To complete this introduction to Moa’s work, a brief historiographical perspective is necessary. History has always been, often partially and sometimes totally, under the influence of political uses or has even been instrumentalized by politics. The border between “scientific” or scholarly history and militant history is very blurred. As a result, the work of independent historians, resistant to conventionalism, is important, necessary and praiseworthy.

The Republic and the Civil War: Eight Decades of Historiography

In order to evaluate the whole historiography of the Spanish Civil War, we can say that it produced mostly militant, and a few scientific, works. In the immediate post-war period, both in Spain and abroad, authors gave in to the temptation of partisan history. For “Francoist” authors, the nation was attacked by anti-Spanish forces. The army, fractures within which they do not mention, was the guarantor of “Western civilization,” the spearhead of the anti-communist “crusade.” Exiled “republican” historians, on the other hand, saw the Civil War as a confrontation between “fascism” and “democracy,” a “classist” struggle, a fight of the poor against the rich, an aggression of the army, the Church, the banks and a handful of fascists against the Spanish people (the communist vision), or a collectivist revolution against reactionary capitalism (the anarchist vision). Others focused on the Civil War as one of national liberation, against foreign imperialism (sometimes Soviet, sometimes Italian-German), and saw it as a prelude to the Second World War. So many simplistic and reductionist theses presented in a caricatured manner.

In France, for seven decades, the works published on the subject were almost unanimously favorable to the Popular Front. Based on the testimonies, articles, books and memoirs of left-wing and far-left leaders (Prieto, Largo Caballero, Álvarez del Vayo, Azaña, etc.), they were, in a way, the counterpart of the writings of the participants or sympathizers of the Franco camp in the immediate post-war period, such as Joaquín Arrarás (a monarchist close to Acción española) or Robert Brasillach (a monarchist close to Action française, who later moved towards fascism). [The book by brothers-in-law Robert Brasillach and Maurice Bardèche, Histoire de la guerre d’Espagne (History of the Spanish Civil War), published in 1939, is a book of reportage, written “in the heat of the action” whose interest is more literary than historical.]

This is all the more explicable, given that the hold of the militants and socialo-marxist sympathizers on French cultural life was major, even exceptional, until the fall of the Berlin wall. First, that of the orthodox communists (themselves often manipulated by Soviet agents); then, that of the various post-1968 leftist trends. [See, Stephen Koch, Double Lives: Stalin, Willi Münzenberg, and the Seduction of the Intellectuals, and Bruno Riondel, L’effroyable vérité. Communisme, un siècle de tragédies et de complicités.] Marxists and crypto-Marxists occupied a dominant, if not hegemonic, position in the French university; they supervised and shut down debate. Hannah Arendt, aware of what was at stake, deplored the fact that the people most easily bribed, terrified and subjugated were the intellectuals. To make a career in the world of French letters or academia, and not be marginalized too quickly, it was necessary to give pledges to Marxist thought, or at least to carefully avoid colliding head-on with the powerful guardians of the “camp of the good.” The benevolence, indulgence, connivance and complicity of a large part of the French and Western cultural and media circles towards Marxist socialism and communist abominations are part of a tradition that goes back over a century. The polemics surrounding the names of Gide, Souvarine, Krivitsky, Kravchenko, Koestler, Orwell, Solzhenitsyn, Bourdarel, Battisti, etc., not to mention those concerning The Black Book of Communism, are a sad illustration.

Sympathy for the Popular Front has always been clearly displayed by French Hispanist academics. Exiled “republican” activists, or their descendants, have also been numerous in national education. Thus, the Society of French Hispanists, created in 1962, was born of the express will of “anti-Franco” professors, militants or sympathizers of the communist-Stalinist, Trotskyist, socialist, social-democrat, anarchist and liberal-Jacobin lefts. We must cite here the example of the communist Manuel Tuñon de Lara, appointed—or rather “appointed” without competition—professor of Spanish history and literature at the University of Pau, in 1965. Director of the Hispanic Research Center since 1970, his influence on French Hispanists has been considerable.

