Among critical minerals, some occupy a special place. For example, it is difficult to imagine the normal functioning of a large metropolitan city without salt. In the Middle Ages, many countries experienced so-called salt riots due to salt shortages or tax increases. The situation is similar with petroleum products, on which the transportation system of any state is heavily dependent. Some rare-earth or other metals are not so prominent in the list of critical resources, but they are necessary for the production and uninterrupted operation of a country’s infrastructure system.

For example, we use lithium-ion batteries in our daily lives. From ordinary “finger” batteries, cell phones, laptops and home appliances to electric vehicles, drones and specialty equipment like submarines—and all of these devices require lithium. Lithium and its derivatives have other industrial uses as well. Lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) is used in the production of glass and ceramics, as well as in pharmaceuticals. Lithium chloride (LiCl) is used in the air conditioning industry, while lithium hydroxide (LiOH) is now the preferred cathode material for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles.

Lithium is valuable as a recharging material because it stores more energy in proportion to its weight than other battery materials.

It is a toxic metal that is difficult to mine (100 tons of ore must be processed to produce one ton of lithium) and to dispose of, but nevertheless, its reserves are being hunted around the world.

Globally, lithium is considered to be a strategic but not scarce resource. It occurs in nature in a wide range of forms, mostly in low concentrations. Today, it is economically feasible to extract lithium from two sources—brines (continental and geothermal), or “hard rock” (pegmatites, hectorite and jadarite). Brines account for approximately 50% of the world’s reserves (source).

Manufacturers use more than 160,000 tons of this material annually. Global lithium consumption is expected to be at least 200,000 tons by 2025, and is expected to grow nearly 10-fold further over the next decade.

But there is a geographical nuance—its deposits are limited to a small number of countries, so the issues of its extraction automatically acquire geopolitical significance.

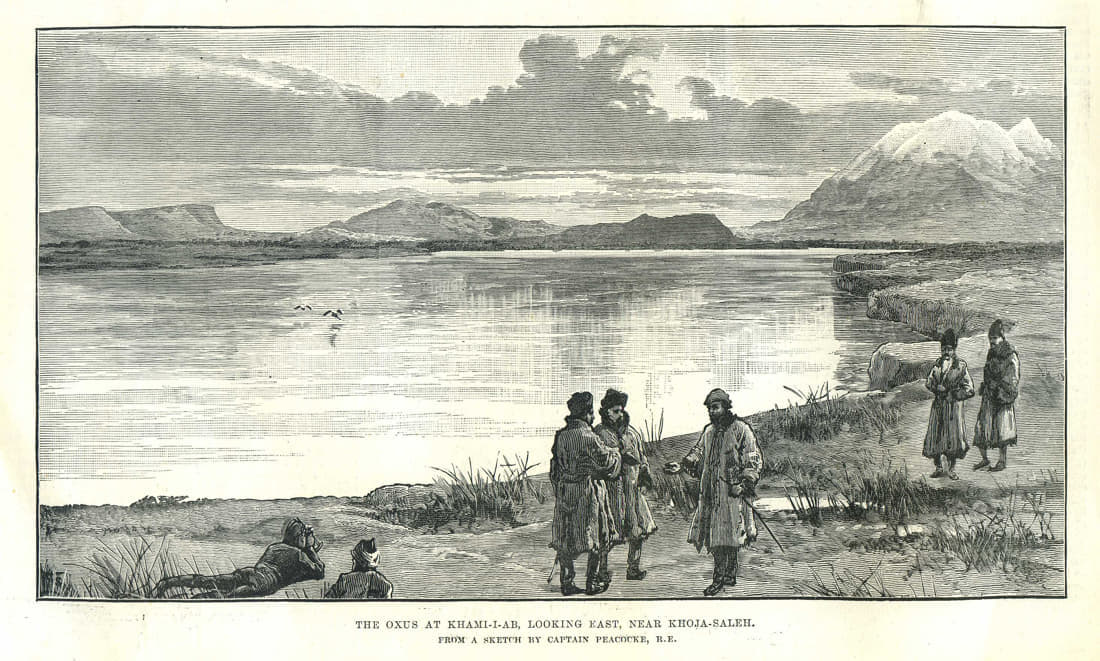

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the largest lithium resources in the world as of last year were located in Bolivia, where they were estimated at 21 million tons, Argentina (19 million tons), Chile (9.8 million tons), the United States (9.1 million tons), Australia (7.3 million tons), and China (5.1 million tons). The Service estimates Russia’s projected lithium reserves at 1 million tons (source).

