How are we to analyze the Spanish Civil War, beyond the myths and political passions? How is a historian’s work to be done, given that history is often heated and subject to the passions of memory and partisan politics? Such is the work of Pío Moa in his book on the myths of the Spanish Civil War, which has just been translated into French. The book is prefaced by historian Arnaud Imatz, corresponding member of the Royal Academy of History in Spain, and author of numerous works on the history of Spain. He is here in conversation with Hadrien Desuin. This interview comes through the kind courtesy of Revue Conflits.

Please read our interview with Pío Moa, which we published earlier. Dr. Imatz has also published with us an extensive analysis of Pío Moa’s work, which you will find here and here.

Hadrien Desuin (HD): You wrote the Preface to the French translation of the latest best-selling book by Spanish historian Pío Moa. Is his work rigorous? And if so, why did it provoke controversy in France after an interview in Figaro histoire?

Arnaud Imatz (AI): I wrote the Preface for a number of reasons, both general and particular. The first reason, I believe, is the conception of the history of ideas and facts that was passed on to me by my teachers at a time already long past—the 1970s—when I was preparing my doctoral thesis in political science. My teachers taught me that the quality of historical research (which is not to be confused with historical memory, an emotional and reductive vision of history) depends on the author’s training, his intellectual curiosity, his capacity for discernment, his creativity, his conscience and his moral integrity. They instilled in me the idea that the historian must search ardently for the truth, knowing that he or she will only partially arrive at it. They also convinced me that everything in this regard is a matter of subtlety, proportion, nuance, common sense and honesty.

Having been at first, in a way, a collateral victim of the media lynching suffered by Moa in Spain, it took me years before I decided to overcome my prejudices to read this author who was labeled “inflammatory.” This is a step that the censors of Moa (who are for the most part socialist-Marxist academics in favor of the Popular Front, but also “specialists” eager to get ahead, not to mention the legions of neo-inquisitors who are rampant on social networks today) stubbornly refuse to take—because you don’t make deals with the devil! For my part, I came away, I confess, impressed and astonished by my reading of Moa, and above all with the firm conviction that, unlike many of his critics, he fulfills the criteria of the honest, disinterested historian who has integrity.

I must, of course, mention here my special interest in the Spanish Civil War. This interest has never wavered for almost half a century. It led me first to publish a doctoral thesis on the founder of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, to which the prestigious Spanish economist and academician, Juan Velarde Fuertes, wrote the Preface; and to publish a book with a Preface by Pierre Chaunu, member of the Institute of France (La guerre d’Espagne revisitée, 1989). Then, this led me to write the Preface to one of the best specialists on this topic (unjustly made victim in France of a real omerta for almost forty-five years) the American Stanley Payne (La guerre d’Espagne. L’histoire face à la confusion mémorielle, 2010). Finally, I have written multiple articles on the subject during the years 2000-2020. With all that said, there are of course, among the reasons for my interest, also those that relate specifically to the particular case of Moa’s life and work.

Moa is the bête noire of the left, of the extreme left and of a good part of the right. The hatred and insults to which he is periodically subjected, in journalistic and academic circles, are truly astounding. He is “the incarnation of evil,” a “negationist,” a “dangerous revisionist,” a “fascist,” a “camouflaged Nazi,” a “mediocre author,” a “historian without methodology,” “a pseudo-historian who is not an academic,” “a writer without any insight or culture,” “a provocateur,” “a liar” whose “intellectual indigence is well-known,” and worst of all, a “camouflaged agent of the Franco police.” The adepts of the ad hominem attack have a field day with him. For the most enthusiastic, he is nothing less than an “apologist for the crimes of humanity.” The infamous take-downs, the insults, the invectives and the calumnies—everything was good to silence him in the Peninsula; and the polemics that he arouses today in France, after his interesting and thorough interview in Figaro histoire (summer 2022), can only be a weak echo.

