Read Part 1 and Part 2.

The Modern Metaphysical Roots of the New Technocratic World

Introduction

In the first two parts of this essay, I focused upon the globalist purpose behind the destructive domestic use of disinformation within the US-European imperial axis which has asphyxiated liberal democracy, and some of the major geopolitical machinations that have proceeded on the back of fake news. This third part of the essay addresses a larger philosophical set of concerns that might superficially be seen as of little relevance to the crisis of the West today as it sits amidst civil wars and a world war.

This third part is a reflection upon the destructive drives within modern metaphysics beginning with its reconstitution of the cosmos as one in which faith in God is replaced by faith in the powers of our own mind. That faith has come to reveal behaviors as monstrous as any summoned by the human spirit—from the death camps of the all-knowing leaders (Dostoevsky’s God-men), Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Pol-Pot etc. to the deluded sense of sanctimony of a people caught up in the abstractions of rights’ talk that has fueled the West’s support of a war against Russia in the name of Ukraine liberation to the battle ground now taking place over children as fully sexualized beings to be inducted into the larger culture of the West’s self-understanding as a rights’ and dignity based pleasure sensorium of sexualized identities. This seemingly recent outbreak of the war over childhood sexualism has a long pedigree. Decisions made about US school curricula in sexual education and explicit sex materials being placed in schools go back well over a decade, but the sexual revolution of the 1960s was also accompanied by various calls to lower the age of sexual consent and to overturn prosecutions of adults for sexual conduct with minors.

While it would be hard to argue against the idea that the smashing of sexual restrictions was not an important part of the call to “emancipate” children’s sexuality, one should not also neglect the fact that what was also being overthrown was the idea of the role of adults requiring taking on responsibilities demanding sacrifices. In traditional societies children become inducted into roles and the roles they take on are seen as essential to the group’s survival and well-being.

What happened in the West was the growth of an idea, going at least back to Rousseau, that children knew and should live in accordance with their own nature, albeit with the guidance of tutors such as Émile’s tutor who somehow are able to absolve themselves through their own thinking from the determinations which the rest of the civilized suffer from. As with so much else in Rousseau, the acceptance of this new idea required a break with all preceding social mores—and Rousseau always trusted his intelligence more than the collective intelligence of human beings that preceded him, because they were simply products of human nature deformed by private property, inequality and self-interest.

While Rousseau still had ideas of some sort of transcendence needed for the child’s development, in spite of his determination to liberate the child from prejudice and be more in tune with its innermost nature, he opened up a way of thinking in which the liberation of the self was predicated upon the liberation of the child. And instead of the child being exposed to and required to perform daily acts of the self’s transcendence, instead of experiencing the important lesson that the self becomes a worthwhile self by bowing to higher things of the spirit, and thereby slowly being raised by that spirit, the infant became the center. Freud would christen that infantile center the Id, and whilst doing so, make the sexuality of the infant an important clue to the development of. a person. To be sure he did concede that society could not exist if it merely catered to the sexual drives, and in Civilization and its Discontents, he claimed that it was precisely because the sexual drives were cordoned into more productive enterprises that civilization existed.

At the same time, the core article of faith of Freudian psychology was that the repression of the sex drive from infancy on was the source of most of our psychological distress. How to achieve a balance between our urge to satiate our sexual appetites and how to be civilized required a new kind of priest, mainly Mr. Freud and others who offered the ‘talking cure’ that he had pioneered. It was the kind of thing that appealed to people who like that kind of thing, but it certainly had social efficacy—and to repeat, it placed the desires of the infant at the center of all our psyches and hence at the center of society.

When Herbert Marcuse wrote Eros and Civilization he had hit upon the perfect match—Marx plus Freud—which would supposedly satiate the needs of the modern soul—a social means of production in which as Marx would put it, “from each according to his ability to each according to his needs,” which is to say we could have all the stuff we needed, as well as a grand sex life, provided we got rid of the ruling class and their need to repress our sexual desire so that we could live our lives playfully pursuing our desires. Marcuse was, of course, a huge hit with the youth of the 1960s, and his social “philosophy” is really an adult child’s view of what life has to offer.

The youth he taught were also the beneficiaries of the scientific studies being conducted by the Kinsey Institute and hitting the book stores in 1948 and 1953, respectively, with the Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male and Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female. Kinsey’s “scientific” studies confirmed Freud’s observation infants were sexual beings, and had orgasms.

As Kinsey reported “Orgasm has been observed in boys of every age from 5 months to adolescence. Orgasm is in our record for a female babe of 4 months. After describing in detail the physiological changes that occur during orgasm as well as the aftermath Kinsey discloses that “there are observation of 16 males up to 11 months of age, with such typical orgasm reached in 7 cases. In 5 cases of young preadolescents, observations were continued over periods of months or years, until the individuals were old enough to make it certain that true orgasm was involved.”

Defenders of Kinsey’s studies dismiss the idea that these studies suggest pedophilia must have been happening. Given that Kinsey’s studies were based on “observations” one can only conclude, as Judith Reisman has noted, and as one of Kinsey’s colleagues, C.A. Tripp, in a 1991 interview with Phil Donahue, claimed, that Kinsey’s “trained observers” were pedophiles.

The arc from Kinsey’s reports to sex education courses containing graphic content of children leaning about cunnilingus, anal sex and such like is part of a hyper-sexualized infantile culture, a culture in which adults dress up and play out their fantasies even in the institution of the military. The sexualization of children that proceeds at such a pace today and is lauded by public officials, corporations, teachers, medical professionals, the media and entertainment industries is but one further expression of a culture that has been built upon the expansiveness of the infantile self. The infantile behavior of the adults is best gratified by behaving with children, and as the most meaningful part of the adults’ lives is their pursuit of pleasure, it would be wrong of them not to have children learn what they know—or be what they be. The child has the right to the sexual identity it wants: the rights of the child are the expression of the childishness of the rights being demanded by people who think their suffering in not having their sexual fantasy or not having the pronoun they want is akin to genocide.

This en-culturalization of the infantile self is, though, but the inevitable development of what happens when a society’s faith in technicians who can manipulate bodies as they deem fit for the maximization of one’s own sense of self, and the array of pleasures that await that self if the adequate technological adaptations are made. That self is nothing more than an appetitive bundle of mechanistic processes. All differences between persons are purely of a mechanical order. Thus, too, the difference between an adult and child is only one of the imagination’s prejudices.

Sex with and torture of children was a regular feature in the Marquis de Sade’s stories of gargantuan sexual horror rituals—the children’s role was to be the ultimate stimulant to burst beyond the social limits and curtailment of the imagination. But de Sade understood, as he never ceased to tell his audience, that he was only acting in accordance with reason which was attuned to the mechanical laws of the universe. For much of the twentieth century philosophers and authors have celebrated the transgressions of de Sade, from Sartre and de Beauvoir, to Bataille, to Klossowski, to Blanchot, to Derrida—his admirers are a virtual list of the French intelligentsia. They, though, rarely appreciate what Sade incessantly reminded his readers of, that his philosophy simply expressed the natural conclusion of mechanistic metaphysics.

The post-structuralist philosopher Gilles Deleuze is one of the more self-aware of the modern mechanists. His philosophy draws upon numerous precursors, but his reworking of Spinoza’s pan-immanentism and Leibniz’s dynamic monadism is used to develop a philosophy of excess and surplus generating endless difference. In one of his best known works, Anti-Oedipus, cowritten with Félix Guattari, Deleuze holds that Freud tries to constrain desire so that it tapers into the confines of the family. For Deleuze humans are not a “thou” nor an “I” (for Deleuze anything which spelt of a metaphysical privileging and ascribing any kind of transcendence to human beings was a regressive philosophical step) but just another “it.” And this: “It is at work everywhere, functioning smoothly at times, at other times in fits and starts. It breathes, it heats, it eats. It shits and fucks. What a mistake to have ever said the id. Everywhere it is machines—real ones, not figurative ones: machines driving other machines, machines being driven by other machines, with all the necessary couplings and connections.”

