The decomposition (or re-composition) of the international community always follows new paths and not all of them are coherent and/or (still) clear. It is a matter of fact that various actors, whose capabilities and reliability (and their own stability) are not yet known, appear on the scene and bring new elements to specific areas. One of these is Africa, where those of the ‘Scramble for Africa’ reappear in new terms, a phase which for about eighty years, approximately 1830 and 1911, saw the powers, all European, compete to grab territories and wealth of that continent.

While much is known (or assumed to know) about the ambitions of Russia, China, but also about the aspirations and ambitions of France, USA, Turkey, India, EU and others, little is known about those of the Gulf nations. These, within the multiple area of the Arab-Islamic world, due to peculiar circumstances, starting with the enormous financial resources, represent a world apart from that jagged community that goes from the Atlantic to Mesopotamia.Till now deployed in the so-called Western world, these nations have been trying for some time to find an autonomous way from the cumbersome partnership with the USA and Europe, also trying to increase their influence in Africa and also placing themselves in competition with Washington and Brussels. This analysis refers more to the member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) than to the organization as such, which beyond the sumptuous and unrealistic meetings, is little more than a box of fictional cigarettes “Morley.”

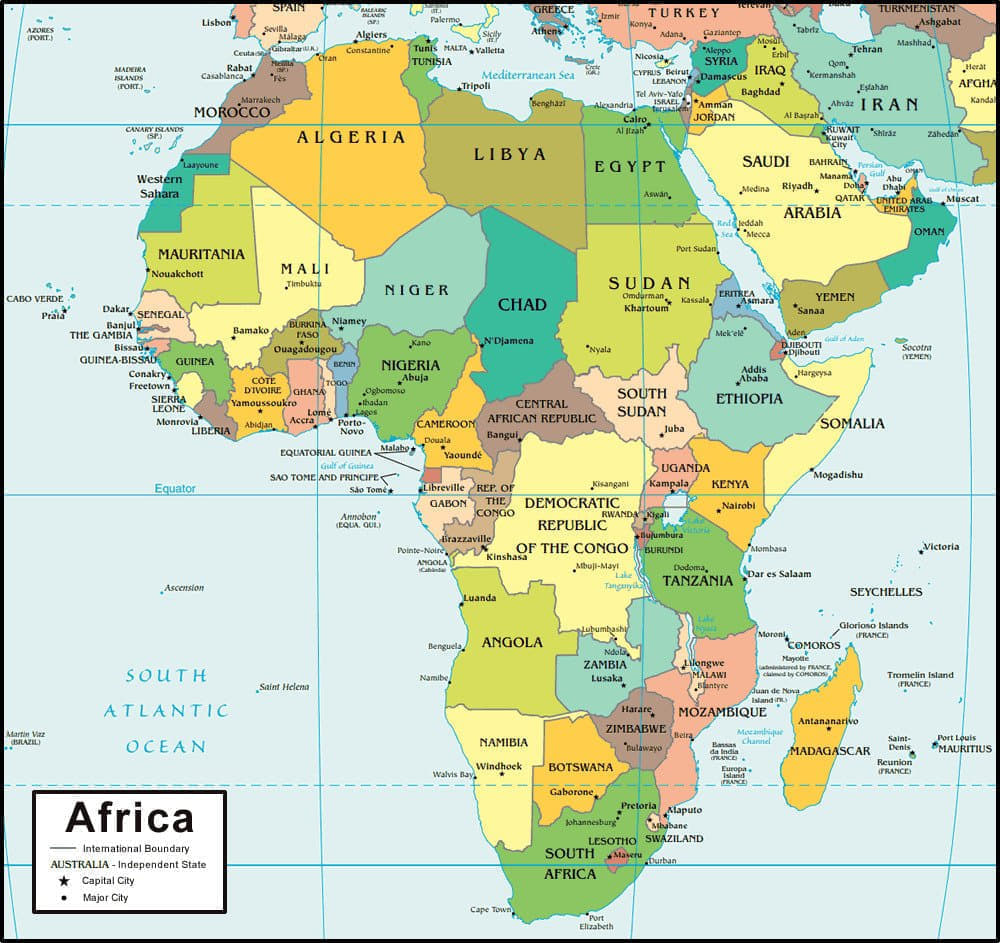

Historically, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have had the most interactions with sub-Saharan Africa (defined as those areas of the continent south of the Arabic-speaking North African states located on the Mediterranean) while Bahrain has the least of all. Oman has historical ties to the east coast of Africa, while Qatar has become more active on the continent especially since its rivalry with Saudi Arabia and the UAE heated up in 2017, due to the military ties of the Qatar with Turkey, too much lining with Iran and Islamist terrorist organizations. Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE became active on the African continent during the 1970s, particularly after the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, when many African countries severed diplomatic ties with Israel due to the arrival of Israeli troops across the Suez Canal.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE launched development aid policies in Africa and even worked towards the same purpose as Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi on the continent, where he had big plans, when the activities were aimed at garnering support for the Arab world in its conflict against Israel. Since then, investment and trade policies, as well as countering the activities of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Africa, have become more important to Saudi Arabia and, in more recent years, the UAE and Qatar rival the Saudis in these efforts and in considering Turkey and Iran as direct rivals for influence on the African continent, despite an (apparent) improvement in relations.