But the Moa question is not as simple as his many detractors would have us believe, who usually confuse, more or less consciously, diatribe with debate. A declared liberal democrat, Moa has repeatedly expressed his respect for and defense of the 1978 Constitution. So, it is really his past and his atypical path—an absolute sacrilege in the eyes of socialist-Marxists and other crypto-Marxists—that he is secretly and invariably reproached for. He was first a communist-Maoist under Franco’s regime. He belonged to the terrorist movement GRAPO, the armed wing of the PCr (the reconstituted Communist Party). He was not an operetta anti-Franco militant, as so many established intellectuals and politicians are today, but an armed and determined resistance fighter, ready to die for his cause. As a Marxist, a fighter against Francoism, an unsuspected leftist, and a librarian at the Ateneo de Madrid, he had access to the documentation of the Pablo Iglesias Socialist Foundation. This research was the main source of his first book, a real media sensation, Los orígenes de la guerra civil Española (The Origins of the Spanish Civil War).

After going through and studying these socialist archives in detail, Moa radically changed his ideas, not hesitating to sacrifice his professional future and social life for them. He discovered the overwhelming responsibility of the Socialist Party and the left in general for the 1934 putsch, and for the origins of the Civil War. Up till then, we used to talk about the “Asturias Strike” or the “Asturias Revolution.” After his book, we talk about the “Socialist Revolution of 1934.” In my Preface, I recounted in detail the amazing story of his first successful book. But it was his bestseller, Los mitos de la guerra civil [The Myths of the Civil War] published in 2003 (reprinted or republished some twenty times, selling more than 300,000 copies, and which was number one in the Spanish sales charts for more than six months) that aroused the truly hallucinatory anger of the mainstream media. Through the voice of the Christian Democrat historian Javier Tussell, the socialist newspaper El País demanded censorship of the unbearable “revisionist.” There were trade unions protested in front of the Cortes, and a hysterical propaganda campaign even suggested imprisonment and re-education of the culprit. Since then, Moa has been persona non grata at state universities and in the public service media.

Thereafter, few independent scholars, academics and historians have dared to take sides with Moa. Some, however, are famous. Among them are Hugh Thomas, José Manuel Cuenca Toribio, Carlos Seco Serrano, César Vidal, José Luis Orella, Jesús Larrazabal, José María Marco, Manuel Alvarez Tardío, Alfonso Bullón de Mendoza, José Andrés Gallego, David Gress, Robert Stradling, Richard Robinson, Sergio Fernández Riquelme, Ricardo de la Cierva, etc. There is also one of the most prestigious specialists, the American Stanley Payne, who wrote these particularly accurate and instructive words:

“Pío Moa’s work is innovative. It introduces fresh air into a vital area of contemporary Spanish historiography, which for too long has been locked into narrow, formal, antiquated, stereotyped monographs, subject to political correctness. Those who disagree with Moa must confront his work seriously. They must demonstrate their disagreement through historical research and rigorous analysis, and stop denouncing his work by way of censorship, silence and diatribe, methods that are more characteristic of fascist Italy and the Soviet Union than of democratic Spain.”

There is another important reason for my interest in the publication of the French version of Pío Moa’s bestseller—the defense of freedom of expression; the fight against all forms of censorship and official truth; the resistance to the rise of totalitarian Manicheism. Pío Moa did not hide his sympathy for Gil Robles, leader of the CEDA (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas) during the Second Republic. A sympathy for the leader of the Spanish liberal conservative party of the 1930s that I do not share; nor do I share Moa’s justification, in my opinion excessive, of the long years of Franco’s dictatorship. It is true that as a Frenchman, I am neither a Francoist nor an anti-Francoist, but a historian of ideas and facts, with a passion for the history of the Hispanic world. But that said, I do not confuse Moa’s research with his political analyses, interpretations and daily commentaries, in which he gives free rein to his combative spirit, his penchant for polemics and his taste for diatribe, inherited, for good or ill, from his past as an insurgent and his solid Marxist training. I agree with him that the Civil War and Franco’s regime are distinct facts that, as such, can be judged and interpreted in very different ways. I also agree with him in denouncing the fundamentally subjective and false reasoning that the Second Republic, which is the founding myth of post-Franco Spanish democracy, was an almost perfect regime in which all of the left-wing parties acted impeccably.