In the 1960s, while the vast majority of writers gave in to the temptation of partisan history, only a few historians from the Anglo-Saxon realm developed a first real effort at critical and objective synthesis. Two of their works translated into French have withstood the ravages of time. The first is Hugh Thomas’s The Spanish Civil War, which has been revised in successive editions, as the author evolved from pro-Largo Caballero socialism, to Thatcherite neo-liberalism through a marked sympathy for Jacobin liberal Azaña. The second is The Grand Camouflage, by Burnett Bolloten, a former war correspondent in the Republican zone. The publication of this book, essential for the understanding of the internal struggles in the Republican camp and very severe on the Communists, was delayed in France until 1977. It passed almost unnoticed because of the hostility of the Marxist intelligentsia and the crypto-Marxist. Moreover, none of the many authors belonging to the Anglo-Saxon historiographical tradition favorable to the Popular Front (Raymond Carr, Gabriel Jackson, Edward Malefakis, Herbert Southworth, Gordon Thomas, Max Morgan-Witts, Anthony Beevor, Paul Preston, etc.) never succeeded, really, in breaking out of the sphere of “specialists” and becoming better known among the general public.

In fact, apart from Manuel Tuñon de Lara, the only historians, for a long time quoted and accepted in the French University, were the communist Pierre Vilar (vice-president of the France-Cuba Association) and the Trotskyists Pierre Broué and Émile Temime. [On the same social-marxist side, we should mention the works of Pierre Becarud, Jacques Delperrié de Bayac, Max Gallo, Maryse Bertrand de Muñoz, Elena Ribera de la Souchère, Carlos Serrano and François Godicheau, without forgetting the memories of the communist, Jean Ortiz.]

Over the years, the majority of French socialist circles accepted the relationship with capitalism or the market economy, but the closed group of Hispanists, specializing in the Civil War, remained subject to cultural Marxism. The semi-militant or semi-scientific works of these authors, openly hostile to any dialogue with the representatives of the so-called “right-wing, reactionary or fascist” history, sank, for the most part, into repetition, conventionalism, collusion and complicity. Jealous guardians of their professional “querencia,” these historians were strangely reluctant to promote the translation of the works of their Spanish colleagues who share the same convictions. [Authors such as Santos Juliá, Francisco Espinosa, Alberto Ruiz Tapia, Enrique Moradiellos, Juan Pablo Fusi, Ángel Viñas, Javier Tusell, and many others, remain unknown in France, outside of a few restricted circles.]

During the years 1980-2010, the Spanish Civil War was the subject of several colloquia, organized or sponsored by universities, including those of Perpignan (1989), Clermont Ferrand (2005), Nantes (2006) and Paris (2006), which were organized always with the unconfessed desire to keep it within the confines of the “other” and leave it as a subject of opprobrium and shame. [The great French Hispanist, Pierre Chaunu, author of Séville et l’Atlantique (Seville and the Atlantic), 12 vols., 1955-1960, wryly made the comment, and not without lucidity, about the “lobby of French Hispanists” (Various conversations with Arnaud Imatz in 1990-1993)].

The few renowned French historians or writers who were in favor of the Popular Front, and who tried to approach objectivity with some success (without claiming total impartiality), were Guy Hermet, Bartolomé Bennassar and the “heterodox” Spain-lover Michel del Castillo. It was an unusual attitude which, of course, earned them criticism from several colleagues more inclined to militant history.

Two other historians and journalists deserve special mention for their attempts at neutrality: Jean Descola and Philippe Nourry. [On the side favorable to the national camp, we must mention more recently, Sylvain Roussillon, Christophe Dolbeau and Michel Festivi.]

It goes without saying that all the works of Spanish authors who sympathized with one or another of the tendencies of the national camp (liberal, radical, republican-agrarian, conservative, monarchist-liberal or monarchist-carlist, nationalist or phalangist) have been systematically ignored, despised or violently criticized. This has been especially true of the work of the former minister of King Juan Carlos, Ricardo de la Cierva, and the brothers Ramón and Jesús María Salas Larrazábal. In 1989 and 1993, thanks to the help and encouragement of the historian of the Institut de France, Pierre Chaunu, I was able to publish La guerre d’Espagne revisitée (The Spanish War Revisited). Much later, after no less than forty years of omerta in France, the historian Stanley Payne succeeded in publishing La guerre d’Espagne. L’histoire face à la confusion mémorielle (2010), which I had the honor of prefacing and which was undoubtedly the first important breach in the dike of “historical correctness.” A decade would have to pass before Pío Moa’s Les mythes de la guerre d’Espagne (The Myths of the Spanish Civil War) was finally published in France.