If this is reality, then how can Sade be wrong? Why should children not be part of the pleasures on offer to what Deleuze regularly refers to the “desiring machine?” What is a child in any case?

At the risk of repeating a point I have made in a previous essay, it is worth mentioning that many of the most prestigious philosophers, authors (Jean-Paul Sartre (his book Nausea had used the character of an autodidactic paedophile as a tragic example of authenticity thwarted by a judgmental society), Simone de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Louis Althusser, André Glucksmann, Roland Barthes, Guy Hocquenhem, Alan Robbe-Grillet and Philippe Sollers) in France were signatories to a 1977 petition calling for the decriminalisation of all “consenting” sexual relations between adults and minors under the age of fifteen (the age of consent in France at that time). That same year also saw a public letter in Le Monde (January 26, 1977) on the eve of the trial of three men accused of having sex with 13 and 14 year old girls and boys, calling for the court to recognize the consent of thirteen year olds as they were treated as having legal responsibility equivalent to adults in other spheres of life.

In addition to the letter being signed by the figures above, it also included the signatures of Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Jean-François Lyotard, the surrealist poet Louis Aragon, Michel Leyris, the film, theatre and opera director Patrice Chereau, France’s future Minister of Culture and Education, Jack Lang, and Bernard Kouchner, who would become France’s Health Minister and a co-founder of Doctors without Borders, as well as various psychiatrists, psychologists and doctors. The signatories were, in short, the very cream of French society, and what the petition and letter showed were the priorities of the pedagogical and professional class.

The petition and letter are an early symptom of the same kind of priorities which bestow upon the child an urgent sense of its sexual identity and needs that is now exhibited within medical and psychiatric and school boards and legislative bodies in the US, and elsewhere. If a child is taught how to pleasure “itself” by being exposed to the kinds of pleasures available—from masturbation, to cunnilingus, fellatio and anal sex, through Sex Ed courses in schools and school library books—why should they not also decide whether they want the sex organs they have—and, of course, why should they not also take their sexual pleasure from an adult who is attracted to minors?

That last point is central to the cultural wars, which have reached such a pitch of unmitigated defence of the progressive class which wants to rear its children to be fully exposed to sexual needs and identity that it has responded to the recent film about child sex trafficking, The Sound of Freedom, by denouncing it as a right-wing, Q-Anon movie inducing mass hysteria.

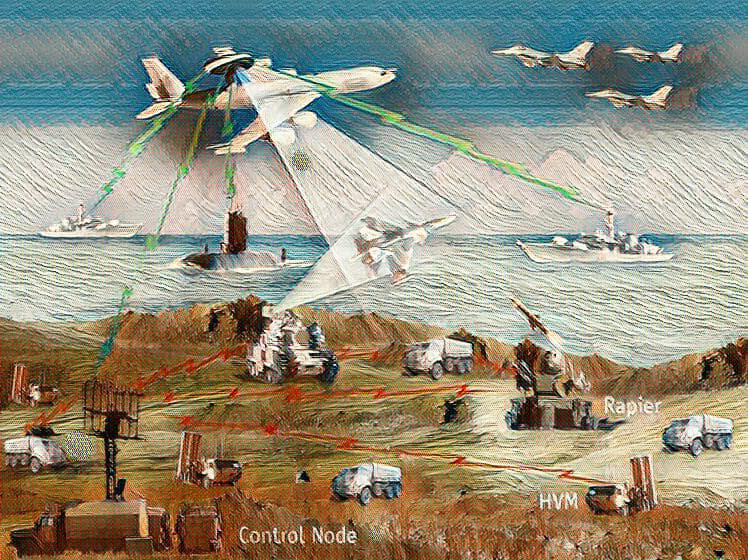

Not all the philosophers mentioned above who were signatories to the petition or letter saw themselves as mechanists, however all intellectually operate within the Godless view of world that gave birth to modernity and whose two philosophical poles can be traced back to Réne Descartes. Those two poles to the metaphysics of determinism (everything can be strictly understood as the result of mechanical causes complying to the laws of nature) and voluntarism (the will is the decisive source of our knowledge and hence our world in so far as it is knowable and in so far as we make it, in J.G. Fichte’s terms, a non-I that becomes the material for the fact-acts of the I). They are at the root of modern philosophy’s technocratic and ideological streams. They might on the surface appear to be radically opposed to each other. But just as in Descartes we find the two coming out of the philosophical mind’s desire to control the world to get what it wants—they develop in relative conjunction to each other, something evident in how swiftly the mechanistic metaphysics is deployed for political objectives. The two poles ultimately require cooperation involving the division of labour in which the scientists work focus on the material relations and resources to be hammered into place, while the ideologues administer the human resources (their sentiments, habits, values, organizations, institutions and classes) to be incorporated into the technological assemblage that is the world.

Let me state at the outset, that there is much to admire in Descartes, and that his philosophy is a response to the horrors of almost a century of religious wars in France and the Thirty years wars in which he fought. He was a man seeking a way out of hell. Unfortunately, he created the clearing for a new kind of hell, and just as Marx had no idea that he would be contributing a way of thinking leading to the mass murder of the peasantry (how else could their private property be expropriated if they wished to keep their land?), Descartes may have been astonished to think that what he intended to be so helpful may have turned out to be so diabolical.

1. Descartes and the Metaphysical Foundations of the Modern World

In the annals of philosophy I think no passage has been more fateful than this seemingly innocuous section from the sixth of René Descartes’ Discourse on Method, a book written in the vernacular and for the educated public who might be interested in developing his ideas further.

But as soon as I had acquired some general notions respecting physics, and beginning to make trial of them in various particular difficulties, had observed how far they can carry us, and how much they differ from the principles that have been employed up to the present time, I believed that I could not keep them concealed without sinning grievously against the law by which we are bound to promote, as far as in us lies, the general good of mankind. For by them I perceived it to be possible to arrive at knowledge highly useful in life; and in room of the speculative philosophy usually taught in the schools, to discover a practical, by means of which, knowing the force and action of fire, water, air the stars, the heavens, and all the other bodies that surround us, as distinctly as we know the various crafts of our artisans, we might also apply them in the same way to all the uses to which they are adapted, and thus render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature. And this is a result to be desired, not only in order to the invention of an infinity of arts, by which we might be enabled to enjoy without any trouble the fruits of the earth, and all its comforts, but also and especially for the preservation of health, which is without doubt, of all the blessings of this life, the first and fundamental one; for the mind is so intimately dependent upon the condition and relation of the organs of the body, that if any means can ever be found to render men wiser and more ingenious than hitherto, I believe that it is in medicine they must be sought for. It is true that the science of medicine, as it now exists, contains few things whose utility is very remarkable: but without any wish to depreciate it, I am confident that there is no one, even among those whose profession it is, who does not admit that all at present known in it is almost nothing in comparison of what remains to be discovered; and that we could free ourselves from an infinity of maladies of body as well as of mind, and perhaps also even from the debility of age, if we had sufficiently ample knowledge of their causes, and of all the remedies provided for us by nature…..

But in this I have adopted the following order: first, I have essayed to find in general the principles, or first causes of all that is or can be in the world, without taking into consideration for this end anything but God himself who has created it, and without deducing them from any other source than from certain germs of truths naturally existing in our minds In the second place, I examined what were the first and most ordinary effects that could be deduced from these causes; and it appears to me that, in this way, I have found heavens, stars, an earth, and even on the earth water, air, fire, minerals, and some other things of this kind, which of all others are the most common and simple, and hence the easiest to know… turning over in my mind… the objects that had ever been presented to my senses I freely venture to state that I have never observed any which I could not satisfactorily explain by the principles had discovered.

Descartes always delivered the most breathtakingly novel ideas in a combination of sardonic wit, self-effacement and false modesty, and the Discourse is a rhetorical masterpiece in philosophical irony, as he entices his readers into joining him in forging the new world that lies before us if we but follow his method, while at the same time conceding, that his own talent is but mediocre and his ideas may be but “a little copper and glass,” which he mistakes for diamonds and gold. He has simply made use of the natural reason which all of us have, and with that little bit of reason he has discovered a philosophy that cannot only be applied via experiments to eventually explain everything in the world, but we will be able to live in comfort as we live off the fruits of the earth put at our disposal by labour saving devices—and we might be able to live forever.

