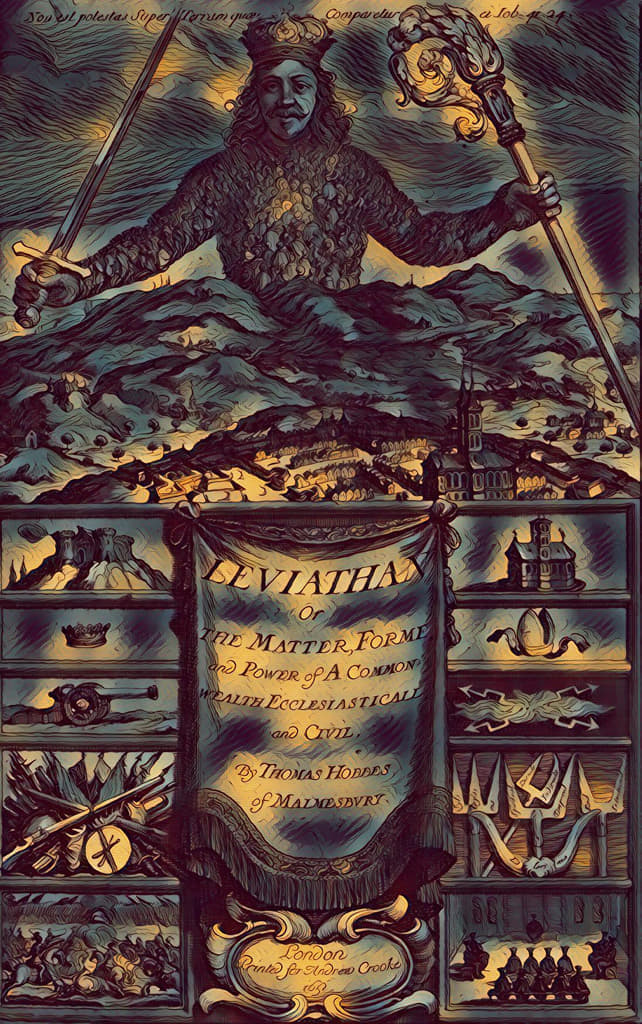

Former director of the Ethics and Law Department at the Research Center of the Saint-Cyr Military Academy, the philosopher Henri Hude has just published, Philosophie de la guerre (Philosophy of War), a book written for decision-makers who, in the tragedy of history, have an urgent need to rise to the level of the universal, in order to appreciate situations objectively, and master them effectively. Faced with the persistent risk of high-intensity war that threatens the world, Hude defends the thesis that the solution to the problem of war does not lie in the power of a planetary empire, a kind of “global Leviathan,” but in a philosophical and spiritual awakening, in which religions are called upon to take an essential place and to cooperate in view of a “cultural peace.”

[This interview was conducted by Guillaume de Prémare of the magazine, Permanences, through whose kind generosity we are able to bring you this English version].

Permanences (P): In the present state of our civilization, what are its weaknesses and strengths in the perspective of a return of the tragedy of History?

Henri Hude (HH): It was Reason that made the fortune of Western civilization. The major weakness of the West today is the loss of strong reason and the sense of truth, if that truth is objective, universal, demonstrative and binding. Human freedom, which also characterizes Western culture, is a power of rational self-determination. If reason weakens, thought becomes delirious, and freedom arbitrary.

The great modern philosophy—Kantian, for example, that held sway under the Third Republic—was idealistic; but while losing reality, it had kept objectivity, that of science and morality. Man was everything. Nature and God were who knows where, but Reason remained an impersonal principle at the core of the human soul, capable in theory of absolute truth and in practice of universal and categorical obligation.

Postmodern thinking has swept all that away. Neither God, nor Nature, nor Reason, nor Being. The individual replaces everything, and facts are only what he wants them to be. Individuals therefore spread the infinite magma of data, giving it through their discourses a form of consensual objects, temporarily consensual. It seems that shared envy and common arbitrariness, in affirmation or negation, will suffice to produce reality, even objectivity. Even science bows before desire and interests. There are only fictions left—but these fictions are also all of reality. Western society thus begins to look very much like an insane asylum. Of course, this is only a collective paranoia: one bomb falls somewhere in our country, and very real realities, which mock our discourses, are destroyed and this philosophy collapses. While waiting for war and defeat, or a revival of rationality, to restore, perhaps, realism, the West lives without foundations and plunges into a kind of blur, into a non-functional culture and a somewhat ungovernable society. The powers that be no longer have any leverage to reform—they are all-powerful to deconstruct, powerless for the rest. Let’s not be surprised that history is becoming tragic again.