In the last fifteen years, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar have strengthened economic and security ties with the African continent, primarily in the Horn of Africa region and progressively extending them towards sub-Saharan Africa. Saudis, Qataris, Emirates are working in this region with the aim of building the status of their international status by acting as protagonists in the affairs and conflicts of the continent, but it is essential to underline this not in the framework of cooperation between them, rather of more or less open rivalry and the understandings that have been registered are due to tactical necessity, as in the case of Sudan. As mentioned above, although Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar have a tradition of contacts with African realities, the 2007 global financial crisis was the booster to redirect their investments towards Africa. As Western economies slow down, rapidly growing African economies have become attractive bait.

The Gulf monarchies, always in competition and never in solidarity, have strengthened their strategies of economic diversification and reduction of dependence on hydrocarbons by investing in African markets, especially when oil prices collapsed in 2014. The Gulf companies’ experience in the energy sector makes them particularly attractive to African states seeking to develop their energy industries. Furthermore, the ability of these Arab countries to carry out large-scale infrastructure projects is also a powerful attraction for African states, always in search of rapidly developing. The common religious heritage has also favored the strengthening of ties.

When Western economies went into crisis, some African leaders asked the Gulf monarchies for economic help, and they did so by appealing to their religious ties. The expansion of development aid on the continent also serves to strengthen their reputation among African Muslims, while promoting their own economic interests. As their economic interests in Africa have grown, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar have also expanded their military presence, primarily in the neighboring Horn of Africa.

Indeed, in addition to supporting anti-piracy efforts in Somali waters, they boosted their military capabilities by building their first bases in the Horn of Africa. The trigger element in this case was participation in the war in Yemen, a particularly significant nation in the context of the new global order, in which maritime traffic is strategic and from where maritime traffic to and from the Red Sea, the Suez Canal (and, consequently, the Mediterranean), and the Arabian Sea can be controlled. It is also the Asian guardian of the Bab el Mandeb Strait. In both sections of the strait, between Yemen’s Perim Island and the port of Djibouti, as well as between Yemen’s Hanish Islands and the Eritrean strip of islands, it is less than 10 miles wide. This implies that maritime traffic through the strait can be easily controlled (and/or threatened).

In the case of the Emiratis and the Saudis, despite their substantial differences and oppositions, they have also intensified military cooperation with the aim of playing a leading role in international operations to combat terrorism in the Sahel. In this sense, the Islamic Military Coalition against Terrorism (IMCTC) was launched in 2015 under Saudi patronage. This platform has greatly enhanced military cooperation and intelligence sharing between Gulf monarchies and African states. In this context, Saudi Arabia and the UAE contributed $100 million and $30 million respectively to the multinational G5Sahel force in 2017.