The End of the Spirit of the Democratic Transition imposed by the PSOE and the extreme Left

To finish explaining Pío Moa’s contribution to the revolt, “revolution” or “change of the historiographic paradigm” of the historians of the “Spanish Civil War” at the turn of the twenty-first century, a final perspective is necessary. Indeed, it must be emphasized that his work is above all a form of resistance to the abandonment of the spirit of the democratic transition, deliberately desired and driven by the radical tendency of the PSOE and its far-left allies.

After the death of the Caudillo in 1975 and up until 1982-1986, two principles animated the “spirit of the Democratic Transition”: mutual forgiveness and consultation between government and opposition. It was not about forgetting the past, as is often claimed today, but about overcoming it. It was not a matter of imposing silence on historians and journalists, but of letting them debate freely among themselves. In other words, all kinds of research, studies, articles and books about the Civil War could be published. But the leaders of the major parties agreed that in political life no one would use or instrumentalize all these works for partisan purposes. Spain was considered at that time the “historic,” “unique,” almost perfect example of peaceful transition from authoritarian rule to liberal democracy, the model unanimously praised by the international press. It was inconceivable that politicians of the right or the left would insult each other by calling each other “red” or “fascist.” Since then, a lot of water has passed under the bridge.

It should be noted that this democratic transition began shortly before Franco’s death. The facts speak for themselves: The decree-law authorizing political associations was enacted by the Caudillo in 1974. The political reform law was passed by the former “Francoist” Cortes on November 18, 1976, and ratified by popular referendum on December 15, 1976. The amnesty law was passed by the new “democratic” Cortes on October 15, 1977. It did not seek to “amnesty Franco’s crimes,” but all political crimes and terrorist acts, including those of ETA and far-left revolutionary groups. Significantly, this law, so contested today by the left, had the support of almost the entire political class (especially the leaders of the PSOE and PCE). It was overwhelmingly approved by the Congress of Deputies (a total of 296 votes in favor, 2 against, one null and 18 abstentions, those of the Popular Alliance, a conservative party further to the right than the UCD of Adolfo Suarez, then president of the government). Let us not forget either the presence in this Cortes of exiled personalities of the extreme left as representative as Santiago Carrillo, Dolores Ibarruri (the Pasionaria) or Rafael Alberti. Finally, it was this same Congress that adopted the current Constitution, ratified by referendum on December 6, 1978 (with 87% of votes in favor).

The first hardening of partisan polemics occurred in the 1990s. The socialist party’s attitude changed significantly during the 1993 election campaign. But the real break came three years later, in 1996, when the PSOE and its leader Felipe González (who had been in power for 14 years and was struggling in the polls) deliberately played the fear card, denouncing the neoliberal and conservative Popular Party (PP) as an aggressive, reactionary, threatening party, a direct descendant of Franco and fascism.

During the 1990s, a veritable cultural tidal wave of neo-socialism and post-Marxism swept the country. The many pro-People’s Front authors flooded the bookstores, occupied university chairs, monopolized mainstream media, and largely won the historiographical battle. The nation, the family, and religion once again became the preferred targets of propaganda. The Manichean history of the first years of Francoism, which was thought to be definitively buried, resurfaced in a different form and under a different guise.

Paradoxically, this situation continued under the right-wing governments of José Maria Aznar (1996-2004). Obsessed with the economy (“Spain is doing well!”), Aznar lost interest in cultural issues; better, he sought to give ideological pledges to the left. Many of his right-wing voters agreed with him, when he paid tribute to the International Brigades (although 90% of them were communists, recruited by the Comintern; and their main fighters fed the security forces and corps of the People’s Democracies, modelled on the NKVD).

[The international brigadists, who had been recruited by the PCF on Stalin’s orders, were recognized in France as veterans by the will of President Chirac (1996). But the idyllic image they enjoy in France is not the same as in Eastern Europe. In the People’s Democracies, they were among those most responsible for the repression of anti-communist opposition. In the GDR, Wilhem Zaisser, aka, “General Gomez” commander of the XIIIth International Brigade, was the first Minister of State Security (Stasi). His deputy, General Erich Mielke, an ex-brigadist and NKVD agent, headed the Stasi from 1957 to 1989. Friedrich Dickel was Minister of the Interior until the fall of the Berlin Wall. General Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, political commissar of the XIth International Brigade, was Minister of Defense. In Poland, the veterans of the XIII Dabrowski Brigade were infamous. Karol Swierczewski, aka, “General Walter” was Minister of Defense; Grzegorz Korczynski Deputy Minister of Security; Mendel Kossoj, Chief of Military Intelligence. In Hungary, Erno Gerö /Ernst Singer, known in Spain as “Pedro Rodriguez Sanz,” head of the NKVD in Catalonia, was the main person responsible for the elimination of Andreu Nin and the POUM; Laszlo Rajk, commissioner of the Rakosi Battalion of the XIII International Brigade was Minister of the Interior; András Tömpe was the founder of the Hungarian political police; Ferenc Münnich, commander of the XI International Brigade, was chief of police in Budapest and later minister. In Albania, Mehmet Shehu, was president of the Council of Ministers. In Bulgaria, Karlo Lukanov was Deputy Prime Minister, etc.]

