The article that follows served as an important basis for Dennis Bonnette’s book, Origin of the Human Species (3rd ed., 2014). The book explores questions raised by evolutionary theory—ultimately focusing on what we may confidently say about human origins, and showing that belief in Adam and Eve as the human race’s first parents remains reasonable, despite many modern evolutionists’ skepticism.

This article also serves the book’s overall aims by defending the uniqueness of man and of his essential superiority over lower animals, including other primates. This is an updatred version of the original article. Dr. Bonnette previously wrote about alien life-forms.

Preamble

As we approach the end of the first quarter of the twenty-first century, we find sudden interest in claims about possible space aliens – with people wondering, if they exist at all, what kind of creatures these might be. At the same time, we have now developed computers with artificial intelligence (AI), which some claim to be sentient, thinking entities, that might even constitute a new form of living person! These kinds of questions are all the more vexing today, given biological evolution’s tendency to view man as merely a highly developed animal. Some distinguish man by believing he uniquely has a soul. But the ancients always maintained that a soul was simply a principle of life, so that every living thing has a soul. This is evinced by the very fact that we name animals from the Latin, “anima,” which means “life principle” or “soul.” Religious believers quickly distinguish that man alone has a spiritual soul, but are then immediately challenged by evolutionists who maintain that man differs in complexity, but not in kind, from lower animals.

Understandably, this same confusion reigns about the nature of possible space aliens and AI computers. If we cannot even clearly distinguish true humans from other animals, how do we expect to understand the nature of creatures from outer space or computers so advanced that they can seemingly mimic every human ability, plus much more? For these reasons alone, it is useful to study the topic of this article, which is a scientific and philosophical examination of the “frontier” claims about lower primates to the effect that they can achieve what was once thought to be the unique possession of human beings, namely, genuine language.

This article will show clearly the difference between lower animals’ sensitive cognitive abilities and human beings’ radically superior intellectual cognitive powers. These powers manifest the deeper ontological distinction between animal and human natures. Once the radical distinction between human and animal natures is clearly grasped, the nature of those possible space alien “cousins” as well as the essential differences, if any, between man and AI computers can be better understood.

The naturalistic mentality of many animal psychologists anticipates that subhuman primates will tend to approach human beings’ mental powers, manifested in part through alleged ape linguistic abilities. Thus, the latter part of the twentieth century witnessed many ape-language studies, complete with claims that chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and certain other subhuman primates, have been taught to use various forms of sign language and can now understand the meanings of hundreds of words, form sentences, and communicate effectively with humans and even among themselves. These claims feed the inevitable conclusion that man himself no longer holds a preeminent place in the animal kingdom, that his is but one among many other species, and that continued belief that God made him in His image and gave him dominion over all lower creatures is simply an outdated religious myth.

I examine subhuman linguistic claims in two steps: First, I show that even some evolutionist natural scientists, who have analyzed ape-language studies, conclude that apes have not yet mastered true language. In 1979, some researchers challenged ape-language claims by arguing that such behavior can be explained by non-linguistic mechanisms, such as (1) simple imitation, (2) the Clever Hans effect, (3) the anthropomorphic fallacy, and (4) rapid non-syntactical signing to obtain immediate sensible rewards. Two of the most important claims—(1) that apes could combine signs creatively in novel sequences and (2) that they showed knowledge of syntactic structure—appear to be based merely upon anecdotal data, not upon acceptable scientific methodology.

Second, I use philosophical analysis to demonstrate (1) why human intellectual knowledge is needed to possess genuine language, and (2) why it will be forever impossible for subhuman primates to exhibit true linguistic ability. Materialist explanations of animal and human behavior miss the crucial distinction between sense and intellect. Animals possess sense knowledge alone, whereas man possesses both sense and intellectual knowledge. Intellectual knowledge is the hallmark of the human spiritual soul, and is not shared with our animal friends.

Man exhibits intellectual knowledge by (1) forming abstract concepts, (2) making judgments, and (3) reasoning from premises to conclusions in logical fashion. Subhuman animals’ sensory abilities, including imagination and sense memory, enable them to manipulate sensory data and use inborn natural signs to communicate instinctively, and even to be taught by man to use humanly-invented signs. Still, they do not understand the meanings their signs express, nor form judgments, much less engage in reasoning. The hallmark of all ape behavior, including trained language use, is its relentless focus on immediate sensory rewards, such as food, toys, sex, or interaction with other animals. Abstract goals, such as earning a diploma or getting a better job or serving God, mean nothing to apes and will not beget sign language responses.

Proof of my claims here requires (1) showing that ape-language research data can be explained in terms of mere sense knowledge, and (2) showing that such behavior must be so explained by positive proof that apes lack intellect. The first task is achieved largely in terms of the abovementioned scientific criticisms and also by pointing out that computers, which actually understand nothing and are not even alive, can imitate human linguistic behavior simply by manipulating data. Apes, with relatively large brains and elaborate sense faculties, can also accomplish such impressive feats, but this need not mean that they possess true linguistic comprehension any more than computers do.

The second task, to show that subhuman primates’ linguistic behavior must be read as mere sensory activity, requires positive demonstration that apes lack true intellect. Four formal effects demonstrate true intellect: (1) genuine speech, (2) true progress, (3) knowledge of relations, and (4) knowledge of immaterial objects. In their wild state, with no human influence, animals, including apes, (1) fail to develop true language, and (2) fail to make genuine progress. Even in a domesticated environment, they still (3) show no understanding of real relationships (such as cause and effect)—merely learning to associate images, and (4) clearly fail to develop the sciences and religious beliefs typical of human abstract understanding. While details of this proof require reading the article itself, the conclusion is that subhuman primates and other animals fail all four tests of true intellectual activity. Hence, man alone possesses true intellect.

The radical difference between mere animals and true human beings is manifested acutely by the insurmountable distinction between the sense image and intellectual concept. The image is always particular, concrete, imaginable, and has sense qualities, such as when we form the image of an individual human being or a particular triangle. But, the concept is always universal, abstract, unimaginable, and lacks all sense qualities, as when we understand the meaning of terms, such as “humanity” or “triangularity.” Human beings have both kinds of knowing, whereas brute animals are restricted to knowledge of images alone. Again, full details are in the article.

We grasp fully the radical limitations of brute sense knowledge only when we compare it to man’s rich, expansive intellectual life which enables him to study all the sciences, to create exponential technological progress, to embrace transcendental religious belief systems, and even to reflect upon his own human nature so as to grasp its spiritual dimensions—destined to eternal life, and to the knowledge of and union with God Himself. These insights demonstrate that evolutionist claims about ape-language studies pose no threat whatever to human essential superiority. Man still has his God-given dominion over beasts—and always will.

Once we fully understand the radical distinction between lower animals and true human beings, we will then easily determine the essential nature of any possible space aliens.

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to enquire whether, in the face of evidence gained from recent ape-language studies, it is still possible to delineate clearly between human intellectual life and brute sentient life—to refute the claims of the sensist philosophers who would reduce all human knowledge and activities to the level of mere sensation and sense appetite. This question cannot, and need not, be answered exhaustively in this relatively short study of the matter. In order to respond in the affirmative, it will suffice that we be able to show that even the most sophisticated sensory activities of animals bear no legitimate threat to the radical superiority of the human intellect—an intellect whose spiritual character is rationally demonstrable.

Nor is it our intent to present here in detail the formal proofs for the spiritual nature of the human soul which have been offered by St. Thomas Aquinas. (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 75, aa. 1-7). Rather, our primary focus will be upon an examination of evidence and arguments which reveal the inability of lower animals to present a credible challenge to the uniqueness of human intellectual life.

