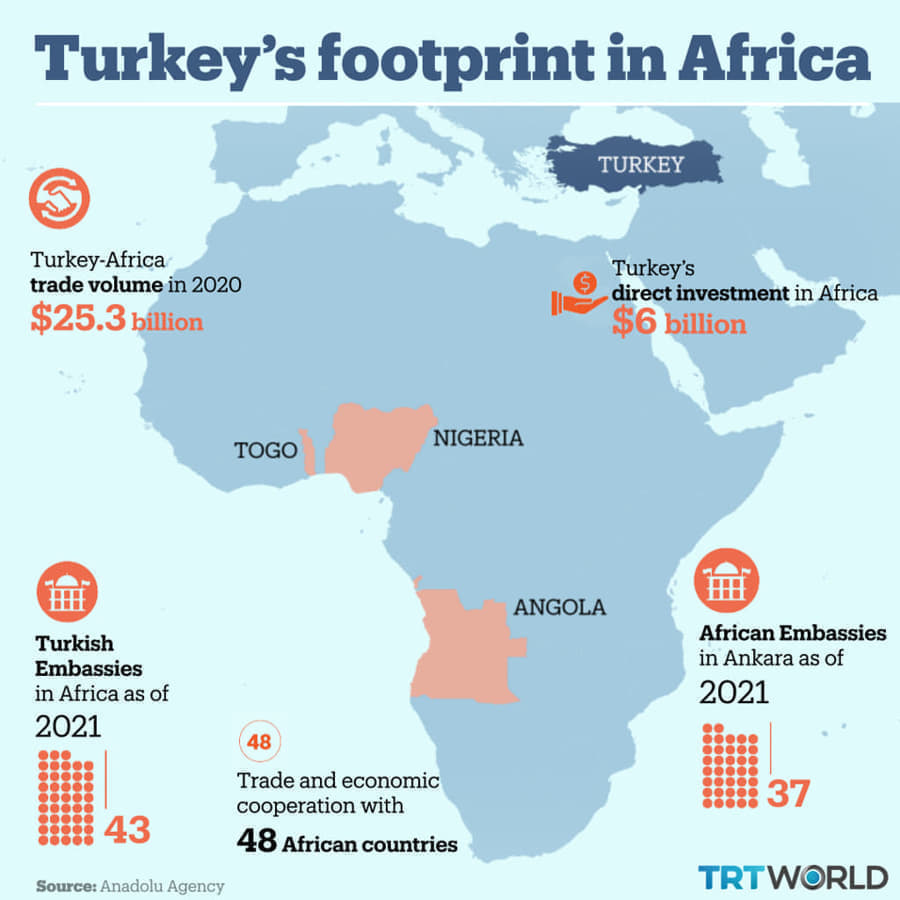

Somalia is trying in every way to strengthen its position and find partners who can help it get out of a humiliating situation. In early February, Turkish Defense Minister Yasar Guler and Somalia’s Defense Minister Abdulkadir Mohamed Nur signed a framework agreement on defense and economic cooperation between two countries in Ankara. The agreement, which adds to the previous ones (2009, technical cooperation agreement; 2010 training cooperation agreement, scientific and technical cooperation; 2012, training and cooperation agreement; 2015 defense industry agreement) as well as starting a training program of the Somali navy, aims to improve Somalia’s security perception and at the same time supports Ankara’s ambitions to project maritime power beyond its shores. The agreement falls within a regional context weakened by the recent agreement between Ethiopia and Somaliland to give Addis Ababa access to the open sea in exchange for the establishment of bilateral diplomatic relations.

The two nations have released few details on the terms of the agreement. What is certainly known is that Turkey will support Somalia in training and equipping its small navy, thus expanding the impact of the training mission of the Turkish army that has been operating in Mogadishu since 2017. Mogadishu, despite all its problems, has launched in a massive diplomatic offensive to counter Addis Ababa’s initiative and to give legitimacy to its claims on a territory that Somalia considers secessionist and illegal. But there is more behind the naval agreement than just a simple deterrent for Ethiopia by Somalia. It is also about Turkey’s long-standing ambitions to project its power in the Red Sea region and pave the way for further defense deals in the region in the future and the culmination of more than a decade of Turkish involvement in Somalia.

This involvement focused on a broad project of nation-building, security sector reform, humanitarian assistance and socio-economic development at a time when Somalia was a nation forgotten by the international community. The agreement aims to secure mutual interests, positioning Ankara as a significant player in the strategic dynamics of the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa in times to come. This can also be seen as part of Ankara’s hard power projection capability and its advanced defense policy.