The idea of creating a new world did not begin with Descartes—Bacon had already written the New Atlantis some eleven years earlier and, like Descartes, Bacon had dreamt of science opening up the pathway to a new future. But whilst Bacon believed in the importance of experiment Descartes had reconstrued the entire universe so that it complied with a method he had uncovered in part thanks to the metaphysical principles which guaranteed a law-governed universe—for that is what he finds in the innate idea of God, a guarantee that the universe will not play tricks on his mind if he proceeds aright. God is perfect and he is not a deceiver, which also means, as I will pick up again below, that the universe runs according to impermeable laws.

What Descartes envisages is a universe in which all relationships are physical and causal and are spatially arranged—everything is an extended substance, everything except the cognitive operations of the mind-soul (he equates mind and soul, as if this were simply the most natural equation in the world to make) whose function is to identify the requisite method for studying the causal connections between the machine components. Being extended the bodies in motion, ever impacting upon each other, can be geometrically represented. The importance of analytical geometry (number can be represented as figure and vice versa) in Descartes’s corpus was such that his book Geometry was published with the Discourses.

As with Galileo, Descartes believed the book of nature was written in number. And while it is true that his own experiments often ignored the primacy of number, for Descartes being able to dissolve bodies into figure and number gave them the stability that could ensure their manipulation. Unlike sense data which was invariably confused and needs to be better understood—e.g., the sun looks small, and only when we take cognizance of its distance from us can we form a more accurate picture of its proper size—mathematics allows no room for sensory distortion. Mathematics provides us with the most clear and distinct ideas that we can have, and hence in a world of confused sensations, to present the truth as number/figure is to represent the undistorted truth. The truths of testimony, witness, the panoply of truths of the human world, the truths that are historically and culturally revealed, are all dissolved into the vast spatial plenum that is before the eye of the observing subject armed with the Cartesian method.

The great hyperbolic doubt that Descartes enters into before coming out of it by virtue of the rock certainty of him being a thinking being, and thereby moving onto other ideas whose certitude can be identified is like a vortex in which all cultural and historical truths are swallowed up, only to be released if they themselves are capable of being confirmed by the method of analysis and synthesis, and it is with this method, as well as the objectives of its deployment, Descartes launched the Enlightenment. In fact, as we shall see further below, it is also the initial onslaught of what will eventually be the overthrow of Christendom—both of the beliefs and narratives (the ‘ideas’) that hold it together as well as the values that it had cultivated for so long. The preparation for that onslaught is prepared culturally by the new metaphysics and politically comes to fruition in the first anti-Christian revolution since the establishment of Christendom, the French Revolution in which idea of liberty, equality and fraternity replace the Christian virtues as the scale of social, civic, and political importance.

The method of analysis and synthesis, the breaking down of bodies into their simplest parts and then reassembling those parts in order to identify the causal mechanisms at work in a particular phenomenon—the phenomenon is really the epiphenomenon, and the causal mechanisms are responsible for it appearing the way it appears. However, once we identity how the things of the world work, we are better placed to discovery ways that may help us improve our conditions. The mass social deployment of scientists using laboratories to invent new cures, “machines,” and technologies is the great forest seeded by Descartes slim philosophical volumes.

The application of that method requires, as is evident in his works on Optics and Meteorology, that one must make models of the bodies to be studied in order to derive the laws governing their interaction. The making of models involves the use of the imagination. But it is the imagination in service to the faculty of ‘the understanding’ whose task is to coordinate and organize the data presented to the senses which is invariably deceptive via the method he supplies so one can identify the regularities of what Galileo had already identified as primary qualities, and thereby focus upon them as the causes, as opposed to the secondary qualities, or mere epiphenomenon.

In the pre-Galileo and pre-Cartesian world where Aristotle still reigned, bodies had specific qualities such as lightness or heaviness, dampness or dryness, heat or coldness and such like, and hence the study of Physics proceeded by investigating bodies on the basis of those qualities, and making generalizations about them. The great break-through in Physics came when it is was realized that the underlying agitations, motions, repulsions and attractions, velocities and masses held the key to physical properties and the laws that governed them.

Ernst Cassirer in his Theory of Knowledge has pointed out that what distinguished Bacon from Descartes, was that while both saw Aristotle as the great stumbling block to physics (Galileo also made little secret of his hostility to Aristotle, and paid the price for it), Bacon still proceeded experimentally along Aristotelian lines, while Descartes dissolved the world of senses into the motion of bodies that could be geometrically and numerically represented.

As I have indicated Descartes was, up to a point, following in the footsteps of Galileo. But as the above passage illustrates, the real innovation of Descartes was (analytic geometry aside) not so much in the specific scientific discoveries he made, and the reason he is still studied today in universities, and why he is the grandfather of philosophism as technocratism, is his expansion of the significance of the ideas coming out of developments in astronomy and physics going back at least to Copernicus, and providing a metaphysics, a view of the entire universe, which would enable us to literally start again and turn the world—and by world he meant the universe—into an object for us subjects. The task is a grand one indeed. It requires an army of researchers pooling their results so that one day they may truly be able to make of the world what they will, which as the passage above suggests would be a more comfortable world. As is typical of Descartes, the rendering of philosophy into what is essentially a utilitarian enterprise in which we study the world to achieve greater comfort, the radical nature of the meaning he ascribes to this new philosophy is passed over as if it were of little consequence.

To be subjects—i.e., the potential lords and possessors or masters of the universe—required cognizance of the method to be deployed to make us so powerful. It is the importance of that method that is behind what is to this day still thrown out to philosophy undergraduates as a major mystery in which Descartes has two substances—body and mind—and a metaphysics that can readily be resolved if it were merely appreciated that there is no mind as such, which so the argument goes is where Descartes went awry. The mystery of Descartes’s dualism does not preserve though, if one pays attention to what he says and does rather than to the more traditional meaning of the soul as a thing or substance in the Platonic, or Christian traditions (even allowing for the fact that the Platonic and Christian soul are also not the same thing).

Descartes uses the language of substance to describe the mind, thereby giving the impression it is a “thing.” But the entire division between mind and body is to distinguish between what are cognitive operations and what has spatial extension. The point of Descartes drawing philosophical attention to the cognitive functions is to dispel the false way of thinking in which sensation overpowers the understanding and the imagination becomes overpowered by sensations which leave our minds caught up in the confusion that his philosophy was designed to dispel.

When Descartes’ “student” Father Malebranche writes, “Imagination is a lunatic that likes to play the fool. Its leaps and unforeseen starts distract you, and me as well,” he is being a diligent student of Descartes, the same is the case for Spinoza’s various disparaging comments about the imagination. Reigning in the imagination, and making it a servant of the capacity to understand is the decisive undertaking of the Enlightenment launched by Descartes. Indeed, the importance of identifying the operations of the mind and soul is inseparable from using a method for properly conducting one’s reason—i.e., properly conducting one’s reason means not being misled by the senses and the imagination. Now the point of this is that it would be meaningless—what the 20th century philosopher Gilbert Ryle would call a “category mistake”—to speak of method in the same language as one addresses extended substance. The division between mind-soul-cognitive functions-method and extension-bodies in space-nature-what we know thanks to the application of the method is total and being total Descartes can say he has proven that the mind does not die: it does not die because it is not a substance in the same way that a body is, but the dummies (for Descartes his enemies really are dummies) speak of it as if it is. It is a substance precisely in the terms that Descartes says it is—and it is purely a combination of operations, whose purpose is to have clear and distinct ideas about the world so that we can master it.