Bolivia, Argentina and Chile represent the so-called lithium triangle. It is considered to be of increasing strategic importance as countries seek to gain a technological advantage by controlling the lithium industry. This triangle uses the vaporization method, so the cost of lithium there is lower than in mining. It is estimated that the lithium triangle in the salt marshes of Bolivia, Chile and Argentina accounted for 56% of global resources, 52% of global reserves and one-third of global production in 2021.

In Chile, lithium is considered a strategic resource. Decree No. 2886 (Ministerio de Minería, 1979) declared it reserved for the state and excluded it from all mining concession regimes, except for those entities that held mining concessions (pertenecias mineras) prior to 1979. As a result, two private companies have been mining lithium for more than 25 years—the U.S. company Albemarle and Chemical & Mining Co. of Chile Inc, both operating in concession areas of the Chilean Corporation for the Development of Production (CORFO) in the Atacama Salt Plain.

In Argentina, the situation is somewhat different. US companies have been mining lithium there for more than 20 years, and now Canadian, Australian, Chinese and Japanese companies have joined them. Over the past decade, Argentina has been the most dynamic country in terms of lithium production expansion, with some 38 projects in various stages of preliminary implementation. Nevertheless, the national government does not consider lithium a strategic resource (with the exception of the province of Jujuy, which has declared it strategic). As with any other mining activity, the regulatory framework is based on the National Constitution, the Mining Code and the Mining Law. The management of mining resources is delegated to the provinces. The federal framework grants the provinces the rights to determine concessions to private and public entities and the norms for regulating mining activities within their jurisdiction.

To date, there are two main production sites in Argentina:

• a public-private partnership in Salar de Olaroz (Jujuy Province) operated by Sales de Jujuy S.A., owned by Orocobre Limited, in a joint venture with Toyota Tsusho Corporation (TTC) and Jujuy Energía y Minería Sociedad del Estado (JEMSE—a company owned by the Jujuy Provincial Government);

• a private company (Minera del Altiplano S.A.), owned by Livent (formerly FMC Corporation) operating in Salar del Hombre Muerto (Catamarca province).

Bolivia is a special case; although it has the world’s largest lithium deposit, it has not entered the global lithium market in any meaningful way. The governance structure defines lithium’s strategic status and centralized state management through the state-owned mining company, Yacimientos del Litio Boliviano (YLB). For over a decade, with a public investment of approximately US $1 billion, the government strategy has focused on building infrastructure for the LIB value chain, but has had extremely modest results in terms of lithium carbonate production.

Only during the industrialization phase of cathode and battery production is space created for public-private partnerships, with the government retaining at least 55% of net profits. In December 2018, YLB formally registered a joint venture (YLB-ACISA) with Germany’s ACI Systems GmbH for a lithium hydroxide industrial complex, but the Evo Morales government canceled the contract amid protests in Potosí against the terms of the agreement. Earlier that year, the Morales government also signed a joint venture agreement with Chinese consortium Xinjiang TBEA Group-Baocheng to explore and extract resources in the Coipas and Pastos Grandes salt marshes.

Recently, Bolivian state-owned YLB and China’s CATL BRUNP & CMOC (CBC) signed an agreement under which the Bolivian side will oversee the entire soft metal industrialization process, from mining to commercialization. The Chinese partners will invest more than $1 billion in the costs of commissioning and construction of industrial complexes.

The agreement includes the creation of two industrial complexes with direct lithium extraction technology in Potosí and Oruro.

Brazilian professor Bruno Lima believes that “if other countries copy Bolivia’s model of industrializing lithium production and enter into profitable partnerships for technology transfer, they will succeed.”

In his opinion, “[Bolivia] will not limit itself to selling to the international market, but will create a complete cycle. Part of the lithium is sold to the international market, such as China, but the other part goes to processing, transfer and technological development.”

He adds, however, that “if these operations were conducted outside the dollar standard, that would be ideal. We are really talking about a qualitative leap for Latin American presence in the market and in the international system” (source).

It should be noted that Bolivia deliberately keeps US companies out of Bolivia, understanding their intentions and goals. In 2022, the US company EnergyX was disqualified there. The aforementioned German ACI has also run into problems.

Since in the case of ACI, the key decision involved recognizing the rights of local communities to benefits and compensation in their territories, as well as the risk of environmental damage, these interrelated trends will only intensify.

