Capitalism and the West have long been inseparable. In order to understand this special relationship a little better, we recently had a fascinating discussion with Jayant Bhandari whose area of expertise is investment in various sectors of industry, especially natural resources. Mr. Bhandari brings an important blend of experience and wisdom that veers past the usual nostrums that we are often forced to hear. He has published widely on economics, investment, culture and the question of liberty.

Mr. Bhandari also organizes and runs, “Capitalism & Morality,” an annual seminar on freedom. Further information about his work may be found on his website.

The Postil (TP): Your project of “Capitalism & Morality” is a very interesting one. Could you please give us a description of it, and what led you to start it?

Jayant Bhandari (JB): My first flight and trip outside India was to the UK in 1991. Though I often felt hungry while living there, those 20 months were the best of my life. I experienced liberty and respect, witnessing the harmony with which people worked. From my perspective, it was a well-oiled machine. People walked around unmolested, unafraid of those in power. The constant dynamic of the oppressor-subservient relationship I was accustomed to in India was nowhere to be seen among the native English. People did their work without asserting power or asking for bribes.

People in the UK were sophisticated and knowledgeable about their work areas, unlike in India, where people didn’t pursue further learning or reading after leaving university. In India, education was viewed not as a means to learn skills or provide services but as a tool to acquire wealth and power. Anyone with even a slight amount of power was bound to flaunt and abuse it.

In the UK, people openly and freely engaged in conversations without the pressure of being proven correct. They sought truth, a concept alien to me, as discussions as matches to be won. There, I began to grasp the meaning of “truth” for the first time.

I was surrounded by immense prosperity and well-being, shocking me for decades. Could all that wealth indeed be possible? I had only a superficial glimpse of the UK before I moved there. With time, I would discover the reservoir of virtues inherent in Western civilization beneath the visible surface.

In the society where I grew up, moral values held no significance. People could not distinguish between sins and virtues, and the larger society admired individuals who engaged in criminal activities and evaded consequences.

Without foundations in objectivity, reason, and morality, India was so dysfunctional or non-functional that I often say that any Indian organization with two people has one person too many. Everything was a show-off, with “might is right” as the operating principle.

I was often amazed at how the UK worked. The authorities were not predatory; weak, disabled, or older people were respected and helped rather than preyed upon. Even children and beggars were treated with respect. I say “even” because in India, the weaker you are, the worse you are treated. Disabled and weak people, widows, orphan girls, and boys were labeled as such and exploited without guilt or shame.

In the UK, men and women were respectful to each other. In India, “happy smiley families” is cynically used to describe families that maintain a façade of niceness while being bloodthirsty. Having grown up in this environment, I was so accustomed to this hypocrisy that I didn’t consider families could be different in the West.

It took me a couple of decades living in the West to realize that families could have decent, happy, and mutually loving relationships. The realization that love could be anything other than physical marked a paradigm shift for me.

My stay in the UK exposed me to the essence of civilization or at least set me on a path to a deeper understanding. It made me aware of the humanistic values that must underpin any civilization. I was awed by the honesty, integrity, honor, fairness, and empathy I witnessed.

I was trusted by people in the West, quite in contrast to India, where no one trusted anyone. In India, trusting someone was seen as foolish, and others would readily label you as such if you made that mistake.

Later, for work and to learn, I traveled extensively worldwide. I have lived in 7-8 countries and visited a hundred. I was driven to understand what distinguished prosperous societies from those in wretched conditions. I extensively researched this topic, delving into a wide range of literature, including new-age books that erroneously claim that poor people are happy even in their drudgery—despite such claims, India consistently ranks as one of the most stressed countries in the world.

I have realized that what the West possesses is unique, something distinct from the rest of the world: a culture of honor and reason intertwined with Christianity. Westerners possess a unique ability to remain rooted in truth and utilize it as a fulcrum to assess facts. Many who grow up within this system often assume their values are universal. However, the truth is far from it; much of the world sees no issue in being envious and covetous. Sins proliferate in their hearts, while virtues remain elusive to them.

In my seminar, I aim to underscore the greatness of Western civilization, the only civilization I have known and come to admire. Capitalism, the economic branch of civilization, is often defined overly simply, mechanistically, and linearly. However, capitalism requires a society with a solid moral foundation, as I have nuanced so far. Ethical values must be instilled and internalized by individuals and integrated into our social and economic relationships.

TP: As you know, “capitalism” and “morality” are often seen as being incompatible categories. How do you understand “capitalism?”

JB: As I have mentioned, morality, reason, and honor are inherent in the concept of capitalism. However, many people perceive capitalism as a system driven by unrestrained greed, akin to the Wild West, where certain individuals have the right to exploit the underprivileged and the weak. For these individuals, money devoid of values is all that matters. This distorted version of capitalism is often termed “crony capitalism,” which is, in essence, an anti-concept. It unfairly tarnishes the reputation of capitalism, especially in the minds of those who do not delve deeply into the matter.