It has long been observed in nature that certain lower forms of life often imitate the activities and perfections of higher forms. For example, the tropisms found in certain plants—while not actually constituting sensation—nonetheless deceptively simulate the sensitive reactions proper to animals alone. So too, the human-like behaviour of many “clever” animals has caused much contemporary confusion on the part of, not only the general populace, but also even presumed experts on animal behaviour.

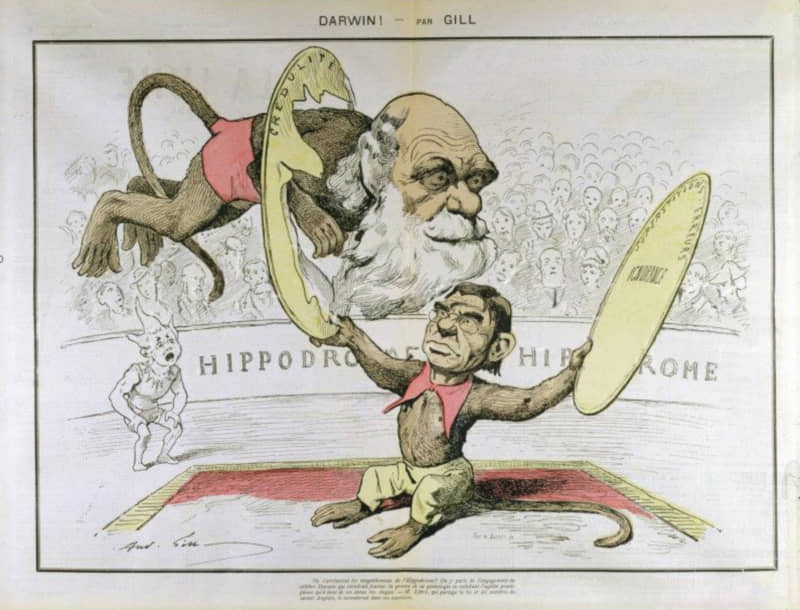

In great part this confusion has arisen because of the success of Darwinian evolution and its attendant reductionism in dominating for much of this century the academe of those natural sciences which deal with animal and human behaviour. Thus psychologists, zoologists, biologists, anthropologists, and so forth, tend to view human behaviour as nothing but an extension in degree, not in kind, of lower animal behaviour. Nowhere is this tendency more acutely seen than in the controversies arising out of contemporary ape-language studies.

Beginning nearly a century ago, various attempts have been made in a small number of research projects to teach chimpanzees and other primates to talk. The most successful techniques have involved the use of American Sign Language and computer-based artificial language systems. Great publicity has attended these efforts since the 1970s with claims of hundreds of words being “understood” by these subjects, new complex words being invented, and even sentences being formed with two-way “conversations” taking place, not only between trainer and primate, but even between primate and primate!

Dissent and Defense

Yet, by 1979, a simmering academic controversy about the legitimacy of primate linguistic credentials burst into view of the general public with the publication of two critical articles in Psychology Today (November 1979, Vol. 13, No. 6.) —one by Columbia University psychologist H. S. Terrace, the other by University of Indiana anthropologists Thomas and Jean Sebeok. Through a very careful re-evaluation of the signing activities of the subject of his own research project, a chimpanzee named Nim Chimpsky, Terrace concluded, “I could find no evidence of an ape’s grammatical competence, either in my data or those of others” (Psychology Today, 67).

The Sebeoks, moreover, argued that animal researchers have been engaging in a good deal of unwitting self-deception in accepting as linguistic competence behaviour which is actually the result of unconscious cuing. What they refer to is what is widely called the Clever Hans effect—named after a famous turn-of-the-century “thinking” horse whose “intelligent” answers to questions were exposed by Berlin psychologist Oskar Pfungst as simply the result of unintentional cues being given by his questioners.

The defenders of apes’ linguistic abilities engaged in immediate counter-attack—producing an intellectual battle which rages to the present day. It is important for us to note that almost all the participants in this debate to date [1993] are natural scientists who are of one mind concerning man’s materialistic and evolutionary origins. The input of dualist philosophers and theologians has been [as of 1993] virtually nil. Thus the critics of the “linguistic” apes, it should be observed, operate largely from a perspective which views man as nothing but a highly developed animal and which prescinds utterly from any philosophical arguments for the existence and spiritual nature of the human soul.

Among the ape’s defenders, we find Suzanne Chevalier-Skolnikoff who points out that the famed signing chimp, Washoe, has taught another chimp, Loulis, how to sign—although she concedes, “Loulis learned his signs mainly by imitation” (The Clever Hans Phenomenon: Communication with Horses, Whales, Apes, and People, 1981, 89-90.)

Chevalier-Skolnikoff also presents the following remarkable claims about ape behaviour:

“Deception, “lying,” and joking are all behaviours that logically are dependent upon mental combinations, or symbolization, and, like other stage 6 behaviours, they cannot be cued. As mentioned above, deception, lying, and joking all appear in stage 6 in nonsigning apes, and I have observed this kind of behaviour both nonlinguistically and in conjunction with signing in the gorilla Koko during this stage. Consequently, I have no reason to doubt, as some authors have, Patterson’s reports that Koko tells lies and jokes.

“Besides lying and joking, the gorilla Koko also has been recorded to argue with and correct others. Arguing and correcting are dependent upon comparing two viewpoints of a situation—existing conditions with nonexisting ones—and therefore require mental representation” (Clever Hans, 83).

Intentional lying, deception, joking, arguing, and correcting—if actually demonstrable from the research data—would, of course, bespeak unequivocally the presence of intellectual activity on the part of apes. Yet, this is precisely why we must be so very careful about drawing such inferences from the available evidence. We must always be cautious not to assign facilely to higher causes that which could readily be explained in terms of lower causes.

The Anthropomorphic Fallacy

While this is scarcely a proper context in which to explore and critique the multiple data upon which Chevalier-Skolnikoff’s judgments are formed, it must be noted that such judgments necessarily flow from an interpretation of the concrete details examined. And herein lies the greatest danger to the human researcher who attempts to “read” the animal subject. The Sebeoks put the matter thus:

“Investigators and experimenters, in turn, accommodate themselves to the expectations of their animal subjects, unwittingly entering into a subtle nonverbal communication with them while convincing themselves, on the basis of their own human rules of interpretation, that the apes’ reactions are more humanlike than direct evidence warrants” (Psychology Today, November 1979, 91).

In a word, what the Sebeoks describe is the infamous anthropomorphic fallacy, that is, the error of attributing human qualities to animals based upon our nearly irresistible temptation to put ourselves in the brute’s place, and then, to view his actions in terms of our own human intellectual perspectives. The universality of this human tendency is such that even experts in animal behaviour frequently fail to avoid its pitfalls.

The specific content of such habitual anthropomorphism by ape researchers is thus described by the Sebeoks:

“Time and again researchers read anomalous chimpanzee and gorilla signs as jokes, insults, metaphors, and the like. In one case, an animal was reported to be deliberately joking when, in response to persistent attempts to get it to sign “drink” (by tilting its hand at its mouth), it made the sign perfectly, but at its ear rather than its mouth” (Psychology Today, 81).

Clearly, this sort of suspicion strikes at the heart of Koko’s claimed performance of “deception, lying, joking, etc.”

In fact, the synergism of anthropomorphism and the Clever Hans effect is seen by psychologist Stephen Walker as justifying inherent skepticism about any and all claims made on behalf of American Sign Language trained apes.

“The most important type of unwitting human direction of behaviour which has been interpreted as the product of the mental organisation of the apes themselves is in the “prompting” of sequences of gestures in animals trained with the American Sign Language method…. As practically all instances of sequences or combinations of gestures by chimpanzees or gorillas are made in the context of interactions with a human companion, there is virtually no evidence of this kind which is not vulnerable to the charge that the human contact determined the sequence of combinations observed” (Animal Thought, 1983, 373-374).

