Background to the “Creation” Dispute

There is nothing very new about the thesis of this article—for many proofs that God is Creator of all finite things have already been attempted—often with great success. Moreover, we know as an article of Catholic faith that the existence of God can be known with certainty by the light of natural human reason (Denzinger’s Enchiridion Symbolorum, 1806). Yet, what may be somewhat novel about this article is that I will attempt to prove God’s existence by means of a series of diverse considerations about the very meaning of the term, “creation.” Moreover, I will examine certain presumptions about creation which have been made by atheists, i.e., by those who deny the very conclusion which is presently being sought.

Any self-respecting atheist must deny that the world is created by God. And yet, this very fact, namely, that the atheist feels called upon to deny the reality of creation, is itself significant—so much so, that this universal reaction of atheism will itself serve as the point of departure for our investigation.

Astronomer Robert Jastrow has commented upon the strange situation now confronting his fellow astronomers (many of whom appear to be scientific materialists). Jastrow observes, “…I am fascinated by some strange developments going on in astronomy—partly because of their religious implications and partly because of the peculiar reactions of my colleagues” (Robert Jastrow, God and the Astronomers,1978, 11).

Jastrow proceeds to explain the enigma confronted by modem scientists:

”The essence of the strange developments is that the Universe had, in some sense, a beginning—that it began at a certain moment in time, and under circumstances that seem to make it impossible—not just now—but ever—to find out what force or forces brought the world into being at that moment…. the astronomical evidence proves that the Universe was created twenty billion years ago in a fiery explosion, and in the searing heat of that first moment, all the evidence needed for a scientific study of the cause of the great explosion was melted down and destroyed” (God and the Astronomers, 11-12).

More recent estimates of the time of the universe’s birth now place it some 13.7 billion years ago.

Scientists today pursue the vision of Grand Unified Theories which attempt to unify the fundamental forces of nature as different aspects of the same force. Senior physicist at the Argonne National Laboratory’s High Energy Physics Division, David S. Ayres, remarks that the “Grand Unified Theories offer detailed insight into the processes which occurred at the instant of creation ….” (Argonne News, 1984, 8-9).

For centuries, atheistic materialists had blandly assumed the eternity of the world while denigrating the peculiarly Judeo-Christian belief of creation in time as a vestige of religious mythology. Science seemed squarely in the atheist’s corner until the recent advent of the Big Bang theory—a theory whose scientific underpinnings have come to be regarded by most scientists today to be quite secure. The 1965 discovery of the apparently vestigial fireball radiation of the Big Bang by Amo Penzias and Robert Wilson of the Bell Laboratories has left the theory, at the present time, with “no competitors” according to Jastrow (God and the Astronomers, 14-16).

Small wonder, then, the “peculiar reactions” of many astronomers, as noted’ by Jastrow! What he refers to are the efforts made by many of his fellow scientists to ignore and refute the mounting evidence in favor of the Big Bang.

Jastrow describes the situation thus:

“Theologians generally are delighted with the proof that the Universe had a beginning, but astronomers are curiously upset. Their reactions provide an interesting demonstration of the response of the scientific mind—supposedly a very objective mind—when evidence uncovered by science itself leads to a conflict with the articles of faith in our profession. It turns out that the scientist behaves the way the rest of us do when our beliefs are in conflict with the evidence. We become irritated, we pretend the conflict does not exist, or we paper it over with meaningless phrases” (God and the Astronomers, 16).

The reactions to the possibility of a Big Bang began shortly after World War I—and from a rather surprising quarter:

“Around this time, signs of irritation began to appear among the scientists. Einstein was the first to complain. He was disturbed by the idea of a Universe that blows up, because it implied that the world had a beginning” (God and the Astronomers, 27).

It is not here suggested that Einstein and all others who opposed the Big Bang theory were atheists. Certainly, Einstein himself appears to have embraced the conception of God propounded by Spinoza (God and the Astronomers, 28).

