The decomposition of patterns dating back to the Cold War and their ongoing recomposition according to new, but still uncertain parameters, is particularly evident in Africa, where ancient presences are progressively attenuating their influence and new ones are pushing to assert themselves on the continent, despite their own internal problems, while others try return there. An example of it is the fogging of France, the penetration of Turkey, the return of Moscow and the not so clear stance of China.

The reality, however, is more articulated and complex and alliances and hostilities are intertwined in the constant diplomatic game of influences, to which are added imperial and/or neo-imperial dreams, economic interests, internal political needs.

Turkey’s efforts to expand its influence in Africa often align with those of Russia, with both Ankara and Moscow holding back from condemning recent military coups in Sahel and seeking to capitalize on post-colonial resentments growing in the region, especially against France, but widely hostile to the Western economic and political states and architectures (e. g. G7, NATO and EU).

While the analysts look on the Turkish ambitions only towards the Turanic area (Caucasus and former USSR Central Asian republic) and Middle East, Africa is also an important element of the Ankara welt politik and the highly mediatized presence and influence of Turkey in Libya is a mere, even important, part of a broader strategy of influence and penetration in the continent.

A series of military takeovers in West Africa, the latest occurring in Gabon at the end of August, may reveal the extent to which Turkish and Russian efforts converge in trying to leverage political shifts to the detriment of former colonial powers, chiefly among them France, and expand their own influence in the region.

Keen to seize opportunities under the new African governments, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the Russian head of state Vladimir Putin, have refrained from condemning the putschists riding the wave of popular resentment toward the ongoing influence of former colonial powers, their endless exploitation of local natural resources and the failure of Western-led anti-terror operations in the region.

Speaking at a Russia-Africa summit in St. Petersburg shortly after the July coup in Niger, Putin remarked that some manifestations of colonialism remain in Africa and underlie the instability in many regions on the continent.

Erdogan has employed similar rhetoric for years, in particular targeting France, expanding the rift that opposed the two countries in the demarcation of hydrocarbon fields in Eastern Mediterranean waters and the consequent rapprochement of Paris with Greece and Cyprus, and leading to a dangerous confrontation in June 2020 when, when a French frigate under NATO command tried to inspect a Tanzanian-flagged cargo ship suspected of smuggling arms to Libya in violation of the UN embargo, was harassed by three Turkish navy vessels escorting this one. A Turkish ship flashed its radar lights and its crew put on bulletproof vests and stood behind their light weapons.

However, as many other aspects of the Russian-Turkish relationship, also there is a strong background of ambiguity, giving the divergent strategic and long-term objectives. But this ambiguity is present as well with the relationship with NATO, of which Ankara is full member, and EU, and these ambiguities reflect, paradoxically, the firmness of Turkey in finding her own way, space and ambitions, regardless the expectations of partners/competitors, but the dreams of Ankara’s leadership could be undermined by intrinsic fragilities, weakness and fracture affecting the country.

In August 2020, just after the coup, the (then) FM Mevlut Cavusoglu visited Mali, putting his opportunism on striking display and openly irritating (further) France and US. However, after the coup in Niger (July 2023), Ankara has been more prudent expressing concern for the toppled President Bazoum and the suspension of democratic framework (the prudence of statement in Niger could be read as concern also for the presence of a quite large group of Turkish aid workers there). Ankara had issued an almost identical statements after the other recent coups, in Burkina Faso in September 2022 and in Gabon in August 2023.

Hyping the attention received from Russia and Turkey is politically advantageous for the juntas, as it allows them to claim that they are not without alternatives while breaking with France. French President Emmanuel Macron openly pointed out Moscow and Ankara of seeking to exciting and exploiting the anti-French sentiment in Africa. “There is a strategy at work, sometimes led by African leaders, but especially by foreign powers such as Russia or Turkey who play on post-colonial resentment,” he already said in a 2020 interview to the Paris-based weekly ‘Jeune Afrique’. “We must not be naive on this subject: many of those who speak, who make videos, who are present in the French-speaking media are funded by Russia or Turkey.”

With the military governments in Mali and Burkina Faso, Russia got the opportunity to expand the presence of the Wagner Group, the Moscow-funded private military company, (even now the fate of these contractors appears uncertain in the whole contingent, giving that for example, all of them were withdrew from Libya). For Turkey, the primary objective is to strengthen military ties through training programs and arms sales, including the named and very coveted combat drones. Turkish military sales to Africa rose to $288 million in 2021 from $83 million the previous year. Turkey now lists 14 clients on the continent: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Chad, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Somalia and Uganda.