Yet, not all ape communication techniques employed by researchers have involved the use of American Sign Language. Plastic symbols, computer-controlled keyboards, and other artificial devices have been utilized in order to lessen, or possibly eliminate, human influence on the process.

In defending the research of Savage-Rumbaugh—who used a computer-controlled keyboard system—psychologist Duane M. Rumbaugh insists that the evidence shows the clear capacity for categorization free from any Clever Hans effect:

“For our apes the symbols are referential, representational, and communicative in value. Data obtained and reported by Savage- Rumbaugh at that convention made it clear that the chimpanzees Sherman and Austin categorize learned symbols as foods and tools (nonedibles) just as they categorize the physical referents themselves. These data were obtained from tightly controlled test situations in which the animals had no human present in the room at the keyboard to influence their choice of keys for purposes of categorizing” (Clever Hans, 33. See also ibid., 26-59).

In this, though, as in all other instances of supposed lower primate “intentional” communication, the fundamental problem which remains is the influence of man in “programming” the training and responses of the animals, and then, man’s tendency to anthropomorphize the interpretation of the results of this very influence. The results never seem quite as definitive to the sceptics as they do to the researchers who nearly live with the subjects they wish to “objectively” investigate. The inherent difficulty posed for those who would completely eliminate the Clever Hans effect is well-stated by the Sebeoks.

“Apes simply do not take part in such man-made laboratory tests without a great deal of coaxing. The world’s leading authority on human-animal communication, Heini Hediger, former director of the Zurich zoo, in fact deems the task of eliminating the Clever Hans effect analogous to squaring the circle—‘if only for the reason that every experimental method is necessarily a human method and must thus, per se, constitute a human influence on the animal’” (Psychology Today, 91).

Thus, we see that the Sebeoks support Hediger’s claim that total elimination of the Clever Hans effect would constitute an actual contradiction in terms—a goal entirely impossible of attainment.

Escaping Clever Hans

And yet, it is important not to rest the entire case against “talking” apes upon the Clever Hans effect as championed by the Sebeoks. Walker points to research done by Roger Fouts, the Gardners (with the famous Washoe), and Savage-Rumbaugh as appearing to escape the charge of unintentional cuing. Concerning the latter, he writes:

“When two chimpanzees exchanged information between themselves, using the computer-controlled keyboard system, with experimenters not in the same room (Savage-Rumbaugh et al., 1978b), the evidence seems relatively robust” (Animal Thought, 373).

It would appear that the phrase, “Clever Hans effect,” is now being given a meaning which includes two distinct aspects: (1) unintentional cuing of the animals and (2) any human influence upon the animals. While the Sebeoks and other critics are undoubtedly correct in insisting that human influence is inherent in every ape experiment devised by man, yet it is also clearly not the case that unintentional cuing can explain all significant ape communicative achievements.

Given exhaustive, and sometimes exhausting, training by researchers, several novel and rather impressive ape communication performances—free of all unintentional cuing—have been reasonably well documented. What is referred to here is not merely the well-known abilities of trained chimpanzees and gorillas to associate arbitrary signs with objects, nor even their ability to string together series of such signs in what Terrace and others dismiss as simply urgent attempts to obtain some immediately sensible reward.

Rather, more impressive experimental results are now forthcoming, for example, the Savage-Rumbaugh experiments in which two chimpanzees were taught to communicate and cooperate with each other—using a computer keyboard to transmit information revealing the location of hidden food (Animal Thought, 365-367).

In another experiment, after extensive training and prompting, the same animals learned to cooperate with one another by handing over the correct tool needed to obtain food when their primate partner requested it—again by use of computer symbols and without human presence during the actual experiment. Walker offers his inferences therefrom:

“There can be little doubt, in the case of this experiment, that the visual patterns used in the keyboard system had mental associations with objects, and that the chimpanzee who punched a particular key did this in the expectation that the other animal would hand him a particular tool” (Animal Thought, 369).

Still later, these same prodigious chimpanzees advanced to seemingly quite abstract symbolic associations:

“When they were trained with arbitrary symbols assigned to the two object categories “foods” and “tools” Austin and Sherman successfully selected the appropriate category, when shown arbitrary symbols which were the names for particular foods or tools (Savage-Rumbaugh et al., 1980). That is, they were able to label labels, rather than merely label objects: for instance if shown the arbitrary pattern indicating “banana” they responded by pressing the key meaning “food,” but if shown the symbol for “wrench” they pressed the “tool” key” (Animal Thought, 369-370).

Finally, Woodruff and Premack are reported to have devised a cuing-free experiment in which chimpanzees indicated by gesture the presence of food in a container to human participants who did not know its location. They would correctly direct “friendly” humans who would then share the food with them, but would mislead “unfriendly” humans who would not share the food—since the animals were then permitted to get the food for themselves (Animal Thought, 370-371).

Each of the above experimental “successes” is of interest since each appears to be quite free, not from original human influence in the training process, but at least from the Clever Hans effect of unintentional cuing.

Moreover, they demonstrate fairly complex symbol-object associative skills, “intentional” communication, and even, in the last case, some form of “deception.” We place quotation marks about the terms, “intentional” and “deception,” because the exact cognitive content of such acts remains to be properly understood.

Yet, despite the above-described notable results of non-cued experiments as well as claims of hundreds of “words” being learned and of “sentences” and even “dialogue” being articulated by signing apes, careful natural scientific observers remain convinced of essential differences still remaining between ape and human capabilities.

The Uniqueness of Human Speech

After extremely careful analysis of all the relevant data and arguments presented by the ape-language studies, Walker finally concludes that man’s linguistic capabilities remain unique:

“Apes trained to employ artificial systems of symbolic communication ought not, therefore, to be said to have acquired a language, in the sense that people acquire a language. Human language is unique to humans, and although some of the distinctive features of human speech, such as the mimicking of sounds, may be observed in other species, the resemblance between, for instance, the trained gesturing of a chimpanzee and communication via sign- language among the human deaf is in some senses no greater than the resemblance between the speech of a parrot and that of its owner” (Animal Thought, 377-378).

A parrot might, hypothetically, be trained to say, “Polly wants a cracker because Polly is hungry and because Polly knows that a cracker would neutralize the hyperacidity of his stomach acid and thereby reestablish its normal pH.” It might even be trained to say this in order to obtain food when hungry. Yet, no one would seriously contend that the bird in question actually understands concepts such as “neutralize,” “hyperacidity,” and “normal pH.” It is one thing to associate a trained response with a given stimulus, but quite another to grasp intellectually the intrinsic nature of each in all its various elements as well as the nature of the cause-effect relationship entailed.

Walker also concludes that—aside from their evident superiority in terms of the “sheer quantity” of associations learned—the apes’ capabilities do not qualitatively exceed those of lower species, for example, as when a dog responds to the arbitrary sign of a buzzer in order to obtain a piece of meat through the performance of some trained action:

“In so far as it can be demonstrated that the apes establish a collection of associations between signs and objects, then the results of their training extend further than any previously observed form of animal learning, but it is not clear that they need a substantially different kind of ability to make these associations from that which may be used by other mammals to respond to smaller sets of signals” (Animal Thought, 378).

He also notes the essential dependence of the animals upon human influence in order to assure their performance:

“Even when a computer-controlled keyboard is used, so that tests can be made in the absence of a human presence, social interactions between human trainers and the animal being trained are apparently necessary if the animal is to show any interest in using the keyboard (Rumbaugh, 1977)” (Animal Thought, 379).

Finally, Walker eloquently describes the radical wall of separation which distinguishes man from all the lower primates—pointing in particular to man’s unique possession of language in its proper meaning:

“Of all the discontinuities between man and animals that could be quoted, including the exclusively human faculties for abstraction, reason, morality, culture and technology, and the division of labour… the evergreen candidate for the fundamental discontinuity, which might qualify all others, is language… In a state of nature we expect humans to talk, and by comparison, the most unrelenting efforts to induce our closest living relatives to reveal hidden linguistic potential have left the discontinuity of speech bloodied, but unbowed” (Animal Thought, 387).

