Because of research in the Donbass, journalist Patrik Baab lost a teaching position – now he is suing Kiel University.

For a forthcoming book, the renowned journalist Patrik Baab is analyzing the background to the war in Ukraine. What could be more natural than to go and see the reality? A year after his visit to western Ukraine, he went to the eastern Donbass in the early fall of 2022, which the Ukrainian army has been bombarding since 2014. But anyone who stands up to Western propaganda needs to really be steady on his feet: A media shitstorm, peppered with half-truths and slander, burst upon him; two universities banned him from teaching—and Baab is going to court.

Research in the Donbass

Patrik Baab is an experienced investigative journalist. He has produced numerous reports for North German Public Broadcaster NDR, and other news outlets and books as well. He has passed on his knowledge to students at the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (CAU), among other places, and already had the teaching assignment for this winter semester in his pocket. Baab is also writing a book about the conflict in Ukraine. What was the history of the conflict? What caused the situation to escalate? When, how and what led to Russia’s invasion? What do those affected on the ground think about the developments leading up to the war?

It seems journalistically imperative to approach the complex interrelationships on the ground as objectively as possible. During the semester break, Baab traveled to the Donbass via Russia. The trip, he says, was long planned. A year earlier, he had been researching in western Ukraine. It was a coincidence that he directly witnessed the referendums on annexation to the Russian Federation. Baab filmed in destroyed cities, spoke with those affected, watched the election—good journalism, one would think.

But no one should enter a war zone alone, especially not if they lack perfect knowledge of the language and the place. That’s why Baab had Sergey Filbert at his side, who runs the well-frequented German-Russian YouTube channel Druschba FM. Filbert knows the country, speaks the language, but has been pilloried by the “leading media” for years. But where else could Baab have reported directly from the scene of the events about his observations, which do not always quite fit in with Western propaganda?

Shitstorm and Expulsion

The shitstorm was not long in coming. It caught up with Baab during his trip and probably started with t-online. Author Lars Wienand claimed untruthfully that Baab had traveled to Ukraine as an “election observer,” and other media outlets took this up without checking. Wienand also got in touch with the Hochschule für Medien, Kommunikation und Wirtschaft (HMKW) in Berlin, where Baab taught. Even before Wienand’s article appeared, the School declared its lecturer an outlaw with reference to the yet-to-be-published “article” and banned him from teaching.

Baab’s former employer, NDR, immediately followed suit. The station did not hold back with the personal attacks and obviously used the opportunity to settle old scores. Because Baab was never comfortable there. As early as 2019, he and other colleagues had denounced serious abuses in public broadcasting. Among other things, there were allegations of political influence.

The media campaign also put Kiel University on alert. In a hysterical, moralizing three-liner made up of a string of propaganda terms, the university announced that it would terminate Baab’s teaching contract. A few days later, the university also informed Baab of this in writing, in long form. I have the letter in hand, in fact.

To understand: teaching assignments from state universities are contracts under public law outside the scope of labor and civil service law. Lecturers are thus denied numerous rights of permanent employees, such as collectively agreed salary, allowances, vacation, continued payment in case of illness, and so on. Unions have long criticized this practice.

Nevertheless, universities may not prematurely terminate teaching assignments once they have been granted without good cause, such as a lack of students or violations of the teaching agreement. Private moral attitudes and political views on certain topics are not among the reasons for termination.

And this is as it should be, because freedom of research and teaching, of opinion and of the press, is a basic democratic right, enshrined in Article 5 of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany.

University with a “Clear Stance”

The University of Kiel, however, is just as unconcerned about all this as the HMKW. When it comes to the Ukraine war, the educational institutions display the politically desired, simple friend-foe paradigm, according to which NATO and Ukraine are good and Russians are bad. You don’t talk to the bad guys; you believe everything the good guys say—and anyone who sees things differently gets fired, journalism or not.

In other words, the Kiel University CAU requires its lecturers to adopt a predefined political stance on the Ukraine war, both professionally and privately.

In its letter to Baab, Kiel University revoked his teaching assignment in a highly emotionalized manner. Instead of well-founded evidence for all the cobbled-together accusations, the letter is just a string of evaluations, accusations and personal attacks.

CAU has also apparently cribbed from t-online. The first accusation is that Baab was in the Donbass “during the sham referendums” as a “Western election observer” and, to make matters worse, took part in a press conference with Russian media—without being certified by the United Nations (UN) for this task, as required.