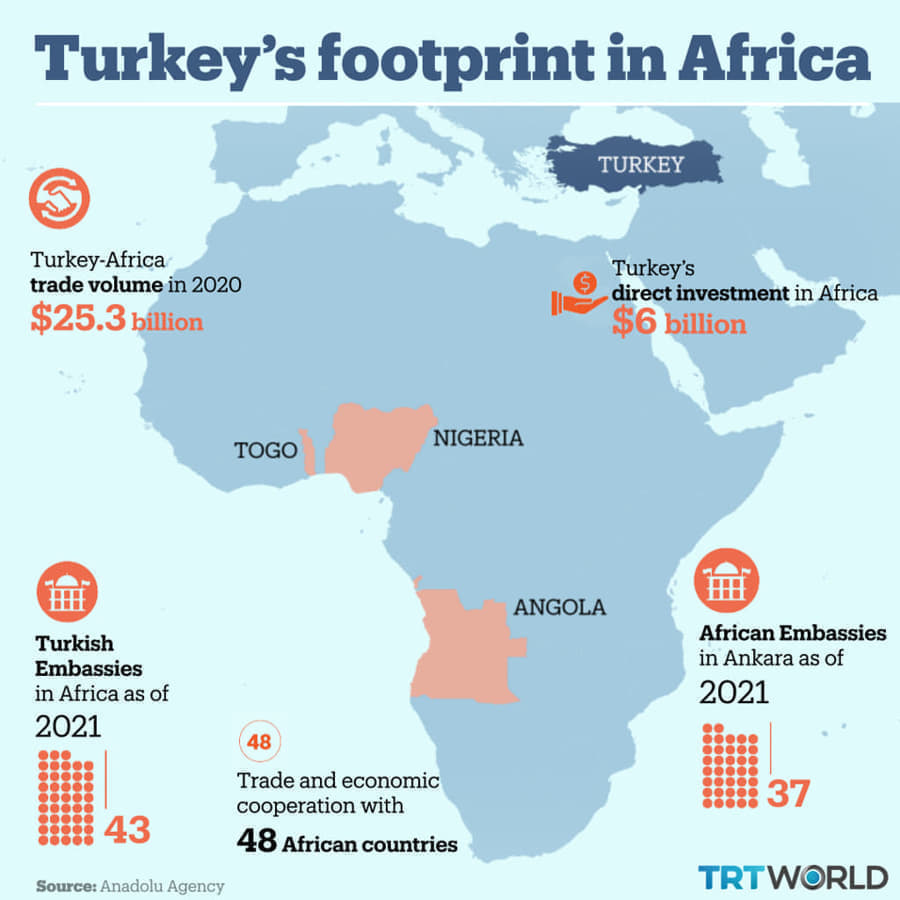

Erdogan expressed his readiness to boost military cooperation with Mali in September 2021 during a phone call with Assimi Goita, head of the junta government (since then, Mali has received several Bayraktar TB2 drones). But Turkey expanded dramatically the diplomatic fingerprint in the continent, opening embassies (today are 43, and there are plans to open new diplomatic facility in Bissau, while the member states of the African Union are 54 and Turkey is the fourth most represented country in the continent after the US, China and France), consulates, development aid offices (22) and expanding trade (more than 100 US$ Billions last year). Turkey had opened its embassy in Bamako in 2010, with Erdogan making his first presidential visit in 2018. There are of course up and downs; while in Mali, the Turkish presence is only in sending drones, in Somalia, where Ankara has a military base in Mogadishu, Turksom, where since autumn 2017 Turkish 300 CO and NCOs, train Somali soldiers (till now 10.000 completed their training programme).

Modern Turkey’s current engagement with Africa officially started in 2005 after Turkey declared 2005 “the year of Africa” and adopted a new policy of “opening up to Africa.” Since then, it was seeing Turkey’s diplomatic venture in the continent because, according to the Turkish foreign ministry, relations with Africa constitute one of the key foreign policy objectives and opening new diplomatic missions enhances Turkey’s relations with the continent.

Also, Turkey was granted observer status by the AU in 2005 and later became a strategic partner in 2008 with its first Turkey-Africa summit in Istanbul in the same year. Focal points in the Istanbul summit were a “common future,” “cooperation” and “solidarity” between the participating parties. Moreover, both Turkey and African partners have agreed to implement a concrete programme of action based on equality, mutual respect and reciprocal benefits. The second summit between Turkey and African states was held in Equatorial Guinea’s capital, Malabo, in 2014 in accordance with the Istanbul Declaration’s follow-up mechanism, which demarcated that summits are to be held every three years and ministerial review conferences every three years. In Malabo, the Joint Implementation Plan for the period of 2015-2019 was accepted by the participants.