There is a final reason which led me to become directly involved in the publication of Moa’s bestseller. In 2005, Tallandier Editions acquired the rights to Los mitos de la Guerra Civil. The publication of the French version was planned for 2006. A translator was hired, the book and its ISBN number were announced in bookstores. But strangely enough, the release date was postponed; and, finally, the publication was canceled without any explanation. In February 2008, during a program on the French channel Histoire (then directed by Patrick Buisson), dedicated to the Spanish War, in which I participated along with Anne Hidalgo, Éric Zemmour, Bartholomé Bennassar and François Godicheau, I was surprised to learn that another book on the Spanish War had just been published by Tallandier instead. The book was the proceedings of the colloquium, “Passé et actualité de la guerre d’Espagne,”(“Past and present of the Spanish Civil War”), edited by Roger Bourderon, a specialist in the PCF and former editor-in-chief of the Marxist-inspired journal Les Cahiers d’histoire, and preceded by an opening speech by the socialist militant Anne Hidalgo, then first deputy mayor of Paris. It was well after I was made aware of this astonishing experience that I decided to get directly involved in the search for a new publisher. The French-speaking reader would have to wait for fifteen more years to finally have access to this work. We can be sure that the book would not have seen the light of day without the open-mindedness, the independence and the intellectual courage of the management of Éditions l’Artilleur /Toucan.

HD: You yourself are also a specialist of this period. What new contributions does the book make to the historiography of the Spanish Civil War?

AI: It is often said that Moa does not bring anything new, nothing more than what was said before him by authors in favor of the national or “Francoist” camp, such as King Juan Carlos’ first Minister of Culture, Ricardo de la Cierva, or Jesús Larrazabal and Enrique Barco Teruel, or even by anti-Franco authors, such as Gabriel Jackson, Antonio Ramos Oliveira, Claudio Sánchez Albornoz or Gerald Brenan. Perhaps. But none of them ever had the aura of Pío Moa in public opinion. On the other hand, we must distinguish his research work [with his first books, the well-sourced and documented trilogy, Los origins de la Guerra Civil, Los personajes de la República vistos por ellos mismos and El derrumbe de la Republica y la Guerra Civil] from his successful synthesizing effort, which is The Myths of the Spanish War.

But the most innovative element of his work, the one that did not fail to make his opponents cringe, is the disclosure of the archives of the Socialist Party, a party that was totally Bolshevized from the end of 1933, and that was in the main responsible for the 1934 putsch. Many authors had had the same intuition before Moa. The anti-Francoist Salvador de Madariaga had even written: “With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936.” And these harsh words were corroborated by the Founding Fathers of the Republic, Marañon, Ortega y Gasset and Perez de Ayala, and even by the Basque philosopher Unamuno. It was also known that Largo Caballero, the main socialist leader, nicknamed the “Spanish Lenin” by the Socialist Youth (which merged with the Communist Youth in the spring of 1936), had declared: “We do not differ in any way from the Communists… The main thing, the conquest of power, cannot be done through bourgeois democracy… Elections are only a stage in the conquest of power and their result is only accepted with the benefit of an inventory… if the Right wins we will have to go to civil war.” Or again (and note carefully): “When the Popular Front collapses, as it undoubtedly will, the triumph of the proletariat will be indisputable. We will then establish the dictatorship of the proletariat.”

And now, after the systematic exploration and public disclosure of the archives of the Pablo Iglesias Socialist Foundation by Moa in 1999, there is no room for doubt.

HD: Franco is portrayed as entering the war almost against his will. Isn’t that a bit exaggerated? Do the communists have a monopoly on the historical responsibility for the war?

