The progressive doxa and ideology make the women’s rights movement in Spain, in the 20th century, a sort of preserve of radical and Marxist feminism. The leading figures, invariably cited by the mainstream media, are the socialists Victoria Kent, Margarita Nelken and Carmen de Burgos y Segui, the Marxist-Leninist-Stalinists Dolores Ibarruri and Matilde Landa, and, to a lesser extent, the anarchist Federica Montseny. Apart from these? Nothing or almost nothing. Even the famous and talented writer, Emilia Pardo Bazán, has been met with embarrassment or hostility on the grounds that she was an aristocrat with conservative or even traditionalist-Carlist convictions. Other examples? Feminists as important as María Espinosa de los Monteros or Consuelo Gómez Ramos, to name but a few, share a similar fate and are even ignored or blacklisted for having been supporters of a conservative Catholic feminism or for having held public office under the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera.

Another significant case is the Republican-Liberal Clara Campoamor. Honored and admired, often referred to as the most prestigious feminist of the 1930s, her biography is nonetheless watered down, if not glossed over, to avoid mentioning her harsh criticism of the Popular Front. But the archetypal example of ideological amnesia is without question that of the lawyer Mercedes Formica. A major architect of women’s emancipation under Franco’s regime, her Jose Antonian and Falangist convictions, affirmed throughout her life, led to her being placed squarely under the radar.

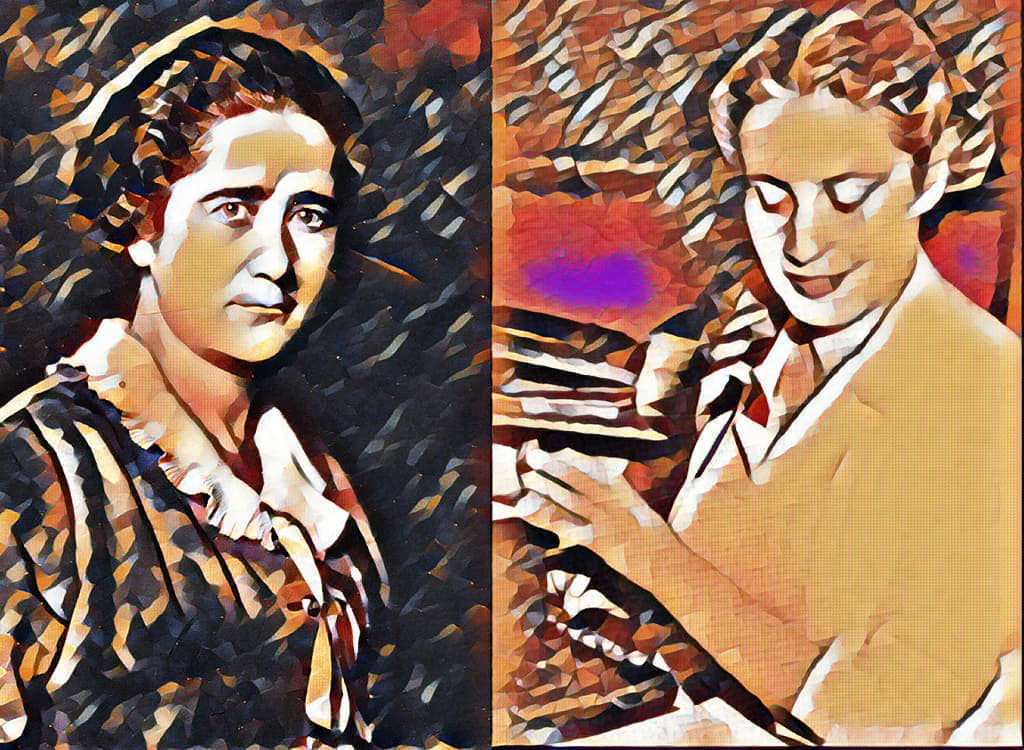

Clara Campoamor Rodriguez and Mercedes Formica-Corsi, are undoubtedly two almost perfect victims of the “historically correct.” One is instrumentalized and manipulated by the politico-cultural power, the other is caricatured, ignored or passed over in silence. They deserve to be rethought, reevaluated and revisited.