The very term “crony capitalism” is deceptive, juxtaposed with the seemingly benign term “socialism.”

Most people fail to delve deeply enough to recognize how their base instincts are exploited for manipulation. Our emotions and primal instincts are deeply ingrained, exerting immense pressure that renders our reasoning capacity malleable and highly vulnerable. Constantly seeking rationalizations, our animalistic instincts and primal desires yearn for expression by any means necessary. Invariably, emotions prevail over reason. Nothing is more cathartic than discovering a gap, a loophole—using the language of software—in our civilizational values to indulge our sinful nature.”

People are infused with certain emotions through propaganda, marketing, sloganeering, and soundbites, all disguised as virtuous cover-ups and rationalizations for their envy and covetousness. This serves as the foundation for their disdain towards capitalism. This hypocritical approach is even more insidious than raw envy because the believer becomes entrenched in his narrative, preventing them from ever examining their subconscious.

Some individuals have turned their sugar-coated sinful nature into a profession. These are the so-called do-gooders, the modern-day Robin Hoods who believe they know better how others should live or use their money. Scratch beneath their veneer of virtuosity, and you’ll find a lust for power and a desperate desire to control other people’s money.

There is a reason why our base desires should be channeled appropriately or restrained from the outset. Sins and virtues are not inherent in the universal firmament; they require continual reminders and conscious awareness to ensure we remain vigilant in recognizing them. We must be reminded regularly of the actions we should adamantly refuse to engage in. Otherwise, we risk falling into rationalizations, as often seen in the behavior of so-called do-gooders.

In essence, those who blame capitalism—within the detailed definition I provided earlier—for being regressive and sinful, ironically, often project their own character flaws onto others.

The question remains: Do systems of exploitation, abuse of power, and sadism exist in the world? Sadly, this is how most of the world is run, reflecting our original, natural state of existence. In at least half of the world—Africa, Latin America, the Indian subcontinent—oppression is so rampant and the law of the jungle so prevalent that those who grew up there cannot conceive of a moral system. This included me. This worldview handicapped me from understanding the meanings of certain words and concepts. As I mentioned earlier, I had a skewed understanding of the word “truth.” Similarly, before arriving in the UK, I believed that “socialism” meant the power to abuse and exploit others.”

Virtually all of the oppressed world claims to be socialist or communist, with their leaders often portraying themselves as do-gooders. However, the only places where exploitation and abuses are minimized are the capitalist nations of the West and East Asian countries like Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and, increasingly, China. These countries have adopted institutions and social behaviorism modeled after the West, leading to their relative stability and prosperity.

If a society lacks morality, the notion that an external structure like a socialistic government can enforce morality is logically fallacious. Governments, at best, arise from within their people, although they may manifest in psychopathic forms with far less accountability.

While some individuals mistakenly believe that the capitalist system offers unrestricted freedom, this notion is fundamentally flawed. Actions that curtail the liberties of others through fraud, oppression, or theft directly contradict the principles of the free market. To truly grasp the concept of the free market, one must understand its inherent complexity, wherein individual actions are intricately interwoven with transactions among people.

The essence of the free market lies in its universality—it can only truly be free if it ensures freedom for everyone.

As a corollary, the free market can exist only among morally evolved people. The degree to which people are amoral or immoral creates fissures for psychopaths to emerge into positions of power and tyrannical governments to emerge. Expecting such socialists or communists to do anything except predation is a fool’s errand.

It’s worth reflecting on the cultural evolution ignited in England during the Industrial Revolution. This era ushered in a surge of prosperity that left the rest of Europe bewildered. While the inventions existing for centuries played a role, the true catalyst lay in the invisible workings of capitalism and its underlying social and moral values. The English harnessed these inventions for societal betterment, guided by principles of fairness, respect for contracts, and honor. These values served as the bedrock that harmonized society’s intricate workings, though it’s important to acknowledge the generations of turmoil that also ensued from this transformative period.

Capitalism transcends mere economics; it fosters a symbiotic relationship with meritocracy, honor, and other human virtues. Through this synergy, capitalism facilitates a continuous refinement of society, as evidenced by Europe’s historical evolution over time. Even those who fail to understand or respect moral values must act them out in such a system.

Capitalism refines and inculcates moral values in society.