P: How do you define the tragic?

HH: The tragic is not evil, it is fatal evil. The tragic is beyond the dramatic, where we still oscillate between fear and hope. The tragic is when there is no way out and we are forced to go through it. We sometimes imagine that tragedy would disappear completely if all problems could find a technical solution. This would be true, if all reality were mechanical. But it is not the case. To believe this is to institute a society in which everyone is treated as a cog in a machine. This is why technology, which solves so many problems, immediately creates other, even more serious ones. It itself becomes an unsolvable problem—through technology. This is what the invention of the atomic bomb clearly shows.

P: This tragedy, which we may have thought we could escape, was very much present in the ancient culture from which we come. Why did the Greeks write so many tragedies?

HH: The Greeks were the first humanists of the West. Aristotle said: “Man is the animal in which there is a lot of the divine.” Humanism guesses the greatness of man. Courage is part of this greatness and expresses the awareness of it.

Heroism is the depth of courage. It is the capacity to measure the tragic without dissolving it, without hiding it. It is the capacity to face death, destiny, freedom, salvation or perdition, and evil in all its forms, including war—that universal phenomenon, in time and space. It is part of human existence.

P: We thought we could overcome war, and some say that we have become somewhat soft. Can a nation and a people adapt and quickly convert their mentality and worldview in a crisis situation?

HH: Experience must answer, more than reasoning. What will happen if we have to switch from a soft dream to a hard reality? For example, if we cut electricity in Paris or Lyon for several weeks, what would happen? If the Internet stops working, how will we react? Will we be able to adapt quickly to a new situation that radically shakes up our daily lives and our gentrified mentalities? No one can know a priori. In Ukraine, which is a more rustic country, it is a return to their youth for the older people, because the memory of very difficult times is still recent and vivid.

Generally speaking, humans are built in such a way that they can cope with all sorts of hazards, but this capacity to adapt—to be resilient, as we say today—depends a great deal on the culture: to adapt to the torment, one must accept the very idea of suffering, so that suffering has a meaning, that life and death have a meaning. I fear that if culture is unable to offer us such a meaning, it is not functional—it does not put man in a position to face the hazards of his condition. There is tragedy. Perhaps we will have to bear our share of it. But if the collective meaning of our existence is reduced to consuming satisfactions and living to be old in almost good health, we will not be able to face it. We escape from this nonsense by recognizing the transcendence of man’s soul and that of the Absolute, of God.

P: This sense of transcendence is not very developed today, to put it mildly.

HH: The great philosophy of the Enlightenment, which—as we have said—still reigned in France under the Third Republic, was a religion of Man. There was no longer any Transcendence in the biblical sense of the word, but there was still one, within the Great Divine Whole that man believed to be between the impersonal universal ground that was Reason and the individuals in which it was, so to speak, always incarnated. And this Reason founded objective truth and moral obligation. This dissolved with what is called postmodernity, coming from Nietzsche or Freud among others.

The great rationalist philosophy was rejected because of its neurotic moralism; also because the evolution of sciences had made it partially obsolete; also because it was very aristocratic, elitist, not very accessible, hardly taking into account the individual, of his lived experiences, of the affective, of language, of the body and finally, perhaps especially, because this residue of transcendence constituted still a source of obligation and a limit to the pretensions of the individual freedom to a boundless independence.

Demolishing God, Nature, Reason, Being, Truth, etc., this postmodern evolution leads in practice to nihilism. Living together in confidence under these conditions becomes almost impossible and society becomes ungovernable. Without a cultural revolution, including the recognition of metaphysical foundations, the West will persevere in this nonsense and it cannot even imagine to what extent it will lose its aura and its position in the world. It is a functional culture that allows a civilization to be present in history and to stay there.