With respect to the linguistic facility of apes in comparison to man, Walker maintains that chimpanzees form “mental” associations—but that their abilities pale against those displayed by people:

“It seems necessary to accept that under the conditions described, chimpanzees form mental associations between perceptual schemata for manual gestures and others for object categories. This is not to say, in Romanes’s phrase, that they can mean propositions, in forms such as “all chimpanzees like bananas….” [S]ince it has not been convincingly demonstrated that one chimpanzee gesture modifies another, or that there is any approximation to syntax and grammar in the comprehension or expression of artificial gestures, the similarity between the use of individual signs by apes, and the use of words by people, is definitely limited” (Animal Thought, 357).

Despite Walker’s willingness here to defend the uniqueness of man, we note that he yet shares the tendency of most natural scientists to describe lower primates’ associative imaginative acts while employing philosophically misapplied terms such as “mental,” “understand,” and “think.” In proper philosophical usage, such terms are strictly predicable of human intellectual activities. Their application to brute animals in this context serves only to confuse the intellectual with the sentient order.

In an observation which strikes at the very heart of all ape language experiments, Hediger supports the claim by biophilosopher Bernard Rensch, who noted in 1973 that nothing like human language has ever been found among any of the apes in the state of nature. Hediger comments:

“In other words, with all animals with which we try to enter into conversation we do not deal with primary animals but with anthropogenous animals, so-to-speak with artifacts, and we do not know how much of their behaviour may still be labelled as animal behaviour and how much, through the catalytic effect of man, has been manipulated into the animal. This is just what we would like to know. Within this lies the alpha and omega of practically all such animal experiments since Clever Hans” (Clever Hans, 5).

This amounts to a recognition that all ape-language studies presuppose the invention of true language by man. This peculiarly human invention is then imposed by man upon the apes. The day on which apes create their own linguistic system is still the dream of science fiction.

As is well known to the philosophical science of psychology, human language consists of a deliberately invented system of arbitrary or conventional signs. (Aristotle, On Interpretation, 1 (16a3-8).) Thus the English word “red” could just as well have stood for the natural colour green—except for the convention or agreement by all that it should represent just what it does. The alternative to such arbitrary signs consists of what are termed natural signs, which, as the name implies, flow from the very nature of something. Thus smoke is a natural sign of fire, a beaver slapping its tail on water is a natural sign of danger, and the various calls of birds are signs of specific natural meanings—which cannot be arbitrarily interchanged or invented. The hiss of a cat is never equivalent to its purr.

From all this, it is clear that in teaching apes to “talk” man is simply imposing upon them his own system of arbitrary or conventional signs. The signs belong to man, not to the apes. The apes use them only because we train them to do so. We thus turn the apes, as Hediger says, into “artifacts” of our own creation.

Hediger emphasizes the importance of not underestimating the impact of human training upon lower species:

“This amazing act of training causes one to ponder the manifold efforts of several researchers to enter into language contact, into a dialogue with apes…

“In each case the chimpanzees were demonstrated the desired actions with the hope that they would react in a certain way… with Washoe, Sarah, Lana, and so forth, it is the production of certain signs in which we would like to see a language. But how can we prove that such answers are to be understood as elements of a language, and that they are not only reactions to certain orders and expression, in other words simply performances of training?” (Clever Hans, 9).

One perhaps should ponder here that it is not brute animals alone which can react to training in a way which bespeaks performance but lack of understanding. Have we not all, at one time or another, heard a small child speak a sentence—even with perfect syntax and grammar—whose meaning obviously utterly eludes him? Or, at least, we hope it eludes him! And, if such can occur in children through training and imitation, one can well understand Hediger’s hesitancy to attribute intellectual understanding to a brute animal when such acts could well be explained by simple performance training.

Moreover, Hediger makes a suggestion which reveals the extreme difficulty entailed in assuring that apes actually do understand the meanings of the “words” they gesture under present methods:

“I do not doubt that Washoe and other chimps have learned a number of signs in the sense of ASL. But it seems to me that a better clarification could be reached mainly through the introduction of the orders “repeat” and “hold it.” By this the chimpanzee could show that he really understands the single elements and does not execute fast, sweeping movements into which one possibly could read such elements” (Clever Hans, 9).

Since such “stop action” techniques have never even been attempted in present ASL trained apes, it would seem that demonstration of true intellectual understanding of hand signs in them is virtually impossible. By contrast, humans frequently do explicate their precise meanings to each other—even to the point of writing scholarly papers immersed in linguistic analysis.

The Inferiority of Apes

In contrast with the rather elevated dialogue about apes’ supposed “mental” abilities, Hediger makes a fundamental observation designed to cut the Gordian knot of much of the controversy. Analogous to the old retort, “If you are so smart, why aren’t you rich?,” Hediger’s rather fatally apropos version runs essentially thus: “If apes are so intelligent, why can’t they learn to clean their own cages?”

“If apes really dispose of the great intelligence and the highly developed communication ability that one has attributed to them lately—why in no case in the zoos of the world, where thousands of apes live and reproduce, has it been possible to get one to clean his own cage and to prepare his own food?” (Clever Hans, 13).

In a follow-up comment made, presumably, without any personal prejudice against apes, Hediger writes, “Apes have no notion of work. We might perhaps teach an ape a sign for work but he will never grasp the human conception of work” (Clever Hans, 13).

Finally, Hediger notes that “the animal has no access to the future. It lives entirely in the present time” (Clever Hans, 14). And again, Hediger insists, “To my knowledge, up to now, no animal, not even an ape, has ever been able to talk about a past or a future event” (Clever Hans, 16).

If argument from authority has any force at all, it should be noted here that Heini Hediger is described by the Sebeoks as the “world’s leading authority on human-animal communication… (and) …former director of the Zurich zoo” (Psychology Today, 91).

Moreover, the conclusions by Walker cited above warrant special attention because his book, Animal Thought, represents an outstanding synthesis of available data on animal “mental” processes and includes an extensive review of the recently conducted ape-language studies (Animal Thought, 352-381).

In addition to the specific distinctions between ape and man noted above, the philosopher notices a pattern of evidence which tends to confirm his own conclusions. For it is clear that the apes studied are, in all well-documented activities, exclusively focused upon the immediate, particular objects of their sense consciousness. They seek concrete sensible rewards readily available in the present. Such documented observations are entirely consistent with the purely sentient character of the matter-dependent mode of existence specific to animals.

Apes have no proper concept of time in terms of knowing the past as past or the future as future. Nor do they offer simply descriptive comment or pose questions about the contents of the passing world—not even as a small child does when he asks his father why he shaves or tells his mother she is a good cook even though his stomach is now full.

Time and again it is evident that the most pressing obsession of any ape is the immediate acquisition of a banana (or its equivalent). It has little concern for the sorts of speculative inquiry about that same object which would concern a botanist.

In fact, the whole experiential world of apes is so limited that researchers are severely restricted in terms of their selection of motivational tools capable of use in engaging them to perform or dialogue. Hediger laments:

“Therefore there remain the essential daily needs, above all metabolism, food and drink, social and sexual contact, rest and activity, play and comfort, conditions of environment in connection with the sensations of pleasure and dislike, some objects, and possibly a few more things. This is indeed rather modest” (Clever Hans, 14).

Aristotle makes much the same point:

“The life of animals, then, may be divided into two acts—procreation and feeding; for on these two acts all their interests and life concentrate. Their food depends chiefly on the substance of which they are severally constituted; for the source of their growth in all cases will be this substance. And whatsoever is in conformity with nature is pleasant, and all animals pursue pleasure in keeping with their nature” (History of Animals, VIII, 1, [589a3-589a9]).