Now, as is clear in the Passions of the Soul, we can indeed talk about the mind impinging upon the body and vice versa. But that is not when we are speaking about rightly conducting our reason according to a method. When though we want to carry out a bodily action in accordance with an idea of the mind we are now in the land of a mind in union with a body, and the only way that union can take place is mechanically/corporeally, which is why Descartes believed he had located the point of union in the pineal gland. Irrespective of the particular location, the Passions of the Soul is an utter physicalist account of the soul-mind. It is a pioneering work in behavioral psychology in which, just as in Psychology courses today, we are introduced to the idea of the brain being divided into various parts which serve different mental functions.

In other words, and to sum up at the risk of repetition, just as Descartes’s philosophy is dualist—it provides a method based upon the operations of the mind-soul, and it presents observations about the world (the extended substance) based upon that method, it also provides a dualistic account of the mind-soul: in one the mind-soul is a bundle of cognitive operations, which will be taken up by philosophers from Locke to Kant, who will follow him and develop a “logic” (i.e., they will try to identify the various “elements”) of the “faculties” of the mind, in the other it is essentially the brain. The questions one is asking will lead one to one or other—if I ask how should I generally proceed to understand some phenomenon of nature I am led to consider the mind as a substance having no connection to the extended world which I wish to survey; if I ask why can I no longer speak after an accident, or even how is the mind involved in talking or seeing, even in identifying forms, colours etc. then I am in the realm of extension, and have to investigate the brain to understand what is transpiring within the mind.

Philosophers who commence with Descartes’ arguments for the existence of God and the soul, or who rip these arguments out of the larger cloth of his philosophy invariably ignore (a) how his philosophy introduces new content into these two names and (b) where they fit into the larger purpose of his philosophy of freeing us from the confused imaginings that we have made of the sensations we have accepted as true because we have hitherto not properly understood them.

The metaphysics especially as presented to the schoolmen in the Meditations may appear traditional, but what is done with it is as untraditional as the aims of the philosophy are. Apart from the fact Descartes says in various letters that he is advancing his teachings behind a mask, that he is pouring new wine into old bottles, that he only spends a few hours a year on metaphysics, and apart from the even more obvious fact that his attempts to seduce the school men still pre-dominating in the universities in France did not work, at least initially, and that the Catholic Descartes was far freer and safer in Protestant lands, it is the content of his metaphysics that shows just how remote from anything traditionally Christian his philosophy is. Indeed, that is nowhere more obvious than when Descartes is presenting himself as most “orthodox” as he wants to prove the existence of God and the soul (and of the soul I have said enough).

Although Christian philosophers, commencing most famously with Anselm, had long since been sufficiently influenced by Greek philosophy to make an argument for God’s existence, thereby making him commensurate with our God given powers of reason, traditionally God’s existence is based upon testimony not demonstration. That is the required reading for understanding God’s ways and deeds is the bible not any work by a theologian. That becomes of fundamental importance when we inquire into the deeds of God as opposed to merely wishing to satiate our intellectual curiosity over the question whether God exists.

Generally scholastic philosophy uses reason to try and mediate between seemingly contrary passages in scripture. The problem of scriptural contradiction was thrown down by Abelard, and the most all-encompassing attempt at a major resolution was Aquinas’ Summa Theologica. Luther’s animosity to Aquinas would be due to what he saw as a deranged concession to paganism that elevated reason far above its station. Irrespective of Luther’s critique, Aquinas was more interested in reconciling reason and faith so that reason could not tear faith apart, rather than simply making reason the pilot for scouring the all-encompassing totality of the universe. Aquinas respected Aristotle, for Aristotle was an intelligent seeker of truth, but the truth that offered salvation was a revealed truth. Thus too, for example, Dante must leave Aristotle in the first circle of hell—which is actually not that unpleasant, but dwelling there is to be dwelling in a condition where one has been satiated by one’s own intelligence more than God’s grace.

With Descartes God’s grace is completely irrelevant as indeed is prayer, or indeed any kind of personal relationship. God is an idea, an innate idea of reason to be sure, but an idea of perfection that offers the promise of Descartes and those who join him eventually being able to understand the universe. The traditional understanding of Christian salvation simply has no place in the God of Descartes. Pascal would put his finger on the central issue when he said, “I cannot forgive Descartes. In his whole philosophy he would like to dispense with God, but he could not help allowing Him a flick of the fingers to set the world in motion, after which he had no more use for God.” God serves a function in the larger project of philosophical understanding by providing a metaphysical reason to accept a law-governed universe—and without that principle the entire Cartesian-modern scientific enterprise is useless.

We should note also the primary take away that Descartes has in focussing upon God’s perfection, viz. that God does not deceive. This gives Descartes the go ahead to carry on studying nature in accordance with the method of analysis and synthesis, in spite of the delusionary nature of the appearances that leads him to undertake his hyperbolic doubt. He has used theology to make a metaphysical claim in a system that, apart from its underlying metaphysic and the method which he lays down, could eventually give us knowledge of everything.

With respect to the claim that God does not deceive, there are indeed scriptural references to God never lying e.g., Hebrews 6: 18: “[it is] impossible for God to lie,” Titus 1:2: “God, who never lies.” Yet God also puts “a lying spirit in the mouths” of unrighteous prophets (1 Kings 22-23; 2 Chronicles 18:22), and in 2 Thessalonians 2: 8-12 we read:

Then shall be revealed the Lawless One, whom the Lord shall consume with the spirit of his mouth, and shall destroy with the manifestation of his presence, [him,] whose presence is according to the working of the Adversary, in all power, and signs, and lying wonders, and in all deceitfulness of the unrighteousness in those perishing, because the love of the truth they did not receive for their being saved, and because of this shall God send to them a working of delusion, for their believing the lie, that they may be judged—all who did not believe the truth, but were well pleased in the unrighteousness.

As this passage, and indeed all the passages cited indicate, the matter of God’s veracity or willingness to have the lies and deceit of the unrighteous be turned against them has absolutely nothing to do with what it is Descartes is seeking, viz., confirmation that the world is not created by an evil genius but conforms to laws laid down by a perfect being. But rather the matter of God’s veracity as it is broached in the bible has to do with the relationship between Him and His people, his believers. It is a matter of the veracity of the word, but Descartes’s philosophy has no real interest in the word as such, nor in any covenant with God, nor in eternal salvation.

Kant, who is the beneficiary of more than a century of metaphysical disputation will demonstrate why Descartes’ and indeed any other ontological argument about God’s existence defies our knowledge, and hence why God is only a “mere idea,” which for knowledge may serve a heuristic idea for faith in the systemic unity of our knowledge. Unlike Descartes he disengages the idea of the world-universe being a totality of laws from the existence of God, by making the cognitive components involved in the formation of knowledge the source of law. That is, he is even more consistent than Descartes himself in his elevation of the role of the subject in the acquisition of knowledge. And further the idea of God is retained only to the extent it is a matter of rational faith—not knowledge as such. But in this as so much else Kant simply has a more profound understanding of what a law governed universe along strictly causal principles must mean than Descartes who is simply using the metaphysics to get to the real work of science, and in doing so attempts to draw the faithful into a new, and far more restricted, far more rational understanding of God as a perfect being.

Unintentionally—and to his ire, because he was witness to the early developments by Fichte and the young Schelling in this direction—Kant had inspired the birth of the romantic approach to knowledge in which the “I” is not simply, as in Descartes, the basis of a proper foundation for gaining knowledge to master the universe, but the source of its making, for nature in itself is but the I writ large (this will be a step too far for Schelling who retrieves Spinoza in his battle with Fichte).

But tarrying with Descartes, his talk of God not being a deceiver ultimately leads to a claim that simply must be the case if Descartes’ philosophy is followed consistently. And it is a claim that he would only disclose in his book The World, a work that appeared in print only after his death, viz., that there are no miracles. If there were miracles then God would be intervening and thereby disrupting the infinite causal chain that makes the world the way it is.

Those who want to take Descartes at his word and see his demonstration of the proof of the

existence of God and the soul as acts of a pious man are stuck with the fact that their man of piety has completely changed the nature of God to fit his idea of who and what God is. One may think that is terrific, but it cannot be passed off as either Christian or Catholic in any traditional sense.