AI: The three main people responsible for the Spanish war were, in order, the socialist leader Largo Caballero and presidents Azaña and Alcala-Zamora, who would later use terrible words to describe the Popular Front. For a long time, at least until the beginning of July 1936, Franco was the general who rejected the idea of a coup d’état. It seems that the assassination of one of the leaders of the right, Calvo Sotelo, was the determining event in Franco’s final decision to participate. The role of the communists, which later became essential, was relatively marginal on the eve of the uprising. Moa’s thesis about the background and course of the Civil War is broadly correct. The main parties and leaders of the left, supposedly defenders of the Republic, violated republican legality in 1934. They then planned a civil war throughout Spain. They then finished destroying the Republic in the fraudulent elections of February 1936, crushing freedom as soon as they took power. I refer you here to the essential work of Roberto Villa García and Manuel Álvarez, 1936: Fraude y violencia en las elecciones del Frente popular, 2019 [On the Fraud and Violence of the Popular Front in the February 1936 Elections]— without the 50 seats that the right was robbed of in a real parliamentary coup d’état, the left would never have been able to govern alone.

The Civil War was not a battle of the democrats against the fascists, any more than it was a battle of the reds against the defenders of Christianity. There were in fact three unequal forces in the Republican camp, or rather the Popular Front. The first, by far the most important, included the communists, the Trotskyites, the Bolshevik socialists and the anarchists, who aspired to establish a people’s democracy-type regime on the Soviet and/or anarchist collectivist model. The second, the nationalist-separatists (Catalans, Basques, Galicians, etc.). Finally, the third, which was much more of a minority, brought together the parties of the bourgeois-Jacobin or social-democratic left, which voluntarily or involuntarily played into the hands of the first force. It cannot be overemphasized that the French Popular Front was very moderate in comparison with the Spanish Popular Front, a left-wing coalition dominated on the eve of the uprising by an extremist, violent, putschist and revolutionary Bolshevik Socialist Party.

In the other camp, the national and not nationalist camp, as the French media repeated out of ignorance or Pavlovian reflex, there were also several political tendencies ranging from centrist-radicals (a group of whose former ministers were executed by the Popular Front), to republican-democrats, agrarians, liberals and conservatives, to liberal monarchists, monarchist-Carlists/traditionalists, phalangists and nationalists. The conflict was between left-wing “totalitarians” and right-wing “authoritarians,” and the true democrats were conspicuous by their absence on both sides.

HD: The Vox movement tries to defend the positive aspects of Franco’s legacy and Moa’s book sells very well. Is Spain rehabilitating Franco? Is it ready to look at its history with objectivity?

AI: The positive and negative aspects of Franco’s regime are known to historians. Among the errors that can be blamed on the Caudillo and the supporters of Franco’s regime are in particular: the drastic censorship applied until the early 1960s, the harshness of the repression in the immediate post-civil war period (not the 100,000 or even 200,000 executed according to the propaganda of the Comintern, but 14,000 judicially executed and almost 5,000 extrajudicial settlements of accounts or political assassinations), and the Caudillo’s unyielding will to remain in power until the end.

The Vox movement, generally described as populist, although in reality it is a pro-European liberal-conservative party, is in fact the only party that currently attempts to defend the positive aspects of Francoism. These positive aspects include the indisputable economic successes between 1961 and 1975 (the years of the “Spanish miracle,” with a GDP growth that oscillated between 3.5% and 12.8%, which allowed Spain to rise to 9th place among industrialized nations, whereas today it is in 14th place); the fact that Franco and the Francoists defeated communism (which was in the minority at the beginning of the Civil War, compared with the Socialist party that was completely Bolshevized, but became hegemonic during the conflict); that they also allowed Spain (which was neutral at first and then non-belligerent) to escape the Second World War; and, finally, that they stopped separatism and preserved the unity of the country. It was the moderate Francoist right that took the initiative to establish democracy; the left having had the political intelligence to adapt and help consolidate democracy.