The same people and voters approved of Aznar’s condemnation of Franco’s regime and the uprising of July 18, 1936 (even though he was the son of a Falangist and had been an avowed admirer of José Antonio in his youth; or in other words, a militant of the independent and dissident Falange opposed to Franco’s movement). The majority of the Right finally acquiesced when he praised the minister and president of the Popular Front, Manuel Azaña, a Freemason and fiercely anti-Catholic, who was one of the three main culprits in the final disaster of the Republic and the outbreak of the Civil War, together with the centrist Republican Niceto Alcalá-Zamora and the socialist Francisco Largo Caballero, the “Spanish Lenin.” Regularly accused of being the heirs of Francoism and fascism, the PP leaders, believed they could disarm their opponents by means of frequent anti-Franco professions of faith.

In 2004, after coming to power, the socialist José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero, an avowed friend of the dictators Fidel Castro and Nicolas Maduro, significantly rekindled the ideological and cultural battle, rather than helping to erase the resentments. Breaking with the moderation of the socialist Felipe González, he chose to reopen the wounds of the past and foment social unrest. In 2006, with the help of the Maltese Labour MP Leo Brincat, he had the Standing Committee, acting on behalf of the Council of Europe Assembly, adopt a recommendation on “the need to condemn Francoism at the international level.” At the end of the same year, various associations “for the recovery of memory” filed complaints with the Investigating Judge of the National Court, Baltasar Garzón. They claimed to denounce a “systematic plan” of Franco to “the physical elimination of the adversary,” “deserving the legal qualification of genocide and crime against humanity.” Garzón, a judge with socialist sensibilities, declared himself competent; but he was disowned by his peers and finally sentenced to ten years of professional “disqualification” for prevarication by the Supreme Court. In view of the attitude of Garzón and his friends, the former deputy and president of the Autonomous Community of Madrid, Joaquín Leguina, one of the historical figures of Spanish democratic socialism most representative of the spirit of the Transition, concluded: “The message that the judge and his hooligans have managed to stitch together is so negative for the Spanish people that it is sinister. In fact, this unfortunate case has sown the idea that in thirty years of democracy the Spanish people have been unable to overcome the past, that the Transition has been cowardice, that the civil war is a taboo subject and that a good part of the right wing continues to be Francoist. A web of lies.” [El Adanismo, Blog of Joaquín Leguina, 20 avril 2010.]

For more than thirty years, the theme of Franco’s repression has been at the center of the thinking of a good number of Spanish historians and academics. Their obsession is to show that the violence of the national camp was organized, that it obeyed a coherent political project, as opposed to a more limited republican violence from below, the result of the disintegration of the state. [Thus, Preston and Reig Tapia try to demonstrate that the war-rhetoric of the national camp explains an alleged holocaust or genocide of Popular Front militants. As the historian José Andrés-Gallego has shown, express incitements to annihilation and texts calling for respect for the life of the enemy abound in sources from both zones. In addition to the interventions in favor of peace by Azaña or Prieto (but never by Largo Caballero, Ángel Galarza, García Oliver or Juan Negrín), in the national camp we can cite those of Manuel Hedilla, Juan Yagüe, Monsignor Olaechea, Cardinal Gomá or Father Huidobro.]

The analyses of such historians always focus on the same points: the negligible violence during the Republic, the massive repression during the war and the Franco dictatorship, the essentially repressive nature of the regime, the false controversy about “Moscow gold,” the powerful Italian-German intervention, the beneficial action of the international brigades, the imposture of the story about the siege of the Alcazar, the role of the “progressive forces” in the democratization, etc. Such are the questions eternally rehashed by them for lack of a relatively balanced history of the Civil War. The only real difference, since the turn of the century, is the hardening of the historiographic divide and the polemical tone of these authors.