In recent years, the Gulf countries have opened dozens of embassies in sub-Saharan Africa and have intervened diplomatically in African conflicts with the aim of increasing their international prestige. The most recent is Sudan, where once again Saudi Arabia and the UAE support each of the warring factions, not to mention Libya, where the UAE openly supports the de facto government of Cyrenaica.

The perception of the uncertainties and weaknesses of US policies from the continent partly motivated these interventions. With Washington in an unclear position, the Arab monarchies seem determined to find a space. What appears different in the action of these nations is the availability to complete the peace agreements with important economic incentives, while other ‘honest brokers’ have failed, also because they did not have the availability/or the will (or the souk mentality, more openly) as in the case of the 2018 Jeddah Peace Agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea, sponsored by the Saudis and the Emirates and accompanied by investment promises.

There is a line of thought which sees positively that diplomacy is also based on the principle of peace for money. In fact, without funds, in the aforementioned case, peace would have been impossible and that its fragility lies precisely in this condition. In the case of the peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea, in addition to the economic opening to the interests of the Gulf, there is, among other things, the construction of an oil pipeline between the two countries by the UAE and a railway that connects the ‘Ethiopia with the port of Assab in Eritrea. It should also be noted that since 2021, the emirate of Abu Dhabi has been working as a mediator in the dispute between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan over the partition of the Nile River.

In the case of the crisis still afflicting Sudan, when it exploded closer to General Abdel Fattah al Burhan (while the UAE is openly supportive of General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, “Hemeti” commander of the former Janjaweed), Saudi Arabia, together with the USA, he launched a diplomatic initiative by bringing together the representatives of the two opposing groups in Jeddah, even if without results. It also participated in the evacuation of foreign civilians on its ships by disembarking them at its bases on the eastern coast of the Red Sea.

Saudi Arabia

With the ascension of Mohamed bin Salman to crown prince and actually ruler of the country, Saudi politics is undergoing a gradual transformation, not only in foreign policy but also in issues that seemed untouchable, such as individual freedoms and the rights of women and an initial opening to tourism. In the case of sub-Saharan Africa, until recently Saudi Arabia had not had a specific, coherent and long-term projected foreign policy, other than the promotion, dating back to the 1960s, of the Wahabi rite among the Islamic populations of the continent and this with the aim of sabotaging the Nasserian, secular and socialist propaganda. But for about ten years, the instability of Yemen and Sudan, the fragility of Egypt have been the drivers of Riyadh’s new approach and dynamism. In this, profound differences emerge with the approach and perception (and therefore in the modus operandi) of Saudi Arabia, compared to that of its major competitors UAE and Qatar and geographical issues are prevalent.

Against the background of the war in Yemen, currently in a situation of fragile ceasefire, the Horn of Africa region has assumed an exceptional geostrategic relevance for Saudi Arabia, since the countries of this area have become an important element for the security of Riyadh, which has also maintained links of a historical nature with that region. The strategic uncertainties of Washington which, having achieved energy autonomy, has a less strong interest in the events of the region, leave a gap and Saudi Arabia has found itself forced to adopt a different approach in the Horn of ‘Africa (and on the continent) to protect their national interests.

Unlike the UAE and Qatar, Saudi Arabia is geographically close to the Horn and directly overlooks the Red Sea and any instability phenomenon in those areas can impact the security of Riyadh which must act with greater caution. Riyadh sees a link between Yemen and the Horn of Africa and since it launched military operations against the Houthis in March 2015 the importance of the region for Saudi national security is central. Therefore, Saudi Arabia has lobbied the various governments of the Horn countries to forge an alliance and join the anti-Houthi coalition in Yemen. Sudan, Eritrea and Somalia then joined the Saudi Arabian-led military axis, sending contingents of infantry (which lacks Riyadh’s ground force structure) albeit intermittently. Obviously, this contribution has been generously compensated, as in the case of Sudan.

