A quarter of a century ago, on March 24, 1999, a combined group of NATO countries launched a military campaign against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which at that time consisted of Serbia and Montenegro.

Over the years, quite a lot has been written about the consequences of this aggression—about the clear violation of the principles of international law, since the UN did not sanction any military action against a sovereign state; about the numerous human rights violations during the bombing; about the commissioned information campaigns against the Serbs, which had nothing to do with reality; and about the impact of the war on the civilian population—from post-traumatic stress syndrome to the increase in cancer because of the use of munitions with depleted uranium cores.

However, several important points should be emphasized. This campaign was NATO’s first offensive operation. The military-political bloc, which was conceived ostensibly for defense against a possible attack from the Soviet Union (a figment of the crazy imagination of Western, primarily Anglo-American, politicians) became an instrument of military expansion. From conditionally defensive, it became offensive. First in Europe and then in other parts of the world, in particular against Libya in 2011. The military campaign against Yugoslavia probably gave NATO strategists confidence in the need for further expansion and homogenization of the whole of Europe under the umbrella of Brussels. The next expansion of the alliance came in a whole bundle. In March 2004, seven states were admitted at once: Bulgaria, Romania, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Slovenia. There is one interesting nuance here—all these countries signed the membership action plan in April 1999, that is, when the bombing of Serbia was in full swing. The connection between the aggression and the co-option of new members is obvious. It should be noted that actually on the eve of the aggression against Yugoslavia on March 12, 1999, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, which received an invitation to join in July 1997, joined the alliance. Now NATO’s tentacles are creeping into the Caucasus, the Middle East and Central Asia, as the alliance has various agreements with a number of states in the regions mentioned.

Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic’s signing of an agreement to withdraw from the province of Kosovo and Metohija and hand it over to international forces did not mean total political defeat. He remained in power. Although already in May 1999, the Hague Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia brought charges against Milosevic for war crimes in Kosovo. To get him, it was necessary to lift the diplomatic immunity enjoyed by heads of state.

External tools such as sanctions helped to put pressure and increase social tensions. Agencies at the same time worked on the ground and pumped money into the opposition. The puppet movement Otpor, acting as if on behalf of Serbian citizens, adopted Gene Sharp’s methodology of non-violent (conditionally) resistance and continued to implement its plan step by step.

The moment of the election campaign was chosen to bring people out on the streets.

In October 2000, because of mass protests, Slobodan Milosevic resigned, without waiting for the second round of presidential elections. In fact, the first color revolution, called the “bulldozer revolution,” was successfully implemented in Serbia. What is striking is that many of its thought leaders, such as Professor Cedomir Čupić, are still living quietly in Belgrade and actively criticizing the current authorities. While the younger ones, such as Srdja Popovic, immediately defected to the West and continue their attempts to stage coups d’état in other countries.

Let us now look at the global context of NATO’s war against Yugoslavia.

It should be taken into account that earlier in Yugoslavia a civil war was raging, and NATO countries, including the United States, were actively involved in Bosnia. This gave them an opportunity not only to practice ethnic conflict technologies, as well as new theories of warfare, such as network-centric warfare, but also to use both private military companies and mercenaries (in particular, mujahideen who had previously fought in Afghanistan were brought in as part of the “jihad”). This whole machine was directed against the Serbs, not only to gain operational superiority on the front, but also with far-reaching strategic objectives, which included demonization of the Serbs, creating the image of barbarians who pose a threat to the “civilized world.” And this demonization was successful and was already consolidated in 1999. But if the West then openly blamed the Serbs, it also meant the Russians, who tried to help their brotherly people to withstand the pressure of the West. It is no coincidence that Slobodan Milosevic warned that what the West had done to the Serbs, it would try to do to Russia in the future.