[Socialist historians like Viñas and Moradiellos have tried to demonstrate that the government of the Republic and Juan Negrín had no other option than to deliver the gold reserves of the Bank of Spain to Stalin and that they were not in the hands of Moscow. But this is not the opinion of the anarchist historian Francisco Olaya Morales, nor of the socialist Luis Araquistáín, nor of the historians Pablo Martín Aceña or Gerald Howson, and even less so of the historians in favor of the national camp.

The facts about the siege of the Alcázar have always been more or less disputed by historiography favorable to the Frente Popular. The first critical version was devised by the American historian Herbert Matthews. Matthews’ mystification was later taken up by many well-known historians and journalists, such as Hugh Thomas (1960), Vilanova (1963), Southworth (1963), Cabanellas (1973), Nourry (1976), or more recently Preston (1994) and Herreros (1995). In 1997, in their book El Alcázar de Toledo. Final de una polémica (Madrid, Actas), the historians Alfonso Bullón de Mendoza and Luis Eugenio Togores, gathered sufficient evidence to silence the controversies.]

But let’s come to the crux of the controversy: the figures of repression. Since the end of the conflict, the protagonists and their descendants have never stopped throwing bodies at each other. The figures on repression in both camps have not stopped oscillating over time in an inconsiderate and absurd manner. Authors in favor of the Popular Front have quoted 500,000 dead, 250,000, 192,548 (according to the alleged words of a Franco official who was never identified), 140,000, 100,000 (according to Tamames, then a communist), or “several tens of thousands” (according to Hugh Thomas). For the purposes of his case, Judge Baltasar Garzón used the figure of 114,266 disappeared Republicans. After him, other authors have raised this figure to about one hundred and thirty thousand, ninety thousand of them during the Civil War and forty thousand in the post-war period. These historians also maintain, as their predecessors did, that in the National Zone the repressive action was premeditated and took on the appearance of extermination, even though the Francoists were only victims of repression because the government of the Republic was overwhelmed by uncontrolled groups. The Francoists, on the other hand, relied on the investigations of the Public Prosecutor’s Office in the Causa General (a trial against the “Red Dominion” in the early 1940s, the documentation of which has never been published in its entirety and has been kept in the Archivo Histórico Nacional de España in Madrid since 1980). According to them, it was proven that the Popular Front committed 86,000 murders and the nationals between 35,000 and 40,000.

The most serious assessment of the repression on both sides, which was practically definitive, was that about 55,000 people were killed by the “nationals” and 50,000 by the “republicans.” This relative balance was only broken by the 14,000 judicial executions after the end of hostilities (nearly 30,000 death sentences were handed down by the Councils of War, but half were commuted to prison sentences when the condemned had not committed blood crimes). If one adds to this figure the number of victims of settling of scores during the three months following the end of the fighting, the total number of Popular Front victims of the national camp amounts to 70,000. [See the work of Miguel Platon. For his part, historian Carlos Fernández Santos recorded 22,641 judicial executions (political and common law) between 1939 and 1950.]

Out of a population of 25 million, about 2 million people took part in the conflict in the Popular Front camp. 10% were arrested by Franco’s authorities and about 20,000 were executed with or without trial. This sad and unbearable human toll, especially if one adds to it some 200,000 combat deaths on both sides, does not need to be exaggerated to reflect the magnitude of the disaster. But the allegedly planned extermination amounts to 1% of the opponents and is in no way comparable with the scale of the crimes attributable to the Nazi, Soviet or Maoist regimes.

There are still the continuous polemics about the victims buried in the graves of Francoism. According to socialist and extreme left-wing authors, they contain 110,000, 130,000, 150,000 or even 200,000 unidentified victims spread over 2,000 or even 2,600 graves. According to government sources, over the last 20 years more than 800 graves have been located and opened and nearly 10,000 mortal remains have been exhumed. Since the most important graves have probably been analyzed, extrapolating the figures, the total number of victims cannot exceed 25,000 to 30,000. But it is not known whether the mortal remains of the exhumed disappeared belonged only to civilian victims murdered by Franco’s regime or whether they were also those of republican fighters or nationals, or civilian victims of the Popular Front repression, or Popular Front activists who were victims of the small civil war between anarchists, socialists and communists. Obviously, the reality of the facts is much less important than the effect of the media propaganda.