Christianity is based upon the centrality of the miraculous in our lives: from the miracle of creation itself, to the miracle of the triune God, to the miracle of God sending his Son to redeem the world, to the miracles that Jesus performed on earth, to the miracle of the resurrection, and indeed to the miracles that transpire in our everyday life thanks to God’s grace and the Holy Spirit. Irrespective of the fact that some philosophers who lauded Descartes such as Father Malebranche believed his philosophy was compatible with their faith, there is simply no way of bypassing the issue that Descartes’ Deism—and indeed all subsequent deists—are introducing an idea of God that has no place left for any of the most important teachings of the Christian faith, whether that be a personal loving triune God, or a God that so loves the world that he sends his only begotten son, or that his son performed miracles on earth and was resurrected.

This was the grand take away from a philosopher who was so determined to rebuild the world on the basis of clear and distinct ideas that he went in search of the indubitable, and that indubitable starting point was not as it is for Christians, faith itself, but his own thinking. That was, as has often been noted, a variation of an argument originally made by Augustine, about the impossibility of refuting that one is a thinking being when one is thinking. But Augustine uses that doubt to then move to a God who does not simply dispel his doubt but gives his life a mission and purpose—Augustine serves his God because his God saves him from sin and offers him redemption. Such a God has nothing in common with a God who is an innate idea and not a person. Likewise, the self of Augustine is not akin to the Cartesian self. The self in the Christian tradition is not a fulcrum for building a universe, but a dependent, fragile and sinful creature caught twixt the flesh of its “warring members” and the soul’s salvation that may be granted by God’ s grace. For Christians all souls have the prospect of redemption open to them by virtue of God Himself being the sacrifice.

The world in which the followers of Luther and Calvin did battle with each other as well as with the Roman Church was one in which the seemingly smallest differences concerning interpretation of a piece of scripture, or the ritual of the mass, or even the appearance of the Church, and even larger differences such as the role of the priest-preacher, how the body of the faithful should be organized and practice their rituals, which prayers they should say or sing, which parts of the Bible might need to be withdrawn because they were “false” and so on were matters of such extreme importance that they would even trigger men to make war with each other.

The young Descartes, as mentioned above, had himself fought for three years, initially signing up with the Protestant Prince, Maurice of Nassau, in the war that had been the culmination of religious wars. I think it impossible to ignore the importance of that war which wreaked such devastation in Europe as playing a major part in the formation of philosophical deism, as a way of bridging confessional divisions within Christendom. Moreover, philosophical deism of the Cartesian sort was but one attempt to create a synthesis of religion and science. A more occult variety, which Descartes was aware of, existed in the writings of the members of the Fraternity of the Rosy Cross.

Descartes’ early biographer Adrien Baillet mentions that Descartes unsuccessfully tried to contact them. Though it was questionable whether outside of such writings as, The Confession of the Rosicrucian Fraternity (1615), and The Chymical Marriage of Christian Rosenkreuz (1616), there was any actual fraternity—it was rumoured that its members were chimerical, which, as Descartes reasoned, would explain why he could not find them. As I pick up below the development of secret societies in Europe, particularly the Free Masons and Illuminati, would play an important role in spreading ideas that deviated from Christian doctrine whilst being far more compatible with the kinds of theological ideas that accompanied the new metaphysics.

2. Anti-Cartesian Metaphysics in Spinoza, Locke and Kant

With respect to the larger cultural and intellectual landscape in the aftermath of Descartes’ metaphysics, in spite of the plethora of metaphysical disputations about what God and the soul are and do, whether space, for example, is an organ of God (Newton and Clarke) or not (Leibniz), the analysis of clear and distinct ideas which can enable us to identify the inviolable mechanical laws which constitute the world and our experience as properly identified by the understanding is a constant. And the division between what would become known as the dispute between rationalists and empiricists is not about whether one group is genuinely dispensing with the use of reason in making inferences to the extent that experiment is not warranted, but the extent to which experiment is dependent upon principles, including mathematical ones.

This is, though, another way of also saying that all post-Cartesian metaphysics, whether the raw materialism of Hobbes, the pure idealism of Berkeley, the dogmatic empiricism of Locke, the parallelism of Spinoza, the ‘panlogism’ of Leibniz, or the transcendental idealism of Kant (which is an attempt to reconcile all by showing the point up until which they are right and where they then go wrong) make reason and its comprehension of the laws of nature the touchstone of truth. Some of these philosophers, like Spinoza, Hobbes, and Leibniz see a miracle as either a word for what has not been properly understood, or, what is essentially the same thing something explicable via natural and scientific means.

Others who are outspoken defenders of the faith like Locke, Berkeley and Malebranche also see the new philosophy as consistent with occasional miracles. While a work such as Locke’s The Reasonableness of Christianity, a work largely consisting of biblical references lends support to what seemed to be his public attack upon deism, a more cautious reading as provided by Cornelio Fabro in a book I consider to be the most masterful examination of the philosophical roots of modern atheism—God in Exile: Modern Atheism, A Study in the Internal Dynamics of Modern Atheism, from its roots in the Cartesian Cognito to the Present Day, makes the compelling case that confirms the total cleft between what Pascal delineated as the God of the philosophers and scientists, and the God of Abram, Isaac, and Joseph.

Fabro calls Locke’s theology a “Deism of the right,” which, as Fabro indicates, is a defense of Christianity that does claim that scripture and Christianity are true—but that is only to the extent that the truths revealed are what Locke the philosopher identifies as reasonable. As the very title mentioned above of Locke’s major work on the topic, this requires contingency to be reasonable. But human stories are not strictly the result of mental inferences, they involve encounters. And encounters are contingent, particularly meaningful ones might be called miraculous. That is not because the miraculous is reasonable (Locke’s argument for why we should accept miracles), but because the meaning of the encounter is of such a magnitude that we can only attribute its occurrence to God’s grace. And God’s grace has nothing to do with what our reasons make of it.

In keeping with the reduction of Christianity to a rational religion, Christianity in Locke’s hands is, as Fabro rightly points out, the same as we find in Kant, a natural religion and ethic. As Locke puts it in The Reasonableness of Christianity, Christ “inculcates to the people, on all occasions, that the kingdom of God is come: he shows the way of admittance into this kingdom, viz. repentance and baptism; and teaches the laws of it, viz., good life, according to the strictest rules of virtue and mortality.” Try making sense of the redemption of the thief on the cross by resorting to “the strictest rules of virtue and morality.”

The centerpiece of Locke’s thought, and where he hopes not only to correct the faulty metaphysics of Descartes, but to establish once and all for the nature and limits of “the human understanding” is his sense perceptionism, and as Fabro points out later English deists such as Collins, Dodwell, Coward, Hartley, Priestly, and the rest, were to sweep away the last theological restriction adhering to Locke’s sense-perceptionism.

Irrespective of the particular emphasis of any of the post-Cartesian metaphysicians they all concur that whatever mental constraints there are upon us will need to come from reason itself, and where God is invoked it is the God of philosophers. This, though, is predicated upon another element of faith that contravenes the Christian tradition, viz. it dispenses with original sin, at least as far as reason is concerned, and it also radically reconfigures value.

That reconfiguration is played out through various influential philosophical positions, and invariably they involve disputation.

I will just mention a few that have enormous consequence in ensconcing what we now live within, a hybrid culture of a mechanical understanding of what humans are (and hence how they can be technologically superseded) and an idealist value system in which dignity (respect), equality (equity), freedom (emancipation) and the like are invoked to legitimate the world we are making and our behavior in it.

Descartes himself had initially indicated that the new philosophy would provide the content for ethics, and that his philosophy had opened up the prospect of humanity finding a new dwelling, though he was quite content to counsel obedience to customary authority—implying as he did so that those authorities and those customs might not be deemed consistent with reason’s natural light.