Clara Campoamor: A Scandalous Political and Cultural Recovery

Clara Campoamor was born in Madrid on February 12, 1888. While still a child, she lost her father and had to help her mother survive. She was successively a milliner, a commercial employee, a post office employee and a mechanics teacher. She then resumed her studies, entered the University, obtained a law degree and enrolled in the College of Lawyers in Madrid in 1925. A well-known lecturer, she helped found the International Federation of Women Lawyers and the Spanish Women’s League for Peace.

In 1930, at the age of forty-two, on the eve of the proclamation of the Second Republic, Clara Campoamor entered politics. She was a member of the national council of Manuel Azaña’s Acción Republicana, the embryo of the party that he would officially create in 1931. However, she soon left this party to join the Radical Party of Alejandro Lerroux, a centrist party that was then more to the right. On June 28 of the same year, in the general elections, she was elected deputy in a Madrid constituency. A month later, she was appointed by her party as a member of the Commission in charge of drafting the Constitution. She succeeded in having the draft of the fundamental law proclaim the full suffrage rights of women. During the debates in the Cortes, when she defended the wording of the law, she came up against another woman, the radical-socialist deputy Victoria Kent. Like many members of her party, Kent was against the right to vote for women and asked for its postponement, fearing that it would favor the right because of the Catholic convictions of too many Spanish women. A few days earlier, a famous PSOE politician, Margarita Nelken, later affiliated to the PCE, expressed the same opinion in the press. A surprising point of view, but in agreement with that of a good number of socialist-Marxist leaders who, through “elitism”, shared with the reactionary right the same distrust and contempt for the people, who were considered uneducated and had to accept, willingly or not, to be guided by the enlightened elite.

As a result of the successive speeches, including those of Kent and Campoamor, the Parliament was divided into two blocks. Socialist leader Prieto, who also opposed women’s suffrage, left the room before the vote. The final result was clear: 161 votes in favor, 121 against and 188 abstentions. Taking into account that the PSOE had 116 deputies and the Radical Socialist Republican Party had 61, out of a total of 177 socialist deputies, 83 voted in favor and 94 against. 40 percent of those elected to the chamber abstained or were absent.

It was therefore against the will of a majority of left-wing deputies—socialists and socialist radicals (the right-wing deputies were almost absent from this chamber)—that the principle of women’s right to vote was acquired. But, let us emphasize, it was in Spain before France, since French women had to wait for the provisional government of General de Gaulle, in 1944, to become finally electors and eligible as men.

On the occasion of this vote, Clara Campoamor’s intervention was decisive. She has the honor of having been the deputy who contributed most to obtaining the right to vote for women. But it is necessary to remember here an important point; she belonged to the radical party of Lerroux, a republican and liberal party, nourished by anti-Catholic Freemasons, of which she was deputy from 1931 to 1933. She was not a socialist militant or sympathizer, as many leaders and historians of the PSOE say or imply today, trying to appropriate her figure. She expressly rejected Marxist socialism and communism.

Clara Campoamor was also, under the same government, Director General of Beneficiencia y Asistencia Social and delegate to the SDN of the Spanish Republic. She was also one of the main drafters of the law establishing divorce in Spain. And her little known or misunderstood history does not end there. In the aftermath of the socialist uprising of October 1934, against the government of the radical Lerroux, Clara Campoamor, who, it seems, disagreed on the way to repress those responsible for the insurrection, decided to leave the Radical Party. She immediately tried to join the Izquierda Republicana (Manuel Azaña’s party), but was refused admission. The “cardinal sin” that she was accused of, she said, was the women’s vote, which would have led to a victory for the right in the general elections of November 1933. This is at least the interpretation of most of the left-wing leaders of the time, which today is not unanimously accepted by historians. The defeat of the leftists can be explained more by the disappointment of a part of the electorate and the wear and tear of power than by the importance of the female vote.

But the ordeal of Campoamor had only just begun. Too often, it is said and written in an imprecise way that she voluntarily went into exile to escape the horrors of the Spanish Civil War. The unvarnished truth is much less glowing for her opponents. In reality, in September 1936, fearing to be arrested and summarily executed in one or another of the Chekas of Madrid, she fled, with her family, the Popular Front zone, not wanting, as she would later write, “to be one of those details sacrificed unnecessarily.” Having managed to reach Switzerland, via Italy, she published less than a year later in Paris, La Revolución española vista por una republicana (Plon, 1937), an edifying work that curiously was not published in Spain until the early 2000s.