Small wonder the apes will neither philosophize nor clean their cages!

We have seen above that much of ape-communicative skills can be explained in terms of simple imitation or unintentional cuing. Even in the carefully controlled experiments designed to lessen or eliminate all cuing, the factor of human influence in the extensive training needed to get apes to initiate and continue their performance simply cannot be eliminated.

Yet, there seems to remain a legitimate need for further explanation of the impressive ape-communicative skills manifested as the product of the experiments done by Savage-Rumbaugh and others. Granted, exhaustive training may explain why these chimpanzees and gorillas act in fashions never seen in the state of nature. Yet, this does not fully avoid the need to explain the remarkable character of the behaviour produced by this admittedly artificial state into which the animals have been thrust by human imposition.

In the first place, it must be noted that there is no undisputed evidence of ape-language skills which exceed the domain of the association of sensible images. Even the categorization of things like tools and actions does not exceed the sensible abilities of lower species, for example, the ability of a bird to recognize selectively the objects which are suitable for nest building. Nor does even the ability to “label labels” exceed, in principle, the province of the association of internal images.

Intellectual Activity

It should be observed here that the nature of intellectual knowledge does not consist merely in the ability to recognize common sensible characteristics or sensible phenomena which are associated with a given type of object or action. Such sentient recognition is evident in all species of animals whenever they respond in consistent fashion to like stimuli, as we see in the case of the wolf sensing any and all sheep as the object of his appetite.

On the contrary, the intellect penetrates beyond the sensible appearances of things to their essential nature. Even at the level of its first act (that is, simple apprehension or abstraction), the intellect “reads within” the sensible qualities of an entity—thereby grasping intelligible aspects which it raises to the level of the universal concept. Thus, while we can imagine the sensible qualities of an individual triangle, we cannot imagine the universal essence of triangularity—since a three-sided plane figure can be expressed in infinitely varied shapes and sizes. Yet, the concept of triangularity is a proper object of intellectual understanding. Thus, the essence of conceiving the universal consists, not merely in an association of similar sensible forms, but in the formation of a concept abstracted from the individuating, singularizing influence of matter and freed from all the sensible qualities which can exist only in an individual, concrete object or action.

So too, the correct identification of, communication about, and employment of an appropriate tool by a chimpanzee (in order to obtain food) is no assurance of true intellectual understanding. Indeed, a spider which weaves its web to catch insects is repeatedly creating the same type of tool designed exquisitely to catch the same type of victim. Yet, does anyone believe that this instinctive behaviour bespeaks true intellectual understanding of the means-end relation on the part of the spider? Hardly! The evident lack of intelligence in the spider is manifest the moment it is asked to perform any feat or task outside its fixed instinctive patterns.

Whether “programmed” by instinct, as in the case of the spider, or by man, as in the case of the chimpanzee, each animal is simply playing out its proper role in accord with pre-programmed habits based upon recognition or association of sensibly similar conditions. Certainly, no ape or any other brute animal understands the means as means, the end as end, and the relation of means to end as such. The sense is ordered to the particular; only intellect understands the universal.

One may ask, “How do we know that the ape does not understand the intrinsic nature of the objects or ”labels“ he has been trained to manipulate?” The answer is that, just like the spider which cannot perform outside its “programmed” instincts, so too, the ape—while appearing to act quite “intelligently” within the ambit of its meticulous training, yet exhibits neither the originality nor creative progress which man manifests when he invents at will his own languages and builds great civilizations and, yes, keeps his own “cages” clean!

Therefore, while it is clear that certain apes have been trained to associate impressive numbers of signs with objects, it is also clear that the mere association of images with signs and objects, or even of images with other images, does not constitute evidence of intellectual understanding of the intrinsic nature of anything. And it is precisely such acts of understanding which remain the exclusive domain of the human species.

Yet, the field of contest of ape-language studies is centred not only upon the first act of the intellect discussed above, but also upon the second and third acts of the intellect, that is, upon judgment and reasoning. Thus Chevalier-Skolnikoff insists that the chimpanzee, Washoe, and the gorilla, Koko, exhibit true grammatical competence as, for example:

“breakfast eat some cookie eat,” signed by Koko at 5 years 6 months and “please tickle more, come Roger tickle,” “you me go peek-a-boo,” and “you me go out hurry,” signed by Washoe at about 3 years 9 months. Besides providing new information, the structures of these phrases (like those of the novel compound names) imply that they are intentionally planned sequences” (Clever Hans, 83).

It is in the expression of such “intentionally planned sequences” that Koko is reported to have argued with and corrected others; for example, when Koko pointed to squash on a plate and her teacher signed “potato,” Koko is reported to have signed “Wrong, squash” (Clever Hans, 84).

Even if one is disposed to accept the intrinsically anecdotal character of all such data, we must remember the inherent danger of anthropomorphic inferences warned against by Walker, the Sebeoks, and others. As Walker concludes, because of the necessary interaction with a human companion during such communication, “there is virtually no evidence of this kind which is not vulnerable to the charge that the human contact determined the sequence of combinations observed” (Animal Thought, 374).

And while it is not evident precisely how the animal was trained to sign “wrong” or otherwise indicate a negative, such a sign when associated with a correct response (for example, “squash”) need not reflect a genuinely intellectual judgment. The correct response itself is simply proper categorization which is the product of training. Its association with a negative word-sign like “wrong” or “no” may simply be a sign which is trained to be elicited whenever the interlocutor’s words or signs do not fit the situation. The presumption of intellectual reflection and negative judgments in such cases constitute rank anthropomorphism in the absence of other specifically human characteristics, for example, there appears to be no data whatever recording a “correction” or “argument” entailing a progressive process of reasoning. Rather, two signs, such as “No, gorilla” or “Wrong, squash” constitute the entire “argument.” Compare such simple “denials” to the lengthy syllogistic arguments—often of many steps—offered in human debate. The apes, at best, appear to offer us merely small collections of associated simple signs—usually united only by the desire to attain an immediate sensible reward.

As noted earlier, apes have been reported to sign to other apes (Clever Hans, 89-90). They have even been reported to sign to themselves when alone (Clever Hans, 86). Such behaviour, though striking, simply reflects the force of habit. Once the proper associations of images to hand signs have been well established, the tendency to respond in similar fashion in similar contexts—whether in the presence of man or another ape or even in solitude—is hardly remarkable.

Critiquing the Research Data

Perhaps the most stinging defection from the ranks of those advocating an ape’s grammatical competence is that of H. S. Terrace. His own research project, whose subject was a chimpanzee named Nim Chimpsky, eventually led him to question the legitimacy of initially favourable results. He then began a complete re-evaluation of his own prior data as well as that which was available from other such projects. Terrace now insists that careful analysis of all ape-language studies fails to demonstrate that apes possess grammatical competence.

Terrace suggests that in two studies using artificial language devices what the chimpanzees “learned was to produce rote sequences of the type ABCX, where A, B, and C are nonsense symbols and X is a meaningful element” (Clever Hans, 95). Thus, he argues, while the sign “apple” might have meaning for the chimpanzee, Lana,

“…it is doubtful that, in producing the sequence please machine give apple, Lana understood the meanings of please machine and give, let alone the relationships between these symbols that would apply in actual sentences” (Clever Hans, 95).

Terrace points to the importance of sign order in demonstrating simple constructions, such as subject-verb-object, and then criticizes the Gardners for failing to publish any data on sign order regarding Washoe (Clever Hans, 96).

Perhaps the single most important contribution of Terrace has been his effort “to collect and to analyse a large corpus of a chimpanzee’s sign combinations for regularities of sign order” (Clever Hans, 97). Moreover, he initiated:

“… a painstaking analysis of videotapes of Nim’s and his teacher’s signing. These tapes revealed much about the nature of Nim’s signing that could not be seen with the naked eye. Indeed they were so rich in information that it took as much as one hour to transcribe a single minute of tape” (Clever Hans, 103).