In societies lacking moral evolution, kleptocracy and a dog-eat-dog mentality prevail. Some argue for enforced socialist structures in such contexts to hinder wretchedness, predation, and degradation. This is very idealistic and detached from reality. Unfortunately, there is no easy remedy for morally backward societies, condemning them to a wretched existence. Whatever you do, their economic and social relationships and law and order would mirror the moral impoverishment of such societies. Moreover, imposing socialism would exacerbate the situation, providing opportunities for even worse psychopaths to ascend to power, as evidenced by the post-colonial experiences of the Third World countries. Such a system would institutionalize predation and foster citizen apathy and fatalism due to the lack of incentives for self-improvement.

The only hope for morally impoverished societies lies in establishing a benevolent dictatorship supported by an army of ethically strong bureaucrats. This is only possible through colonization. The British, French, Germans, and Portuguese should never have left sub-Saharan Africa, India, and elsewhere. Despite centuries of efforts by colonizers and Christian missionaries to awaken these societies, success was limited. As it stands today, the only future I see is that the Third World countries will fall apart and devolve into Taliban-like systems, which will be an improvement on their current so-called socialism. Over centuries and millennia, some may organically evolve into civilizations, but the prospects are dim for most.

Not too long ago, I advocated for the end of drug prohibition, the legalization of prostitution, and the open expression of one’s sexuality. However, witnessing the consequences firsthand in places like Vancouver, where I have spent much time, has led me to reconsider. With the increasing legalization of drugs, crime has surged, and more individuals have become unhinged and dependent on society. The availability of drugs has made it easier for them to be pushed onto vulnerable individuals, including children.

One might argue that within capitalism, as long as transactions are conducted fairly and with consent, the availability of drugs, prostitution, and other vices should not be restricted. However, we must acknowledge that even seemingly victimless sins can have detrimental effects on society as a whole. Prostitution often breaks apart families, while drug use fosters dependence on society’s resources.

A crucial aspect of capitalism is the existence of civil society, along with institutions of liberty and social opprobrium associated with unethical behavior. Those who envision capitalism as a lawless, do-as-you-please environment have not fully grasped its complexities.

TP: And “morality” first necessitates transcendence; in other words, where do you base “morality” that can then work alongside capitalism?

JB: As I mentioned earlier, morality is intrinsic to capitalism. We are all driven by base, primal, animalistic desires that often override reason unless tempered by moral consciousness. Discipline and self-control are essential precursors, necessary to restrain and direct our base desires toward morally right actions rather than succumbing to emotionally attractive impulses.

The emergence of moral consciousness marks the beginning of civilization. Europe is a prime example, undergoing millennia-long processes that intertwined Greco-Roman philosophy, a culture of honor, and Christianity. This amalgamation was a transcendence, a pivotal shift from mere animals to fully realized human beings. Similarly, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean societies developed honor cultures that enabled them to adopt positive aspects of European civilization.

However, much of the world remains oblivious to these civilizational values and instead indulges in hedonism and materialism, relegating themselves to savagery and barbarism.

TP: Since “Wokeism” is also a “moral” project, there is also therefore “woke capitalism,” where all the mega-corporations push progressivism as their “morality.” How are we to separate “Woke morality” from your own project?

JB: I don’t see it that way. “Woke capitalism” is an oxymoron. Values are essential for accumulating both philosophical and financial capital. Wokeism has non-values of hedonism and virtue signaling. It has fantastic similarities with Third World non-cultures. It embodies a regression, a departure from civilizational constraints towards a feral existence.

Wokeism is repulsive and fundamentally anti-civilization. It is inherently amoral and leads inevitably toward savagery and barbarism. Woke people might look cute and admirable only within the confines of a civilized and prosperous society that bears the costs and burdens of their ideology.

There is a reason why all religions disdain hedonism. Initially, wokeism appears innocuous, even appealing, but left unchecked, it becomes increasingly perverse. Like termites, it will eat away the civilizational innards of the West.

Wokes are often associated with leftist ideologies. It’s worth considering what Stalin or Mao would have done with them—they likely would have been among the first sent to the Gulag.

At first glance, wokes may appear affable and non-threatening. They might engage in peaceful protests or civil disobedience, occasionally inconveniencing others by blocking roads. However, they don’t pose direct harm like terrorists. They seem to care about poor people and the environment. They might smoke a joint and then immerse themselves in a pleasant feeling. They express their sexuality freely, unrestrained from societal expectations.

Wokes have employed political correctness and cancel culture to shut out free speech and manipulate language to neutralize social opprobrium and effectively alter societal standards, all to steer society into following their feral ways.

I trace the emergence of wokeism to the 1960s, particularly when the hippies began traveling to India. The Beatles, in particular, played a significant role in popularizing India as a mystical land imbued with spirituality. For visitors coming from disciplined societies with strong honor codes and civilizational constraints, the Indian experience was cathartic. India is chaotic and has no civilizational boundaries. The visitors to India partook in drugs and an ecology of no dos and don’ts. The money they brought from the West went far, further enhancing their sense of freedom and euphoria.

