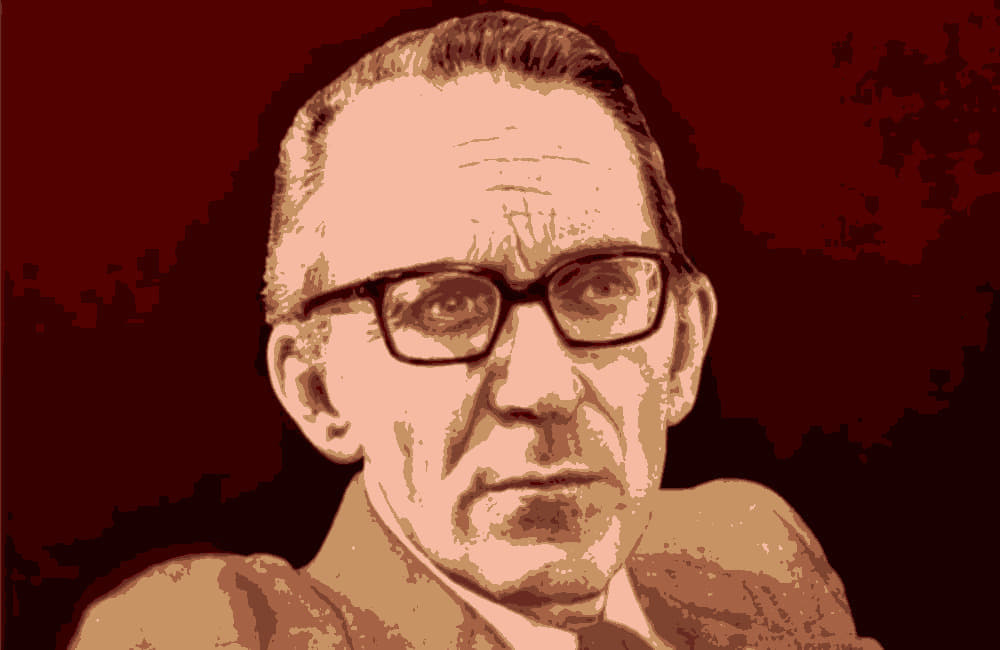

Philosopher, journalist and essayist, Giorgio Locchi (1923-1992) was one of the tutelary figures of non-conformist thought, which deeply influenced two streams: the New Right and Neo-paganism (with the myth of the Suprahuman). In this interview, his son Pierluigi Locchi explores the essential ideas of his father. The interview, conducted by Eyquem Pons, appears through the kind courtesy of Revue Éléments.

Eyquem Pons (EP): Many readers are unaware of the very existence of Giorgio Locchi. Can you resituate who he was? His life, his struggles, his passions?

Pierluigi Locchi (PL): I will answer your question by mentioning some key stages in his life.

Born in Rome on April 15, 1923, my father entered the Nazareno College by competitive examination at the age of ten. Four years later, his Italian and Latin teacher, Padre Vannucci, gave him a book on his fourteenth birthday with these words: “This book is on the Index, but as you will get there one day anyway, I want to be the one who gave it to you. This book was The Birth of Tragedy Out of the Spirit of Music by Friedrich Nietzsche. My father remembered it all his life: “Thanks to him,” he confided to me one day, “I discovered that others felt the same things as me!”

At the end of the war, just 22 years old, my father had to give up higher studies in philosophy that he would have liked to pursue, since he had to provide for his parents quickly. Having opted for a doctorate with a faster course, in philosophy of law, he had nevertheless been chosen by his professor to succeed him in the chair of philosophy of law at La Sapienza University in Rome. Unfortunately, for financial reasons, he could not afford to wait the necessary number of years and took up a career as a journalist. This took him to Paris in 1957, as a correspondent for the Roman daily Il Tempo, where he remained until the end of his life.

The 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s saw Girogio Locchi holed up in his office, but he did end up finding the audience that the University of Rome had not been able to give him, initially in the circle of young French intellectuals frequenting the Librairie de l’Amitié and gathered around the magazine Europe-Action by Dominique Venner and Jean Mabire, among whom a certain Alain de Benoist already stood out, and then especially in the community gathered around GRECE ( Research and Study Group for European Civilization) of which he was one of the co-founding members. Though my father was also a member of the editorial board of the magazine Nouvelle École, to which he contributed very regularly until 1979, his role was rather different. Being the thinking head of this new movement, Locchi was more than a philosopher, journalist, essayist and thinker; he was, as Guillaume Faye rightly wrote, “an awakener and a dynamiter,” exactly in the spirit of Friedrich Nietzsche.