Spinoza was Descartes’ most openly radical student, and anyone who doubts the extent of his intellectual influence in attracting readers to a more enlightened and non-Christian view of society should read Jonathan Israel’s Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650–1750, and his more recent, Spinoza, Life and Legacy. Whereas Descartes was cautious, Spinoza was bold—even Hobbes (whose Leviathan is a mechanistic account of the political body and the source of sovereignty), is reported in the brief biography of him by Aubrey to have exclaimed when reading Spinoza’s Theological Political Treatise, “I durst not write so boldly.” Spinoza uses the principles of the new philosophy to write an Ethics, reimagine the structure, and purpose of the state, primarily so that it may function in order to protect the work of philosophers and scientists like himself. He would also argue that the bible was a collection of myths, whose true grounding and history would reveal what a human-all-too human book it was.

Spinoza is invariably taught in Philosophy classes as a metaphysical opponent of Descartes. But such a reading magnifies the metaphysical differences between the two (Spinoza is a monist, not a dualist, and allows no scope for the free will—though the free will in Descartes is also just a cognitive operation of acceptance or denial of the information to be incorporated into one’s understanding about the material being studied) to the extent that it smothers the far larger affinity of the purpose and rationale of establishing the metaphysics. And, as with Descartes, it is to render the entirety of nature as one vast body of laws which the philosopher-scientist (at this time a scientist was still considered to be a “natural philosopher”) will study in order that we live better. Like Descartes Spinoza allows no room for miracles, for that would require departing from a strictly causal chain of bodies/powers.

Most radically Spinoza would simply dissolve God into nature. Strictly speaking Spinoza is a pantheist, rather than a deist, but in the bigger picture of cultural transformation that is merely a moot distinction of importance of philosophers, but not to how religion figures in life. Also, of great importance in the subsequent transformation of European culture was the claim in Spinoza’s Ethics that pleasure is the good, and pain the evil. Utilitarianism—which forms the basis of modern economic thinking—takes off from this position, and the self simply becomes a pleasure maximizing agent.

Sade was, to pick up on my earlier point, the most transgressive and unrestrained because he took pleasure in pain, both receiving it and inflict it—his thought was the consummation of a mechanistic view of life in which pleasure in its most extreme forms is the purpose of life.

To be sure, one would find it difficult to find a character less like the debauched Sade than Spinoza, and Spinoza’s Ethics is a work devoted to improving the human understanding, so that improvement of one’s understanding by being attentive to nature and its laws, and living in accordance with what the mind has understood is virtue itself, and that is the genuinely pleasurable life. But to a Sade, Spinoza simply seems too tame, unable or unwilling to throw everything into the furnace where life and death are all part of the same tumult of appetites, drives, and desires that are intrinsic to a cosmos which endlessly begets and devours life itself—and is evil. By embracing evil Sade takes his revenge on the cosmos by playing and embracing the game of endless extinction, by taking joy in it. The cosmos is evil—and so is Sade.

If Spinoza had laid down an ethic in which freedom is simply living how we must, as our lives are determined, Kant’s philosophy would pick up on the more normatively developed claims that were intrinsic to the those politically inflected philosophies which were appealing to rights. Whereas the arc from Spinoza, Hobbes and Bentham saw rights, and the natural law theories they derived from, as simply surrogate words for power, or as Bentham put it bluntly “nonsense on stilts,” Locke, and Rousseau, albeit in different ways, were making “rights” the basis of their respective critiques of traditional, i.e., monarchies invested with prerogative power, political orders they wished to be rid of.

Kant’s moral theory would have political implications—all constitutions should be republican, but he saw the larger problem of mechanism in its view of human beings as lacking freedom and thereby any moral purpose, or dignity. If morals are but powers, as they would be if we are but links in a great causal chain, then all we are talking about is force. Kant sought to defend moral right, and human dignity, by locating their source in reason itself. To this end his philosophy is genuinely dualist, and even more consistently and rigorously so than Descartes’ (though he does attempt to explicate how the faculty of judgment—in matters of biology, art and ideas about moral progress—serves to mediate between the phenomenal [what can be experienced and hence known] and noumenal [what is but the mind’s own rational creation]).

Kant’s dualism consists in arguing that the nature and legitimate scope of the elements of the mind’s forms and functions—the gathering of knowledge and the creation of moral ideals—can be strictly identified. Philosophers have heretofore failed to recognize that the elements of cognition that have an indispensable function in enabling our sensory representations to become knowledge have taken on a false reality thereby deluding us into thinking we have knowledge of God, the immortal soul, and moral freedom—all of which are but ideas that come from the faculty of reason’s own operations. They are not objects of possible experience, and not being so, we cannot disprove their existence. We can identify that they serve a moral purpose and thus we may accept these ideas as forming the basis of a rational faith.

I do not want to go into the details of Kant’s flawed arguments except to say the elements Kant insisted were unassailable all became assailable within the next century. More specifically, developments in geometry and logic rendered the Euclidean nature of space and time (the bedrock of his analysis of the a priori elements of the faculty of “intuition”), and the Aristotelian logical elements he thought settled that had provided the key to his table of categories of the “understanding,” as superseded. Kant’s constructivist theory of mathematics, which had to be true, for the rest of his theory of knowledge to work, convinced none of importance then or later. The very next generation of post-mechanistic metaphysicians were done with the strictures of Descartes and the investigations of those who “led” to Kant.

But, irrespective of the adequacy of Kant’s argument, his claim that the rational nature of human beings warrants that we should morally see ourselves as a member of a moral commonwealth, a commonwealth of ends and not means and thus deserving dignity and respect has subsisted along with a view of selves as driven by appetites is conspicuous in how readily the contemporary mind flicks a switch between rights and respect talk to talk of pleasure, appetites and determinations. The contradictions of an age or group do indeed provide the key to their motivations and priorities. Kant’s dualism is also built upon his recognition that our empirical selves are prone to what he would call radical evil, which simply meant for him, our propensity to have our moral principles tainted by our desires and drives. On the surface, this seems to be Kant’s rational concession to the Christian doctrine of original sin—except it is not. It is his way of making reason itself impervious to appetite—so that if we but apply the moral imperative to any circumstance we at least know what we should do.

The problems with the categorical imperative were exhaustively demolished by Hegel who notes that no example provided by Kant does not already draw upon the communal value in the sheer nomenclature and indeed in the very examples themselves of what constitutes a moral dilemma. Kant’s account of “practical reason,” or moral theory, is predicated upon him having adequately delineated the “bounds of experience,” by establishing which elements of reason are essential for perceiving, judging, and making inferences about experiences, and then which kind of claims are not strictly beholden to those elements, but to what reason itself supplies as ideas of its own making that do not contravene the requisites of experience: God, soul and freedom, he says don’t, because they are “mere ideas of reason.”

On the surface, by arguing that our moral claims are but judgments expressing what we all ought to do (categorical imperatives) and accepting that one can never rule out the impure motive of why someone is appealing to the imperative it may look as if Kant is simply recognising that we can only ask of reason that it helps us aspire to our ideals. And that is a good thing, surely? But frankly Kant only muddies the waters by having such an absolute severance between ideal and motive. If we are prone to radical evil then why bother thinking our morals suffice to make us God-like? Kant also claims that a just constitution that simply requires we observe the laws, irrespective of our motives, is a good thing. Kant once famously framed the task of politics as creating a constitution for even a race of devils, forgetting to account for the fact that those who administer it would still be nothing more than devils, and thus use the constitution for diabolical gains. The constitution of pure reason is but an occasion for diabolical interests to act behind the idealist smokescreen of the delusions of those satisfied by their own reasons and gullibility.

The technocratic vision of being lords and masters of the universe might seem to have been based in the pursuit of knowledge alone, but it was inevitably a political vision. And while Rousseau and his epigone, including Kant, thought they could ensure a politics of moral rectitude if they but redesigned our institutions so that liberty and equality and the general will would prevail, there were a few insurmountable problem—humans just aren’t that good, and nor are their reasons that compelling when it comes to trying to get agreement. The French revolutionaries justified their behavior on the basis of their reasons, and what they delivered was civil war, terror and the creation of the greatest military regime on earth at the time. Ideas and reality, what we want and what we do—they refuse to match up.