P: The prospect of a philosophical, spiritual and cultural upsurge seems rather distant today. Can a time of crisis make decision-makers arise and/or new leaders emerge who will be able to face the situation, and give meaning to events and involve all citizens?

HH: The great crisis occurs when culture does not allow solutions to be found to problems that have become absolutely vital. The non-functional character of culture is today, in my opinion, the root of all problems. I think that we will have difficulty in seeing the emergence of true decision-makers, without a cultural awakening.

P: Today, the West is still dominant, despite its non-functional culture, but it is fragile for the reasons you indicate. On the other side, there is what we can call the rest of the world, which functions according to very different mental patterns. We have the impression that, for the other civilizations, war and the tragedy of history are quite normal things. Doesn’t this create a gap between the West and these other cultural realities, confirming in a way the famous “clash of civilizations?”

HH: We exaggerate cultural relativism. There is a human universality, a community of human nature: each of us is born, dies, suffers, works, exchanges, loves, speaks, questions, invents, negotiates, wars, is cunning, meditates, is anxious. Every man in existence becomes aware of our common nature; and it is this common awareness which is the culture. In all functional cultures, the fundamentals are present, like friendship or truth. The same questions arise everywhere. Zhu Xi could dialogue with Thomas Aquinas, Socrates with Confucius.

However, the human condition also depends on technical progress. Now, in technology and in science, a whole way of thinking is forged. If this way of thinking does not manage to be in harmony with immemorial wisdom, culture becomes dysfunctional. This does not prevent the sciences from being true, nor the techniques from being efficient. And since the West is the place where science and technology first developed, Westernization is inevitably universal. But as it is the reason which made the fortune of the West, so its unreason deprived of wisdom is making its ruin. For the West is becoming the least rational fragment of the planet. If it does not return to reason and wisdom, we will see, in our lifetime, its marginalization—and its great suffering.

P: All the same, the fundamental principles are not the same in all civilizations; for example the notion of freedom in China, or that of equal dignity of persons in India.

HH: You have to look at things in the long term. The simple fact of owning, for example, an iPhone provides a feeling of individual power that was previously unimaginable. This feeling leads to the emergence of an individualism, which is not necessarily negative and anti-social in itself. Technology allows man to realize his power and nourishes the consciousness of a transcendence of the human being. This phenomenon can be devastating for all premodern cultures, and lead to non-functional ways of thinking, where we no longer understand anything about the Absolute or about God, about life, about the universe, about good and evil, about Salvation… But it can make a civilized humanism grow everywhere. The most reasonable solution is to profoundly rethink the relationship of humanist culture to the religion of the God-Man, that is, of Christ. Otherwise, the West will go out of history. But I believe that all its positive values will survive, carried by other peoples.

P: The Romans, then Christianity, developed the concept of the just war, and the Church tried to moralize war. Are there equivalent reflections in other civilizations?

HH: The Canadian researcher Paul Robinson has written a book entitled Just war in Comparative Perspective, in which he shows that all civilizations have had a similar reflection. It is easy to understand why. On the one hand, everyone realizes that goodness is found in justice, peace, mutual service, good understanding; and that war, which uses violence and trickery, is the opposite of the charity we owe each other.

On the other hand, absolute pacifism, in its pure state, seems equally immoral. For if the use of force were unconditionally immoral, intrinsically perverse, there would be no right of collective self-defense, and surrendering to an intrinsically perverse power would be a duty. Moreover, all non-violent resistance would be physically eliminated. Thus, on the one hand we have the immorality of war, on the other the immorality of pacifism. The theory of the just war is an attempt at a solution. War is evil itself; but one must be ready to defend one’s own against aggression. For it is a fact—conflict exists, not just cooperation. The world is full of transgressors, aggressors and unjust people, who take pleasure in appropriating everything and find their enjoyment in the persecution of others. One must therefore be ready to defend one’s own. This is what every functional culture must teach its members. But this is not possible if we sink into the illusion that everyone can remain quietly in his corner, in a passive individualism.

P: The classical theory of the just war has, however, been challenged by Pope Francis.