And a whole generation of intellectuals has drunk from the spring of this master, who, after having evolved within or around GRECE and then branched off, still constitutes today the spearhead of non-conforming thought, starting with Alain de Benoist, today the undisputed leader of the New Right. And “old-fashioned” master, my father transmitted a lot orally. I remember in particular the two years when he received on Tuesday evenings in our house in Saint-Cloud, near Paris, a whole assembly of students and young workers, eager for knowledge, gathered in particular for two training periods, one dedicated to Richard Wagner and the other to Friedrich Nietzsche. Who would have believed that? On this double filiation rests a good part of the intellectual formation of those who played and still partly play a preponderant role in European nonconforming culture.

Another great passion of my father was music, and perhaps above all the work of Richard Wagner. I will be eternally grateful to him for letting me discover Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg at Bayreuth at the age of eleven! Among his other areas of interest, some, such as history, linguistics, our Indo-European past, are well-known. Others, such as quantum physics or logic, are less so. All his knowledge, all his passions, however, were always put by him at the service of a work of unveiling, with Giorgio Locchi holding particularly to his role as historian.

If the history of which he speaks to us is clearly part of a suprahumanist perspective, which I will have the opportunity to speak about, he has always insisted on the role which must be that of any historian, which is to carry out an analysis, sine ira et studio, without hatred or passion, as Spinoza said, that is to say without letting his own necessarily partisan positions influence the way in which this analysis is presented; therefore without taking sides in the exposition of the facts, or more exactly, specifying each time in what perspective, from what point of view the facts are presented. From there, the fight of his whole life became one of working for the understanding of what the suprahumanist myth is, what are the different forms in which it has successively manifested itself for more than a century and a half, and in what it carries within it, which is the renewal of our civilizational heritage. It is a work of both historian and philosopher, the same myth taking each time, from Wagner to Nietzsche, from Heidegger to Locchi, to name but a few, a new form in whoever carries it within him, by the laws of becoming.

EP: What does it bring to this family of thought?

PL: I am always wary of exaggerated enthusiasm and grandiloquent assertions, but I have to repeat the terms used by Guillaume Faye in his “Archaeofuturist reflections inspired by the thought of Giorgio Locchi”: “I weigh my words carefully—without Giorgio Locchi and his work, which is measured by its intensity and not by its quantity, and which also rested on a patient work of oral formation, the real chain of defense of European identity would probably be broken.”

It is therefore a major contribution in two ways, and major for looking to the past, for considering our present, or for projecting ourselves into the future. Major, first, for looking to the near past, considering his work of formation of the new generations of the 1970 and 1980s, generations which in France and in Europe carry today the most radical alternative and innovative thought in face of the system in force, a true system “to kill the people,” as Guillaume Faye rightly wrote. Second, major for looking to the distant past, considering the centrality, that he was the first to grant in the post-war period, to the significance of the Indo-European fact. Regarding our present, we owe him the highlighting of the epochal conflict, recently appeared, between the opposite historical tendencies, irreconcilable and irreducible to each other, which are the egalitarian bimillennial tendency and the suprahumanist tendency. This is a particularly valuable key to understanding. Moreover, the suprahumanist perspective allows the definition of what is common to the various sensibilities and organizations that compose it, beyond the visions and the individual or partisan specificities. As for the future, it is by this same suprahumanist perspective that Locchi allows us to think the alternative to the anthropological decline that Europe is experiencing and to aim at a rebirth of Europe that is only conceivable by the regeneration of our history.

EP: What is the importance of the two works, Wagner, Nietzsche et le mythe surhumaniste (Wagner, Nietzsche and the Suprahumanist Myth), and Définitions (Definitions) by Giorgio Locchi?