3. Concluding Note on Philosophism and the French Revolution

Augustin Barruel’s Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism is one of the most brilliant critical accounts of the French revolution ever written—Edmund Burke was one of its admirers, and as someone who regularly used to teach Burke’s Reflections of the Revolution in France, I think Barruel’s a far more important work. It is often disparaged as being but the father of modern conspiracy theory thinking. That is primarily because Barruel documents the involvement in the revolution of the French Free Masons—an involvement that few historians of the French revolution say much about, even though pretty well all are aware of the fact that the lodges along with the salons and political clubs were a major place of political intrigue and discussion—and, as well, the Bavarian Illuminati.

At much the same time as Barruel was writing his book, the former Mason and Scottish natural philosopher John Robison had written his Proofs of A Conspiracy Against All the Religions and Government of Europe Carried on in the Secret Meetings of the Free Masons, Illuminati and Religious Societies Collected from Good Authorities. Both books are meticulous researched and draw upon reams of quotations of writings and letters from Free Masons, and Adam Weishaupt (“Spartacus”) and other members of the Illuminati about the program and political involvement of the Illuminati and Masons. Both organizations adopted mythic foundations thus claiming ancient pedigrees.

Barruel also makes a convincing argument about how a number of key masonic beliefs and objectives have antecedents in the Manicheans and Knights Templars—which is very different from claiming as some modern conspiracy theorists as well as Masons think that there is a direct lineage going back to antiquity, and the secret attempt to control the world has been going on for millennia. While the Illuminati were happy to infiltrate the Masons, not all Masons were interested in revolution, indeed there were royalist Masons who seemed to have no idea of what subversive purpose the Masons could be serving. Barruel also emphasizes that the French and British lodges were completely different beasts and that the politics of the French lodges was far more radical. Barruel argues throughout that the Masons, at its highest levels, were an anti-Christian, as much as they were an anti-royalist, force. And, indeed, the supreme being recognized by the Masons is identical to the deism of the philosophers, as well as Robespierre and his faction. While Barruel and Robinson both see the Masons and Illuminati as pernicious social forces which circulated ideas that would contribute to the destruction of throne and altar, neither are saying that there were not other factors which made the revolution.

The various crises in France—its debt, its dysfunctional administrative and taxation “system,” the class antagonisms especially with respect to tax payment and avoidance, and various events of panic and violence that made the revolution—had little if anything to do with the Masons or Illuminati. But the secret societies provided forums of discussion and deliberation for those seeking to take advantage of the chaotic circumstances that enabled a new ruling class. I will not enter here into which particular moments Barruel thought involved conspiratorial machinations of the Masons or illuminati, but generally

Barruel sees the philosophes, most conspicuously Voltaire and D’Alembert whose works and correspondence he was steeped in and Montesquieu and Rousseau as playing the major role in generating the ideas that would hold sway in the revolution.

Today we would not usually think of a conspiracy taking place when philosophers in class rooms or in conferences openly talk about creating a utopia and overthrowing this oppressive society. Indeed, it is now seen as completely normal that people pay taxes to have people use the university as a platform for the radical overthrow of that society’s foundations and traditions. But when Voltaire and friends—that included Frederick the Great, who Barruel detests for his vanity and willingness to tarry so long with such explosive ideas—speak of overthrowing throne and altar they are generally aware that these are things that must be aired with circumspection and delicacy. And Barruel devotes much of his effort to bringing to light the more revolutionary ideas that are to be found in the correspondence of Voltaire and D’Alembert, the ideas of Montesquieu, Rousseau and the Encyclopedists.

While the professional classes involved in the revolution were as much responding to circumstances as creating new ones that invariably overpowered them, their decisions were also fueled by the heady concoction of ideas that had swept them together—and not too much later divided them in blood.

All of this notwithstanding, the role played in the French revolution by philosophy, not only in shaping the appeals and narratives of the revolutionaries but also in the drafting of the constitutions—was unlike anything that had ever preceded it. (Though philosophical ideas had played an important role in the American Declaration of independence, it is hard to make the case that the American war of Independence was primarily driven by philosophical ideas.) One only has to consider how Locke’s philosophy comes after the English revolution, while the most important philosophers whose names were invoked during the French revolution preceded it.

Surprisingly Barruel says nothing of Descartes in his Memoirs; and whilst he mentions Descartes in his Les helviennes, ou Lettres provinciales philosophique, there is no indication of the founding role of Descartes in the revolutionary ideas and spirit of “philosophism.” In part. Barruel’s silence on Descartes may be explained by the ambivalence in which Descartes was held by many after his philosophy came to become accepted within the institutions which had once been the fortress of scholasticism, as well as the royal patronage his ideas received from the later part of the seventeenth century. Thus, Stéphanne van Damme notes in his “Restaging Descartes. From the Philosophical Reception to the national Pantheon”: that in the second part of the Eighteenth Century, “Descartes ceased to represent a renegade” and was seen “as a representative of the Old Regime.” Van Damme provides a concise but important account of the role of princely patrons in helping the circulation of Cartesian thought. The following is a pertinent part of the story:

In a rare process, by surpassing the limits of aristocratic sociability, by moving into princely circles, Cartesian philosophy became a truly cultural phenomenon during the seventeenth Century. First, Cartesianism was integrated into noble educational practices. Thus, Rohault, the Prince de Conti’s tutor, and Jacques Sauveur, the Duke d’Enghien’s tutor, contributed to this aristocratic passion for Cartesian physics. The Prince de Condé’s Jesuit tutors led the way in teaching Cartesianism. In January 1684, the Jesuit father Du Rosel spoke of the philosophical education of the young Duke d’Enghien: “We continue to examine the questions of place and space. We read what the Principes of Descartes have to say on this subject, and what they can contribute to an understanding of the difference between the old and the new Philosophy.”

Another pertinent part of the story which is indicative of the ambivalence surrounding Descartes’ contribution to the Enlightenment, was the central weakness in his physics, and—weaknesses which were often connected with the metaphysics—most brutally exposed by Newton. Indeed the triumph of Isaac Newton’s physics meant the complete defeat of Cartesian physics. In Newton’s De gravitatione et aequipondio fluidorum, a paper written in 1666 on hydrostatics, a very large digression (about four fifths of the paper) occurs in which Newton provides a detailed critique of Descartes’ conceptions of motion, space, and body (a translation by the philosopher Jonathan Bennett can be found here.

It is worth citing the following passage which exposes how the deficiencies in the physics and metaphysics are of apiece:

We take from body (just as he (Descartes) bids) gravity, duration, and all sensible qualities, so that nothing finally would remain except what belongs to its essence. Will, accordingly, extension only remain? Not at all. For we reject additionally that capacity or power by which the perceptions of thinking things move. For when the distinction is only between the ideas of thinking and extension so that something would not be manifest to be the foundation of the connection or relation unless that be caused by divine power; the capacities of bodies can be rejected with this reserved extension, but it would not be rejected with the reserved bodily nature. Obviously, the changes which can be induced in bodies by natural causes are only accidental and not denoting the substance actually to be changed.

But if anything could induce the change which transcends natural causes, it is more than accidentally and has radically attainted the substance. According to the sense of the demonstration those only are being rejected of which body, by force of nature, can be void and deprived. But no one would object that bodies which are not united to minds cannot immediately move their perceptions. And hence

when bodies are given united to minds by nothing, it will follow (that) this power is not among their essentials. The observation is that this does not act by actual union but only by the capacity of bodies by which they are capable of this union by force of nature. As by whatever capacity belongs to all bodies, it is manifest from it that the parts of the brain, especially the more subtle by which the mind is united, are

in continual flux, the new ones succeeding to those flying off. And it is not lesser to take (off) this, whether regarding the divine achievement or bodily nature, than to take (off) the other capacity by which bodies in themselves are able alternately to transfer mutual actions, that is, than to force body back into empty space.