However, environmental aspects are directly related to lithium extraction in one way or another, regardless of who is involved. While there is a wide range of lithium extraction methods available, the main ones, including hard rock mining and the extraction of lithium from seawater, require large amounts of energy. These processes disrupt natural groundwater levels, local biodiversity and the ecosystems of nearby communities. For example, nickel mining and refining practices have already resulted in documented damage to freshwater and marine ecosystems in Australia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and New Caledonia.

Pollution from this work not only impacts oceans and ecosystems, but also creates environmental hazards throughout the life cycle of batteries, from the extraction of raw materials for their production to the disposal of old batteries in landfills, creating health risks for workers and impacting nearby communities due to the toxicity of heavy metals such as lithium (source).

Therefore, environmental requirements will become stricter and new extraction and recycling technologies will be welcomed.

It would seem that seawater could solve the problems of supplying lithium to markets, because the world’s oceans contain 180 billion tons of lithium. But its percentage lithium content is about 0.2 parts per million. Existing evaporation technologies are time-consuming and require special areas, so they are not economically feasible.

A new approach is to create special electrodes that act more selectively. Such experiments are being conducted at Stanford University, where the electrode is coated with a thin layer of titanium dioxide as a barrier. Since lithium ions are smaller than sodium ions, it is easier for them to squeeze through the multilayer electrode. In addition, the way in which the electrical voltage is controlled has been changed to improve efficiency, although this method is still quite expensive (source).

In terms of corporate structure, the world’s lithium suppliers are five major companies—Albemarle (USA), Ganfeng (China), SQM (Chile), Tianqi (China) and Livent Corp (USA) (source).

Battery production has a slightly different geography. In 2021, Australia, Chile, and China accounted for 94% of global lithium-ion battery production. But in recent years, Chile has lost its leading role in the global lithium market as Australia has rapidly expanded its hard rock mining operations.

It should be noted that lithium is fully recyclable, so it is not a consumable commodity like oil. Accordingly, even if lithium batteries do begin to significantly displace internal combustion engines, we will not necessarily see a “lithium policy” replace today’s “oil policy.” Nevertheless, if demand for electric vehicles increases dramatically in the coming years (projected to reach $985 billion by 2027), countries with large lithium reserves will wield far more power than they have in today’s economic and geopolitical hierarchy (source).

Because of this, the U.S. fears that “because lithium supply chains will be critical to the future of technology and clean energy, lithium will play an important role in the competition between the United States and its rivals, mainly China, in the coming years. China currently leads the world in electric vehicle production. This is largely due to the fact that it has acquired 55% of the chemical lithium reserves needed for electric car batteries, mainly through its early investments in major mining operations in Australia.” (source).

The EU is also concerned about its dependence on lithium supplies. In the upstream segment of the value chain, Chile provides more than 70% of the EU’s lithium supply. Since other minerals are also needed to make batteries, the dependence extends to other countries in the big picture.

The Democratic Republic of Congo supplies more than 60% of the cobalt processed in the EU. China, for its part, meets about half of the Union’s total demand for natural graphite. Moreover, the EU’s international dependence in the low-carbon sector also stems from the fact that its own battery cell production capacity is still relatively weak. In 2020, EU battery production accounted for just 9% of global battery production (source).

It is only natural that the EU is trying to prioritize high-risk investments in battery designs that are less dependent on scarce natural resources such as cobalt, nickel or lithium.

Geopolitical tensions and possible lithium supply disruptions are not only being highlighted in the West.

In May 2023, Asia Times noted that the top three producing countries process more than 80% of the most important minerals used in lithium batteries. China dominates the processing of almost all minerals, holding more than 50% of the total market share, with the exception of nickel and copper, of which China controls 35% and 40% respectively.

Technology-intensive industries rely on interdependencies between countries with different endowments. This works well during periods of geopolitical stability and cooperation but the high concentration of processing in the lithium battery supply chain means that it is vulnerable to disruption by war, global pandemics, natural disasters or geopolitical tensions.

Australia has the world’s largest battery-grade lithium deposits, and export revenues have skyrocketed, with lithium becoming Australia’s sixth most valuable commodity export. Australia needs to consider how to profit from the boom and what role it can play in the lithium race.

Australia and China complement each other in this supply chain. Australia supplies 46% of lithium chemicals and a large proportion goes to Chinese processing facilities and then to Chinese battery and EV makers.