PL: First of all, a clarification. Only the essays that appeared in Nouvelle École some fifty years ago are being “reissued” in Wagner, Nietzsche et le mythe surhumaniste—and the half-century that has passed is in itself an answer to your question. Wagner, Nietzsche et le mythe surhumaniste remained unpublished until now. Even though it takes up the theme of Nouvelle École, no. 31, this book is entirely reformulated in the perspective of the author’s open theory of history, which constitutes a key to interpretation briefly sketched out in one or two writings published in France in the 1970s, and brought out here for the first time. This is therefore its first presentation to the French public.

Giorgio Locchi’s work is central for those who want to think about the new European renaissance. It even constitutes a true unveiling, Locchi allows us to understand how and why, after having passed through pagan antiquity and the Western Christian cycle, European identity finds itself today, in a world undergoing profound change, in the midst of forgetting itself, for some, and in the midst of rediscovering itself, for others.

Even unfinished, his work represents for me a true cornerstone of our vision of the world, in the same way as the works of Wagner, Nietzsche or Heidegger, which is why I am delighted that the Iliad Institute is committed to publishing in the coming years the complete texts written by the Roman philosopher.

EP: What is the place for suprahumanism today? And what is the difference between anti-egalitarianism and transhumanism?

PL: I will answer in one or two sentences, by affirming first of all that the suprahumanism corresponds to the crossing of a new stage by the European man and the European civilization, and that by this very fact it is situated in a stage of conscience superior to the one of egalitarianism—which cannot be the case of the simple anti-egalitarianism that is satisfied with inverting a scale of values that would not be convenient for it in egalitarianism. I will also add that transhumanism corresponds to the egalitarian way, to face the anthropological mutation that we know today, and a way whose harmful consequences can be fought only by the suprahumanist vision.

EP: Could you elaborate further?

PL: Certainly, I am well aware of the innovative aspect of the “suprahumanist principle,” and it is therefore necessary, here more than ever, to define the terms we use.

Suprahumanism is this new historical tendency whose founding myth appeared almost at the same time in Wagnerian dramas and sacred scenic representations and in the Nietzschean philosophy and poetics. The suprahumanist tendency spread like wildfire throughout Europe, which in the second half of the 19th century was largely ready to welcome it, in all artistic, cultural and political circles. The founding myth that animated this tendency carried with it a new vision of historical time, the one that Heidegger would define as “authentic temporality,” in which man expresses his historicity, his being-for-history, and that my father named the “three-dimensional conception of historical time,” a spherical vision of historical space-time.

This conception was consubstantial with the work of the authors of the German Conservative Revolution, as with that of a Gabriele d’Annunzio and even of a Charles Maurras. I quote Giorgio Locchi:

“The suprahumanist conception of time is no longer linear, but affirms the three-dimensionality of the time of history, time inextricably linked to that one-dimensional space which is the very consciousness of every human person. Every human consciousness is the place of a present; this present is three-dimensional and its three dimensions, all given together as the three dimensions of physical space are given together, are the actual, the become and the to-be.

“This may seem abstruse, but only because we have been used to a different language for two thousand years. Indeed, the discovery of the three-dimensionality of time, once made, turns out to be a kind of Columbus egg. What is indeed human consciousness, as a place of time immediately given to each of us? It is, on the dimension of the personal becoming, memory, that is to say the presence of the past; it is, on the dimension of actuality, the presence of the spirit in action; it is, on the dimension of the future, the presence of the project and of the pursued goal, project and goal which, stored and present to the spirit, determine the action in progress.”

Giorgio Locchi’s first contribution is precisely to highlight this kinship beyond the strong specificities of each one; this common vision of history; this way of feeling man as a historically free being, which constitutes an absolute novelty: “What we have called up to now the past, the historical past, exists in fact only on the condition of being in some way present, and present to consciousness. In itself, as the past, it is insignificant, or more precisely, ambiguous: it can mean opposite things, have opposite values: and it is each of us, starting from our personal ‘present’, who decides what it should mean in relation to the foreseen future.”

Likewise, Locchi notes, suprahumanist authors “always attach the idea of ‘myth’ to that of ‘revolution,’ within the framework of a conception of history in which the linearity of historical becoming is no longer more than an appearance, in which the ‘origin’ returns in each ‘present,’ is born from each ‘present’ and rises from each ‘present’ toward the future in a project.”