HH: I read very carefully the chapter of the encyclical Fratelli tutti that deals with war. Paul VI also said, at the UN, “Never again war!” Surely, you don’t want the Pope to be in favor of war! The text expresses, I believe, a fear of the possibility, once again very serious, of total war, therefore nuclear. In this chapter, which (with all due respect) can be described as rather vague, the only perfectly clear formula, although drowned in pacifist rhetoric, maintains the Thomistic doctrine of the just war. It seems to me, therefore, that the Pope is not changing anything in substance. In previous years, in the face of the terrorist problems of 2015, he had in fact, unlike his predecessors, a much more classical and Thomistic attitude on the question of war. What terrifies us today—for example, the atomic bomb—will be surpassed tomorrow by other, far superior means of destruction. It is in this perspective that the Holy Father’s words in Fratelli tutti are justified.

Today we do not know how to live in peace without the balance of terror. With the postmodern crisis of culture that we are experiencing, it is possible that this balance of terror will give way to what Thérèse Delpech calls the “imbalance of terror.” The preference for life makes deterrence credible; but this principle is itself suspended from the conviction that life has meaning. To wage atomic war is to commit suicide by killing one’s opponent. If suicide becomes possible because culture induces a preference for death, then nuclear war is ultimately possible. The desire for euthanasia manifests a preference for death. La Fontaine said in one of his fables, “Rather suffer than die is the motto of men.” But the postmodern culture is suicidal. It says, “Rather die than suffer.” That is why the Pope is right to draw attention to the fact that deterrence between rational actors is no longer guaranteed within the framework of this culture that the West is spreading throughout the world.

P: What is the basis for an ethics of war?

HH: The basis consists in knowing that the good is peace, and that nothing should be done in war that would give rise to a definitive hatred, making the conflictual relationship irreversible. It is a matter of, for example, not to create a hereditary enemy, but rather to use force in a measured, proportionate way, and to limit the time of the war. The ethics of war is the imperative of peace regulating war.

P: In 1945, was the use of the atomic bomb by the USA against Japan proportionate and morally acceptable?

HH: When the means are extremely debatable, the end justifies the means, if and only if the end is morally necessary, and if this means is rigorously necessary to reach this necessary end. Thus the question is: what was the end pursued by the United States? Was this end necessary? And, if so, was the bombing necessary for that necessary end? These are the principles, expressed as questions. Their application is obviously by nature more contingent and dubious than the principles themselves.

The political goal of the United States was to impose on Japan an unconditional surrender that would allow it to change profoundly, militarily, politically and culturally, and to make it a satellite in its Empire. Such an imperious goal is part of a policy aiming at imposing on mankind the Pax Americana. If one considers this goal to be morally necessary, then, in relation to such a goal, the use of the atomic bomb was certainly a necessary means. The conditions demanded of Japan by the USA were exorbitant, and it was to be expected that Japan would put up a tremendous resistance. The atrocious use of the bomb broke this resistance and certainly spared more lives, American and Japanese, than it sacrificed.

The answer to the question you ask leads back to the answer to a more fundamental question: Is the global hegemony of one state morally and politically necessary for the common good of humankind? If so, then the use of weapons of mass destruction is probably justified, at least objectively. If not, then not. In other words, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are an impressive show of force and decisive action, which are legitimate only if the United States can reasonably pretend to be the universal Empire, to be the universal hegemon bringing peace and a true flourishing civilization. Otherwise, what would have been legitimate would have been a reasonable negotiation in which the loser would have accepted to take his loss, without being totally subjugated. When a head of state judges that an end is necessary and that the means to that end is necessary, it is he who makes that judgment and assumes the ultimate moral responsibility for it—it is he who will be accountable to the Supreme Judge.

P: Today, some people seem to think that a universal empire is better than war. Does this seem justified to you?

HH: The “great game” for empire has always existed. Powers want to ensure their hegemony, out of ambition but also out of fear. Let’s think of Athens and Sparta, or Rome and Carthage. Is building an Empire, ideally building the Empire, a just cause for war? The Empire brings peace after the time of conquest, the Pax Romana for example. But every Empire will end. What chaos follows! Today, would the constitution of a planetary Empire be a just, permitted and necessary end? As the techno-scientific world becomes more and more unified, the idea that some kind of universal political authority could emerge has some logic and appeal. But this does not necessarily mean a world state, led by a universal imperial power. The “function of empire” must be fulfilled. Exploring this question is precisely what my book does.