These visitors did not engage in societal life in India, thus avoiding exposure to the less glamorous aspects of paganism and moral relativity. Their experience was akin to visiting a pub on a Friday evening and being surprised by the friendliness of the people there—without experiencing the less pleasant aspects of those same individuals. It was a selective encounter with freedom and liberation, divorced from the broader context of societal realities.

Catharsis is not spirituality.

For an Indian, however privileged or well-placed, India is an unmitigated hellhole—a cesspool of corruption, savagery, and barbarism characterized by the absence of honor, values, civilization, and, ironically, freedom. This grim reality starkly contrasts the romanticized view of India experienced by the hippies. The consequences of wokeism, as seen through the lens of Indian society, reveal a disturbing truth. I recommend watching a documentary, The Gods of New Age, to gain an insight into the insidious effect of seemingly benign belief systems.

Over time, woke beliefs have permeated deeply and widely in society. Today, the notion of diversity, inclusion, and equity (DIE) has become ubiquitous. It’s no longer confined to mega-corporations; even smaller companies and family gatherings must pay lip service to these principles under the threat of cancellation. Banks and other service providers may refuse to cater to individuals whose views they find objectionable. This is their way of marketing themselves as chivalrous to get more clients and business. This money-centeredness, which confuses everyone, including themselves, in the garb of virtue-signaling, is not capitalism.

I envision a capitalist as akin to the heroes depicted in Ayn Rand’s books—willing to shrug and risk losing everything for their values.

Wokeism, if seen for what it truly is, emerges as fundamentally anti-meritocratic. This ideology is eroding our corporations, even impacting safety-critical industries like Boeing. It’s concerning to ponder the compromised state of their organization, where individuals lacking merit may have risen to top positions, and subcontracting decisions may prioritize factors other than quality.

Wokeism and the anti-meritocratic order it engenders will prove to be the death kneel of Western civilization. As termites do, it will eat away the innards of the West.

TP: Many countries deploy capitalism in differing ways; for example, China’s use of capitalism has led to different results than, say, India where capitalism seems to have only created greater chaos and a deeper divide between the rich and the poor. How would you explain this dynamic? Does this mean that capitalism is not good for all nation-states?

JB: I am a frequent visitor to India and China. Chinese banks open until late in the day and even on holidays. Chinese want my business. If they don’t have what I want, they will find a way to provide it. There is a huge emphasis on children’s education, their extra-curricular activities, and developing them into well-rounded human beings. While I may not always agree with the methods employed, I admire the determination and willpower driving China’s rapid economic growth and its aspirations toward becoming an educated and well-rounded society.

During my visits spanning the last two decades, I’ve witnessed remarkable progress in China, both economically and culturally. The country has become notably more prosperous, sophisticated, and environmentally conscious, leading to greater well-being and happiness among its people. Once marred by pollution and environmental degradation, Chinese cities have radically transformed. Rivers once littered with animal carcasses are now actively maintained, and the air quality has significantly improved.

The Chinese are remarkably eager to learn from foreigners, often approaching them to practice English and showing a keen interest in emulating aspects of Western, Japanese, and Korean cultures. Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore, whom I consider the greatest statesman of the last century, was pivotal in guiding Deng Xiaoping in establishing effective systems and institutions. This influence is evident in their public transportation system, which resembles Singapore’s. Today, traversing the highways of China can evoke the feeling of being in the USA or Canada, a testament to their capacity for rapid adaptation and transformation.

Over time, I’ve noticed significant changes in Chinese society. There’s been a noticeable decline in behaviors like spitting on the streets, with people increasingly adhering to norms like lining up. Contrary to the narrative often portrayed by the international media, I’ve witnessed instances of Chinese citizens actively fighting for their rights with police and government authorities. While openly challenging the legitimacy of the CCP may be risky, it’s essential to recognize that no country is perfect, and comparisons should not be based on an idealized notion of perfection. Although political conversations are not openly conducted, it’s worth questioning whether widespread political activism, as seen in the West, is necessary in a society where many individuals may lack awareness of political developments.

During my visits to China, I’ve witnessed firsthand the flourishing free-market economy. Everything seems readily available, from abundant fruit and groceries to a wide range of goods and services. What’s more striking is the remarkable improvement in quality across the board compared to my visits over the past years. It’s evident that people take pride in their work and are committed to providing high-quality services, reflecting the dynamism and vitality of China’s economy.

While China lacks some of the philosophical and moral values of the West, its day-to-day operations reflect a strong adherence to capitalism, sometimes even surpassing that of the West. It’s conceivable that China will gradually absorb more Western values, aided by the corrective interactions inherent in capitalist systems.