These careful examinations of Nim’s signing activities led Terrace to conclude:

“An ape signs mainly in response to his teachers’ urgings, in order to obtain certain objects or activities. Combinations of signs are not used creatively to generate particular meanings. Instead, they are used for emphasis or in response to the teacher’s unwitting demands that the ape produce as many contextually relevant signs as possible” (Clever Hans, 107-108).

Terrace points out the difficulty involved in attempting to evaluate the performance of the other signing apes:

“… because discourse analyses of other signing apes have yet to be published. Also, as mentioned earlier, published accounts of an ape’s combinations of signs have centred around anecdotes and not around exhaustive listings of all combinations” (Clever Hans, 108).

Seidenberg and Petitto raise similar objections to the anecdotal foundation for some of the most significant claims made on behalf of apes:

“A small number of anecdotes are repeatedly cited in discussions of the apes’ linguistic skills. However, they support numerous interpretations, only the very strongest of which is the one the ape researchers prefer, i.e., that the ape was signing “creatively.” These anecdotes are so vague that they cannot carry the weight of evidence which they have been assigned. Nonetheless, two important claims—that the apes could combine signs creatively into novel sequences, and that their utterances showed evidence of syntactic structure—are based exclusively upon anecdote” (Clever Hans, 116).

Terrace also states that he has carefully examined films and videotape transcripts of other apes, specifically Washoe and Koko. Regarding the former, he concludes, “In short, discourse analysis makes Washoe’s linguistic achievement less remarkable than it might seem at first” (Clever Hans, 109). Terrace also examined four transcripts providing data on two other signing chimpanzees, Ally and Booee. Finally, he summarizes his findings:

“Nim’s, Washoe’s, Ally’s, Booee’s, and Koko’s use of signs suggests a type of interaction between an ape and its trainer that has little to do with human language. In each instance the sole function of the ape’s signing appears to be to request various rewards that can be obtained only by signing. Little, if any, evidence is available that an ape signs in order to exchange information with its trainer, as opposed to simply demanding some object or activity” (Clever Hans, 109-110).

Following on similar criticisms by Terrace, Seidenberg and Petitto point out the simple absence of data supporting the claims that apes show linguistic competence:

“The primary data in a study of ape language must include a large corpus of utterances, a substantial number of which are analyzed in terms of the contexts in which they occurred. No corpus exists of the utterances of any ape for whom linguistic abilities are claimed” (Clever Hans, 116).

Terrace’s Nim Chimpsky, of course, is one chimpanzee for whom linguistic ability was not claimed by his researcher. It is therefore significant that the data collected on the Nim project is, by far, the most exhaustive:

“The data of Terrace et al. on Nim are more robust than those offered by other ape researchers. Although their data are limited in several respects, they are the only systematic data on any signing ape” (Clever Hans, 121-122).

If the above citation is factually correct, it means that the ape-language studies fall into two categories: (1) the Nim project, which is based upon “systematic data,” but whose researcher could find “no evidence of an ape’s grammatical competence” and (2) the rest of the projects, for whose subjects various claims of linguistic competence have been made, but none of which are based upon “systematic data.”

Another weakness in the data—one which afflicts even the Nim project—is the practice of simply deleting signs which are immediately repeated:

“In comparing Nim’s multisign utterances and mean length of utterances (MLU) to those of children, it is important to realize that all contiguous repetitions were deleted. In this respect, Terrace et al. follow the practice established by the other ape researchers. The repetitions in ape signing constitute one of the primary differences between their behaviour and the language of deaf and hearing children, yet they have always been eliminated from analyses” (Clever Hans, 123).

Needless to observe, the deletion of such uselessly repeated “words” would tend to make an ape’s recorded “speech” appear much more intelligible and meaningful than it actually is.

In a noteworthy understatement, Seidenberg and Petitto conclude, “There are numerous methodological problems with this research” (Clever Hans, 127). Even if all available data from ape-language studies—anecdotal and otherwise—were to be accepted at face value the legitimacy of claims about apes understanding the meanings of their signs, creating new word complexes, deceiving, lying, reasoning, and so forth, need not be recognized in the sense of providing proof of the possession of genuine intellectual powers on their part.

It must be remembered that contemporary electronic computers can be programmed to simulate many of these behaviours—and, probably, in principle, all of them. Walker points out some of these capabilities:

“Already there are computers which can recognise simple spoken instructions, and there are computer programs which can play the part of a psychotherapist in interchanges with real patients (Holden, 1977), so the inability of machines to conduct low-grade conversations is no longer such a strong point” (Animal Thought, 9).

If a computer can hold its own with real patients while feigning the role of a psychotherapist, it should surely be able to perform many of the functions of signing apes. Clearly, given appropriate sensing devices and robotics, even the most impressive, non-cued Savage-Rumbaugh experimental results could easily be simulated by computers—even by pairs of computers exhibiting the co-operative exchange of information and objects as was seen in the activities of the chimpanzees, Sherman and Austin (Animal Thought, 364-370, 373). This would include the ability to “label labels,” for example, to respond to the arbitrary pattern for banana by pressing the key meaning food (Animal Thought, 369-370). Such performance may seem remarkable in an ape, but it would be literal child’s play to a properly programmed computer.

Again, programming a computer to “deceive” or “lie to” an interrogator is no great feat—although Woodruff and Premack apparently spent considerable time and effort creating an environment which, in effect, “programmed” chimpanzees to engage in just such unworthy conduct (Animal Thought, 370-371).

Certainly there are, as yet, no reports about apes having learned to play chess. Yet, Walker reports:

“Pocket-sized computers are now available that can play chess at a typical, if not outstanding, human level, accompanied by a rudimentary attempt at conversation about the game… In the face of modern electronic technology, though, it is less obvious that it is impossible for physical devices to achieve human flexibility than it was in the seventeenth century” (Animal Thought, 10-11).

Evidently then, the electronic computer is capable of engaging in “low-grade conversations”—and this, probably in a manner which would well outstrip its nearest ape competitors.

While it must be conceded that all of the abovementioned capabilities of electronic computers presuppose the agency of very intelligent human computer programmers, yet the correlative “programming” of apes must be understood to occur as a result of deliberate human training, unintentional cuing, and unavoidable human influence upon the animals.

On the other hand, it must be recognized that the capabilities of apes equal or exceed those of computers in several significant respects. According to the eminent physicist-theologian Stanley L. Jaki, the number of potential memory units in the brain is phenomenal. In his Brain, Mind and Computers [BMC] (1969), he writes, “After all, the latitude between 1027, the estimated number of molecules in the brain, and 1010, the estimated number of neurons, is enormous enough to accommodate any guess, however bold, fanciful, or arbitrary” (BMC, 110). Later (BMC, 115), he tells us that “the human brain… [has] …twice as many neurons as the number of neurons in the brain of apes,” we conclude that the number of neurons in the brain of apes must be 5 X 109.

This certainly constitutes an impressive amount of almost instantaneously available “core storage.” Moreover, while it is possible to attach elaborate “sensing” devices to provide input data to a computer, nothing devised by man can match the natural abilities of the multiple external and internal senses found in higher animals, including the apes. Hence, their ability to sense and categorize a banana as food is simply part of their natural “equipment.” Finally, while extensive and complex robotic devices are now becoming an essential ingredient in various computer-controlled manufacturing processes, an ape’s limbs, hands, and feet afford him a comprehensive dexterity unmatched by that of any single machine.

The point of all this is simply that none of the performances exhibited by language-trained apes exceeds in principle the capacities of electronic computers. And yet, electronic computers simply manipulate data. They experience neither intellectual nor even sentient knowledge and, in fact, do not even possess that unity of existence which is proper to a single substance. A computer is merely a pile of cleverly constructed electronic parts conjoined to form an accidental, functional unity which serves man’s purpose.