Suprahumanism, as defined by my father, is therefore not an expression or a trend among others, but the common matrix of all artistic, literary, cultural, political or metapolitical expressions aiming at the rebirth of our European civilization, whenever the latter is seen as having come to the end of a cycle and condemned to “rebirth or death.” Another definition—in a way, the term “suprahumanism,” was chosen by Locchi in homage to the Zarathustrian myth of Friedrich Nietzsche.

EP: We are indeed moving away from anti-egalitarianism.

PL: If every suprahumanist is, by definition, in the camp opposed to the egalitarian tendency, every anti-egalitarian does not necessarily belong to the suprahumanist camp, since there is also an anti-egalitarianism that claims egalitarian values simply inverted, such as Satanism, for example.

It should be noted here above all that the appearance of the new suprahumanist historical tendency has allowed the two-thousand-year-old egalitarian tendency to become aware of itself and its unity beyond the differences of the religious, philosophical and political currents that compose it. This explains the ever-increasing “unnatural” rapprochements between the Church and communist unions, between financial oligarchies and anarchist or revolutionary “ecologist” movements, and so on.

There remains the question of transhumanism. Independently of the lexical proximity with the term of suprahumanism, which readily creates at times a confusion, what makes the question particularly complex, is that one meets supporters and detractors of transhumanism in the egalitarian camp and in the superhumanist camp, each one going off its own definition, privileging this or that aspect, and ignoring others.

Let’s try to see more clearly.

Here too, the work of Giorgio Locchi is of great help, but I must once again move the cursor and refer first this time to his description of the three great stages passed by man in the course of his history, and which correspond to three types of social organization. There is no question of going into detail here about hominization, the Neolithic revolution and the contemporary technological revolution. I refer, in particular for the first two, to the second part of the study on ” Lévi-Strauss et l’anthropologie structurelle [Lévi-Strauss and structural anthropology],” in particular in Définitions.

However, I point to an essential observation: where man transforms his environment, he transforms himself. The first man created himself by giving himself, through culture, the means to live in spite of his incomplete biological condition—indeed, where the animal is inscribed in the specific environment given to each species, benefiting from a mode of use inscribed in its genetic code, man is born incomplete and defenseless, exposed to the hostility of the world. No fur to protect himself from the cold, no claws to defend himself, etc. In other words, where the animal has received everything by its own inheritance, where it is born finished, man, in addition to his own biological inheritance which leaves him unfinished, needs a period of extra-uterine gestation, then a long period of education, to appropriate the cultural inheritance, starting with language, which will make him become man. If, as an unfinished mammal, man survived, it is because he forged himself, by forging his own culture, that is to say the weapons that allowed him to create his own environment; he adapted to his needs according to the objectives that he set himself. These can obviously differ according to the types of man and the latitudes, but a constant is common to this first hunter-gatherer man—he is himself both subject and object of his own domestication.

EP: Then the Neolithic revolution.

PL: Things changed radically with the Neolithic revolution, when man added a new string to his bow, that of domesticating living nature. Now, domesticating living nature implies sedentarization and specialization, and therefore a radical modification of the social organization. Locchi indicates in several essays, short and concise, of a crystalline clarity, how our Indo-European ancestors faced this revolution, making their own this new type of man, assuming this splitting of the originally unique man in different types of men and solving the problem through the communitarian link and the assumption of a common destiny. They thus projected a pantheon in which the gods, human and too human, embody the ideal of a world where man has become multiple, while reflecting in their functional trilogy—Jupiter, Mars, Quirinus to put it in the manner Roman—the three social functions (priestly, warlike and productive) of Neolithic society, which the Indo-Europeans therefore conceive of as a community of destiny, chosen and even desired, with its uncertainties. The acceptance of this becoming, in which divided man rediscovers his original unity, is what we call the tragic meaning of history. But Locchi also indicates how, for another part of humanity, this revolution was, on the contrary, a curse, a bitterly regretted loss of the original unity of the first man, a metaphysical unity that must be rediscovered. For this part of humanity, history is to suffered; it is the consequence of a transgression, an evil that must be rid of in order to reconnect with unity, to rediscover the uniqueness of the first man. This other humanity therefore ideally sees itself as One—and expresses it in monotheism. We see here how, already, by redrawing the picture of this previous revolution, we are led to speak of the meaning of history, and of opposing visions of history.

Which brings us back to transhumanism, which is perhaps the most striking symbol of the third great stage just taken by man, that of the domestication of matter-energy, and where man is once again transformed into transforming his environment.

