1 – During his recent speeches in Marseilles (September 2023), Pope Francis reminded us of the “right of migrants to remain in their homes and lead a dignified life.”

A “right” implies a relationship of exigibility, between the holder of that right and any person, physical or moral, obliged to recognize and respect it. In this context, the holder of the right is the migrant; the person obliged to guarantee it is primarily the state.

The Pope thus understands that the right to remain in one’s home is primary, antecedent to the right to leave one’s homeland. Migration from one country to another must be a free choice, rather than a constraint for many, provoked by violence of all kinds: hunger and thirst, war, misery, persecution, ideological madness. This notion deserves a closer look.

2 – In the expression “chez soi” (“in your own home”), the word “chez” comes from the Latin “casa” (“house”), which gave rise to “case” in French. It designates the fundamental dwelling, the “thatched farmhouse” of the song, which remains at the bottom of one’s heart wherever one goes, and whose intimacy and personal character is emphasized by the pronoun “soi” (“your own”).

The “chez-soi” is thus not just a legal domicile, nor a more or less ephemeral residence. It is the human, protective place, inscribed in a physical and spiritual space, where warm, living roots have taken root. The place of initial “little things” where, as in César Isella’s poem, everyone always returns, in one way or another, because it is the place “where they loved life.”

The “right to stay at your own home” is therefore the right to keep these roots, and to continue to live from them, where they were born. A rootedness that cannot, however, retain this vital virtue unless it is itself continually nourished and invigorated. No one settles near a dried-up tree or a dried-up spring without being forced, sooner or later, to migrate.

For a “home” to remain such, its roots must be nourished by a tradition, both cultural and religious, that is preserved and enriched, a tradition that is nothing other than the permanence of the identity of a “home” renewed over time.

3 – The purpose of the “right to remain in one’s own home” is therefore not limited to the physical maintenance of a place. The purpose assigned to it confirms this. The right to remain in one’s own home is “to lead a life of dignity.” The right to remain in one’s own home thus implies the right to a dignified life.

Dignified life” does not simply mean “feeding, growing and dying by oneself” (Aristotle, Treatise on the Soul, II 1, 412-414) in a chosen place, after having enjoyed it in a variety of ways. Nor does it simply mean living in conditions of material or economic sufficiency, as expressions such as “dignified housing” or “dignified working conditions” might suggest.

Dignity, in fact, is an essential and inalienable property of the person, insofar as he or she is rational and free. It is the radiance of “that which is most perfect in all nature; namely, that which subsists in a reasonable nature” (Thomas Aquinus, Summa theologica, Ia, q. 29, a. 3.). It follows that “dignified life” is that which enables everyone, according to their natural vocation, to live and grow to the height of humanity, the material conditions mentioned above being ordered to this vocation. Respect for natural law, which reflects divine wisdom, the promotion of the family as the original “home,” education in truth, love and transcendence, and the cultivation and practice of justice are the primary conditions for a dignified life.

4 – Thus founded on the principle of human dignity, which French law recognizes must be protected against any infringement (art. 16 of the French Civil Code), the “right to remain in one’s own home and lead a dignified life” reveals its true dimension: it is a fundamental right with, as such, universal value.

In this respect, it is not the privilege of the migrant. Its purpose is not simply to measure the freedom to come and go, to stay at home or go into exile. This right is the ultimate expression of every human being’s natural inclination to live in society, not only to find security there, but also—and above all—to find and keep that deep-rooted “home” that is destined to be the nurturing place, familial and social, for his or her total human, material and spiritual fulfillment.

The “right to stay at home and lead a dignified life” also belongs to citizens of host countries. Being universal, it is fundamentally equal for those who welcome migrants into their homes and for those who, having seen this right violated, are forced into exile.

Two conclusions, at least, can be drawn from this, which are rarely present in discourses on migration.

5 – The first is that the fundamental nature of the right being invoked conditions not only the political freedoms of those who hold it. It also sheds light on the state of health of societies that are, or are not, in a position to guarantee and promote it.

Societies that not only exhaust the economic capacities of their members, but also feed systemic lies and manipulation, moral and mental degradation, educational ruin, sanitized homicide or other forms of violence—physical, legal or ideological—contrary to the dignity of the human person, are certainly not the right setting for the creation or permanence of a “home” enabling its members to grow humanely.

So it is, of course, with the societies that migrants are forced to flee, precisely because of this. But the same is true of the societies they join, when these societies offer them nothing but their materialism, their self-hatred, their break with natural law and the degradation of their culture and mores. So, it is hardly surprising that these migrants cannot find a national “home” in which to integrate. Failing that, they prefer to try and rebuild the community they were forced to leave.

Nor are migrants the only victims of this decivilization. The first are the citizens of these societies, where the common good, in particular, is no longer the raison d’être of the law. Many of them are struggling against their own uprooting and that of their children. As a result, they are at risk of becoming exiles from within, forced to nurture a “home” against the grain, from family to workplace to school, that preserves their Christian identity, historical tradition, language and culture.

6 – The second conclusion is that if this “right to remain in one’s own home and lead a dignified life” is fundamental and universal, and thus equal for all, then it is particularly binding on the migrant himself. They are obliged to respect it in those who welcome them—or are unable to welcome them. For them, too, the right to “stay at home and live with dignity” and in peace is prior to the right to migrate. It is therefore prior to the rights of those who intend to migrate home. Indeed, it is even among those who do not migrate, by hypothesis, that the exercise of the right to remain at home to live with dignity and in peace is perfect.

It is therefore not without subversion of the natural order that we try, under the guise of charity, to make the citizens of host countries believe that their right to stay at home should take a back seat to the right to migrate of those who cross their borders. In the dialectic imposed by Pope Francis between the “culture of humanity and fraternity,” supposedly virtuous, and the “culture of indifference,” supposedly criminal (Pope Francis, Address, Palais du Pharo, Marseille, September 23, 2023), there is a legal and human space which is that of respect for the fundamental rights of all.

When the phenomenon of migration undermines or threatens the security, habitat, culture, way of life or religion of a host country, to the point where its citizens no longer feel at home and can no longer live there with dignity and security, and are sometimes forced to flee, it necessarily undermines what is, for them, a fundamental right. To this extent, the phenomenon is a grave social injustice, commensurate with the rights it violates, which cannot be ignored.

7 – That is why, between the right of some to migrate and the right of others to “stay at home” to live in peace and dignity, a measure is needed to determine the balance between them. This measure is that of the common good—or, if you like, the general interest. Each State, which is its natural guardian, just as it is the guardian of the fundamental rights of its citizens, has the right, and even the duty, to establish this measure, so that the rights of the former do not prevail over the rights of the latter.

This is the condition and limit of any migration policy. It requires the government to determine when it can welcome immigrants, and under what economic and social conditions, and when it cannot. It requires the government to know how to refuse immigration when it appears that it can no longer be integrated and infringes on citizens’ fundamental rights.

To see this as a “criminal indifference” contrary to charity is to be fooled by political fideism, whereas the demands of charity never erase those of nature. Yet for a long time now, we have been hearing the much-needed lesson of Saint Thomas, which no longer seems to be understood, but which must be repeated over and over again: “Divine right, which proceeds from grace, does not take away human right, which proceeds from natural reason” (Thomas Aquinus, Summa theologica, IIa IIae, q. 10 a. 10).

Patrick de Pontonx is a lawyer based in Paris, France.

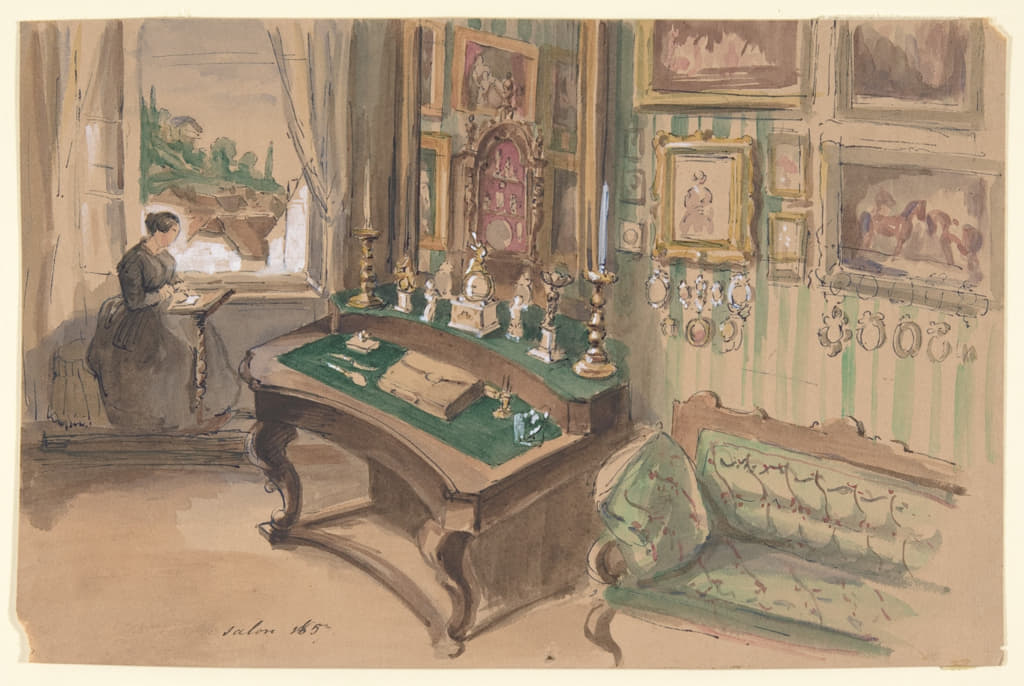

Featured: Salon, anonymous, 1857.