In this book, Clara Campoamor analyzed the origins of the Spanish Civil War and severely denounced the violations of Republican legality by the Popular Front government that emerged from the February 1936 elections. She explained how the situation deteriorated very quickly; how the government, indecisive and inactive, proved incapable of maintaining public order and preventing physical violence and assassinations. She emphasized the extent to which the left, the socialists and the communists, had prepared for war, carefully hiding substantial arsenals of arms and ammunition, and forming and organizing militarily trained militias. She told how from the first days of this fratricidal conflict, leftist terror spread to more and more victims; and how the political persecution spread throughout the Popular Front area.

Clara Campoamor summarized her testimony in “The Causes of the Government’s Weakness, as Seen by a Republican,” an instructive article published after her death in a special issue of the journal Histoire pour tous/History for All (La guerre d’Espagne/The Spanish Civil War, no. 16, February-March 1980, Paris). Here are some brief excerpts to enlighten the reader:

“From the first days of the struggle a bitter terror reigned in Madrid. Public opinion was tempted at first to blame the violence in the cities, and especially in Madrid, on the anarchists. History will one day tell whether they were justly blamed for these events. In any case, it is up to the governments, without distinction, to take responsibility for them.”

“As the exhortations of the government newspapers eloquently show, terror reigned in the rear from the beginning of the struggle. Patrols of militiamen began to make arrests in homes or in the street; wherever they thought they would find enemy elements. The militiamen, outside of all legality, set themselves up as popular judges and followed their arrests with shootings…. The guardians of the law were either indifferent or powerless before the number of executors who carried out this odious task.”

“At the beginning, they targeted the fascist elements. Then the distinction became blurred. People belonging to the right wing were arrested and shot; then their sympathizers; then members of the radical party of Mr. Lerroux, sometimes even—tragic mistake or class vengeance—members of the Republican Left party… When these mistakes were noticed, the murders were blamed on the fascists and continued… The government found every morning sixty, eighty or a hundred dead lying around the city.”

“And yet the government could have stopped the looting and the anarchy, because it had at its disposal the Civil Guard, which, being very numerous in Madrid, did not side with the insurgents. This force, by its numbers and training, would have been sufficient to maintain order in the capital if it had been wanted to be used… The government therefore did not want to use this force which, in order to re-establish order, would have had to repress the violent acts of the militiamen”.

“During the night, Madrid did not sleep, it trembled. Everyone listened attentively to the sounds of the street, strained one’s ears for footsteps on the stairs… always expecting a search by the militia…. Madrid had fallen to the lowest degree of disorganization and bad taste…. But only by hiding under ground could one escape the ferocity of the carnivores of the rear.”

“Of the thousands of prisoners in the central prison in Madrid, only two young men managed to escape. All the others were massacred. Among them were well-known personalities, such as Mr. Melquíades Alvarez, a member of Parliament, a former Republican and leader of the Liberal Democratic Republican Party, and Mr. Rico Avelló, former Minister of the Interior in the government presided over by Mr. Martinez Barrio in 1933, and High Commissioner to Morocco in February 1936. The shooting echoed all night long inside the prison, spreading terror in the neighboring houses.”

“These last facts finally convinced the government to take the leadership of the repression by forming a tribunal, composed of members of the magistracy and a popular jury recruited from all the parties registered in the Popular Front. This tribunal, given the publicity that its verdicts would receive, would be required to measure their scope and justify them. However, it was not afraid to pronounce sentences such as those of Salazar Alonso, Abad Conde and Rafael Guerra del Rio, former ministers of the Radical Party in the Lerroux cabinet, who were accused—without any proof—of having promoted the uprising. Their crime was quite different: it was to belong to the old radical party, under whose government they had been several times ministers.”

“It is all very well to say that in the exasperation provoked by a civil war all these excesses can be explained; but they remain unjustifiable. The peaceful citizens, the humble merchant, the civil servant, the petty bourgeois; in short all those who do not look at life on the historical level but as it is presented day by day, suddenly understood the danger this terror constituted for them, which was exercised by a resentful rabble and envenomed by a hateful class propaganda.”