We must of course start by agreeing on the term. This can be understood (at least) in two ways. Either we mean by transhumanism all the new techniques of appropriation, including of man himself by man, that the domestication of matter-energy now allows—biotechnologies, genetic manipulations, but also artificial intelligence and techniques of influence, for example—and in this case transhumanism is an objective fact, a concept that can sum up in one word the new human situation; either we see in transhumanism the objectives that some think they can achieve thanks to these new techniques—and in this case transhumanism is defined according to subjective data specific to the one who judges it “immoral,” because of transgressing or even aiming at abolition of “natural” and “eternal laws.” Now, the key to the domestication of matter-energy enables us to understand that we have no choice but to “deal with” its consequences; and the key to the epochal conflict between opposing tendencies enables us to understand that we find ourselves faced with the same alternative as during the Neolithic revolution—accept the transformation of man or reject it out of nostalgia for the previous state. Our Indo-European ancestors took up the challenge and adopted this transformation. This is exactly what the suprahumanists intend to do, faced with the challenge of modernity.

EP: What can a young reader find in Locchi’s demanding texts?

PL: I remember how, on reading these texts, different elements of my vision of the world, of my way of feeling things, of my analysis of past or recent events found an interpretative key that satisfied both my intellect and my heart, and how they have allowed me to structure my thinking and guide my action throughout my life.

I can only wish the young reader to experience the same sense of unveiling that I experienced for myself many years ago. As a young auditor of the Iliade Institute’s training cycle told me, Locchi’s thought is a “radically modern thought, turned towards the future and which intellectually equips anyone who appropriates it, whatever the field in which he will exercise his talents: artistic, literary, cultural, political or metapolitical.”

EP: Giorgio Locchi developed the idea of “interregnum,” a transitional phase in our history. What does that mean?

PL: As mentioned, we are witnessing the emergence of a third man, even more specialized and socially divided, and therefore, from our European point of view, even more under the obligation, on pain of pure and simple disappearance, to find his unity, his fulfillment in a community of destiny based on a new origin, just as there was a new origin for the second man, a new origin expressed with Homer, with Greek tragedy, the Germanic Edda, Indo- European in its various forms.

This new origin naturally claims continuity, the appropriation of our European heritage, but also requires its overcoming. This new origin—and the Locchian teaching takes on its full meaning here—appears in the form of a new myth. And just as the works of Homer, or the Eddas, or the Rig-Veda embody the European worldview of the Second Man, the suprahumanist myth, as represented by Richard Wagner and formulated by Friedrich Nietzsche, embodies the worldview of the European Third Man. This is the subject of the second book published by the Iliad Institute, Wagner, Nietzsche et le mythe surhumaniste (Wagner, Nietzsche and the Suprahumanist Myth).

EP: The Interregnum we are experiencing today corresponds to the period when the two epochal tendencies mentioned above clash without one or the other having really won.

PL: The interregnum will last as long as this conflict between the egalitarian tendency, certainly the majority, but shaken, and the suprahumanist tendency, minority but more determined than ever, is not resolved. We can also say that the interregnum will last as long as the partisans of a European response to the challenges of modernity rise up against the very people who use transhumanist techniques to cause peoples to regress to a stage comparable to that of the animals, enclosing them in an eternal materialistic and hedonistic present which is none other than the end or exit of history. The interregnum will cease only in the event of the total victory of the suprahumanist tendency, or the complete eradication of its representatives.

Contrary to a Dominique Venner who, even if he did not know when it would take place, did not doubt the awakening of Europeans, Giorgio Locchi does not pronounce on a final outcome, and limits himself to indicating that the choice is always possible as long as men will carry within them the suprahumanist myth. In this he is on the same wavelength as Nietzsche, who gave us a first vision of this interregnum by describing man as this bridge stretched between the Beast—the last man—and the Superman, whom he calls for.

EP: Since one of the two books is a collection of definitions, is there a quotation that could summarize or introduce Locchi?

PL: Just one seems difficult to me to find. So, I’m going to skip this.

EP: In spite of a certain mutual affection, Nietzsche nevertheless wrote a pamphlet against Wagner. Isn’t it problematic to present them both as the fathers of suprahumanism?