And yet, conversely, it is manifestly evident that scientific materialists would be in the forefront of those astronomers who would feel uncomfortable in the face of a new theory which seemed to challenge their most fundamental convictions. While it is not suggested that the physical theory of the Big Bang necessarily implies the theological doctrine of creation, nonetheless it is quite understandable that even the appearance of such an implication should cause more than a ripple of resistance among those both philosophically and scientifically indisposed to the notion of creation in time. Yet, we shall see that our concern in this paper will extend to a much broader notion of creation—a notion not restricted merely to that of “having a beginning in time.”

In point of fact, just when most of the scientific community has gotten comfortable supporting the relatively recent Big Bang theory, we are suddenly reminded by new evidence that the history of science is littered with the intellectual corpses of bygone universal beliefs. True science is never dogmatic. What actually happens is that a generally accepted scientific hypothesis is sometimes greeted by new sets of data that contradict its basic premises and soon a new, and quite different, scientific hypothesis replaces the formerly reigning one.

We now learn that findings from the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) appear to contradict the “standard model” for galactic expansion, which has accompanied the Big Bang hypothesis. It turns out that distant celestial objects, now being seen for the first time through the use of the JWST, do not conform to Big Bang expansion model expectations. Instead of distant galaxies being huge and having a certain amount of “red shift” in their light, the Webb telescope is showing us the exact opposite! The number of disc galaxies is some ten times that of standard galaxy expansion models. Moreover, distant galaxies are being found to be unexpectedly smooth, small, and old. In fact, more and more data seems to contradict what had been predicted based on the massive galactic expansion model assumed to follow from the Big Bang.

This has led some astronomers to actually reject the Big Bang hypothesis altogether!

Still, two points must be made clear:

- While frequently associated theses, the fact remains that the Big Bang hypothesis is separate from the cosmic expansion model. Moreover, the Webb telescope data does not in itself address the cosmic microwave background radiation which has long been taken as evidence for the Big Bang.

- For purposes of this article, much more important is the fact that the Big Bang hypothesis belongs to the subject matter of natural science, not philosophy. Contending physical hypotheses concerning the origin and development of the universe must be evaluated by astronomers and other physical scientists. That is not my task. Philosophically, I will show that, whether the universe began in time or not is entirely irrelevant to the philosophical question of whether it is created by God.

I need to determine the proper philosophical meaning of “creation” as well as whether the universe was created in that properly philosophical meaning.

The Eternal Enigma

The central question which this article seeks to address is simply the age old puzzle: “Why does anything exist at all?” The believer immediately responds with a simple affirmation of his faith: “Things exist because God exists to make them.” But the atheist is driven to the logical alternative of insisting on the aseity of the Universe: “Things simply explain their own existence; their very fact of existing is its own explanation. Moreover, the Universe has always existed in some form or other, and hence, needs no God to have created it.” Some atheists and agnostics attack the principle of explanation itself, suggesting that not everything may need a sufficient reason or that, perhaps, the principle is limited in scope to the observable phenomena.

In one of human intellectual history’s less ingenuous moments, Karl Marx simply refuses to grant intellectual legitimacy to any question put to the very existence of the world. He labels such inquiry “…perverse…” since it implies “…the inessentiality of nature and of man …. ” Marx insists that for socialism “…the real existence of man and nature has become practical, sensuous and perceptible…” and, hence, such a question “…has become impossible in practice” (Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, 1961, 112-114).

Still, examples of those willing to address directly the central issue are not difficult to find. The problem as to why things exist at all is clearly posed by Kai Nielsen (who was himself an atheist):

“Indeed, ‘Why is there anything at all?’ is an odd question, but in certain philosophical and perhaps even religious moods it is natural to ask: Why is it that any of the things that make up the universe actually exist? They do, of course, but why is this so? There might have been nothing at all!” (Kai Nielsen, Reason and Practice: A Modern Introduction to Philosophy, 1971, 180).

Or again, as F.E. Copleston put it in his famous 1948 British Broadcasting Corporation debate on the existence of God with Bertrand Russell:

“Well, I can’t see how you can rule out the legitimacy of asking the question how the total, or anything at all comes to be there. Why something rather than nothing, that is the question?” (The Existence of God, ed. John Hick, 1964, 175).