The priority in Saudi regional policy is the resolution of the conflict in Yemen, as this has become an economic and security disaster for Riyadh in recent years. The recent improved contacts with Iran, although still in their infancy, are a reflection of Saudi Arabia’s political will to diplomatically overcome this conflict, since a military solution has become unlikely. But the conflict with the Houtis is not the only source of concern for Saudi Arabia regarding the overall security of the area between the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.

There are flows of irregular migrants, smuggling and drug trafficking, illegal fishing and piracy and Riyadh, in 2016, signed an agreement with Djibouti to build a military base and to strengthen the control of maritime and oil traffic to and from the Red Sea, which however weakened when the UAE took control, not agreed with the Yemeni authorities, of the island of Socotra and subsequently of other islets of that archipelago. Like the UAE, given the same geographical and meteorological situation, Saudi Arabia also aims at massive purchases of land for agricultural use, both in the Horn of Africa and in other parts of the African continent, in light of the expected population growth.

The tool of the Saudi penetration and influence policy is the Saudi Development Fund, a gigantic institution which finances almost everything and which has made over 4 billion euros available for Africa alone (almost half of which, however, goes to Egypt) but the Maghreb states (Morocco and Mauritania) and the Horn of Africa and East Africa stand out which also records significant losses, ultimately representing a political problem for Riyadh’s expansion projects as with financial support and humanitarian aid, Saudi leaders seek to forge political alliances, presenting themselves as reliable guarantors of support for development policy and as generous partners and donors.

In its policy of building an overall security framework, Riyadh is also interested in membership and the creation of multilateral forums. An example of this policy is the Council of Arab and African States Bordering the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden (known as the Red Sea Council). It originated in January 2020 on a Saudi initiative and includes Egypt, Yemen, Jordan, Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti and Somalia. The goal of this association is to improve trade and safety along this waterway, through which approximately 13 percent of world trade flows. The forum has so far failed to achieve significant results, but it serves as a platform for the Saudis to pursue common security interests, cultivate regional loyalties and solidify anti-Iranian ties.

Finally, it should be noted that Saudi Arabia does not enjoy a dominant role as a creator of maritime networks and depends in part on the infrastructure of the UAE and in the meantime pushes hard for the strengthening of its naval forces. However, Riyadh plans to invest more in the logistics sector, especially in the Horn of Africa, with the aim of lightening its dependence on the UAE and also to be able to compete with China in the region, in fact for Beijing the Horn of Africa is a strategic center of the BRI (Belt and Road Initiative), which has a military base in Djibouti and major interests in Kenya.

Qatar

Over the past two decades, Qatar has become a major international player due to its position as the world’s leading producer of liquefied natural gas. Its reserves, the third largest in the world after Russia and Iran, have made it possible for its rapid economic take-off. But Qatar is not satisfied with the status of energy power and from a geopolitical point of view it seeks to emerge as a regional power and above all to escape Saudi hegemony and rivalry with the UAE. It is precisely these parameters, i.e., the search for strategic independence, that Qatar has launched into an unscrupulous foreign policy, dissociating itself as much as possible from Saudi initiatives, as in Yemen, from whose anti-Houti stance Doha emerged in 2017, making public its distance from Saudi Arabia, approaching Turkey (and hosting important military installations or, still being not very hostile towards Iran and developing mediation initiatives such as sending interposition forces to patrol a disputed area between Eritrea and Djibouti, later withdrawn due to the alignment of these two states with Saudi Arabia and against Qatar itself.