One example suffices to illustrate the extent of the dangerous passions unleashed by the media on public opinion. At the end of the summer of 2003, an event caused a stir: the discovery of an ossuary in a ravine in Órgiva (Granada), during construction work for the Ministry of Public Works. There was immediate talk of a huge mass grave and of an “extermination for ideological reasons.” The daily newspaper El País even devoted a page to the event, informing that: “According to the data of the socialists, more than 500,000 people were imprisoned and 150,000 others were killed. A professor from the University of Granada described the ravine as a ‘place of crime and death’ where ‘a river of blood flowed.’” Alleged witnesses described the arrival, for days on end, of trucks loaded with “men, women and children,” who were brutally shot down, rolled into the ditch and thrown into the quicklime. This professor estimated the number of victims at 5,000, although the Association for Remembrance, a little less bloodthirsty, reduced the figure by half. The city council decided to erect a monument to the victims in the middle of a park that would be created for this purpose. But after years of unsuccessful excavations, the major newspapers informed their readers on the inside page that according to forensic experts it was a matter of “skeletal remains of animal origin”—to be more precise of goats and dogs.

Other more or less serious polemics, fueled by the works and theses of “official” historians sympathetic to the Popular Front, periodically erupt in the press. Among them, we can mention the “lost or stolen children of Francoism.” It is not a question of the 20,000 or 30,000 “Republican” children sent by their parents to the USSR or France to keep them safe from the conflict, but of the 30,000 children who, during the Civil War and in the post-war period, were “stolen” from their families (and not “adopted”) in the absence of their dead or imprisoned mothers. It is said that the Catholic hierarchy even planned forced disappearances and organized trafficking of minors until 1984 and even into the 1990s. That there were cases of illegally adopted children in Franco’s Spain, as there were in the rest of the world, is beyond doubt—but that the theft was planned on a large scale is doubtful, to say the least. Strangely enough, priests and nuns were also accused of distributing poisoned sweets to workers’ children in 1934.

But the unforeseeable was to happen in the 2000s. In the name of freedom of expression and freedom of debate and research, a large group of historians, some independent, such as Pío Moa, others academics and scholars, such as the American Stanley Payne, and a host of history and political science professors from the Universities of Madrid, Complutense, Rey Juan Carlos, CEU San Pablo, and the Autonomous Regions, protested against the Socialo-Marxist left’s claim to cultural monopoly. [In addition to Pío Moa, these include: Ricardo de la Cierva, Jesús and Ramón Salas Larrazábal, José Manuel Martínez Bande, Vicente Palacio Atard, Carlos Seco Serrano, José María Gárate Córdoba, Enrique Barco Teruel, Luis Suárez, José María García Escudero, José Manuel Cuenca Toribio, José María Marco, Manuel Álvarez Tardío, José Manuel Martínez, José María Gárate Córdoba, César Vidal, Javier Esparza, Ángel David Martín Rubio, Alfonso Bullón de Mendoza, Luis Eugenio Togores, Rafael Ibañez Hernández, Manuel Aguilera Povedano, Antonio Manuel Barragán Lancharro, Alvaro de Diego, Moisés Domínguez Núñez, Sergio Fernández Riquelme, José Lendoiro Salvador, Antonio Moral Roncal, Julius Ruiz, José Luis Orella, Fernando Paz Cristóbal, Pedro Carlos González Cuevas, Francisco Torres, Javier Paredes, Miguel Platon, Carlos FernándezSantander or Jesús Romero Samper.]

In 2007, seeing it impossible to silence the many dissenting voices of historians and journalists, the head of the socialist government, José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero and his allies, chose, on the initiative of the communists of Izquierda Unida, to resort to a “memory” law. This “law of historical memory,” passed on December 26, 2007, is intended and justified as a “defense of democracy” against a possible return of Francoism and “ideologies of hatred.” In reality, it is a discriminatory and sectarian law that is in no way democratic. It legitimately recognizes and amplifies the rights of those who suffered persecution or violence during the Civil War and the dictatorship (laws of 1977, 1980, 1982 and 1984 have already been enacted to this effect). But, at the same time, it gives credence to a Manichean vision of history that contravenes the most elementary ethics.

The fundamental idea of this law is that Spanish democracy is the legacy of the Second Republic (1931-1936). But beyond that, it makes the Second Republic, the Popular Front and the revolutionary process (1934-1939) the founding myth of Spanish democracy, an idyllic period in which all the parties of the left were blameless. The right-wing is then solely responsible for the destruction of democracy and the Civil War. To top it all off, to question this historical lie is an express or disguised apology for fascism.