John Hospers puts succinctly the theistic response to the given existence of the world (not that he holds it himself):

“Why, indeed, does any universe at all exist—why is there a universe at all rather than simply nothing? For this you have no explanation at all. But I do. I hold that there is a necessary being, God, and that since he exists necessarily all contingent existents (and that includes everything in the universe) owe their existence to this necessary being and are explained by the fact that this necessary being exists” (John Hospers, An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis, 2nd edition, 1967), 440.

But in a contrary response to this same most basic question, as Roy Wood Sellars puts it,”…the modem materialist stresses the aseity as against the contingence notion of creationalism” (A History of Philosophical Systems, ed. Vergilius Ferm, 1950, 425).

The meaning for the materialist of this “aseity” is put with clarity by Nielsen: “…all other realities, if such there be, depend for their existence on these physical realities, but these physical realities do not depend on any other realities for their own existence” (Reason and Practice, 334).

Hospers elucidates in his own manner the claim that the universe simply explains itself and needs no further explanation:

“…this is just a “brute fact”—the universe has such-and-such laws, and if those are ultimate (underived), we can’t derive them from any other ones….If we have once arrived at a basic or underived law (not that we ever know that we have), then it is self-contradictory to ask for an explanation of it” (An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis, 442).

What Hospers means here is that the ultimate laws of the universe, by definition as ultimate, require no further explanation. They are self-explanatory.

Again, Anthony Flew challenges the position that God is any greater an intelligible explanation of the universe that is the universe itself:

“No reason whatever has yet been given for considering that God would be an inherently more intelligible ultimate that—say—the most fundamental laws of energy and stuff; much less for postulating the actual existence of such a further and extraordinary entity, instead of somehow contenting yourself with the alternative idea that the world we know is—in the vertical dimension-not dependent on anything else, and that it is also, in some state or other, probably eternal and without beginning” (Anthony Flew, God: A Critical Enquiry, 96).

The atheistic alternative explanation to claiming that the universe is its own explanation is the claim that not everything needs an explanation. That is to say, the principle of sufficient reason itself is attacked. Again Nielsen puts the case succinctly:

“It would only follow that there is a necessary being if it were true that there is a complete explanation that would give us an adequate explanation of why anything exists at all. Why should we assume or even believe that we actually have such an explanation?”

“It is certainly very natural to reject the principle of sufficient reason and to say that it has not been established that there must be or even that there is (if only we could discover it) an explanation for everything. Some events or states of affairs may never be explained. There may even be some things that are inexplicable” (Reason and Practice, 181).

I do not intend here to reiterate and refute the monumental errors of idealism and process philosophy which provide the most substantive attacks on the principles of sufficient reason and causality. Those who sincerely seek the most exhaustive and convincing defense of these principles are referred to Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange’s classical treatment in the latter part of the first volume of God: His Existence and Nature (1934, 181-194). I have offered my own defense of these transcendental first principles on the Strange Notions website.

It suffices to point out that it seems a bit hypocritical that scientific materialists should ultimately retreat behind a denial of rational principles when it is they who dare to mock all others as being “irrational” and “unscientific.” It is indeed curious that those who demand a scientific explanation for everything should, in this singular instance, fail to see the need for any explanation whatever! One cannot but compare such selective abandonment of rational principles to the curious biological doctrine that spontaneous generation never occurs except, of course, when the evolutionist has need of it in order to initiate the process of evolution itself!

In the end, the consensus of atheists and theists who address the basic question of existence, as well as the dictates of right reason, present the following stark alternatives: Either God (the Infinite Being) exists, or else, the world (all finite being) explains itself, or else, not all things have full explanations. It is our contention that the latter two alternatives are not only absurd, but impossible.

“Creation” as Expression of Infinite Power

For those scientific materialists who refuse to follow the intellectually suicidal denial that there must be reasons for things, the universe must be conceived as self-existent, that is, it somehow explains itself. Moreover, these atheistic materialists clearly accept the metaphysical principle that “…from nothing, nothing comes to be….” (St. Thomas Aquinas, in I Physics, 14, n. 2), since they universally deny that the cosmos had an absolute beginning in time. Thereby they implicitly acknowledge that a universe which just “pops into” existence (out of no pre-existent state) is not only absurd, but impossible.