“Yes, the pay of ten pesetas per day, paid to the militiamen and militia women, the parade in the city, and for some the looting and the revenge, were sufficient baits to attract in the militias many people who should have been in prison…. Debauchery reigned at the front. and many combatants had to be hospitalized.”

“The terrorists worked on behalf of the insurgents more successfully than their own supporters. These elements always forced the government to continue the struggle, and for good reason…. They had the perfect life: provided with money, looting, massacring and satisfying their thirst for revenge and their baser instincts.”

It is understandable that the admirers of the Popular Front boycotted or ignored the honest and severe testimony of this notorious anti-Francoist. Ignored or marginalized by both sides, Campoamor went into exile, first in Switzerland, then, from 1938, in Argentina, before returning to Lausanne in 1955. She lived on her writing and her profession as a lawyer, publishing articles and lecturing at conferences. Her three requests for permission to return permanently to Spain, which were made by visiting her country three times between 1948 and 1955, were all rejected. In 1964, the Tribunal for the Repression of Freemasonry and Communism was abolished, but by that time she had long since given up her plan to return. She died of cancer in Lausanne on April 30, 1972. Her body was cremated and the ashes were deposited in the Polloe cemetery in San Sebastian, in accordance with her last wishes.

Mercedes Formica: An Admired Feminist Turned Pariah

The biography of the lawyer Mercedes Formica is much less known, but it is no less admirable. Mercedes Formica Corsi-Hezode was born on October 8, 1916, in Cadiz, into a relatively wealthy family. Her father, an engineer, was the director of the Gas and Electricity Company of Seville. She was the second daughter of six children who lived their early youth peacefully, without any major problems, between Seville, Cadiz and Cordoba. Her mother, Amalia Hezode, wanted Mercedes to be able to work one day, to be free, independent and to marry for love. She encouraged her daughter to pass the baccalaureate and to study. Mercedes was the only young woman in Seville to enroll in law school in 1932. Unfortunately, that year was a very dark one for her because the family home was destroyed. Her father decided to start a new life with a young German woman. The separation was all the more painful for her mother, who refused the amicable divorce and lost parental authority. Worse still, at the request of her husband and his lawyer, the courts ordered her to move to Madrid with her daughters, one of whom was barely three years old. Amalia would not see her only son again except on rare vacations, barely a few weeks, until her death. The extremely modest alimony she was granted condemned her to live with her daughters in complete destitution. Only scholarships allowed Mercedes to continue her university studies. Divorce law of that time (1932) was favorable to the man; it enshrined the triumph of the stronger, the only one really protected by the law. The marital home was conceived by it as the “husband’s house,” and it gave him the right, humiliating for the woman, to get rid of her by “depositing” her with her parents, in a monastery or in any other place he wished. Mercedes, still a teenager, would never forget the terrible injury and grief inflicted on her mother.

Intelligent, hard-working, charismatic and extremely beautiful, Mercedes Formica became a lawyer, historian, novelist and feminist (although she never liked this last label). Her literary work includes the novels, Monte de Sancha (1950), La ciudad perdida (1951), El secreto (1953), A instancia de parte (1955), La hija de Don Juan de Austria (1972), María Mendoza (1979), La infancia (1987), Collar de ámbar (1989) and the trilogy of her memoirs: Visto y vivido (1982), Escucho el silencio (1984) and Espejo roto y espejuelos (1998). However, despite her undeniable literary talent, it was her political and social commitment that made her famous.

Married in 1937 to Eduardo Llosent Marañon, poet and man of letters, Mercedes Formica rubbed shoulders with all the intellectuals of post-Civil War Madrid. Her husband, Llosent, former director of the magazine Mediodia in Seville, was a friend of poets, such as García Lorca, Gerardo Diego, Rafael Alberti and Dámaso Alonso before the Civil War. He was also known for having contributed to the tribute book, Coronas de sonetos en honor a José Antonio, with the poem “Eternity of José Antonio.” Close to the philosopher Eugenio d’Ors, he was soon appointed director of the National Museum of Modern Art (now Museo Reina Sofia). But the couple’s marriage would only last for a while. After separating, Mercedes Formica obtained an annulment and in 1962 she married José María de Careaga y Urquijo, Mayor of Bilbao and Technical Secretary General of the Ministry of Industry.