It is in no way surprising, then, that man should be able to “program” apes to perform in the manner reported by researchers. For these apes have, indeed, become, as Heini Hediger so adroitly points out, artifacts—through the language and tasks which we humans have imposed upon them (Clever Hans, 5).

The force of much of the above argument from analogy will be lost upon those who do not understand why we state that computers possess neither substantial existence and unity nor any sentient or intellectual knowledge. Our claims may seem especially gratuitous in an age in which various computer experts proclaim the imminent possibility of success in the search for artificial intelligence through the science of cybernetics.

Yet, it would appear to be sheer absurdity to suggest that the elementary components of complicated contemporary computers—whether considered singly or in concert—could conceivably experience anything whatsoever. For no non-living substance—whether it be an atom, a molecule, a rock, or even an electronic chip—is itself capable of sensation or intellection.

On the other hand, what answer can be given to the sceptic’s seemingly absurd, but elusively difficult, query: How can we be so certain that some form of consciousness, or at least the potency for consciousness, is not present in the apparently inanimate parts used to compose a modern computer? As any novice logician is well aware, the problems inherent in the demonstration of any negative are substantive. Hence, the challenge of proving that inanimate objects are truly non-living, non-sensing, non-thinking, and so forth, is difficult—the moment, of course, that one is prepared to take the issue at all seriously.

Clearly, potentialities for sensation and intellection as well as other life activities do exist—but only as faculties (operative potencies) of already living things. These powers are secondary qualities inherent in and proper to the various living species—which properties flow from their very essence and are put into act by the apprehension of the appropriate formal object. Thus, the potency for sight in an animal is a sensitive faculty of its substantial form (soul) which enables the animal to see actually when it is put into act by the presence of its proper sense object (colour). This is not the same at all as suggesting that inanimate objects as such might possess such potencies or faculties.

Despite its apparent difficulty, though, it is indeed possible to demonstrate that the universal absence of specific life activities—both in the individual and in all other things of the same essential type—shows that those life qualities are utterly outside of or missing from such a nature. Or, to put the matter affirmatively, the presence of a given form necessarily implies its formal effects, that is, if a thing is alive, it must manifest its life activities; if sensation is a power of its nature, it must, at least at times, actually sense. That a power should exist in a given species, but never be found in act, is absolutely impossible. This fundamental truth can be shown as follows.

According to the utter certitude which is offered by the science of metaphysics, there must exist a sufficient reason why a given thing consistently exhibits certain qualities or activities, but not others. For instance, if a non-living thing, such as a rock, manifests the qualities of extension and mass, yet never exhibits any life activities, for example, nutrition, growth, or reproduction, then either such life powers must be absent from its nature altogether, or else, if present, there must be some sufficient reason why such powers are never exhibited in act. And that reason must be either intrinsic or extrinsic to its nature. If it is extrinsic, then it would have to be accidental to the nature, and thus, caused. As St. Thomas Aquinas observes:

“Everything that is in something per accidens, since it is extraneous to its nature, must be found in it by reason of some exterior cause” (De Potentia Dei, q. 10, a. 4, c.).

Moreover, what does not flow from the very essence of a thing cannot be found to occur universally in that thing—even if it be the universal absence of a quality or activity. For, as St. Thomas Aquinas also points out:

“The power of every agent [which acts] through necessity of nature is determined to one effect, and therefore it is that every natural [agent] comes always in the same way, unless there should be an impediment” (Summa Contra Gentiles, III, 23).

Hence, while an extrinsic cause might occasionally interfere with the vital activities of a living thing, such suppression of the nature’s activities is relatively rare—and surely, never universal. Thus, the ability to reproduce may be suppressed by an extrinsic cause in a few individuals in a species, but most will reproduce. On the other hand, if reproduction were absent in every member of a species, for example, rocks, then the absence of such activity must be attributed directly to the essence itself.

But if a thing is said to possess a power or potency to a certain act by its very essence, and yet, that selfsame essence is said to be responsible for its never actually exercising such a power, then such an essence becomes self-contradictory—since that essence would then be responsible both for its substance essentially being able to possess that quality and for it never being able actually to possess that same quality. The same essence would then be the reason why a thing is able to be alive or conscious and also, at the same time, the reason why that same thing is never able to be alive or conscious. This is clearly both absurd and impossible.

Moreover, Aristotle defines nature as “a source or cause of being moved and of being at rest in that to which it belongs primarily” (Physics, II, 1, 192b22-23). But a nature which would also be the reason for a thing not moving or resting would clearly contradict itself.

From all this, it follows that, if a quality or activity is lacking in each and every member of a species of things, it is absent neither by accident nor as a positive effect of the essence—but simply because such quality or activity does not belong to its essence at all. Hence, non-living things have no life powers within their natures. They can gain life powers only by undergoing a substantial change, that is, by somehow becoming assimilated into the very substance of a living thing, as when a tree absorbs nutrients from the soil and then turns them into its very self.

But such is clearly not what happens when inanimate parts are artificially joined together into an accidental, functional unity such as an electronic computer. Thus, none of a computer’s individual parts which are inanimate in themselves can exhibit the properties of life, sensation, or intellection. Nor can any combination of such non-living entities—even if formed into a highly complex functional unity—achieve the activities of perception or thought, since these noetic perfections transcend utterly the individual natures, and thus, the natural limitations, of its components.

Since it is an artificial composite of many substances, a computer constitutes merely an accidental unity. As such, no accidental perfection can exist in it which is not grounded in the natures of its constituent elements. It is a perennial temptation to engage in the metaphysical slight of hand of suggesting that somehow the whole might be greater than the sum of its parts, that the total collectivity can exhibit qualities of existence found in none of its elements. In this strange way, like Pinocchio, the computer is averred to take on suddenly all the properties of a living substance—to sense and to think.

But such is the stuff of fantasy. It is to commit the fallacy of composition—to attribute to the whole qualities found in none of its parts. It is like suggesting that an infinite multitude of idiots could somehow—if only properly arranged—constitute a single genius. The fundamental obstacle to all such speculation is the principle of sufficient reason. For the non-living, as such, offers no existential foundation for the properties of life. And merely accidental rearrangements of essentially non-living components provide no sufficient reason for the positing of the essentially higher activities found in living things—unless there takes place the sort of substantial change described above. And such substantial changes are found solely in the presently constituted natural order of things, that is, by assimilation or generation.

Since the hylemorphist philosopher understands that the substantial unity of things above the atomic level depends upon some unifying principle, that is, the substantial form, he knows that only natural unities possessing appropriate cognitive faculties of sensation or intellection can actually know anything. Thus a “sensing device” such as a television set running in an empty room actually senses nothing. It cannot see its own picture or hear its own sound. No genuine perception can occur until, say, a dog stumbles into the room and glances at the set in operation.

The dog can see and hear the set precisely because the dog is a natural living substantial unity whose primary matter is specified and unified by a substantial form (its soul) which possesses the sense faculties of sight and hearing. Absent the sensitive soul, the most complex “sensing device” knows nothing of the sense data it records. Absent the intellectual soul, a “thinking” machine understands nothing of the intelligible data it manipulates nor even is it aware of its own existence. A computer could well be programmed to pronounce, “Cogito ergo sum,” and yet remain completely unaware of its own existence or anything else.

Gödel’s Theorem

The inherent limitations of any electronic computer were unintentionally underlined by the German mathematician Kurt Gödel in 1930 when he proposed his famed incompleteness theorem to the Vienna Academy of Sciences. As theologian and physicist, Stanley L. Jaki, S.J., simply expresses it, the theorem states “that even in the elementary parts of arithmetic there are propositions which cannot be proved or disproved in that system” (BMC, 214). Gödel himself initially vastly underestimated the profound implications of his theorem. Among these were (1) that it struck “a fatal blow to Hilbert’s great program to formalize the whole of mathematics…” (BMC, 215) and (2) that it “cuts the ground under the efforts that view machines… as adequate models of the mind” (BMC, 216).