PL: On the value of these pamphlets (The Case of Wagner, Nietzsche contra Wagner)I refer to the entire chapter Locchi dedicates to the “Nietzsche Case,” which answers your question in a detailed and even “definitive” way, according to Paolo Isotta, an Italian musicologist and author of the afterword entitled, “La Musique, Le Temps, le Mythe” [Music, Time, Myth], where a Stefan George, for example summarizes rather dryly: “Without Wagner, there would be no Birth of Tragedy; without the awakening provoked by Wagner, there would be no Nietzsche…. The Wagner case is in reality the Nietzsche case itself.”

I will limit myself here to quoting two extracts from this chapter:

“Nietzsche drew in philosophical terms the structure of the suprahumanist myth and, by a new language, conferred the first evidence of the implications of this myth. But this myth already existed, because it was represented by and in the Wagnerian drama. Nietzsche did nothing more than give it a ‘name’ and a ‘philosophical’ formulation.”

And further on:

“The fact that Wagner and Nietzsche, one by representation, the other by formulation of an identical myth, create the ‘mythical field’ of suprahumanism and insert it concretely into history, does not mean, moreover, that below the respective representation and formulation of the same myth, they do not have divergent ‘reflections’ on the retrospective opened by the myth and, consequently, on the strategy with which to pursue the ‘goal’ of the suprahumanist tendency.”

EP: In the current debate on the notions of the West and Europe, what place can the thought of Giorgio Locchi take?

PL: You asked for a quote earlier, I’m giving you one as a prelude to my answer: “Europe only exists, and is only possible, when it ceases to be the West of the world. As long as the Europeans do not renounce this logic, any political project will have the effect of nailing them to the historical destiny that stems from Yalta.” Locchi says so in the last of the twelve Definitions brought together in the work which has just appeared, named, following the example of the first Italian edition of the Definizioni: “Europe is not heritage but future mission. If we look more closely, the whole current debate on the notions of the West and Europe can be resolved by adopting this perspective, which is none other, once again, than that of Nietzsche, for that Europe is “Land der Kinder,” land of children and not of fathers, and of Heidegger, when he calls for the “new beginning” of Europe (for example in his first course in the lecture course, Introduction to Metaphysics).

Once again, the distinction between the spherical vision of history, specific to the suprahumanists and the linear, parabolic vision specific to the egalitarians, makes it possible to better understand the distinction between Europe not-heritage-but-mission-future and a Western Europe doomed to disappearance or to the triumph of the annihilation of our civilization.

The fact remains that there is still debate between Europe and the West in the suprahumanist camp. This is due above all to reasons of a semantic order and generally comes from the absence of a possibility of precise expression, because many are still those who feel things in a suprahumanistic way, but remain prisoners of a vocabulary and terms which I hope Locchi’s thought will make it possible to understand to what extent they belong to the opposite tendency. In his study “History and Destiny”, the second of the Definitions, Locchi speaks of a “modern schizophrenic West,” in majority “Judeo-Christian West which ended up discovering itself as such” and where “only the small minorities, scattered here and there, look with nostalgia on the achievements of their oldest ancestors… and dream of resuscitating them”—recalling however that such a return “can never happen” (“we do not bring back the Greeks”), but… can turn into a regeneration of history. And he who says regeneration of history, says regeneration of Europe, uncoupled, therefore, from a now ambiguous and mostly enemy “West.”

The West, with which Europe was certainly able to merge in the past, and to which most of the current leaders of European nations claim to belong, has in fact today become egalitarian and now seems above all to aim for the establishment of a new leveling and populicidal world order. From the Locchian perspective, Europe is opposed to this egalitarian West which no longer has anything to do with the Europe that the suprahumanists are calling for (and it is moreover not without interest to see that more and more, and even within the European Union, a tendency is emerging which, in the name of European sovereignty, opposes the dominant vision which aims to include Europe in the sphere of influence of the United States, rightly perceived as the new center of the West).

EP: How do we apply the “Locchian” reading grid in 2023?

PL: I believe I have already given a certain number of examples, and the last just now. In summary, I would say that with Locchi, any fighter for a new European renaissance has a precious compass allowing them to distinguish, beyond the appearances of a major and complex epoch conflict, what is the responsibility of their own tendency: suprahumanist, within the scope of the opposing egalitarian tendency.