India does not follow capitalism. It is a wretched hellhole, wallowing in poverty, sadism, mysticism, irrationality, depravities, exploitation, and degradation. I would not have used these words had I seen India improve. It continues to worsen with time, with its institutions now hallowed out and with utterly corrupt and, worse, braindead people manning those.

The Indian mind is ossifying. It is becoming increasingly xenophobic, anti-minorities, parochial, mystical, irrational, and uncivilized. India is dominant in the list of the world’s most polluted cities. Ironically, it became polluted even before industrialization started.

Indians don’t set high standards for themselves and ridicule those who do. Indians find shortcuts at the cost of quality and safety. In an economic transaction, they think in terms of transferring money from your pocket to theirs—any value they create is incidental.

The concept of philosophy and ideas is missing in India. If you discuss ideas, people laugh at you. People are incredibly money-minded and materialistic. When they grow more prosperous, unlike in China, they become even less compassionate and more sadistic. When given higher positions, the lower-caste people exploit in ways that the higher-caste couldn’t even dream about.

India does not have capitalism. I call its system chaos-ism or feral-ism. So dysfunctional it is that even socialism would be a vast improvement. Alas, India is continuously getting worse. Society is disintegrating, and the institutions that the British left behind have been hallowed out. India will continue to regress towards its pre-colonial days.

I have no issue with a divide between the rich and poor as long as people are not denied opportunities and the institutions treat them fairly, which includes letting them go hungry if they refuse to pull their weight. Ironically, when poor people get into a victim mentality, their low position in life solidifies. I have yet to meet a German, a Japanese, or a Japanese-American who complains about what the USA did to them during World War II. Winners move on in life, which is why Germany and Japan have become one of the most prosperous nations in the world and Japanese-Americans among the most assimilated people in the US society.

Unless wealth disparity exists within a legitimate institutional framework that is not predicated on class, caste, racism, sexism, or affirmative policies that perpetuate new forms of bigotry, there is no incentive for individuals to strive for improvement. The implementation of redistribution and welfare systems in the West has led to a decline in values such as self-reliance, honor, and the pursuit of excellence. Instead of fostering a culture of self-improvement and aspiring to higher values, reliance on welfare programs contributes to a decaying sense of individual agency.

At the heart of capitalism lies morality, which gives rise to institutions built on principles of liberty, justice, and contractual integrity. Societies lacking in ethics see the proliferation of tyrannical and predatory systems. Attempts to enforce top-down values in such societies backfire as institutions adapt to underlying moral deficiencies, exacerbating societal issues.

In essence, artificially enforced institutions can become distorted and work against their intended purpose, leading to outcomes that contradict their original design. While this perspective may seem unconventional to modern Western sensibilities, many parts of the world find structures resembling the Taliban’s governance to be natural, sustainable, and equitable. India’s trajectory reflects a move towards such a model.

The key lies in fostering a moral society where capitalism can organically emerge. My seminars have reflected this, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing morality in societal development efforts.

TP: What stage are we at with capitalism in North America; and here perhaps you could contrast Canada and the USA?

JB: In both Canada and the USA, the pillars of morality, social opprobrium against bad behavior, and the integrity of law and order have faced continuous erosion. Canada, historically ahead of the USA in terms of welfare and liberal policies, has seen these initiatives stealthily undermine the foundations of society, akin to the gradual but unseen until-too-late destruction wrought by termites. Despite my deep affection for both countries and their vibrant, compassionate populations, the undeniable reality is that our societal foundations have decayed.

I find it challenging to pinpoint the singular root cause behind the erosion of Western societal values. Could it be feminism or the misguided acceptance of compassion and tolerance as unassailable virtues? Or is a multi-ethnic society, like the USA, destined to decay, which also passed on its political correctness to the rest of the West? The emphasis on multiculturalism, with its portrayal of every culture as equally valid, may have inadvertently fostered moral relativism akin to the pitfalls of paganism and polytheism. Alternatively, the post-World War II guilt, possibly fueled by Christianity, could have played a role. Why have honor and individual responsibility slipped away as social values? Or was it the misinterpretation of liberty, as exemplified by the hippie movement and its association with India’s feral culture, easy access to drugs, promiscuity, and the facilitation of public protests, that catalyzed this metastasis in the West?

I find myself pondering why countries like Japan, Korea, Singapore, and Hong Kong, despite extensive adoption of Western practices, have managed to sustain societal improvement without succumbing to the decay observed since in the West. East Asia’s survival involves staying ethnically homogenous. Homogeneity does not allow any subgroup to feel victimized and ask for special privileges, compromising meritocracy. Additionally, these societies’ prevalent sense of shame ensures that social opprobrium effectively reinforces societal norms, and they do not feel guilty about ancestral actions. While East Asian nations afford many liberties similar to the West, they strictly prohibit drugs and view woke ideologies unfavorably, and their overt promotion is often met with legal repercussions.