Mercedes Formica’s social-political commitment went back to the very beginning of her life as a student. In her memoirs, she recounts that on a visit to a friend’s house one Sunday in October 1933, when she entered the living room, she heard a man’s voice on the radio saying: “We are not a party of the left, which in order to destroy everything, destroys even what is good, nor of the right, which in order to preserve everything, preserves even what is unjust.” This chance “radio” encounter with José Antonio Primo de Rivera, during the broadcast of the founding speech of the Falange, would condition her entire life. Years later, she wrote in Visto y vivido (1982), this “young, intelligent, courageous man was feared, rejected and ridiculed by his own social class, which never forgave him for his constant references to injustice, illiteracy, lack of culture, miserable housing, endemic hunger in rural areas, with no other resources than temporary work, the urgent need for land reform. To confuse José Antonio’s thought with the interests of the extreme right is something that ends up rotting the blood. It was the extreme right that condemned him to civil death, waiting for the physical death that they thought he deserved.”

In Mercedes Formica’s life, the meeting with José Antonio marks a before and after. She would be faithful to his memory and his ideas until her last breath. From 1934, she was resolutely involved in the life of the phalangist movement, not hesitating to put her life in danger. Affiliated with the SEU (Sindicato Español Universitario), she was the only female Phalangist in the Faculty of Law in Madrid. The sympathizers preferred not to join so as not to risk paying with their lives.

That same year, Mercedes Formica was appointed by José Antonio as the female delegate of the SEU in Madrid. When the first SEU National Council met on April 11, 1935, she gave a report in which she insisted on the urgency of creating a Book and Textbook Exchange and on the need to increase the number of scholarships, grants, restaurants and student residences. At the suggestion of Carmen Primo de Rivera, one of José Antonio’s sisters, she agreed to contribute to the activities of the Women’s Section. In February 1936, she became the national delegate of the SEU, and as such a member of the National Committee of the Falange.

After the execution of José Antonio on November 20, 1936, and even more so after the adoption by Franco of the decree-law of April 19, 1937, which imposed the fusion of all movements—Carlists, Phalangists, monarchists and other affiliations—fighting in the national camp, Mercedes Formica felt cheated and disappointed. She was reluctant to remain involved with the new political structure created by Franco, the Traditionalist Falange of the JONS. In 1997, she confided to Rosario Ruiz “Franco was not a Phalangist, and I understood then that all this was going to be a kind of gigantic mess, in which there were many converts who, in order to save themselves, had very cruel ‘merits.’ Before the conflict, José Antonio’s followers were very few, perhaps two thousand in all of Spain, and perhaps even less; and in the Franco zone, only a minority remained, perhaps one hundred or two hundred. Those who were in Madrid and Barcelona were shot.”

She did not hesitate to ridicule last-minute converts, and mockingly asked the question: “But where did so many blue shirts come from?” She reproached the newcomers for having set themselves up “as representatives of something they did not believe in; intolerance being their distinctive sign.”

At the beginning of 1944, the National Delegate of the Women’s Section, Pilar Primo de Rivera, offered her the editorship of the weekly Medina. She also worked for the Institute of Political Studies. In August 1944, she accompanied her husband on a diplomatic and cultural tour of Argentina and met Juan Domingo and Evita Perón. Mercedes Formica lost many years of study due to the Civil War and her involvement in the social activities of the Women’s Section, especially in favor of the children of the defeated. But she finally obtained her terminal degree in 1948. Her first wish was to join the Diplomatic Corps; however, she had to give it up so as not to have to live far from her husband. At the same time, the only woman diplomat in Spain was Margarita Salaverria, who was the first to pass the entrance exam during the Republic, in 1933. Faithful to the national camp, she continued her career under Franco. In the 1970s, her husband was appointed Spanish ambassador to the United States and she lived with her family in Washington.