While it is evident that the natural intuition of the laws of being would require every intellect to affirm that being (the world) can only come from pre-existent being (a prior state of the world, or God), why is it the case that the reason of virtually every man, theist and atheist alike, sees in the notion of instantaneous creation of the world (out of nothing and using nothing) the exclusive mark of divinity itself? With but a modicum of metaphysical reflection, the human mind—theist and atheist alike—grasps that the act of creation is intelligible only as an expression of power—infinite power. And it is precisely this manifestation of power without measure which commands intellectual assent to the existence of God (in the traditional meaning of the term) as the sole adequate explanation or foundation for such power.

The average person who considers the matter will express the insight as follows: “To make something out of nothing can only be the act of an infinitely powerful being, God.” The professional theologian or philosopher will render this insight with greater precision by saying: “That something should come to be while presupposing no pre-existent matter or subject requires the infinite power of God.”

In each case what is affirmed is the absolute need for unlimited power as the only adequate explanation for the universe beginning to be in time. Yet the question remains, “How can we be so certain that the ‘popping into existence’ of the world requires the existence of an all-powerful God?” Is this inference simply the product of a primordial insight or intuition which is, at root, rationally indefensible? Are we ultimately reduced to a form of fideism here?

Still, if this be fideism, then the atheist must suffer it as well — given the firm tradition of atomistic materialism, tracing all the way back to Democritus in the fifth century B.C., which assumes that the universe has always existed, never having a beginning in time. That is why so many scientists held out long for the Steady State theory, which holds that the universe is eternal and largely unchanging.

Why Creation Requires Infinite Power

While there appears to exist a nearly universal intuitive recognition that the act of creating requires the infinite power of a Supreme Being, the attempt to give intellectual justification to this primordial insight is fraught with difficulty. For, even if one grants that the existence of the world had an absolute beginning in time and that this beginning must have an adequate explanation, it is not at once clear precisely why this phenomenon requires an infinitely powerful cause.

Is it because being infinitely transcends non-being? But then, the being of the world is itself only finite (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 7, aa. 2-4). Perhaps, alternatively, one should focus upon the fact that between non-being and being there is no middle ground. Hence the act which transcends this “gap” between non-being and being must be considered as literally immeasurable. Yet, no reputable thinker would dare to refer to a real relation between non-being and being—since a real relation always requires two real terms, and non-being is not real. In Summa Theologiae, I, q. 13, a. 7, c, St. Thomas refers to the merely logical character of the “… relations which are between being and non-being, which reason forms, insofar as it apprehends non-being as a certain extreme.” Hence, the metaphors about “transcending an infinite gap” from non-being to being begin to sound suspiciously poetic or mystical.

It is necessary to turn to the Common Doctor of the Church for illumination of a precise, scientific conception of exactly why creation requires infinite power. The following is neither poetry nor mysticism:

“It must be said that the power of the maker is measured not only from the substance of the thing made but also from the way of its making; for a greater heat not only heats more, but also heats more swiftly. Thus, although to create some finite effect does not demonstrate infinite power, nevertheless to create it from nothing does demonstrate infinite power…. For if a greater power is required in the agent insofar as the potency is more remote from the act, it must be that the power of an agent (which produces) from no presupposed potency, such as a creating agent does, would be infinite; because there is no proportion of no potency to some potency, as is presupposed by the power of a natural agent, just as there is no proportion of non-being to being” (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 45, a. 5, ad 3).

The principle which St. Thomas employs here is laid down when he says, “…a greater power is required in the agent insofar as the potency is more remote from the act…” For, as power means the ability to produce being or to act, its measure is taken not merely from the effect produced but also from the proportion between what is presupposed by the agent in order to produce the effect and the effect produced.

Thus, to make a chicken from pre-existing chickens requires a certain measure of power. But to produce a chicken from merely vegetative life would require even greater power; and to produce a chicken from non-living matter yet greater power. But to produce a chicken while presupposing no pre-existent matter at all clearly would require immeasurably greater power. It is immeasurable, as St. Thomas points out, precisely because “…there is no proportion of non-being to being.”