Some believe societal awakening will occur in the West as conditions deteriorate. However, history suggests societies that worsen because of moral compromises adapt to those circumstances rather than mobilize for change. With weakening objectivity and fraying anchoring to truth, analogous to the proverbial frog in a boiling pot, we acclimate to progressively deteriorating conditions. The West was fortunate to inherit foundational principles such as honor, Greco-Roman philosophy and reason, and Christianity. Yet, once lost, the reconstruction of these values could require a lengthy cycle spanning millennia, potentially accompanied by violence, backlash, and collateral damage. Those who grew up in a society with a moral compass think that it exists in nature. It does not, and discovering it is virtually impossible.

Given these considerations, the future outlook for Canada and the USA is bleak.

TP: In your moral approach to capitalism, how do you understand debt and the banking system in general?

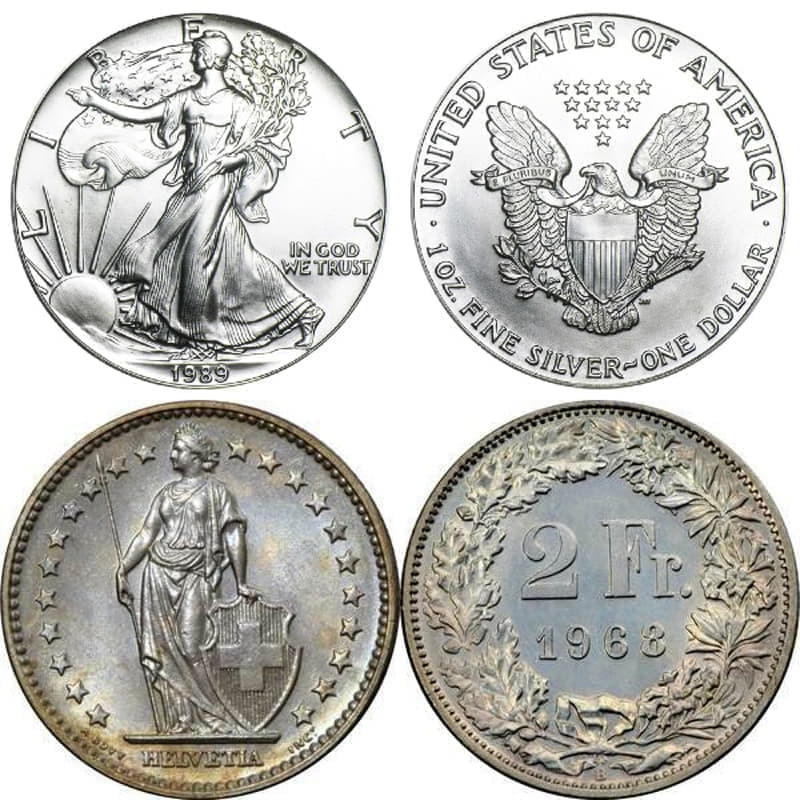

JB: Our society has regressed to a state more degraded than even that of cavemen. We have no money. Erroneously, we consider fiat currency to be money, which hypocritically promises to pay us a clone of the same paper.

Fiat currency, lacking defined backing, means its perceived value depends on government diktats and its ever-changing mood. The government can acquire goods and services by printing new currency, essentially implementing the most fraudulent tax possible, disproportionately harming the poor. This system also imposes substantial unnecessary risk and uncertainty on entrepreneurs, especially regarding long-term planning.

The result is boom-and-bust cycles that the government creates and then tries to dampen or avoid, keeping the pressure down until it can no longer be maintained, as happened in 2008 and as we are currently experiencing with increased nominal interest rates.

Despite being the top currency in the world, the US dollar has lost over 95% of its value over the last century. The real interest rate people get on their cash is negative, even today when the nominal rate is around 5%. Consequently, individuals are compelled to speculate and take risks they don’t fully comprehend to preserve their wealth.

Desperate for yield in a negative-yielding fiat currency system, savers have no choice but to chase investments they don’t understand in hopes of protecting their assets. This desperation creates an opening for scammers to exploit.

You seriously harm society by enriching and empowering crooks and scammers.

Some people chase properties, which are depreciating assets or, at best, non-yielding, although those who have bought properties over the last few decades might not perceive them that way. This situation results in a lot of housing being unoccupied, collecting dust, and succumbing to mold, while for millions, housing remains unaffordable.

There were Keynesians who believed that you could create wealth by breaking someone’s window or even by digging a hole and filling it up. Now, we have an advanced version of these, called MMT economists, who believe that the government’s printing of money creates value and generates no inflation. Those in the government love these MMT quacks.