Through the agreement with Somalia, Ankara will further strengthen its defense ties with Mogadishu, which will bring benefits for the Turkish defense industry and Turkish commercial interests, while consolidating Turkey’s military presence in the strategic Horn Africa and the Red Sea. Ankara is already a regional power, active in the southern and eastern Mediterranean, in Libya, the Sahel, Central Asia, the Gulf, Syria and Iraq. It has the second largest armed forces in NATO and a very effective and active diplomatic corps that is based on a vast network of embassies, consulates and specialized institutions. The expansion of its naval presence in the Red Sea is the logical next step and it is not impossible to even imagine a future naval base in Somalia, to match ‘Turksom’ (the name of the Turkish training compound in Mogadishu).

As mentioned above, the agreement with Somalia, beyond the security needs of Mogadishu, is for Turkey a part of the broader national strategy to protect its supply chains and create strategic depth in the maritime sector and in this is the materialization of the 2021 ‘Mavi Vatan’ maritime strategy which is corroborated by recent orders for a second aircraft carrier (with a larger displacement and capacity than the ‘Anadolou’, currently in service and due to the expulsion of Ankara from the F-35 Lighting II programme, carrying only helicopters and drones) and four other frigates. ‘Mavi Vatan’ is a strategy that aims to re-establish Turkey as a maritime power with a reach well beyond the eastern Mediterranean and beyond its immediate coasts to develop a deep-sea Navy with a strategic reach and depth ranging beyond the Mediterranean, to the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean.

However, reflecting the persistent ambiguity of Turkey, originated by the requirements of multiple alignment of Ankara, despite a verbal acknowledgment of the territorial integrity of Mogadishu, the hopes of Somalian president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, to see a Turkish navy squadron showing the flag in front of the waters of Somaliland and Puntland remain pure theory, despite a visit of Turkish Navy warship to Mogadishu on 24 April and the promise to assist the country to build up a navy (and apparently putting an end to a similar project launched by the Italian Minister of Defence).

After trying to block it in every way, Somalia had to accept the option of withdrawing the ‘green berets’ of ATMIS. Aware of the weakness of its armed forces, Mogadishu looks anxiously for every possible gap filler, and in case of a weak answer of AU for a post-ATMIS operation, may consider that Ankara in the perennial search of affirmation (or self-affirmation), it would be interested in support her security needs and maybe being the leading nation of another anti-Shabab coalition.

Turkey, in the eyes of some Somali leaders, could represent an alternate option in security provider in case that the ATMIS option will fail. Mogadishu is already thinking about and whose terms should be made known after the summer.

But the relations between Mogadishu and Ankara, as confirmed by the large number of agreements, include of course the economic dimension, or better say, the exploitation of natural resources (in this case hydrocarbons) by the stronger partner who leave royalties to the weak one.

Somalia says Turkey will begin drilling oil off the country’s massive coastline from next year, according to the Director General of the Somali Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources, Mohamed Hashi Abdi ‘Arabey’, who confirmed the recent assertion by a Turkish official on a plan for deep-sea oil drilling operation from early 2025. They will begin seismic works and drilling at the coasts facing Barawe and Hobbio districts (Barawe is about 200 km south of Mogadishu while Hobbio is about 500 km to the northeast). In addition to the inclusion of Turkey in the Red Sea-Bab el Mandeb Strait chessboard, the renewed rivalry between Ethiopia and Somalia regarding the future Somaliland has awakened another significant problem.

In fact, both Ethiopia and Somaliland, in addition to agreeing on the issue of the portion of territory that should be leased to Addis Ababa, have also agreed on the management of commercial air traffic control, creating an unclear situation as various and sometimes contradictory, instructions to airlines, which found themselves forced to modify the routes of their aircrafts and reducing access to Somali airspace, bringing to the surface the jurisdictional and political problem of who (really) controls the airspace of Somalia and whether or not this includes Somaliland.