In addition, Qatar uses the financial instrument of the Qatar Investment Authority, which together with Qatar Airways, Al Jazeera are important influence drivers, however Qatar’s diplomatic action in Africa, such as the opening of embassies (Qatar has opened more embassies in sub-Saharan Africa in recent years than any other state except Turkey) and the promotion of negotiations collides with the problem of the numerical and qualitative insufficiency of personnel (not yet sufficiently experienced), as in the cases of the negotiations between Eritrea and Sudan, Chad and Sudan, Eritrea and Djibouti (all with poor results also for the Saudi influence which led all these countries to side with Riyadh).

But Somalia (together with Libya) remains one of the pillars of diplomatic action, and not only, of Qatar in Africa. While relations with the Maghreb (Algeria, Morocco and Mauritania) are ancient and consolidated with sub-Saharan Africa, with the notable exceptions of Sudan and Eritrea, they are recent and in the process of further development, primarily with hydrocarbon producing nations such as Nigeria and Congo or solid economic realities like South Africa. In the area of food security, like its neighbors, Qatar is heavily dependent on food imports and has developed large agribusiness programs both in the Horn and in East Africa. As a provider of official development aid, the sub-Saharan African countries from which Qatar has benefited the most are Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Somalia, Sudan, Guinea, Mozambique, Congo, Senegal, Comoros and Djibouti.

Qatar has had a very significant influence on conflicts in Yemen, Syria, Iraq or recently Afghanistan, hosting talks and negotiations. All this has meant that the Qataris have become attractive and, despite a normalization with its regional competitors, the differences remain and can arise again. The Qataris maintain important discrepancies with the Saudis and the Emiratis. One of the main reasons is the rapprochement of the former with political Islam in general and with the Muslim Brotherhood in particular.

The Saudis and UAE, for their part, believe that this group intends to destabilize the established order in the region. In the scenarios shaken by the Arab Spring uprisings, Saudi Arabia and Qatar found themselves supporting opposing or competing factions, and the UAE sided with the Saudis (at least in this one) and the pressure on Qatar increased. Thus, in June 2017 there was a diplomatic crisis: Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Egypt and Jordan severed their diplomatic relations with Qatar, which they accused of interfering in their internal politics and supporting terrorist groups (actually Qatar’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood is anything but ideological but instrumental, given the objective of subverting the models of these states, all close to Riyadh).

The closure of the borders and the restrictions on air and sea traffic have caused a crisis in Qatar which has also affected the food supply. Iran and Turkey have supported Qatar, creating a worrying system of alliances and hostilities that has led to an imbalance in the region’s already complicated set-up. Thus, Qatar began to build a progressive rapprochement with Turkey, one of the main contestants of Saudi Arabia’s attempts to affirm its regional leadership, and with Iran, (at the time) the main enemy of the Saudis. This rivalry has transferred to the neighboring Horn of Africa; Sudan, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somaliland have been closer to Saudi Arabia and the UAE during the 2017 diplomatic crisis, while Somalia has adopted a neutral stance not to put its good economic relations with Qatar and Turkey are in danger. During the four years that the blockade has been in place, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have obtained lukewarm support in African countries (certainly not in proportion to the aid given by Riyadh and Dubai) and the choice of neutrality has been seen as a support of made of Qatar.

In the highly sensitive Somalia, the rivalry between Qatar and the UAE negatively impacted the already difficult relations between Mogadishu and the autonomous regions of Somaliland and Puntland due to the growing economic and military presence of the UAE in those de facto independent regions, and which Somalia is trying to reabsorb in the federal structure. In any case, the rapprochement between Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE in January 2021, which triggered the end of the blockade and the return to diplomatic relations, has allowed African countries to improve relations with both sides and rescue them from the unpleasant situation of having to choose between two (actually) lines of funding (as was the case in Morocco).

United Arab Emirates

The will to develop a real African policy was initiated by the UAE after the 2008 financial crisis, decided to refocus your international investment strategy. The push has been such that several Western companies, already operating in Dubai, have reconfirmed it as a base from which to operate in African countries due to the advantageous tax conditions and direct connections with the main African capitals. Furthermore, Dubai has attracted a growing number of African businessmen, who have chosen this emirate as their base for investment. The number of African companies registered with the Dubai Chamber of Commerce and Investments has increased exponentially in the last decade and the UAE is firmly betting on Angola, a fast-growing country as a hub for continental expansion.