Note that this argument does not rest upon an attempt to measure any supposed infinite relation between non-being and being. Rather, it is precisely the absolute lack of any relation whatever between non-being and being which demands an infinite power to create. For it is precisely the proportion of the potency to act which is measurable. The greater the distance (not physical distance, but remoteness or distinction in existence) between the potentiality and its act, the greater the power needed to actualize that potency. But such a proportion between some presupposed potentiality and its act is always measurable (in some sense), and therefore, is finite—since it is of the essence of the measurable to be finite and since a thing is measured only by its limits. But where there is no proportion, as between non-being and being, there can be no measure, and thus, no limit. The power required in that case knows no measure and no limit. It is therefore infinite.

Note well that St. Thomas does not argue from the remoteness of the potency from the act in the case of creation. Rather, he considers the “… proportion of no potency to some potency…”—for a creating agent presupposes no potency whereas a natural agent always presupposes some potency. He observes that there exists no such proportion just as “… there is no proportion of non-being to being.” A fortiori, the remoteness of no potency to the act of already created being becomes even more immeasurable (if that were possible).

Thus we have the rational explanation for the universal metaphysical intuition that it would require infinite power to create ex nihilo.

The True Meaning of “Creation”

If it were necessary to prove creation of the world in time in order to demonstrate the existence of God, it appears that such a task could never be accomplished by unaided natural reason. For even the most famous Christian apologist for God’s existence, St. Thomas Aquinas, concedes that reason alone cannot prove creation in time: it is simply an article of Catholic faith which is neither contrary to, nor demonstrable by, natural reason (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 46, aa. I-3; De Potentia Dei, q. 3, aa. 14 and 17; On the Eternity of the World, 1964, 2-73).

In fact, according to St. Thomas, the world could well have existed from all eternity—and yet it would still be a creature of God (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 46, a. 2, ad. I; Etienne Gilson, Elements of Christian Philosophy, 1963, 214).

One of his famous Five Ways to prove God’s existence, the Third Way, presupposes this very possibility in the logic of its argumentation. In fact, in Summa Contra Gentiles, I, 13, St. Thomas insists “… that the most efficacious way to prove God to exist is not on the supposition of the newness of the world, but rather on the supposition of the eternity of the world.” Thus, our belief in creation in time is just that—a matter of reasonable Christian belief.

The point of all this is simply to observe that, for St. Thomas, the notion of creation is quite distinct from the notion of beginning in time. After all, on the very supposition of an eternally existent God, could one deny the possibility that such a Being may have been creating the world from all eternity? And would not such a world be a creature in virtue of its being an effect of God despite its beginningless duration? In such a case, creation would be an ongoing production of the being of the world by God—with absolutely no reference to a beginning in time.

Moreover, grant that God did create the world in time. What then would be the relationship of the world to God in the next instant after the moment of creation? Or, the next day, or year, or twenty billion years? Could God cease causing the world and yet the world continue to exist? Certainly not. For, as St. Thomas observes, “With the cause ceasing, the effect ceases” (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 96, a. 3, ob 3. Also, “Removing the cause removes the effect,” Summa Theologiae, I, q. 2, a. 3, c). Creation must not be conceived as a once and for all time act. God must continue to create, or else, the cosmos would at once fall back into the nothingness from which it came (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 104, a. 1). St. Thomas refers to this continued act of creation as “conservation.”

“It must be said that the conservation of things by God is not through some new action, but through a continuation of that action by which He gives existence, which action is indeed without motion and time” (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 104, a. I, ad 4).

In other words, a proper understanding of the term “creation” is conceptually distinct from the notion of “beginning in time.” For St. Thomas, the world is created, not because it began in time, but because of its radical dependence on the Supreme Being during every moment of its existence—past, present, or future.

We are thus left with three alternatives regarding the existence of the world: Either it came to be in time—thereby requiring an infinitely powerful Creator, or else, it has existed from all eternity as the created effect of that Creator, or else, it has existed from all eternity without the causation of such a Creator.

On the first two suppositions, the existence of an infinitely powerful God is at once granted and this investigation is ended. But it is the third alternative which now requires closer scrutiny.

For the existence of the world is itself an act whose being demands some explanation. Existence is an act. It is the very first act of any substance (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 104, a. 1, ad 3). And no substance is explained unless and until its substantial existence has been accounted for. Thus we may properly inquire as to the explanation of the existence of this finite world in which we find ourselves.

When we inquire as to the explanation or sufficient reason for a supposedly uncaused finite universe, it becomes at once clear that the need for some foundation in an infinitely powerful being is not escaped. For, just as there is no pre-existing potency for such a world which is created in time, so too, there is no pre-existing potency against which to measure the actually existing universe even if it has always existed (as atheists insist). Hence, its existential foundation, even if this is not conceived as a cause outside its own being, must manifest a power which knows no measure, i.e., it is infinite.

To put the matter in other terms, the power required to explain a being (or beings) is not dependent on whether that being is an effect (whether or not such effect happens to be produced in time). Rather, such power must be measured in terms of its being the reason why there is being rather than non-being. And, as St. Thomas points out, “…there is no proportion of non-being to being” (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 45, a. 5, ad 3). Hence, the power requisite to explain the existence of the cosmos knows no measure — whether it began in time or not. Immeasurable or infinite power is needed to explain any existence at all — of anything.

But the world is clearly finite—since space and time are the limiting modes of material existence. Since the finite clearly cannot contain the infinite power needed to explain its own existence, it is evident that an infinite Being must exist.

Some Final Reflections

It may well be suspected that the foregoing demonstration of God’s existence is simply a variation of St. Thomas’s Third Way of the Summa Theologiae, I, q. 2, a. 3, c., or else, perhaps, the argument which many have abstracted from his proof for God’s eternity which is presented in the Summa Contra Gentiles, I, 15. Yet it should at once be evident that neither of these demonstrations proceed from the same starting point as the present analysis. For, both of the aforementioned texts of St. Thomas take as their initial data the existence of things which are possible to be or not to be. But the present argument proceeds neither from the possibility nor from the necessity of the world—merely from its existence and from the need for a sufficient reason for said existence.

If it were possible for the world to be its own reason for existing, then there would be no need to posit the existence of a transcendent God. It is only when it is shown that the existence of anything at all requires infinite power that it becomes evident that the finite cosmos necessarily requires an Infinitely Powerful Being as the only adequate explanation of its existence.

Hence, the present argument proceeds, not from the possible, as such, but from an analysis of the creative power implicit in any being whatever—whether it be possible or necessary, finite or infinite. It is the factual existence of things which is at issue here, not their indifference to existence.

But it is precisely that indifference to existence manifested by the possibles which St. Thomas uses to prove their causal dependence. As he puts it in the context of the Contra Gentiles:

“Everything however which is possible to exist has a cause, since it is from itself equally [related] to two [contraries], namely, existence and non-existence. [Therefore,] it must be, if it appropriates to itself existence, that this is from some cause” (Summa Contra Gentiles, I, 15).

Again, the same point is made in the Third Way when St. Thomas insists “…that which is not does not begin to be, except through something which exists” (Summa Theologiae, I, q. 2, a. 3, c).

In both these cases, again, St. Thomas reveals the causal dependence of the possibles. But the present proof seeks not to reveal causal dependence except as incidental to the need for infinite power as the sole adequate foundation for all existents. Perhaps this point could be more adequately expressed by saying that God Himself, who is absolutely uncaused, nonetheless requires infinite power in order to render His own existence intelligible. That is why St. Thomas’s task in the aforementioned contexts differs from that of the present article.

In conclusion, the intellectual exploration completed in this article entails the following central points:

First, it was established that there exists, either explicitly or implicitly, among theists and atheists alike, a universal intellectual recognition that the theological notion of an absolute beginning in time of the world entails a creation ex nihilo whose sole adequate explanation would be an Infinitely Powerful Being, or God in the traditional sense of the term.

Second, the concept of “creation” itself was scrutinized so as to reveal that it may be properly distinguished from any notion of “beginning in time”—thereby demonstrating that the mere existence of any being whatsoever entails the presence of an act (esse) which requires infinite power to be posited “outside of nothingness.” (The central metaphysical task of this article has been to establish the philosophically scientific validity of this second step.)

Third and last, it was seen that such infinite power clearly cannot reside in any finite being and, that, therefore, it is absolutely necessary to admit the existence of an Infinitely Powerful Creator as the sole adequate explanation of the finite world.

The notion of “explanation” does not necessarily denote extrinsic causality in every case. While every being requires a sufficient reason, only those beings whose sufficient reason for existing is not totally within itself would require an extrinsic sufficient reason or what is called a “cause.” This means that, while an infinitely powerful God is required to cause the existence of all the finite beings in this finite world, yet God can still be said to be his own explanation, and yet not his own cause, since he is his own intrinsic sufficient reason for being.

Dr. Dennis Bonnette retired as a Full Professor of Philosophy in 2003 from Niagara University in Lewiston, New York, where he also served as Chairman of the Philosophy Department from 1992 to 2002. He received his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Notre Dame in 1970. He is the author of two books, Aquinas’ Proofs for God’s Existence, and Origin of the Human Species, as well as many scholarly articles. [A, earlier version of this article appeared in Faith & Reason, 11:3-4 (1985), 250-63. Permission to print kindly granted by Christendom Educational Corporation, Christendom College, Front Royal, Virginia, 22630.]

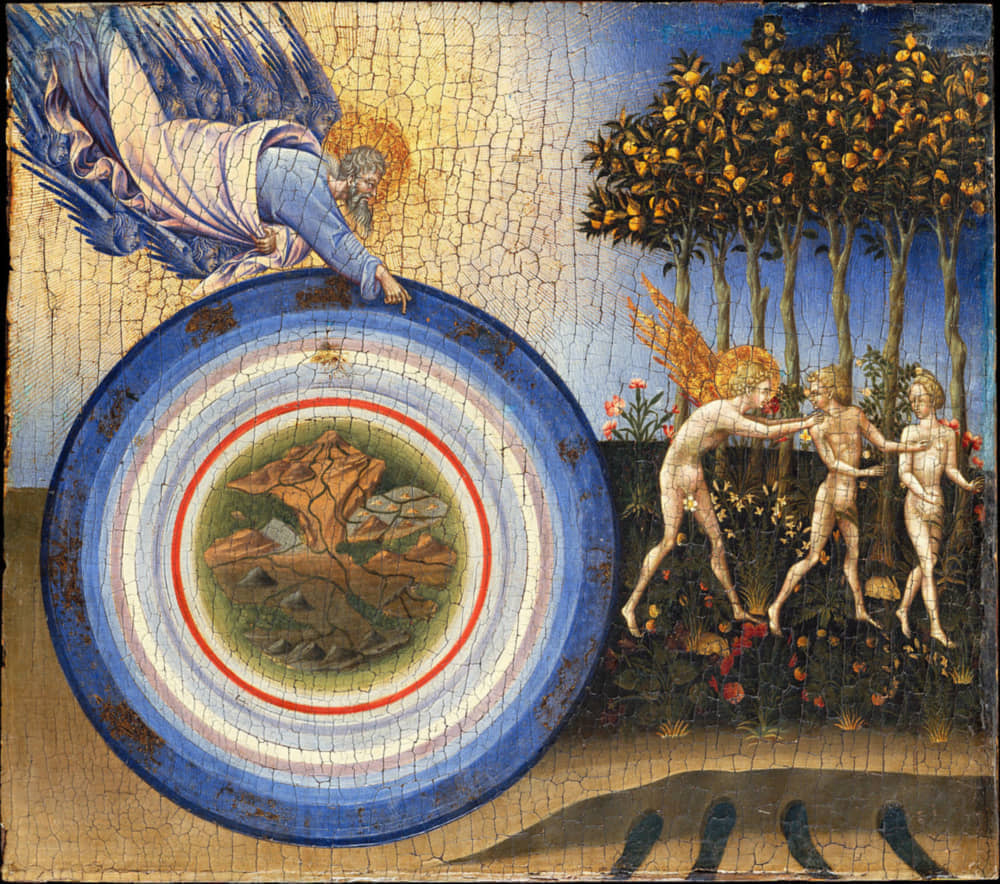

Featured: “The Creation of the World and the Expulsion from Paradise,” by Giovanni di Paolo; painted in 1445.