For many years, the unstable political situation in Somalia has had a serious impact on the country’s aviation sector. The previous national airline, Somali Airlines, also suffered due to civil war in the early 1990s. However, following improvements in some areas, last year the airspace over Somalia was reclassified to “Class A” (therefore normal) and saw the return of air traffic control services to the country after three decades. Also highlighting the progress made by the aviation sector, Somalia recently opened its first MRO (maintenance, repair and overhaul) center in over 30 years and therefore now has a facility to repair and inspect aircraft locally. The airspace over Somalia and the surrounding ocean is managed by the SCAA (Somali Civil Aviation Authority) from the Mogadishu Area Control Center, which claims to be able to exercise its jurisdiction also over Somaliland, which instead it refuses on the grounds that it has its own independent state.

This airspace, known as the Mogadishu FIR (Flight Information Region ) and its controlling authority are defined in the ICAO (International Civil Aviation Organization) Air Navigation Plan for the Africa and Indian Ocean Region (AFI), which recognizes Somalia (including Somaliland) as the controlling state, and by extension, the Somali Civil Aviation Authority, and this position is also shared by the IATA (International Air Transport Association), the umbrella organization airlines around the world. Somaliland has control over its airports but the question of airspace remains effectively open.

Egal International Airport (HGA) is the state’s main airport and serves the capital Hargeisa. Following the signing of the Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU, Somali authorities began restricting flight activity in Somaliland to assert their authority over their airspace. As a result of the ongoing litigation, on January 17, the SCAA blocked an Ethiopian Airlines aircraft carrying Ethiopian diplomatic delegates from entering the airspace, saying it did not have permission to enter the country. According to media sources, the SCAA also blocked an air ambulance carrying a Somaliland citizen who “needed urgent help”, in violation of the rules that govern international civil aviation in such cases. However, Somali authorities have denied this latest claim.

In return, Somaliland claimed independence and jurisdiction over its territory and surrounding areas, issuing an international aviation warning and a statement on its X (formerly Twitter) page. Since both states claim the right to control traffic, there have been numerous reports of airlines receiving conflicting instructions while flying over the area from people posing as ‘air traffic controllers’ and risking collisions. It is not entirely clear whether this was also the result of the dispute between the controllers of Mogadishu and Hargeisa.

This was followed by a February 19 statement in which Mogadishu accused Somaliland of disrupting air routes used by aircraft over portions of the airspace of the northern regions of Somalia. The Somalian government added that if these offensive measures continue, Mogadishu will take strong measures to ensure the safety and security of Somali civil aviation. The dispute has also saw obscure events such as the murder of an civilian air traffic controller of the Hargheisa airport in Mogadishu and Somaliland’s protest over the arrest of six people from that territory by Somali police.

The fate of operations in Somali airspace is almost as delicate as that of maritime traffic between the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. The East African area is one of the busiest on the continent. The region is also home to some of Africa’s largest airlines, including Ethiopian Airlines and Kenya Airways. Some of the major airlines connecting the African subcontinent south of Ethiopia with destinations in the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent pass through Somali airspace.

The same applies to air connections between Western Europe and the islands of the Indian Ocean. As IATA has stated, no airline would fly in unsafe airspace and signaling the worsening situation, Ethiopian Airlines has announced that it will change some of its routes to avoid Somali airspace. For airlines still flying to the country, crews have been advised to pay attention to the environment and follow the instructions contained in the NOTAM issued by the Mogadishu authorities which advise them to contact the Mogadishu Area Control Center in particular in the area within a radius of 150 nautical miles from Hargeisa.

Despite several attempt to reorganize the state, like blocking illegal fishing in its territorial waters (that is a real challenge giving that the coast guard and maritime police have mere ‘brown waters’ capacities), Mogadishu and make public the improving financial situation, thanks to erasure of debt from countries like Russia, Somalia is banking on new opportunities coming out of recent debt relief to seek new credit lines and open up for trade.

Last year, Mogadishu was the only East African country that had zero debt after all the debts were forgiven by the World Bank and IMF (in blatant rivalry with the cancellation of debt decided by Moscow in occasion of the last Russia-Africa summit on last July, around 600 million of US$; but not only Moscow, cancel the Mogadishu debt, also London; in fact, without providing details on the amount, UK has cancelled 100% of its Somalia’s historic debts). It gave a fresh start and opens a huge market for East Africa. In December, Somalia reached an agreement to cancel $4.5 billion of debt with international lenders. That, the diplomat says, gave it new opportunity to attract investors as well as be eligible to borrow more from lenders.