P: How do you characterize the Leviathan and the peace it proposes to us?

HH: I reflect upon the future, from the probable state of technology, in a century or two. We must imagine that we will be able to colonize the universe. We have to imagine the military technology that goes with it. Today, it is science fiction, but tomorrow? If there has been no cultural revolution, it is highly probable that we will have such a fear of war that we will accept an absolute security tyranny. The Power will have access in real time to the brain and the whole body of each individual to take immediately, on the basis of automated and very fast anticipations, the decisions required for the collective security. The security requirement will become such that freedom will be reduced to nothing. This is what I call the “Leviathan.” People will accept it and want it, because there is apparently no other way; and there will be no other meaning to existence than to keep this miserable meaningless life.

My thesis, which I believe I have demonstrated, is that far from being a guarantee against a possible nuclear war, the advent of the Leviathan, on the contrary, will make it highly possible. It will bring us total war; and that will be the sad end of history. That is why we need another solution, without the Leviathan.

P: You are looking for the solution of a political and cultural peace without the Leviathan.

HH: If we do not take the risk of freedom, we take the risk of the Leviathan. It is a profoundly unstable regime, extremely oligarchic, concentrated, dictatorial. The dictatorship will have to rely on a kind of planetary and omniscient “Stalin,” with the right to life or death on any human being. Let us be sure that utilitarianism can justify everything, even the worst, in the name of the good. This supposes the injection of a culture of powerlessness upon the planetary people. It is necessary to develop egoism in order to kill courage. It is necessary to fear death in order to favor materialism. It is necessary to suppress all morals and laws in order to make the crimes of the Leviathan seem normal. It is necessary to fear everything in order to cling to the Leviathan as the one who will save us.

P: All current transgressions are justified in the name of the good. Western elites do not present themselves as villains who would like tyranny, on the contrary.

HH: I am not thinking only of Western or Westernized elites. I am a philosopher and my book is neither a political position nor a geopolitical interpretation. I think that any leader, both powerful and influential in the world, is tempted by the Leviathan solution. The Leviathan is not necessarily a conscious and assumed project; it is in any case an objective dynamic that unfolds, as long as the culture remains unchanged, and which can in this framework be seen as the lesser evil. If we want to avoid the Leviathan, preserving the pluralism of states is necessary, because it is the only way to ensure the division of powers. It is also the only way to have a basis for social justice and regulation. Of course, states remain rivals, with their various ambitions, their greed too. But these States, because of the danger of the Leviathan, must be able, individually, to renounce the universal Empire, whose concrete figure is the Leviathan, and, collectively, to take on the function of Empire.

P: However, one can imagine a strong resistance of the people to the Leviathan.

HH: In order to resist an excess of power or exploitation, one needs a coil—to reduce this resistance, one needs to break this coil. This is why the Leviathan must reduce the intellectual and moral strength of individuals and peoples to a minimum. It must intoxicate the masses with a “culture of impotence”: all sorts of nonsense, even monstrosities, but it must remain unharmed. Indeed, if the Leviathan’s elite began to believe in the nonsense it inoculated into the people in order to subdue them, the Leviathan would reduce itself to impotence.

For the Leviathan to exist and last, it needs a caste of hard, rational, ruthless, cruel, immoral men at its head, who are in solidarity with each other. But how to believe that beings armed with such a culture and endowed with such a psychic apparatus will be able to live in peace without devouring each other? The Leviathan cannot keep its promises of peace. We therefore need to find a culture of peace and a political system without the Leviathan, allowing a world balance, a kind of planetary civilization which does not fall into the absurdities we know. For this, we must start from what exists. The religions and wisdoms that have lost the initiative in relation to the philosophy of the Enlightenment must take the initiative again, now that the Enlightenment has gone mad.

P: However, religions themselves can cause wars.