This law led to the exaltation of victims and murderers, of the innocent and the guilty when they are in the camp of the Popular Front and only because they are of the left. It confuses the dead in action of war and the victims of repression. It casts a veil of oblivion over the “republican” victims who died at the hands of their left-wing brothers. It encourages any work aimed at demonstrating that Franco deliberately and systematically carried out bloody repression during and after the Civil War. Finally, this recognizes the legitimate desire of many people to be able to locate the body of their ancestor, but implicitly denies this right to those who were in the national camp under the pretext that they would have had time to do so during the Franco era.

Theoretically, the purpose of this law is to honor the memory of all those who were victims of injustice for political or ideological reasons during and after the Civil War. But it refuses to recognize that during the Republic and the Civil War many crimes were committed in the name of socialism-Marxism, communism and anarchism, and that these monstrosities can also be qualified as crimes against humanity (for example, the massacres of Paracuellos del Jarama and of the “Chekas,” and the massacres during the persecution of Christians).

[The graves of Paracuellos del Jarama, a few kilometers from Madrid, contain the mortal remains of approximately 2,500 to 5,000 victims of the Popular Front. One of the main perpetrators of this massacre was the communist Santiago Carrillo. These executions, organized in November and December 1936, were stopped thanks to the intervention of the anarchist leader Melchor Rodríguez García. During the Civil War, the “Chekas” (named after the Russian Cheka), were torture centers, organized by the different parties of the Popular Front, in all the big cities. There were more than 200 of them in Madrid and more than 400 throughout the Peninsula (see César Alcalá, Las checas del terror, 2007). Throughout the conflict, the executions, immediate in the national camp, were frequently preceded by terrible tortures in the Republican camp.]

Since its enactment, the “law of historical memory” has been systematically interpreted in favor of representatives and sympathizers of the Republican or Front-Populist camp and their descendants alone. The return to power of the right wing, three years after the onset of the economic and financial crisis of 2008, was not likely to change this. The leader of the Popular Party, Mariano Rajoy, president of the government from 2011 to 2018, did not dare to repeal or modify the law.

With the adoption of this law, the Pandora’s box is open. History becomes a suspect subject. It is replaced by “historical memory,” which is based on individual and subjective memories, which are not concerned with explaining and understanding, but with selecting, condemning and denouncing. Elected to the presidency, in June 2018, the socialist Pedro Sánchez, soon demonstrated this. To stay in power, Sánchez, who represents the radical tendency of the PSOE, has allied himself with the far left (Podemos and PC/IU) and the nationalist-independents, even though he had sworn never to do so before the elections. He appeases Brussels and Washington on the economic and financial fronts, and at the same time gives cultural and societal pledges to his most radical political associates.

As early as February 15, 2019, Sánchez’s first government pledged to proceed as quickly as possible with the exhumation of the remains of the dictator Francisco Franco, buried forty-three years earlier in the choir of the Valle de los Caídos basilica. On September 15, 2020, less than a year after carrying out the transfer of the ashes, he decided to pass, as soon as possible, a new “Draft Law of Democratic Memory,” which would repeal and strengthen the “Law of Historical Memory” of 2007. In the name of “historical justice,” the fight against “hatred,” against “Francoism” and “fascism,” a disguised way of cancelling or diverting the amnesty law, Sánchez’s socialist-Marxist coalition wants to promote moral reparation for the victims of Francoism and “guarantee the knowledge of democratic history to citizens.”

This draft law provides, among other things, for the allocation of public funds for the exhumation of the victims of Francoism buried in mass graves; the prohibition of all “institutions that incite hatred;” the annulment of the judgments handed down by Franco’s courts; the updating of school curricula to take into account true democratic memory; the expulsion of the Benedictine monks who guard the Valle de los Caidos; the exhumation and removal of the mortal remains of José Antonio Primo de Rivera; the desecration or “redesignation” of the Basilica of the Valle de los Caídos, which will be converted into a civilian cemetery and a museum of the Civil War; and fines of up to 150,000 euros to punish all violations of this law.

[Founder and leader of the Falange, the young Madrid lawyer, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, was imprisoned four months before the military uprising. Illegally detained between March 14, 1936 and July 18, 1936, he was nevertheless sentenced to death for participation in the uprising and shot under pressure from the communists, with the tacit agreement of Largo Caballero’s government, on November 20, 1936 (See Arnaud Imatz, José Antonio: entre odio y amor. Su historia como fue, 2006 and José Antonio, la Phalange Espagnole et le national-syndicalisme, 2000).]