So far, Mogadishu has been cautious of simply piling new debt and officials have said they will prioritise opening up and rebuilding state institutions instead. In the month of April, Somalia signed a financial agreement with the IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development, a Rome-based UN specialized institution) which will see Mogadishu receive up to $31.22 million for support programmes related to food security in rural areas. The money is to be channelled under the Rural Livelihood Resilience Programme, aimed at improving food security and resilience in rural areas. The funding will the first direct investment by IFAD in Somalia since Mogadishu’s external debt pile was cleared. Despite the finance portfolio’s optimism, it expects that global problems affect the country both directly and indirectly.

In mid-March this year, representatives of the Paris Club met with representatives of Somalia government and reached consensus on a debt cancellation. The Club’s announcement indicated that debt cancellation came as a result of the Horn of Africa country reaching its Completion Point under the Enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (Enhanced HIPC) Initiative approval by the Executive Boards of the IMF and the World Bank in December 2023.

The debt owed to Paris Club creditors was estimated to be $2 billion as of January 1, 2023, which means 99% of that is now forgiven by the creditors.

However, the regional perspectives are complex. The problems of Somalia seem endless and not limited to the relations with Ethiopia, Somaliland and the collapsing of the federal system. Also, Puntland, which for years remained in a kind of political limbo, not independence but within a special ‘autonomy’ (not octroyed by Mogadishu, but self-gained), showed the fragility of attraction and coercion capability of Mogadishu.

The (Federal, nominally) Government of Somalia’s military toothlessness is responsible for its impotence; instead of focusing on rectifying the former ahead of the foreseeable terrorist upsurge that’ll follow the withdrawal of foreign forces, Mogadishu saber-rattling against Somaliland, Ethiopia, and Puntland are a distraction. As above-mentioned, the Government of Somalia demanded that the autonomous State of Puntland close the Ethiopian consulate in the regional capital of Garowe as part of Mogadishu’s latest diplomatic move to protest January’s Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Ethiopia and Somaliland. Mogadishu also expelled the Ethiopian ambassador and his diplomatic staff alongside demanding the closure of that country’s consulate in Somaliland’s capital of Hargeisa. While the refusal of Somaliland to comply with Mogadishu instructions are understandable giving the precedent situation, the reject of Puntland is more surprising and widely based on the evolution of the situation between Addis Ababa, Hargeisha and Mogadishu. Garowe see in that a momentum which will reinforce its, never hidden, hopes to complete the independence path.

Somalia is powerless to impose its declared writ over those two regions that it still claims as its own, with this latest development exposing just the impotency of Mogadishu. Neither of Ethiopia’s traditional rivals appear really interested in joining Somalia in his efforts for reconquering Somaliland, and even his country’s Turkish military ally, even promising, could be hesitant into to get involved. About that Ankara despite the symbolic visit of its ship to Mogadishu, it still has close ties with Ethiopia despite signing a maritime security deal with Somalia in late February.

As said, even if Ankara officially regards both Somaliland and Puntland as part of the Somalia, yet it hasn’t signaled that it’ll dispatch warships to their waters (nor has Mogadishu officially requested this either, also maybe to avoid another humiliation in getting this request pushed back). The impression is that the Mogadishu barks loudly but doesn’t bite, not because it doesn’t want to do the latter, but simply because has not an autonomy military capability and there are few countries interested in involvement on behalf of a partner without capability, regardless its strategic relevance. The country’s security is dependent on those foreign forces that assist it in trying to degrade Al Shabab military potential, but their substantial reduction by the end of the year will likely lead to an explosion in terrorism. Instead of preparing for that, the Somalian leadership would rather indulge in distractions and saber-rattling, while insisting in the dismantling the fragile federal architecture and preparing for the potential blow of another civil war between new ‘warlords’.

There is a concern that spewing ultra-nationalist rhetoric can bring the Al Shabab militias, which are proved to be very efficient and deadly, onto its side as an “ally of convenience” for waging hybrid war against Somaliland, Ethiopia, and soon possibly Puntland as well. If the terrorists can’t be co-opted through these means, for obvious reasons, the threat of Islamist remain and in long-medium perspective Somalia risks to be like the erstwhile Western-backed Islamic Republic of Afghanistan did in summer 2021 and with the possible emerging of another “emirate” (of terror). This is a nightmare scenario of epic proportions giving the importance of the Horn and the possibly impending fall of Mogadishu under the evil influence of Al Shabab could open a Pandora’s Box of security threats if then-erstwhile Somalia becomes an ungovernable terrorist sanctuary.

Enrico Magnani, PhD, is a retired UN official and expert in military history and international politico-military affairs.