The decisive victory of Newton over Cartesianism—to put it in its most simple and stark terms—was Newton’s demonstration of the fact that bodies did attract and repel each other at a distance and hence that the strictures Descartes placed upon the contiguity of bodies was false, and his vision of the universe as consisting of a plenum filled with vortexes, it was a universe in which no space was not filled with matter. Newton would famously say in his Principia, “Hypotheses non fingo” (“I feign no hypotheses”). Those three words would suffice to render Descartes’ physics a monstrous concoction of rationalism not much better than Aristotle’s concoctions.

Throughout the 1730s and 1740s Voltaire entered into the “wars” between the Newtonians and Cartesians (most famously in his Lettres philosophiques Éléments de la Philosophie de Newton), as a champion of the empirical genius of Newton (and Bacon, and Locke) against the reactionary rationalist Cartesians holding back progress. Notwithstanding “the Newton wars,” Voltaire’s overall assessment of the value of Descartes indicates that in spite of the various errors made by Descartes, his importance in the making of the new world cannot be ignored:

He pushed his metaphysical errors so far, as to declare that two and two make four for no other reason by because God would have it so. However, it will not be making him too great a compliment if we affirm that he was valuable even in his mistakes. He deceived himself, but then it was at least in a methodical way. He destroyed all the absurd chimeras with which youth had been infatuated for two thousand years. He taught his contemporaries how to reason, and enabled them to employ his own weapons against himself. If Descartes did not pay in good money, he however did great service in crying down that of a base alloy.

I indeed believe that very few will presume to compare his philosophy in any respect with that of Sir Isaac Newton. The former is an essay, the latter a masterpiece. But then the man who first brought us to the path of truth, was perhaps as great a genius as he who afterwards conducted us through it.

Descartes gave sight to the blind. These saw the errors of antiquity and of the sciences. The path he struck out is since become boundless.

Voltaire’s tribute to Descartes’ importance is also echoed by Condorcet, who unlike Voltaire actually participated in the revolution, only unfortunately to be on the side of the losing faction of the Girondins. Whilst in prison, where he died, he wrote his Outlines of an Historical View of the Progress, whose “ninth epoch” bears the title “From the Time of Descartes, to the Formation of the French Republic.” Like Voltaire, Condorcet noted the errors of Descartes and sides with Locke, but, also like Voltaire, he praises him for the new path he opens up:

From the time when the genius of Descartes impressed on the minds of men that general impulse, which is the first principle of a revolution in the destiny of the human species, to the happy period of entire social liberty, in which man has not been able to regain his natural independence till after having passed through a long series of ages of misfortune and slavery, the view of the progress of mathematical and physical science presents to us an immense horizon, of which it is necessary to distribute and assort the several parts, whether we may be desirous of fully comprehending the whole, on of observing their mutual relations.

Thus it was that Descartes would, as Van Damme notes, be the third writer to be listed in the decree founding the Pantheon on April 4, 1792” and “in 1792, the monument of Descartes was deposited in a new musée des monuments français organised by Alexandre Lenoir, and cenotaphs to his honor and other great men’s erected in the garden, jardin Élysée, around the museum.” Van Damme makes much of Louis-Sébastien Mercier, a member of the Council of Five Hundred denouncing Descartes’ “Pantheonization.” What he neglects to point out, though, is that during this post-Thermidor phase of the revolution the rhetoric of the revolution remained whilst the attempts to stabilize its momentum was taking a far more conservative direction. Further, whilst Mercier had been a disciple of Rousseau and an anti-cleric, with his revolutionary fervour chastened by the bloodbath of the Jacobins, Mercier turned upon everything he saw as a source of the “terror,” and at the beginning of it all was “the free thinking “Descartes. By then Mercier was no less hostile not only to Voltaire’s attacks upon religion, but more generally to philosophy itself as a subversive power within the people.

Of course, the French revolution was predicated upon normative appeals, including patriotism, that have nothing to do with Descartes. But my point in this essay has been to focus on the mechanistic metaphysical pole of the bifurcated modern self. That other pole, as I have said, is the one of reason no longer simply studying nature’s determinations but conjuring ideas which provide legitimation for political and social authority. This pole is even more destructive of liberties than the technocratic, for those who insist that their authority is based upon the moral or ethical values that give them authority in deciding what we may or may not do invariably, originally in communist and fascist and now in liberal democratic regimes, attack any who question their decisions and policy priorities.

The ruling political class and the class that devotes itself to the accumulation of scientific knowledge form a bond in which the authority of the one class facilitates the authority of the other. The politics corrupts the science, and the science corrupts the politics. Together they make a world far more frightening than any produced by an evil genius. Together, they dissolve the soul into a bifurcation of machine and empty abstraction, in which the spirit of tradition and place are also rendered of no importance unless they serve the larger narrational purpose of an identity to be inserted into the design. In that design machine and norms are magically revived and unified. What has been lost in the transmutation is the soul.

Frankenstein’s Monsters is what we are in danger of becoming as we are but machines with ideals that dictate our identity—for anyone who is black, a woman, a gay, etc., who deviates from the script of what that identity should be is no longer defined by their identity marks, but by their betrayal of the essence and the narrative that has been dictated to those who have that essence by their political saviors. This is the rational moral faith that dictates how we should be in our world of pleasure and material satiation delivered by the world as a great calculative resource. It is the faith that has enabled the globalist progressivist view of life in which all the resources of the planet are to be managed and all traditions to be rendered redundant.

The world is an occasion for the profit and pleasure of those who are able to preside over the technocratic forces that do their bidding. Nietzsche had used the phrase “God is dead,” and Heidegger “the gods have fled.” But the living God never dies, and humans always find gods to serve. The god of one’s own identity is though one of the most pitiful that has ever been conjured. Descartes would, I think, have been horrified to see how thoughtless the new thinking subject is, and how infantile the world it is making has become.

Read Part 1 and Part 2.

Wayne Cristaudo is a philosopher, author, and educator, who has published over a dozen books. He also doubles up as a singer songwriter. His latest album can be found here.

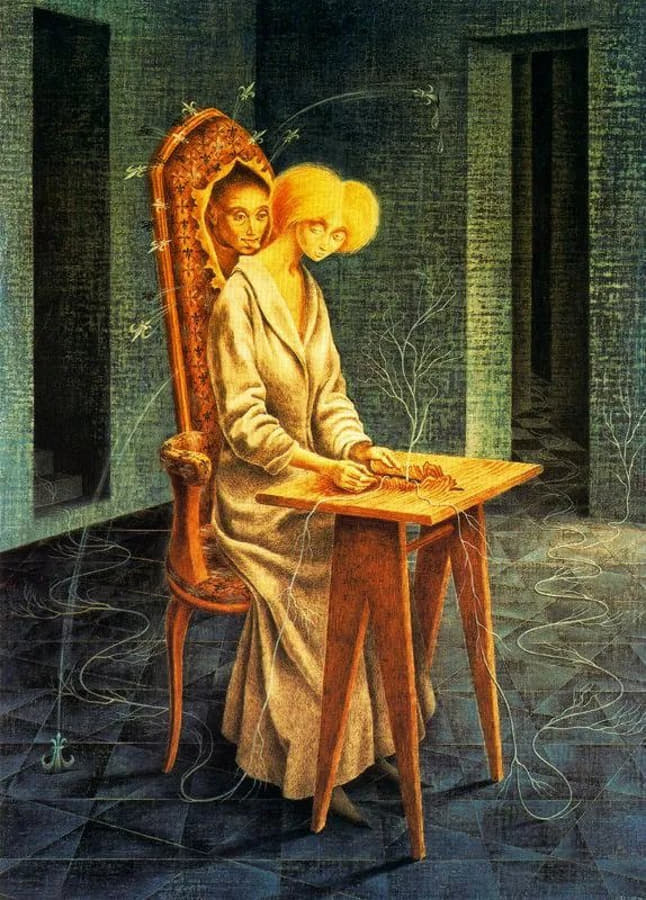

Featured: Presencia Inquietante (Unseetling Presence), by Remedios Varo; painted in 1959.