At the end of the 1940s, Mercedes Formica decided to apply for the public prosecutor’s and notary’s examinations, but again she had to give up quickly because one of the requirements was to be a man. For lack of anything better to do, she joined the Madrid Bar Association. But it was extremely difficult for a woman to join a well-known law firm. Therefore, she opened her own law firm, and also became a journalist, novelist and essayist. In 1951, Pilar Primo de Rivera asked her to participate in the Hispanic-American-Philippine Congress. She was given full freedom to write a report proposing reforms on the status of women. But her paper on the situation of university-educated women in the workplace was eventually deemed too committed and buried. A year later, however, the First National Congress of Justice and Law of the FET de las JONS joined her voice to those of the Phalangists of the Women’s Section who demanded more rights for women.

In 1953, Mercedes Formica was alerted to a news item in the press. It was about the assault of a woman by her husband, who stabbed her several times. When the journalist asked the distressing victim why she had accepted her husband’s abuse for so long, she gave a chilling answer: “I tried to separate from him, but a lawyer I consulted told me that I would lose everything, children, house and my few possessions.” Outraged, Mercedes Formica decided to publicly denounce the absurd law that left separated women without any protection.

On November 7, 1953, she published a famous article in ABC, a liberal-conservative monarchist newspaper, entitled “The Marital Home.” The repercussion was enormous; it was taken up, commented upon, or quoted not only in the national press, but also abroad. In the United States, the New York Times, Time Magazine and Holiday magazine echoed it. The same was true of the European press in Great Britain (The Daily Telegraph and the Morning Herald), Germany, Switzerland and Italy, and of course in the Iberian-American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Cuba). In Spain, this article was praised in the anarchist weekly CNT by the communist activist of the PSUC, Lidia Falcón, future founder of the Feminist Party in 1979 (This famous figure of Spanish radical feminism, would be accused of transphobia and incitement to hatred in 2020 and excluded from the communist party Izquierda Unida (IU), allied to Podemos).

In Madrid, on November 18, 1953, the director of ABC, decided to publish a new article. Its title was unambiguous: “The marital home is not the husband’s house.” At the end of November and the beginning of December, the Madrid daily launched a wide-ranging survey to which the most important Spanish jurists and lawyers were invited. At the 1954 National Congress of Lawyers, lawyer-priests were among those who spoke out in favor of the reform. Some of them did not hesitate to point out that in his 1931 book, La familia según el Derecho natural y cristiano (The Family According to Natural and Christian Law), Cardinal Isidro Goma, the strongest supporter of the “Crusade” in 1936, wrote: “It is time to underline the offensive inequality to which the civil code has relegated the Spanish woman and mother.”

For her part, Mercedes Formica did not stop there. On March 3, 1954, she published an interview in the magazine Teresa, in the Women’s Section, in which she summarized her point of view. Again, on July 10, 1954, she gave a lecture on “The legal situation of Spanish women” at the Medina Circle of the Women’s Section. She did not fight, as one might think, against the retrograde laws of Francoism, but against legal principles dating back to the nineteenth century. The Constitution of the Republic of 1931 stated the general principle that “all Spaniards are equal before the law,” a principle that was taken up by the Fuero de los Espanoles of Franco’s Spain in 1945; but in both cases there were no concrete laws or regulations to implement it. The Civil Code of 1889 had remained unchanged under the Republic, despite the law on marriage and divorce, and then, just as unalterable under Franco’s regime, which had deviated from the law on divorce and introduced penalties and sanctions against abortion, infanticide, adultery and child abandonment. Women needed their husband’s permission for any act with legal consequences. Spain was not an exceptional case; in France, for example, it was only with the law of July 13, 1965 that married women were allowed to work without their husband’s prior authorization and to open a bank account in their own name. On both sides of the Pyrenees, the same prejudice existed in the middle classes—the work of married women was perceived as proof of the man’s inability to provide for his family.

For almost five years, the debates and polemics, initiated by Mercedes Formica, followed one another at a good pace. The lawyer and journalist did not give up. She visited the president of the Supreme Court, José Castán Tobeñas, and obtained his support; she convinced parliamentarians of the Cortes; finally, she had a meeting with the head of state. In order to obtain this meeting, on March 10, 1954, the mediation of Pilar Primo de Rivera was essential. When before the “Generalissimo,” Mercedes Formica mentioned the need for the wife’s consent to dispose of her property during the separation, he corrected her: “No. Consent must be required at all times, with or without separation.” Franco knew from experience the difficulties of children of separated or divorced parents. He remembered that when he was an army cadet and his mother’s alimony payments were late in coming, he was forced to ask for credit at grocery stores. At the end of the hearing, the Caudillo invited Mercedes Formica to go and speak on his behalf to the Minister of Justice, the traditionalist Antonio Iturmendi.