HH: Of course, religions can cause war. Men fight for an interest, which can be material or moral, i.e., political and economic, or cultural. God, or the Absolute, being the supreme Good, religion or wisdom is also, by definition, a supreme interest. Why should men fight for oil or a piece of territory, but not for the very meaning of life? The more necessary the goal seems, the more man is theoretically inclined to use all means to reach it.

P: When Cavanaugh says that there are no wars for religious reasons, but that all so-called religious wars have a political, cultural or economic underpinning he seems to be reasoning against reality.

HH: Most wars have three aspects: economic, political and cultural. In the term “cultural,” I include the religious dimension. The so-called “religious wars” therefore always have both political and economic dimensions. When, in the 16th century, the English nobility seized the property of the Church, or when the German princes strengthened their independence in relation to the Germanic Emperor, it was not primarily out of religious sentiment. In spite of this, fighting for a metaphysical good is possible, because it touches on the absolute, an absolute for which men are willing to die. To pose the problem well and to be able to solve it, it is necessary to universalize the notion of war of religions and to speak about wars of cultures. Thus, the wars between ideologies born of the Enlightenment, although they do not have a motive that would normally be qualified as “religious,” are nevertheless battles waged for what seems to have an absolute value. These wars of ideologies have probably caused more deaths than all the religious wars. However, if religions can be a factor of wars, they can also be a factor of peace.

P: How can religions be a factor of peace and also bring part of the solution to the problem of war, and thus spare us the advent of the Leviathan?

HH: If we take into account and respect a factor of personal freedom in adherence to the truth, religion automatically leaves the logic of war. For peace to reign, a formula of equity must be found, a way of sharing power, authority, wealth, territories, natural resources, etc. This is why most of the great wisdoms and religions are capable of making an extremely positive contribution to the definition of a kind of global social pact of equity.

I am not at all sure that the current Western formulas, which are liberal extremisms, can achieve anything other than instituting selfishness and war. It would be absurd to deny the potential or actual frictions between the various wisdoms and religions; for they exist, as between the various modern ideologies. However, a very new fact has appeared—from now on, we see the Leviathan emerging; and we know that, if religions allow themselves the luxury of wars between religions, they will all “die.” Indeed, the Leviathan has two ways to impose itself against religions: to divide them in order to throw them against each other, or to dissolve them in a relativistic syncretism.

P: A kind of universal and humanitarian soft religion?

HH: Yes. Religions will be tolerated if they manufacture impotence; but they will nevertheless remain suspect, under surveillance. The important thing is that they produce power for the Leviathan and powerlessness for the citizens. The situation being what it is, with the Leviathan on the horizon, either religions will show exceptional stupidity and will be dissolved by harshly opposing each other, or they will find what I call “a non-relativistic understanding” based on a culture of philia, excluding armed struggle and discrimination, but not excluding proselytizing and conversions.

P: So, you believe that friendship between religions is possible.

HH: Yes, this philia is the natural law itself, which allows a decent public order. Natural law proposes a system of virtues, a golden rule, universal ethical principles, even if we justify them differently by our metaphysical and religious beliefs. I believe that this can work.

P: This assumes, however, that this culture of philia is shared by the different religions. Do you think, for example, that contemporary Islam, as reaffirmed since the early 1990s, could adhere to this this principle of philia?

HH: There are two options: either we practice this philia without denying ourselves, that is to say, by following our conscience and continuing to seek the Truth; or this philia is a dream, a utopia, and there will be no alternative to the Leviathan. This is my conviction.

P: For the Islamists, the West still represents Christianity, a land to be conquered.

HH: Any intelligent person who opens his eyes knows that the West is no longer Christianity, and that the present Western powers have practically nothing Christian left. As for wanting to conquer seven billion people with 5% of a billion and no up-to-date military technology, this is nonsense. This is what the Egyptian president Al Sissi once said.

P: For religions to cooperate, they would have to recognize a common enemy of sorts.

HH: The Leviathan is obviously this common enemy, which is at once a pure concept, an objective dynamic and a real potential for power. Faced with this enemy, an alliance of non-relativistic religions and wisdoms and of nations, excluding the universal Empire. If to this is added a philosophical progress which takes us out of modernity and postmodernity, but which is at the same time traditional and ultramodern, then yes, at this moment, we can hope to live an era of peace and freedom.