Jaki spells out the impact of the incompleteness theorem on the question of computer consciousness:

“Actually, when a machine is requested to prove that “a specific formula is unprovable in a particular system,” one expects the machine to be self-conscious, or in other words, that it knows that it knows it, and that it knows that it knows it that it knows it, and so forth ad infinitum…. A machine would always need an extra part to reflect on its own performance, and therein lies the Achilles heel of the reasoning according to which a machine with a sufficiently high degree of complexity will become conscious. Regardless of how one defines consciousness, such a machine, as long as it is a machine in the accepted sense of the word, will not and cannot be fully self-conscious. It will not be able to reflect on its last sector of consciousness” (BMC, 220-221).

Despite the logical adroitness of this analysis, we must, of course, remember that in truth and in fact machines possess no psychic faculties at all. They actually have neither even the most immediate level of reflection nor any form of consciousness whatever.

What Gödel’s theorem simply implies is that men are not machines—that computers (because they have not a spiritual intellect) are unable to know the truth of their own “judgments” since they lack the capacity for self-reflective consciousness.

This analysis of computer deficiency based upon the incompleteness theorem is offered simply to demonstrate that, although computers may be able to simulate the abilities of language-trained apes, their computations, nonetheless, remain essentially inferior to human cognitive abilities. In truth, neither apes nor computers are capable of genuinely self-reflective acts of intellection since such acts are possible for creatures with spiritual intellects alone, for example, man. Unlike computers, apes, of course, are alive and possess sensitive souls capable of sense consciousness—but not intellection.

Nonetheless, the fact that electronic computers—having neither sensation nor intellection nor even life itself—could, in principle, be designed and programmed so as to imitate, or even exceed, the skills of language-trained apes is sufficient evidence that ape-language studies pose no threat to man’s uniqueness as a species. Nor do the studies cast in any doubt man’s uniquely spiritual nature—as distinguished from the rest of the animal kingdom.

One striking bit of information drawn from the history of ape- language studies has been saved until this point in our study in order to underscore the radical difference between man and lesser primates. It demonstrates, as Paul Bouissac points out, that the animal’s perspective on what is going on may differ radically from our own. Now, no language-trained ape possesses a greater reputation for linguistic expertise and presumed civility than the female chimpanzee, Washoe. It is therefore rather appalling to learn of the following incident reported by Bouissac:

“There are indeed indications that accidents are not infrequent, although they have never been publicized; the recent attack of the celebrated “Washoe” on Karl Pribram, in which the eminent psychologist lost a finger (personal communication, June 13, 1980) was undoubtedly triggered by a situation that was not perceived in the same manner by the chimpanzee and her human keepers and mentors” (Clever Hans, 24).

In pointing to the divergence of perspective between man and ape, Bouissac may well understate the problem. Washoe would have been about 15 years old at the time of the attack. Needless to say, humans of that age have virtually never been recorded as even attempting to bite their teachers—and this would seem especially true of outstanding students!

This clear-cut evidence that animals—even apes—simply do not perceive the communicative context in the same way that man does demonstrates the degree to which the anthropomorphic fallacy has overtaken many researchers—despite their claims of caution in this regard.

A Positive Demonstration

While much of the preceding discussion pertinent to man’s uniqueness as a species has focused upon signs of his spiritual nature and, to an even greater degree, upon the failure of lower animals to demonstrate any intellectual ability, philosopher and theologian Austin M. Woodbury, S.M., approaches the question with a fresh and more decisive perspective (Natural Philosophy, Treatise Three, Psychology [1951], III, Ch. 40, Art. 2, 432-465).

He points out that the effort to explain all animal behaviour in terms of sensation alone could never be completed and might produce no more than a probable conclusion because of the complexity of the task. One need only consider the endless anecdotal data to be examined (Psychology, 437).

To avoid the logical weakness of this negative approach, Woodbury proposes an appropriate remedy by seeking direct and positive proof that brutes are lacking in the necessary effects or signs of intelligence (Psychology, 438).

For, he argues, the necessary effects of intellect are four: speech, progress, knowledge of relations, and knowledge of immaterial objects. Since each of these is a necessary effect, “if it be shown that even one of these signs of intellect is lacking to ‘brutes’, then it is positively proved that ‘brutes’ are devoid of intellect” (Psychology, 438). In fact, Woodbury argues that brute animals are in default in all four areas.

While the most significant ape-language experiments were conducted after Woodbury wrote his Psychology, nonetheless his insistence on the absence of true speech among brute animals remains correct as we have seen above. He points out that animals possess the organs of voice (or, we might note, the hands to make signs), the appropriate sensible images, and the inclination to manifest their psychic states—but they do not manifest true speech since they lack intellect (Psychology, 441).

What Woodbury seems to be saying is that, if brute animals actually possessed intellect, they would have long ago developed their own forms of communication expressed in arbitrary or conventional signs. Their failure to do so is manifest evidence of the absence of intellect. On the contrary, since all men do possess intellect, all men develop speech.

It is noteworthy that even a chimpanzee brought up in a human family learns no speech at all whereas a human child does so easily and quickly. While it is conceded that chimpanzees and other apes lack the vocal dexterity of man, yet it must be noted that they do possess sufficient vocal equipment to enable them to make limited attempts at speech—just as would any human suffering from a severe speech defect. Yet, apes attempt nothing of the sort.

While Woodbury does not, of course, make reference here to the signing apes, it is clear that their behaviour is to be explained by imitation and the association of images. While man may impose signing upon such animals artificially, their failure to have developed language on their own and in their natural habitat demonstrates lack of true speech. That animals possess natural signs is conceded, but irrelevant.

Neither do animals present evidence of genuine progress. Woodbury points out that “from intellect by natural necessity follows progress in works, knowledges and sciences, arts and virtue” (Psychology, 443) While he grants that animals do learn from experience, imitation, and training, yet, because they lack the capacity for intellectual self-reflection, they are unable to correct themselves—an ability absolutely essential to true progress.

Even in the most “primitive” societies, true men make progress as individuals. For children learn language, arts, complex tribal organization, complex legal systems, and religious rites (Psychology, 444). Woodbury notes, “Moreover, the lowest of such peoples can be raised by education to very high culture” (Psychology, 444).

Woodbury points out that the appetite to make deliberate progress is inherent in a being endowed with intellect and will. For as the intellect naturally seeks the universal truth and the will seeks the infinite good, no finite truth or good offers complete satisfaction. Thus man, both as a species and as an individual, seeks continually to correct and perfect himself. While apes are ever content to satisfy the same sensitive urges, men erect the ever-advancing technology and culture which mark the progress of civilization. The failure of animals to make anything but accidental improvements—except when the intellect of man imposes itself upon them through training—proves the utter absence of intellect within their natures.

Commenting on his third sign that intellect is lacking in animals, Woodbury observes that brute animals lack a formal knowledge of relations. They fail to understand the means-end relationship in its formal significance. And, while men grasp the formal character of the cause-effect relationship in terms of being itself, animals are limited merely to perceiving and associating a succession of events (Psychology, 445).

Woodbury distinguishes between possessing a universal understanding of the ontological nature of means in relation to ends as opposed to possessing a merely sensitive knowledge of related singular things. Lower animals reveal their lack of such understanding whenever conditions change so as to make the ordinarily attained end of their instinctive activity unobtainable. For they then show a lack of versatility in devising a substitute means to that end. Also, they will continue to repeat the now utterly futile action which instinct presses upon them. Woodbury offers this example:

“Thus apes, accustomed to perch themselves on a box to reach fruit, if the box be absent, place on the ground beneath the fruit a sheet of paper and perch themselves thereupon” (Psychology, 447).