China produces 60% of the world’s lithium products and 75% of all lithium-ion batteries, primarily powering its rapidly growing EV market, which accounts for 60% of the world’s total.

Australia moving up the value chain would require investment and technology, and bear a significant environmental cost. Without scale advantages, Australian-made products will fail to achieve global competitiveness. Australia must consider long-term industrial policies that enable the country to play a role in fighting against climate change rather than being caught between the superpower competition.

Australia is entangled in the superpower competition between China and the United States over the control of lithium.” (source).

And the US still lags behind China in lithium mining and battery production. An estimated 3.6% of the world’s lithium reserves are concentrated there, with a single lithium mine in Nevada (although others are planned), and only 2.1% of the world’s lithium is processed.

But in the 1990s, the U.S. was the leader in lithium production. The industry was undermined by a combination of cheaper production overseas, strict environmental regulations and the empowerment of indigenous peoples, who often own property where there are lithium mines. The big push for clean technology has changed U.S. priorities—unless the United States develops domestic sources of lithium or secures additional sources abroad, it faces a threat to its national security as China expands its own access to the resource (source).

The current situation also raises the issue of control over lithium supplies, as the West is trying to impose all sorts of sanctions on unwanted states that pursue independent policies. And, according to the author of the RAND Corporation, it is not so easy to do this. “The special requirements for suppliers of critical minerals to receive credit for clean vehicles are designed to encourage increased production outside of China, which dominates global supply chains for electric vehicle batteries. A certain percentage of the minerals must be domestic or from a country with which the United States has a free trade agreement, and none can come from a “foreign interested party,” which includes China. The dominance of any one source of supply leaves the rest of the world vulnerable to disruption, and the fact that that source is China only heightens the fears of the United States and its allies” (source).

Another RAND publication noted that China has a huge share of lithium-ion battery production. Today, it produces 91% and 78% of all battery anodes and cathodes, respectively, and 70% of the world’s battery production. China has also demonstrated that it is willing to restrict exports of critical minerals, such as rare earth elements, to coerce trading partners. Such export restrictions could negatively impact the entire U.S. economy and, in particular, the growing market for electric vehicles. But they could also undermine the defense industry’s ability to support the U.S. military (source).

After all, there are certain indicators by which technological superiority in geopolitical competition can be determined. And in our case, gigafactories are a key indicator of who and where will dominate electric vehicle platform technology (and beyond). The term, originally coined by Tesla, refers to large-scale electric battery manufacturing capacity (for electric vehicles and energy storage). Capacity is measured in gigawatt hours (GWh). The relevance of these gigafactories has increased dramatically over time as this resource has become a major source of foreign direct investment and has become necessary to support battery-related industries, vehicle manufacturers, and supply chains. According to the Automotive database (2021), Europe has only 25% of gigafactories, while Asia has 71% (China owns 69% of capacity). As China leads in gigafactory capacity at the speed and scale required by global demand, gigafactories could become a “geopolitical hotspot” beyond purely geographic concentration of infrastructure (source).

At the same time, China’s expansion into other markets is noticeable. For example, China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Limited (CATL) not only had 22% of the total global gigafactory capacity of 500 GWh in 2021, but is now expanding its operations in Europe and is likely to increase its presence in the United States and other key regions.

In 2022, there are 92 gigafactories in Asia, 23 in Europe, and 13 in North America. So the percentages are as follows – 72, 18 and 10. Paradoxically, Latin America, which accounts for the bulk of lithium production, has no gigafactories at all. Neither does Africa.

As for Russia, the lithium boom is just beginning. During SPIEF-2023, an agreement was signed on the development of the Kolmozersky lithium deposit in the Murmansk region. The development of the deposit will make it possible to create Russia’s first production of lithium-containing raw materials, which will make it possible to supply advanced Russian enterprises with lithium. Among them is a factory for the production of lithium-ion batteries in the Kaliningrad Region, which is scheduled to be launched in 2025. The deposit itself contains about 19% of Russia’s lithium reserves. Its ore also contains valuable strategic materials—beryllium, niobium and tantalum (source).

We can only hope that the experience of other countries will be taken into account and Russia will have at least a little more domestic gigafactories.

Leonid Savin is Editor-in-Chief of the Geopolitika.ru Analytical Center, General Director of the Cultural and Territorial Spaces Monitoring and Forecasting Foundation and Head of the International Eurasia Movement Administration. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Geopolitika.