Nevertheless, Turkey’s Africa policy is not limited to periodical summits. Official visits to African countries play an important role in developing Turkey’s cooperation with Africa too. In this regard, Turkish President Erdoğan has visited 30 different African countries, including war-torn Somalia, a couple of times in the last 15 years. This is usually considered a record for a non-African leader. After a two-year interruption due to the coronavirus pandemic, he started his Africa tour once again from Angola, Togo and Nigeria in October 2021 and make another tour in 2022, visiting DRC (where it was signed a pact of military cooperation and assistance) and Senegal.

Turkey’s history in the continent goes back to the 16th Century when the Ottomans first arrived in North Africa. Later, Ottoman territory expanded across the shores of the Red and Mediterranean seas and towards the Sahel region. The Ottomans remained a ruling power in Africa for four centuries and established five separate administrations in Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt and Eritrea. However, in 1912, Ottoman forces retreated from Libya, the last stronghold in the continent, expelled by the Italian colonialist push. Although it is quite rich, the Ottomans’ historical legacy in the continent still remains unexplored by academics. In addition, during the Republican era, Turkey focus shifted to the West.

While Turkey carries some Ottoman baggage in North and East Africa, Russia has no colonial past in the region, which gives it an edge in terms of perception and now Putin emphasize it as tool for his assault to global power. In addition, bilateral ties fostered during the Cold War make things easier for Moscow than Turkey, which remain a member of NATO and could awake some suspicions. Whereas Turkey (along with Russia) was seen as a rival of France in Mali, the main rivalry in both Burkina Faso and Niger appears to pit France against Russia.

Niger, giving her geographical position as hub linking western and eastern Africa, carries more importance for Turkey’s opening to Africa than Mali. Turkey has signed 29 agreements with Niger since opening an embassy in Niamey in 2012. Erdogan paid a visit in 2013, and the following year, President Mahamadou Issoufou traveled to Ankara. In 2021, Turkish Vice President Fuat Oktay attended the inauguration ceremony of Bazoum, who then traveled to Turkey for a diplomatic forum in 2022, where he met with Erdogan. Many other Nigerien senior officials and ministers have visited Turkey as well since 2021. Bilateral trade stood at $134 million last year, up from $46 million in 2012, and an agreement on military training cooperation was among the deals that (the then) FM Cavusoglu signed when he visited Niger in July 2020. After a phone call with Bazoum in November 2021, Erdogan said that Turkey would help boost Niger’s defense capabilities by supplying it with TB2 drones, armored vehicles and Hurkus light trainer and combat aircraft, in the frame of rearmament policy inaugurated by that country to face the Islamist terrorist pressure. At least six TB2s have been delivered to Niger since then, but claims of plans for a Turkish military base in Niger have not been confirmed.

The junta in Niger withdrew the country’s ambassadors from France, Nigeria, Togo and the United States, but revoked military deals with only France. It is unlikely to halt defense cooperation with Turkey. Reluctant to explicitly condemn the coup and be hostile against an intervention by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Ankara look to protect her interests and enlarging it furtherly in the sub region of Sahel, expel France and limit the influences of US, Russia and China.

As above said, Niger is in a critical geographical point and in a peculiar momentum and the persistent instability of Nyamey, despite the ongoing normalization with US (which recently de facto accepted the quasi legitimacy of the military junta) may represent a risk for the subregional and continental ambitions and plans of Ankara.

The low intensity conflict in Niger (as well for Chad) could be sealed with the one which affect the instability of South-West Libya and Western Fezzan. After years of heavy, but ineffectual, civil war, the country is still split in two (officially, while in reality there are at least 5 entities/areas under different power and/or influence). Ankara want to defend the position acquired with the Tripoli-based institutions (also based on the fact that Turkish military appeared to be the key element of the struggle against of the general Afthar-led forces offensive, which, by the way, were supported by hundreds of Russian military contractors and thousands of mercenaries from Niger, Chad, Sudan). Turkey might be in tactical convergence with Russia, but she damaged by the Russian factor elsewhere in Africa as it is in Libya. Turkey wants to keep the agreements on defense, maritime delineation and energy exploration with the Tripoli-based government, with the political aim to marginalize Italy and (again) France from Libya.