P: So, you include the religious question in what you call, in your book, “cultural peace.” In this perspective, Catholics fear that Christianity is moving from a reasonable humanism to an unreasonable, almost naive humanitarianism, and that interreligious dialogue is accelerating a kind of post-Christian decomposition within Christianity, even within the Catholic Church itself.

HH: If you have faith, if you believe that God is God, that Christ is truly the Son of God, that He is seated at the right hand of the Father, that He will reign in glory, you can perfectly well go to your Buddhist or Muslim neighbor and talk to him. Knowing each other is important, so that we don’t get the wrong idea about each other, without deluding ourselves about others and ourselves. Since we have the choice between surviving together or dying together, we must learn to talk to each other.

Father Bertrand de Margerie, a Jesuit theologian, a very good man whom I knew well, wrote a book entitled, Liberté religieuse et règne du Christ (Religious Freedom and the Reign of Christ). He thought that religious liberty, properly understood, was the best way to establish the reign of Jesus Christ in the future. However, without this freedom, clashes between religions or wisdoms are most likely and the Leviathan will prosper by capitalizing on these conflicts. Yet it is by taking into account the dimension of personal freedom in the religious act that a religion can extract itself from a logic of war.

You will tell me, of course, that this or that religion gives less importance to personal freedom and seems fatalistic. But one should not caricature. You will also find Augustinian texts which will give you the impression that Saint Augustine was a fatalist and that he does not really believe in human freedom because Grace does everything. But the praxis of man shows that he is nevertheless aware of his own will and of a certain capacity for self-determination. This is part of the universal human experience. If you want freedom, and if you want to save your soul and not end up as a slave of the Leviathan, you have to get out of a logic of religious war.

You ask me if I believe that the Leviathan will impose itself. I answer that it has a reasonable chance of success. But I also think that the future is very open. The more the postmodern West loses control of the world with reason, and the more diverse Asia remains, the less chance the Leviathan has in the short and medium term. The problem will undoubtedly arise again in a hundred years, but in very different terms and circumstances.

P: My hypothesis is that the extraordinary technical power on which the Leviathan relies is inseparable from economic reality. It is therefore a techno-market reality, a power of technique and money that exercises a form of tyranny. In this context, what is likely to prevent the triumph of the Leviathan is the collapse of technical civilization, as the collapsologists tell us.

HH: To the question “Will the world destroy itself?” Zhu Xi answered: “Men will one day reach such a degree in the absence of the Way, that they will fight each other, giving rise to a new chaos during which men and other beings will disappear to the very last.” Very dark perspective, but very profound. Technology however is not in itself a monstrosity.

P: In itself no, but we are reaching technical levels that are becoming monstrous.

HH: What is monstrous is not the great power of man, it is the decorrelation between science and philosophy, between technology and spiritual reality. For example, we do not see that the human body is a “body of spirit” and we treat it as if it were only a machine without a soul. It is true that, if this decorrelation persists, the future state of technology, in the next centuries, will be absolutely monstrous. More likely, History will have come to an end, despite the Leviathan’s promise of immortality, and especially because of the Leviathan’s inability to keep his promises. To re-establish the correlation, it will be a Cultural revolution which will not block technology, but will humanize it radically and will make it, paradoxically, infinitely more efficient by avoiding most of its perverse effects. But this is impossible without a return, in grace and in strength, of religions and wisdoms.

P: Nevertheless, there remains the hypothesis of an impossible control. At a certain level of sophistication of technology and the means it offers, notably in terms of absolute control of social life, it can become impossible to resist it by wisdom, by culture and politics. The task is perhaps too complex because the temptations are too powerful to resist.

HH: This is unfortunately possible, but it is always possible to hope with reason, because evil is always self-destructive. The will to power, carried to its paroxysm, wants its own death, which frees us when all seems lost. Like the scorpion that stings itself. A dark future is therefore not at all written, and we can try, with a reasonable hope, which can also be supernatural, with all that is humanly possible, to give back to our world, and particularly to the West, the cradle of modern technology, a culture and a philosophy worthy of the name. A humanized technology, too. A non-reductive, humanistic science. I believe that that is the urgent work, both necessary and possible.