However, a scenario similar to the Yugoslav one had already been conceived for Russia. In the spring of 1999, terrorist organizations intensified their activities in Russia’s North Caucasus. In April, when NATO was bombing Yugoslavia, the self-proclaimed “emir of the Dagestan Jamaat” announced the creation of an “Islamic army of the Caucasus” to carry out jihad in southern Russia. Then began a whole wave of terrorist attacks organized by terrorists under the leadership of Shamil Basayev—seizure of settlements in Dagestan, bombings of houses in Moscow and Volgodonsk.

Therefore, when the question is raised whether Russia could have helped the Serbs more than it did, including the operation to block the Pristina airport, we must remember that the situation was quite difficult for us as well. The North Caucasus was in flames, emissaries of Western security services were working in the Volga region, and separatist projects were emerging in the regions.

It was an active phase of the unipolar moment, which the U.S. used to strengthen its hegemony all over the world, not shying away from any means, including terrorism. And its decline was still far away.

But were there positive outcomes of NATO’s military aggression against Yugoslavia? Let us try to summarize. First: the Yugoslav army seriously repulsed the enemy and as a result NATO had significant losses, which they did not expect initially. Various military tricks were used in different types of military forces and which may well now be adapted for the Special Military Operation (SMO), with appropriate adjustments. Second: the real face of NATO was seen by the whole world, which led to anti-war protests. In particular, Italy left the coalition because of this. Third, the dirty methods of information campaigns and the use of non-governmental organizations as a fifth column were documented and widely publicized. Finally, the international solidarity with the Serbs—Russian volunteers and humanitarian aid, the work of hackers from different countries against NATO, the circumvention of Western sanctions—is also an important experience of a complex nature, which will be useful for crushing the globalist military hydra of the North Atlantic Alliance.

Leonid Savin is Editor-in-Chief of the Geopolitika.ru Analytical Center, General Director of the Cultural and Territorial Spaces Monitoring and Forecasting Foundation and Head of the International Eurasia Movement Administration. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Geopolitika.

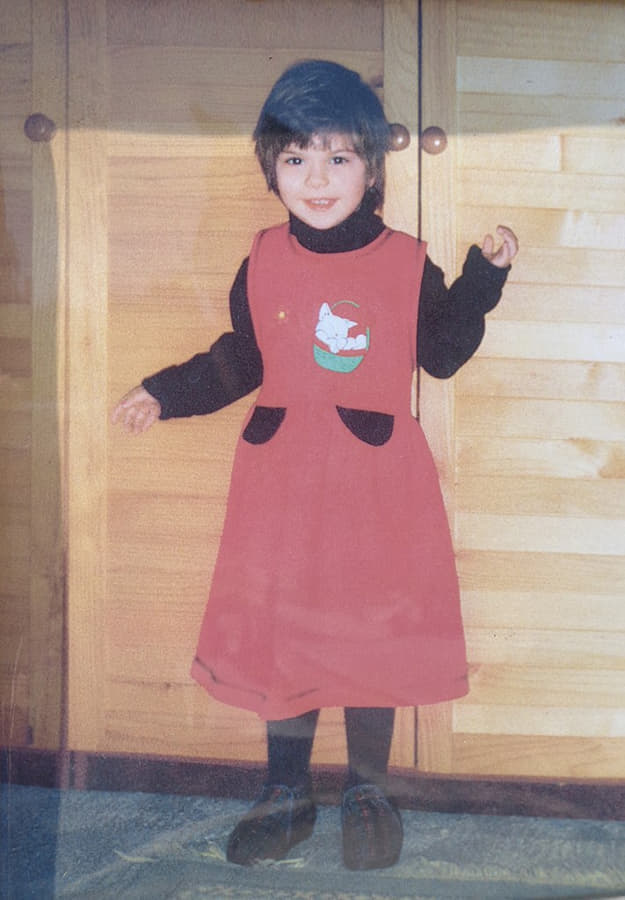

Featured: Milica Rakić, 3-years-old, killed on April 17, 1999, by a cluster munition during the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.