The changing political landscape in Africa may offer Turkey opportunities to expand its areas of influence, but any prospect of gaining new footholds on the continent, such as its permanent base in Somalia or its de facto base in Libya, appears unlikely at present.

But as mentioned above, under a general view, Erdogan in its look to dismantle the legacy of Ataturk, may be in unconsciously, he walks in the path of political doctrine of the last period of Ottoman Empire.

With the decline of the Ottoman Empire, playing on the contradictions of powers to protect its interests, it was the central doctrine of the international policy of the Sublime Porte and particularly of Sultan Abdulhamid II.

The bet quickly became untenable and led the Empire to numerous setbacks. The construction of the Republic in 1923 must initially be understood as an attempt to break with this strategic framework.

Turkey of Erdogan has been able to reconnect with a certain influence and advance its pawns, it is, systematically, by benefiting from the contradictions of world powers, seeking first to exploit all the interstices from which it could benefit.

The opening of two military bases abroad, one in Doha (formally opened in 2015, even training programme existed since 2022), the other in Somalia, was firstly the result of local conflicts and the disengagement of Western states having a preponderance history in these regions. The dynamism of its defense industry, materialized by the production of drones or the delivery of a drone carrier for the national navy, directly contributes to Turkey’s interventionism in numerous conflicts.

But here again, it benefits from international contradictions and confrontations, like the support of Azerbaijan, against Armenia, getting advantage of Russia’s strategic refocusing in Ukraine (and consequent quagmire).

Likewise, recent years have seen Turkish companies enter new markets. Still using the African parameters, in 2022 there were 225 of them operating on the African continent, particularly in the construction, textile and infrastructure sectors, compared to only three in 2005. Turkey has notably benefited from the challenge to the monopoly of the former colonial powers initiated by other actors and in particular China.

Above all, in the last period, diplomatic balancing has become a trademark and a means of affirmation for the Turkish president, oscillating between Moscow and Washington, asserting his place in NATO, slowing the adhesion of Sweden (blackmailing Washington in order to get spare parts for the F-16’s fleet, practically grounded) the Atlantic Alliance, and applying for membership within the Bejing tool of SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organization), or playing a pivotal role between Russia and Ukraine.

Ankara’s diplomacy aims to obtain, piecemeal, as many concessions as possible from appropriate allies. It thus allows Russia to circumvent international sanctions, to benefit from massive imports of energy products.

However, Turkey’s current policy thus risks transforming strategic opportunism into critical vulnerability, but there are, as above mentioned, elements of fragility. Turkish foreign trade is already experiencing a record deficit due to the exponential growth of Russian hydrocarbon imports. The country has lost its food sovereignty, and entire sections of its economy are directly backed by foreign financing, particularly from the Gulf states. The development of its defense industrial base, despite some important achievements, like an indisputable experience on the drone sectors, still suffers from critical dependencies for fundamental parts, such as engine construction, which obstructs the path to real strategic autonomy.

To encourage foreign investment and strategic rapprochements, a large part of the country’s state property productive assets has been privatized and dependence on food and energy imports fuels inflationary loops (and the new finance minister signalled to further privatize important sectors, but his problem is to privilege domestic buyers and avoid foreign influences and the potential domestic buyers have limited finances).

Finally, building the country’s power to mirror the game of the great international powers weighs heavily on Turkish society. Faced with the loss of sovereignty, this strategy fuels a nationalism encouraged by political power. To reassure partners about the reliability and stability of the country, this path encourages a tenuous, and often brutal, supervision of the population which participates, moreover, in the growing questioning of secularism.

The imposition of religion in the political field and in all dimensions of society cannot mask the growing secularization of the Turkish population, and particularly its youth. The need for the AKP to increasingly resort to religious themes in its mode of governance constitutes, ultimately, both an admission of weakness and a signal sent to the outside world. It helps to channel its youth and impose its political agenda, but at the same time reinforce the secularism in social and geographical areas. It also supports Turkey’s strategic realignment, both economic and diplomatic, giving guarantees to the States of the Gulf, North Africa, Central Asia and the Balkans which now constitute strategic partners that Recep Tayyip Erdogan intends to use as support (especially the ones, like in the Gulf, which have a financial leverage) to help the recovery of the national economy and lower the prices (it should be recalled that the ‘Erdoganomic’, or lower prices, was a key element of the electoral successes of AKP).

How much longer will this strategic opportunism allow Recep Tayyip Erdogan to remain in power in the face of a shrinking social base? This is an essential question for the Republic of Turkey, on his centenary.

Enrico Magnani, PhD, is a retired UN official and expert in military history and international politico-military affairs.