There are not 36 ways to get out of a civil war; there is only one: total and unconditional amnesty. The actors of the democratic transition (1975-1986) knew this. That is why the Democratic Cortes (in which la Pasionaria, Santiago Carrillo and Rafael Alberti, to name but a few, sat) passed an amnesty law on October 15, 1977, for all political crimes and terrorist acts of both the right and the left (especially those of ETA and the extreme left).

The vast majority of the political class was motivated by two principles: mutual forgiveness and dialogue between government and opposition. It was not a question of imposing silence on historians and journalists, but of allowing them to debate freely among themselves, while being careful not to use their work for political purposes. Since then, a lot of water has passed under the bridge. Memorial laws (Zapatero’s “Law of Historical Memory” in 2007 and the imminent project of a “Law of Democratic Memory” by Pedro Sánchez’s coalition—PSOE-PSC, Podemos/CatComú, PCE/IU—in 2022), were theoretically adopted to fight against “the apology of Francoism, violence and hatred;” but in reality, being totalitarian in nature, they are practically liberticidal. The Spanish authorities seem to want to seek social peace only through division, agitation, provocation, resentment and hatred. Spain is far from trying to heal its wounds once and for all and to look at its history with honesty, rigor and objectivity. Through the fault of its political caste, singularly mediocre, sectarian and irresponsible, it is reactivating the spirit of civil war and is slowly but inexorably sinking into a global economic, political, cultural, demographic and moral crisis of alarming proportions.

Historians know that in history there are facts, sometimes hidden, often underestimated or overestimated, depending on the authors; and that their analyses and interpretations are no less different, according to the convictions and sensibilities of each. But historians also know that no one can monopolize the word and make terroristic use of the so-called “scientific” argument without being outside the space of serious research and ultimately of democracy. Pío Moa knows and proclaims all of this; and for this reason we cannot recommend too highly the reading of his fine, well-argued, courageous and caustic book.

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés.

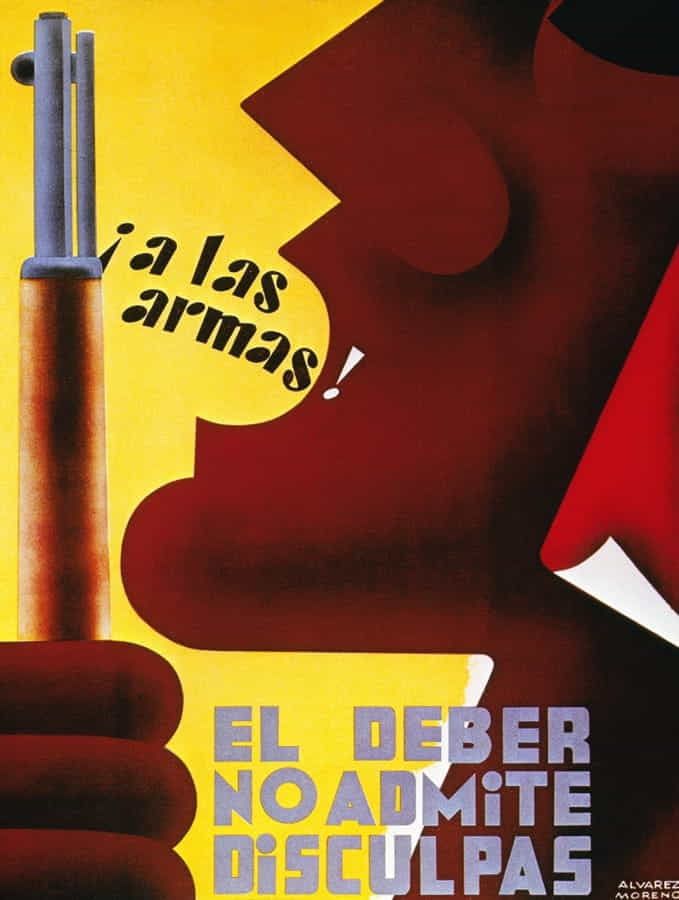

Featured: “To arms! Duty allows no excuses.” Poster from 1937.