Fiat currency also imposes a moral hazard on the individual.

The abstract nature of fiat currency fosters a speculative mindset, promoting a focus on money-making without regard for value creation. Ironically, the financial sector is one of the most “valuable” activities in economic terms in the USA. Yet, it so often detracts value from other industries, resulting in significant frictional costs and diverting talented individuals from roles beneficial to society. Many of our brightest mathematicians and physicists find themselves working in the stock market.

Citizens are led to believe that wealth creation lies in trading on the stock exchange, and they often engage in hectic day-trading sessions.

Fiat money fosters a mindset within government circles that money grows on trees. Career bureaucrats and demagogues frequently lack real-life experience, and even if they do possess it, they often have incentives to disregard it due to their positions’ lack of accountability. This environment nurtures a god-like image of themselves as they wield billions of other people’s money or freely printable fiat currency.

Recipients of welfare money, often not too rational or honorable, convince themselves that money is there for the taking, with no cost or burden on others involved. This mentality leads to a deep and widespread decay in moral values. It also fosters the irrational belief that one can improve one’s life simply by printing money rather than through hard work. This incentivizes irrational behavior and promotes a belief in magic.

Without the capability to print money, governments would not have initiated so many wars, nor would we have created a massive population reliant on welfare payments. In the West, we have skewed the balance to such an extent that if welfare recipients are not outright the majority, they hold a significant swing vote. We find ourselves trapped in a vicious cycle.

In short, the harm caused by fiat currency is profound, extensive, and multifaceted.

TP: Closely tied to capitalism is the culture of consumerism where the economy becomes fetishized. Do you see this as a problem?

JB: Although often misunderstood, capitalism has nothing to do with consumerism and materialism. If anything, capitalism encourages thrift. For instance, the owner of IKEA drove a mid-sized car. Despite being one of the wealthiest people in the world, Warren Buffet still resides in the same house he moved into when he was relatively poor.

People who accumulate wealth through productive endeavors do not use it for ostentatious purposes. When a wealthy person was looking for a vehicle in Vancouver, I suggested a Mercedes SUV. It is safe, gives a good pickup, and beats the starting traffic at the intersection lights. He responded that he would be too embarrassed to drive such a car.

The trouble arises when people discover ways to make money easily through financial games and welfare checks, which the fiat currency encourages. For these individuals, money flows like water, appearing easy and free.

The most ostentatious, materialistic, and consumerist societies are not capitalist but rather socialist, as are those in the feral Third World. Those who have bothered to read socialist literature realize it is fixated on money and how to redistribute it.

Materialism is a state of mind resulting from a lack of spiritual interests. Materialists are hedonistic, believing that life revolves around seeking pleasure. Even worse are the money-minded individuals who obsessively collect wealth by any means necessary. Ironically, these people fail to get lasting pleasure, money, or peace. In rare cases, when they acquire such, they fail to find fulfillment.

Materialism proves to be an unsatisfying pursuit, often leaving adherents financially impoverished. Hedonists, constantly chasing temporary highs, struggle to find enduring happiness, perpetually seeking the next thrill. Similarly, those solely focused on accumulating wealth find that money cannot provide lasting security or contentment. Such is the nature of life: external sources of fulfillment are fleeting and transient at best.

TP: There is a capitalist Left and a capitalist Right. How do we distinguish the two? Why is one better than the other?

JB: Capitalists lean towards conservative and libertarian ideologies, valuing solid communities and individual autonomy. Capitalism itself fosters the weaving and maintenance of moral fabric, as individuals learn to engage in transactions without relying on government intervention. A capitalist system establishes invisible moral boundaries, guiding individuals to align their behavior with ethical values. Even those who may not naturally incline towards moral living are influenced to do so by this invisible force. Capitalism enforces a social stigma against unethical behavior.

Upon arriving in the UK for the first time, I was astonished by the cooperative and helpful nature of the people, their aversion to backstabbing, and their willingness to work together. It was a revelation that took me years to appreciate fully.

However, as Western societies increasingly lean towards the left and the regulatory and welfare state has expanded, the incentive for moral behavior has seriously diminished. The government has increasingly become the nanny of people and the husband of women. As a result, society, churches, and temples have mattered less and less, weakening social opprobrium. Moral hazards have emerged as individuals rely on the government for future savings and healthcare needs.

There is no left capitalism. There is only one kind of capitalism, and it indeed has a symbiotic relationship with spiritual and conservative values. You might call it right capitalism, but “right” would be superfluous.”

TP: Does capitalism have a limit? Or is it limitless in its expanse?

JB: Human fallibility and egotism necessitate a robust framework of rules and institutions to maintain a functional society. Contracts must be upheld, justice must be administered, and an external authority is needed if voluntary compliance is lacking.