However, alongside economic interests, the UAE has important security drivers, such as the fight against religious extremism in particular that carried out by the Muslim Brotherhood galaxy. The widespread instability in the Middle East – the rise of the Islamic State, the collapse of Libya, the conflict in Syria, the never-ending crisis of Lebanon and Iraq, the ever-shaky Egypt and the growing influence of Iran (and the related Yemeni problems) has sparked paranoid fears in Gulf nation leaderships, but the threat from groups affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, it is considered existential, also have a presence, albeit limited, within the Emirates. Its rise alarmed UAE leaders, especially as conflicts in the Arab world seemed increasingly intertwined, with events in one country spilling over into others.

The UAE has implemented with many African countries what some have called its “Egyptian model” diplomatic, military and financial support to stable political actors who are seen as the most capable of containing Islamist movements. This is how it acted, as well as in Egypt, in Yemen and Sudan. In this sense, the UAE conditions its development aid and investments on the African authorities showing support for their strategic orientations, i.e. adhering to their agenda against political Islamism.

The UAE is the fourth largest investor country on the African continent globally — after China, the United States and France — and the largest overall among the Gulf states. Between 2016 and 2021, the UAE invested approximately $1.2 billion in sub-Saharan Africa and is among the continent’s top ten importers of goods and commodities. Non-oil trade between the UAE and Africa is estimated at $25 billion a year. In the last fifteen years the volume of trade between the UAE and the African continent of products other than hydrocarbons has grown by 700 percent.

Investments from the Emirates are directed towards telecommunications, energy, mining (gold and coltan) agriculture, port infrastructures, where the presence of Dubai Ports (DP) stands out, currently managing some of the most important port terminals in sub-Saharan Africa: Dakar (Senegal), Berbera (Somalia), Maputo (Mozambique) and Luanda (Angola), Bosaso (Puntland [Somalia). In Djibouti, DP also managed the port of Doraleh until the contract was terminated by the local government in 2018. DP has also obtained a concession for the construction of a logistics center in Kigali (Rwanda) In addition, new projects are being negotiated in Sudan and Madagascar For its part, Abu Dhabi Ports manages the port of Kamsar (Guinea) Port investments and agricultural land acquisition are part of the food security strategy, as the UAE imports 90 percent of domestic consumption.

As with Saudi Arabia, the conflict in Yemen has made the Horn of Africa region the main strategic area where the UAE has deployed its own military mission, whose performance has solidified the myth (much mythologized, indeed, even due to the poor results obtained by the Saudi forces) of the ‘little Sparta of the Middle East’. At the outset of the conflict in Yemen, the UAE was alarmed by the advance of Houthi rebels near the Bab Al Mandeb Strait, as the possibility arose that an Iranian allied group would control that vital trading point of the Emirates. But in addition to the aforementioned Angola, the UAE is also extending its presence in West Africa, and in the Sahel: in Senegal and Guinea, as already mentioned, they manage port infrastructures in Dakar or Kamsar; in Morocco, Mali, Mauritania, Chad and Burkina Faso investments were made in civil and military infrastructure. In their strategy to fight Islamist forces and financing of the G5 Sahel and there are signs for further expansion and penetrations in coastal areas of Atlantic Africa.

Conclusions

The expansion of existing rivalries in the Gulf to the Horn of Africa, where there are already many, is not a good thing and risks spreading to the rest of the continent, as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar progressively consolidate their presence. In this scenario, the rivalries between these actors will be more heated in the belt that goes from Egypt to the Horn of Africa, where the control of the security and navigation of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden is fundamental internal stability, commercial interests and their food security, and this is only possible if there is a presence on both sides.

Enrico Magnani, PhD, is a retired UN official and expert in military history and international politico-military affairs.