The reality of this draft law, which claims to defend peace, pluralism, human rights and constitutional freedoms, is tragic. It is not the prohibition of the cult of Franco that divides Spain, but the definition or meaning that this new bill intends to give to “apology for Francoism.” It renews and reinforces the use of the Civil War as a political weapon. It discriminates against and stigmatizes half of the Spanish population; erases the existence of the victims of Popular Front repression; refuses to annul even the symbolic sentences handed down by the People’s Courts of the Republic; and blithely ignores the responsibility of the revolutionary left for some of the most horrific atrocities committed during the Civil War. Only the “progressive” view of the past, as defined by the current socialist-Marxist authorities, is considered democratic; the history of the “others” is to be erased, as was the case with the history manipulated in the Soviet Union. The Spanish authorities seem to seek peace only through division, agitation, provocation, resentment and hatred. Justice takes the form of resentment and revenge. Spain is slowly but inexorably sinking into a global crisis of alarming proportions.

With this grim political background in mind, let us return to Pío Moa’s present book. In 2005, a Parisian history publisher acquired the French rights to Los mitos de la Guerra Civil. A renowned translator was immediately commissioned. Specialist in Marxism and totalitarianism, the latter had been a Maoist and a member of the steering committee of Sartre’s review Les Temps modernes in his youth. A year later, in 2006, the year of the 70th anniversary of the Spanish Civil War, the book (as well as its ISBN number) was publicly announced. But without explanation the date of publication was postponed several times and then publication was canceled. A collective work was finally published: La guerre d’Espagne: l’histoire, les lendemains, la mémoire (2007): Actes du colloque Passé et actualité de la guerre d’Espagne, 17-18 novembre 2006, a book edited by Roger Bourderon (specialist on the PCF, former editor of the Marxist-inspired review, Les Cahiers d’histoire). This was preceded by the opening speech of the socialist activist, Anne Hidalgo, then deputy mayor of Paris.

After so long being a mere “Arlesian,” thanks to the open-mindedness, independence and intellectual courage of the management of Éditions de l’Artilleur /Toucan, the updated and completed version of Pío Moa’s book, Les mythes de la guerre d’Espagne, is finally available to the French-speaking reader, who can now inform himself and judge for himself, freely and above all with full knowledge of the facts.

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés.

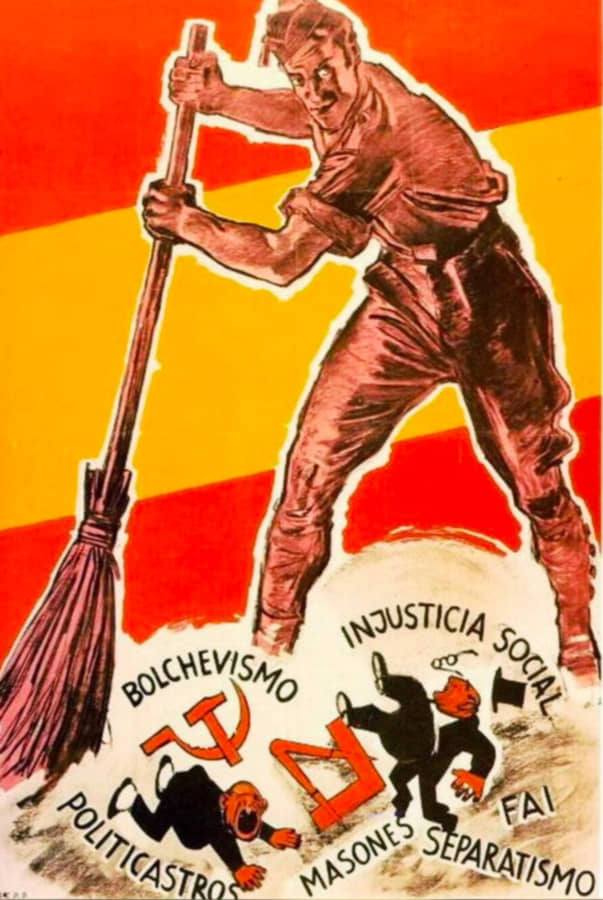

Featured image: National poster, ca. 1938, showing a soldier sweeping away Bolshevism, corrupt politicians, social injustice, masons, separatists, and FAI (Anarchist Federation of Iberia).