Although Baab clearly stated that he had done research in the Donbass exclusively for his book and that nothing could be heard or read in his work that might be deemed praise of the Russian government, the CAU insisted on its interpretation, even in its negative statement of opposition. It further stated:

“The foregoing conduct is likely to call into question Christian Albrechts University’s unequivocal stance on the war in Ukraine. Your appearance as an ‘observer’ of the sham referenda gives the appearance of legitimacy to Russia’s occupation and annexation of Ukrainian territories in violation of international law.”

The university’s stance is described as follows by the signatories, Christian Martin, Robert Seyfert, and Dirk Nabers, all professors in the fields of politics and sociology: Since CAU is committed to peace, it stands by Ukraine and “strongly supports the consistent action of the German government and the EU sanctions against the aggressor Russia.” It has therefore already suspended student exchanges and scientific cooperation with Russia.

Mind Control Instead of Freedom of Teaching

In other words, because the university is for peace, it has sided with a warring party, namely Ukraine, and thus backed the political views and aspirations of the German government. Criticism of German and EU policies is unwelcome. It demands the same from its lecturers.

The university has obviously mutated into a political-influencer establishment that controls the personal attitudes of its staff and lecturers, in an all-encompassing manner.

The educational institution now fears a “loss of reputation,” as a result of Baab’s research trip. The impression must not be created, it wrote, that some of the lecturers could be in favor of Russia’s behavior. The signatories do not say a word about the task of journalists to do thorough and proper research. They are also silent on the freedom of research, freedom of the press and of opinion.

False Allegations

After an unsuccessful appeal, Patrik Baab is now suing through the Schleswig-Holstein Administrative Court against his expulsion. Lawyer LL.D. Volker Arndt accuses the CAU of several false allegations in the preliminary statement of grounds for the action. His client had neither traveled to Ukraine as an election observer, nor had he allowed himself to be taken over by the Russian regime or relativized the war. Further, he writes:

“The plaintiff, as a journalist committed to reporting on the ground—and not from afar like other media observers—undertook highly risky research in order to actually see and report on the situation on the ground with his journalistic experience.”

Mr. Arndt emphasizes: “In the difficult and dangerous war situation, Baab maintained a critical distance to all sides. He only observed, filmed and spoke with people—and did so in a way that was legitimate under basic and human rights. His presence in eastern Ukraine also did not, as has been alleged, contribute to any advantage for the Russian government. Rather, Baab was fulfilling his journalistic duty of being diligent. The revocation of his teaching assignment was therefore unlawful.”

Political Censor Clique

Baab has also criticized the approach of Kiel University as a whole. It has not granted him any legal hearing so far, he said. “They didn’t talk to me, but simply presented me with a fait accompli,” he said in an interview with me.

In his estimation, his criticism of the NDR plays a major role in the university’s reaction. Baab spoke of an “obvious act of revenge” by a “political media clique” at the executive levels of the public broadcaster, under the guise of investigative research, carried out by economically dependent freelancers. This network extends into the university, he believes.

Meanwhile, the NDR is playing a familiar tune. It accuses Baab above all of having talked to the “wrong people,” who allegedly spread “conspiracy narratives” and are “open to the right.” The media’s largely one-sided handling of the protests against the Covid measures sends its regards. Baab’s journalistic merits in the past go unmentioned. The NDR has declared the disliked person a persona non grata, a street urchin—in other words, outright political censorship with serious personal and social consequences for the person concerned.

University Propagandists

To be very clear: Where even renowned journalists like Patrik Baab have to fear losing their jobs and being publicly discredited for disagreeable reporting, there is no real freedom of the press. In view of this, it is hardly surprising that Germany’s leading media are perceived as being in sync with the rest of the world. Those who only write what the government wants and what the top management dictates are not disseminating information, but propaganda. When even teachers at universities are expected to teach prospective journalists how to think, this situation has long since outlived its usefulness.

On-site research, Baab explains, “is not only part of the journalistic mission, but absolutely necessary for obtaining information.” “It’s a reality check,” he says. It’s the only way, for example, to check governmental pronouncements for their truthfulness.

And you also have to talk to both sides, he says, precisely to avoid being “joined at the hip” to one side. Corresponding accusations by the university against Baab should rather be directed at journalists who reproduce—unchecked—the propaganda of the Ukrainian government and NATO.