Her efforts were successful, but only four years later. The law of April 24, 1958, would modify sixty-six articles of the Civil Code. The concept of “husband’s house” was replaced by that of “marital home;” the discriminatory concept of “wife’s deposit” was abolished; the man’s absolute power over household goods disappeared; and widowed or remarried women no longer lost parental authority over their children. Mercedes Formica was undoubtedly responsible for this reform of the Civil Code; but it was not until 1978 that the Penal Code was reformed and the discriminatory treatment of women in matters of adultery was repealed. Other legislative reforms aimed at establishing equality between women and men were initiated by Mercedes Formica and her friends in the Women’s Section, such as Monica Plaza and Asunción Olivé. These included the Law of July 22, 1961, on women’s professional and labor rights, and the Law of July 4, 1970, on the consent of mothers for adoption.

In 1970, Mercedes Formica’s signature was among those of 300 writers, some of whom had been volunteers in the Blue Division, artists and intellectuals who protested against clerical censorship to the Minister of Information Manuel Fraga Iribarne. Mercedes Formica intervened again to demand an improvement in the situation of destitute pensioners (1966), to demand an increase in the number of childcare centers (1967), to defend the law decriminalizing adultery (1977), and to denounce the non-application of sentences against rapists (1998). From the 1970s onwards, her work was taken up and extended by the lawyer María Telo (who had a letter-writing relationship with Clara Campoamor) and by Concepción Sierra Ordoñez. Both of them were founders of the Spanish Association of Women Jurists (1971), an association in which the Phalangists of the Women’s Section Belén Landáburu and Carmen Salinas Alonso were also active. These four women were behind the 1975 law on the legal situation of married women and the rights and duties of spouses.

Mercedes Formica’s fight was not only in favor of women, but was part of a larger struggle against injustice and in defense of the weak. It was not, she said in the twilight of her life, an extravagant or senseless struggle, as the opposition (Immobilists) maintained for a while; nor was it a paradoxical, contradictory or even superficial struggle to change nothing in depth, as the extreme feminists claimed. Mercedes Formica wanted to be consistent, in accordance with her youthful convictions, which were against the stereotypical image of the submissive woman, of the angelic housewife, confined to the private space to take care of her husband. She was aware of the reproaches made to the founder of the Phalange for having made comments about women that were described as ambiguous and stereotypical by his opponents. Hadn’t José Antonio said that the Phalange was feminine because it had to have two major virtues, self-abnegation and a sense of sacrifice, which are much more common in women than in men? Didn’t he keep saying that he wanted “a joyful Spain in short skirts?” Didn’t he refuse to plead divorce cases during his life as a lawyer, judging them to be a source of suffering for the children? But to the inevitable scorners and critics, Mercedes Formica answered stoically, as in her Memoirs: “On the anti-feminism of José Antonio and the thesis so widespread, according to which he wanted a woman at home, with almost a broken leg, I must say that it is false. It is part of the process of interpretation to which his thought was subjected. As a good Spaniard he did not like the pedantic, aggressive, extravagant woman, full of hatred for the man. From the beginning he could count on women academics, and he gave them responsibilities. In my particular case, he didn’t see in me the angry suffragette, but the young woman concerned about Spain’s problems, who loved her culture and was trying to make her way in the world of work.”

Mercedes Formica continued her activism into old age. She wrote her last article in 1998, before the first serious symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease affected her. She died in Malaga on April 22, 2002, victim of a heart attack. Very few people attended her funeral and few media reported on her death, even though she was undoubtedly one of the most important women of 20th century Spain. Recognition is not a virtue of the vulgar, it is the prerogative of great hearts, they say. These were not legion at the time of her death. In 2015, at the instigation of the Marxist and far-left party Podemos, the municipality of Cadiz removed the bust of Mercedes Formica that had been installed in the center of the city, in the Plaza del Palillero. But two street names perpetuate her memory to this day, in Malaga and Madrid.

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés.