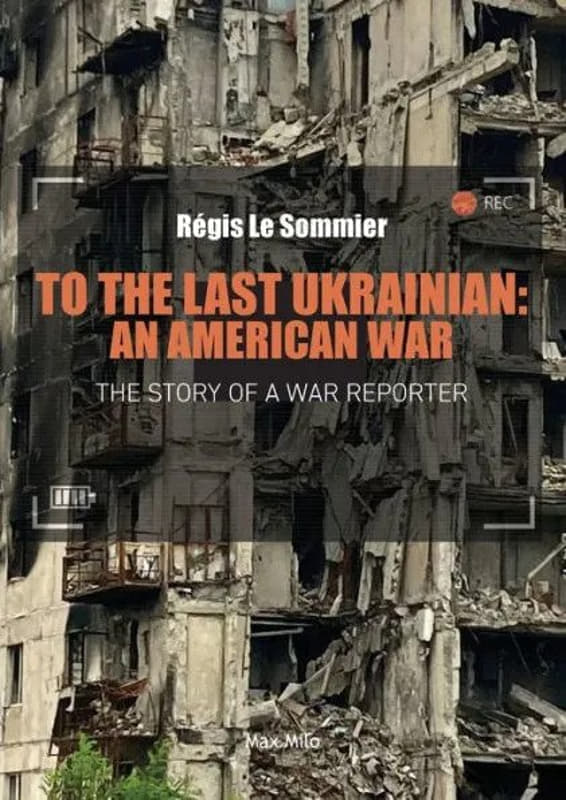

This excerpt is from a very important book on the conflict in Ukraine: To the Last Ukrainian: An American War. It is written by Régis Le Sommier, who was embedded in both the Ukrainian and Russian armies. The account that he gives in this riveting chronicle tells of the perfidy of politicians and the tragedy of ordinary soldiers caught up as pawns in the machinations of geopolitics.

Régis Le Sommier is one of France’s great journalists whose work, spanning thirty years, has received several awards. He is the only war reporter who went to both sides of the front line with the Ukrainian and Russian armies for a year. This is his story.

You may purchase a copy of To the Last Ukrainian: An American War either from Amazon, or from Barnes and Noble.

The Strange Carl Larson

The bus stopped in the center of a village.

“This is the place,” Max announced.

We, the Frenchmen, picked up our luggage and walked about two kilometers to a place designated by the GPS on Max’s smartphone. At a bend in the road, Ukrainian soldiers came to meet us.

“We are French. We’ve come for the Ukrainian legion.”

One of the soldiers made a phone call. A few minutes later, a man of athletic build, dressed in grey and wearing a commando cap on his head, got out of a vehicle.

“You have a military training?” He asked after shaking hands.

Max and Sabri nodded in response. This soldier was American.

“They call me the Grinch,” he said to the Frenchmen who had no idea what this nickname was supposed to mean. Neither did the Ukrainian soldiers around them.

The Grinch is the American bogeyman, a grumpy, greenish character from a Theodor Seuss Geisel cartoon, whose goal is to ruin Christmas. This cultural reference reflected the mindset of this American who naturally believed that the whole world knew about the Grinch. He announced that he was part of a team of American instructors who had come to train foreign volunteers.

“I’m here to put the internationals in order,” he told the Frenchmen. “I am in charge here. Too many people showed up at the center and they had no business being there.”

The French volunteers listened to him without saying a word. Then he moved on to instructions and declared:

“If you have international phones, you’ll have to cut them off or get local SIM cards.”

It was at this point that I told him that Noël, my sidekick, and I were journalists. Until then, he naturally thought we were volunteers. His face tightened immediately. What? Journalists who’ve dared to come out here?

The American was upset, or perhaps he realized that he had said too much? He chose to deal with the problem in a radical way:

“You don’t belong here,” he told me in an icy tone.

I protested by invoking the right to information:

“The French public has the right to know what is happening to their fellow-

citizens who’ve come to fight alongside the Ukrainians.”

The man was embarrassed. As a good American, and even though his presence here fell in the realm of clandestine operations, he believed that the right to information was sacred, that it was a virtue of his country.

Technically, he had no right to ask us to leave. So, he called his Ukrainian counterparts on the phone and, as if to pass the buck, asked them:

“You don’t want reporters, do you?”

Then he turned to me and with his white teeth gleaming announced:

“They don’t want reporters.”

He then explained his approach in a more conciliatory tone. He had come to help the Ukrainians. He was fighting for the freedom of the people, the great American classic line which I’ve hear since Iraq. However, from the way he spoke to us earlier, this individual clearly had far greater responsibilities. I’ve been around the US military in Iraq so much that I know by instinct who’s in charge, regardless of what they’re wearing.

Judging from the docile behavior of the Ukrainians around him, this man was no simple volunteer filled with good will. He could have just said that he was an instructor, that he was in charge of training, and that he was from the United States, and that would have been enough. But his commanding tone, that “I’m in charge here,” left no doubt.

I did some research on him. I found an interview he gave to the Seattle Times. His name is Carl Larson and he admits to being one of the American instructors who came to help the Ukrainian army against Russia.

But when we were listening to him with the volunteers, everyone was thinking the same thing. The scene was worthy of being in the Hall of Legends. There were also curious elements in his background. He was an Iraq War veteran. He was part of a military contingent that participated in the initial phase of the invasion. Then, he was no longer in the news. And today, was he still in the military? Was he on a mission for the Pentagon? I can’t say for sure. I tried to verify this through contacts in the American

army and in French intelligence, but I did not get any answers. Cover-up is big part of the war in Ukraine.

What I can confirm is that in the recruitment of foreign volunteers to fight in Ukraine, an American veteran was in charge. Another Seattle Times article appeared about him on October 25. It said that after his assignment to select international recruits, Carl Larson trained a unit deployed to the Kharkiv front. Then he returned home. On his role in the selection of volunteers for the Ukrainian Legion, it is written that he was reluctant at

the beginning, partly because of the recruits who were “unstable or without military experience.” The article went on to say that he himself was reluctant to join the Legion for fear of not being properly utilized.

“Finally, after discussions with Ukrainian officials, he agreed to select and train a unit before it went to the front.”

We had to leave quickly after we revealed ourselves to the American. We were not allowed to wish our friends well. Just a look, a little wave before they boarded an Opel Corsa, to my great surprise, registered in Essonne and driven by the American. The day after this hasty departure, Sabri explained to me in a text message that they had left by bus for a front line where they had to relieve a unit. They signed a commitment to stay until the end of the war.