The problem of opinion-making in the leading media probably goes deeper. One has to ask: If universities prescribe certain political attitudes to their lecturers, the thought is not too far-fetched: Will budding journalists learn to do objective research at all? Should they perhaps no longer learn this at all, in order to produce certain political opinions instead? At any rate, this would explain the dilemma in the major German media. Whether on the subject of Ukraine or Covid, it doesn’t matter: propaganda disguised as “reporting” is on the rise. And perhaps not least the universities are providing enough new propagandists.

The CAU itself does not want to comment on its mode of expression. Regarding my own questions about all this, it referred me to the current procedure, which Patrik Baab set in motion, and then remained silent. Thus, for the time being, it remains the secret of the CAU as to what legal basis it can at all demand of its staff and lecturers that they express a very specific political stance on the Ukraine conflict, both professionally and privately. Was the scientific community in the same frame of mind in the Covid case?

Susan Bonath writes from Germany, where she studies painting and ceramics. This article appears courtesy of Rubikon.

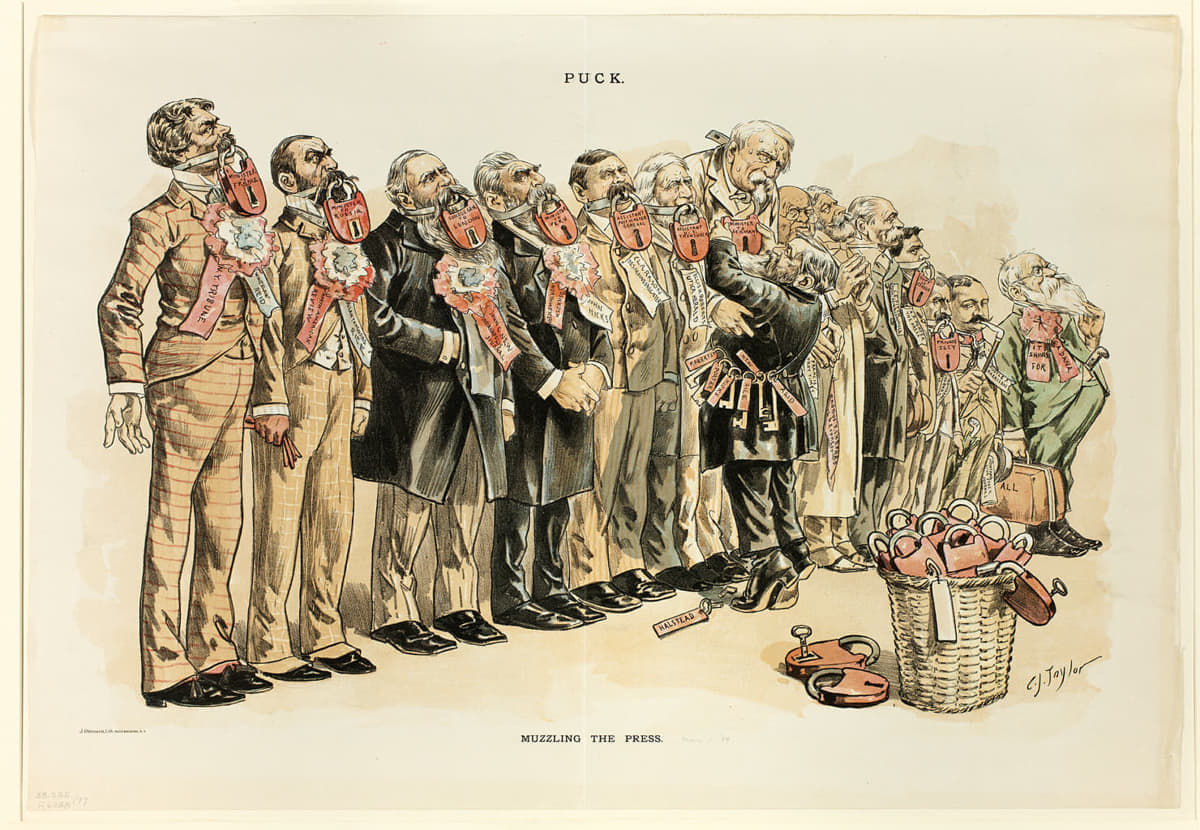

Featured: “Muzzling the Press,” lithograph by Jay C. Taylor and J. Ottmann; published in Puck, May, 1889.