Capitalism has a symbiotic relationship with morality. To the degree a society lacks values, its deficiencies will reflect in bigger governments and psychopaths in power. If we cannot monitor our behavior, something has to emerge to do so. A morally weak society will have a big government, and alas, a big government will create an ethically weak society.

I am no big fan of the state because it lacks competition and accountability, making everything slow, expensive, often convoluted, and even corrupt.

We cannot go back in time to experience how Europeans ran their countries or when the USA had no income tax, but we can still visit minimal states like Singapore that keep the government small and tight. Eventually, we should work towards minimizing the state and aiming for a no-state situation with maximum competition and accountability. However, a force to keep the state small can only come from a morally improving society.

Prioritizing the development of moral values is crucial. Christian missionaries recognized this, emphasizing the importance of moral awakening in sustaining institutions.

TP: What is the role of the nation-state in relation to capitalism?

JB: The nations of Europe emerged from a tumultuous period marked by decades of wars in the middle of the last millennium. They were organic products shaped by their societies’ desires and social and ethical values, forged through churning, massive violence, and continuous conflict. It’s understandable why they, as nation-states, sought to protect their values from external aggression.

However, Western nations transitioned over time into welfare states, eroding their civilization and core values. They opened their borders without regard for their cultural heritage, diluting the essence of their existence. Trudeau’s characterization of Canada as a post-national state epitomizes this trend.

The state has usurped the roles of local communities, religious institutions, and even husbands within families. Consequently, our communities, families, and civic life have significantly weakened. The state takes away half of your earnings through taxes and interferes in every aspect of your life. Despite this, policing has deteriorated, and crime and drug addiction have risen. Seeking justice is not easy. Doug Casey argues that the judiciary and policing are too essential to be left to unaccountable bureaucrats and demagogue politicians.

The issue with the nation-state, especially within a democratic framework, lies in its inherent incentive to expand unchecked. The USA was initially envisioned as a minimal state, allowing for the flourishing of entrepreneurship, individual liberties, and economic and philosophical growth. However, those in power often succumb to the temptation of increasing government size and intervention, dipping into citizens’ wallets under the guise of promoting the general welfare. Unfortunately, a minimal state tends to grow over time, as has occurred not only in the US but also across the Western world.

An informed citizenry, aware that taxes, regardless of their magnitude, equate to forceful confiscation, can exert pressure to minimize state intervention and taxation. The state should not usurp functions that private entities, churches, and local communities handle better. This awareness empowers individuals to advocate for limited government involvement and taxation, promoting freedom and self-reliance while ensuring that the most appropriate entities efficiently and effectively deliver essential services.

TP: Any last words?

JB: Capitalism and morality share a profound relationship, yet the latter often receives insufficient attention in our increasingly mechanistic worldview, which has also corrupted science and reason into scientism. This issue is exacerbated among socialists and Marxists, who believe they can engineer society and human nature—an extreme form of naivety. The emerging woke culture, lacking even the slight objectivity of Marxism, is proving to be even more extreme, placing undue emphasis on hopes, positive thinking, and hedonism as the sole constituents of life.

In closing, let’s address a few issues often wrongly attributed to capitalism: outcomes of wealth, comfort, societal complexity, division of labor, and the subsequent erosion of our moral compass. Adam Smith aptly noted the adverse effects of commerce on human courage and martial spirit, especially under the division of labor, leading to moral deformity and vulnerability to demagoguery. Marx termed this “alienation.” Even the higher classes can focus excessively on their limited work area, forgetting whether they generate social value.

In a similar vein, Hannah Arendt uses the phrase “the banality of evil” to describe Eichmann’s behavior at the trial, which included showing no guilt or hatred for those trying him and claiming he was “doing his job.” Arendt warns of the dangers of technocracy, pointing to the blunted moral conscience of Eichmann, a Technocrat, who reasoned that he was only putting people on trains and did not have the intellectual curiosity to consider their destination and the likely outcome or was casually indifferent.

As we become wealthy, we risk becoming too comfortable, which dulls our moral spirit and sense of honor. We become too tolerant for selfish reasons. Why fight when it does not directly affect us? We learn to compromise when financial costs look higher than the benefits. Constant compromises drain the warrior spirit. I can understand why asceticism is so highly valued in most religions.

Unless we understand our place in the larger ecosystem and how our actions within our limited area of work affect society, we are likely to rationalize or remain unaware of the burdens we may be imposing on society while making money personally. This situation is exacerbated among socialists; at least in the capitalist system, competition and feedback mechanisms exist, which unaccountable bureaucrats don’t have.

Wealth should have only one purpose: to provide a better platform to improve ourselves spiritually.

TP: Thank you so very much for sharing your views with us.

JB: Thank you.