Setting Out

One of the features which has accented Apocatastasis Institute from the word go has been the inclusion of the Divine Office in our daily schedule. I mean in this essay to explain why this is. Other and better men have done other and better jobs at explaining what the Office is, its mechanics, history, and spirituality. We are not rehashing that necessary material here. If you are deficient in those sciences, dear reader, put aside this paper and digest those topics before returning. By way of house rules, I will be using the terms Divine Office, the Office, the Discipline, the Liturgy Of The Hours, the Prayer (with a capital p), and the Liturgy (with a capital L) interchangeably.

In this exploration we will look at the Divine Office as a medicine for social wounds, one that is rightly administered in a school setting as schools ought to be directed toward this same end. It is a salve for the wounds of secularism, abstracted pedagogy, personal foibles, and historical accidents. Like any treatment it does not contain the totality of the solution. It nudges, it points, it guides towards the correction.

The Sickness

We are unrooted. Just as one’s posture can be thrown off by flat feet or a bum knee, from unrootedness come a flurry of other ills such as a low trust society, lack of agency, and discouragement. Exploiting these social and personal failures are unscrupulous men operating in unscrupulous combinations. Foundations once destroyed, what can the just do (cf. Ps.10/11)?

Part of our unrootedness stems from economic developments at first affecting Western man, and after the Second World War, all mankind. Part of this condition stems from deliberate schemes to make unrooted men. Modern education, marital laws, and telephonic communication, for example, appear deliberately to trip up natural personal, familial, and social harmony. Part of our unrooted condition is our own concupiscence, particularly our going with the flow of deracinating and deracinated culture. We may blame social institutions all we like, but at a certain point we must hold ourselves responsible for our cooperation with McWorld. The Office is a skeleton upon which to hang real life once more, and a school setting is an opportune place to do this. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and McWorld wasn’t either. If we are to build Christendom, we will need discipline. Hour by hour, brick by brick, the Divine Office is an handy trowel for this erection.

The Myopia of Alt Ed

When I was a little bit younger, I was quite enamored with the educational critique of homeschoolers and unschoolers. To a certain

extent my subsequent exasperation with those communities is that they have not developed their insights into anything more significant than personal necessity. Singular interest is the mark of an immature mind. It is the manful intellect which grasps that the individual is a cell of a larger society; it is the manful body which labors to bring this about.

Howsomeever, I remember at one conference a mot just out of high school—or at least she was of that age, as unschoolers of course don’t go to high school—was asked how to make unschooling more popular. I’ll never forget what she said; it was wisdom in a nutshell, for all true wisdom is pithy. The girl said she didn’t want unschooling to become popular because more people would necessarily mean a watering down of that modality.

Well, she was right. For those of us who have dedicated our energies towards alternative education, we ought to have been careful what we wished for. Our educational critique has become popularized, and much of that critique has become sloganized. As so often happens in history, the subtleties of maxims which slogans assume are lost over time and after a while only the naked maxims are known without the scaffolding of assumptions the sayings originally assumed.

Thus, in Rabbinic Judaism their concept of “the Torah” migrated from the Pentateuch to first include, then prefer, the Talmud. This enlarged “Torah” became unwieldy and was condensed into a third collection, the Gamara, before the rebbes ignited a “back to sources” reaction which began the same cycle of condensation-cum-back to basics cycle again.

In the same way the Christian Fathers were summarized in the Summa and Sentences of Scholasticism which were further condensed into catechisms before triggering a “back to sources” Reformation which shortly found—to the horror of its instigators—that the meaty “Sola Scriptura” rule of thumb was being taken literally. Likewise, the educational critique has fallen fast and far in the last fifty years.

All of this is a long way of saying that men do not think twice in saying, and they’ve all started podcasts to say, that “Public schools should be ended,” “We don’t need schools,” or, my favorite, “Schools are brainwashing camps.” Hey, teacher, leave those kids alone! How men of mature years say such things without reddening at the stupidity of such statements is a testimony to what the media, even—perhaps especially—the conservative media, does to one’s thinking process. Fifty years ago, the likes of John Holt, Raymond Moore, Ivan Illich, and other early pedagogical pioneers made like statements, but they did so from a place of erudition and nuance. It is we, their unlettered grandchildren, who rehash their ideas sans the mountain of meaning they assumed.

As I have often written, the problem with the rainbow of religious and secular conservativisms is that they have no grasp of solving their problems. They spend so much time talking about how they want things to be that their comprehension of things as they are is retarded. Thus the conserved have a fair knowledge of what’s amiss with industrial learning but they have no ability of how to solve these problems, problems which they assert do great harm to souls. Perplexed, they self-contentedly stall out at, “I only have to worry about my family.” What traitors. To conservatism? No, to mankind. To see an evil and not move might and main to right it is cowardice. If one sees a social problem, and they merely respond to it personally, this is effeminate. Prophet Ezekiel said to these epigones of Burke, “When I say unto the wicked, Thou shalt surely die; and thou givest him not warning, nor speakest to warn the wicked from his wicked way, to save his life; the same wicked man shall die in his iniquity; but his blood will I require at thine hand” (Ez. 3:18).

So Here We Are

Into this cooling of public sentiment towards formal education came the COVID shutdowns and what is called Artificial Intelligence. As in many areas of life, these developments sped up processes already in motion. Casualizing trends of life were furthered. If education is simply the individual accrual of data, why not watch an appointed number of pre-recorded classes until the sufficient number of boxes are checked? Added to this is the demographic reality. Babies were not born 12 years ago during the Bush-Obama depression, what the Madison Avenue boys still spin as the “Great Recession,” babies who would just now be entering college. This has caused despair for private schools, who must shift for themselves, and glee for municipalities ever eager to trim the budget.

So here we are. Schools are challenged to explain why they exist. We ought to embrace this challenge.

Whatever the level schools ought to begin at the beginning, we ought to encourage rootedness. Only from this stability can we as educationalists and as citizens address those above-mentioned foul fruits of unrootedness, and only from this can we strike a blow against predatory political, economic, and social combinations.

For twenty years I have seen men appraise what we broadly call the New World Order only to stall out in their attempt to push back. We must start with rootedness in our lives, in our children’s lives, and in those communities which ripple out from that. The environment of formal education is the ideal place to do this, and the Divine Office is the ideal framing of a school day.

Filling The Void

The godlessness of a child’s day is the greatest strike against modern education. Note that I did not say “god-againsted-ness,” but god-less-ness. It is worse to be blasé of the divine than to be hostile. The opposite of love is not hate; the opposite of love is indifference. Before the carousel of errors which attend modern education, the absence of God is the greatest strike. It is the void of what should be there, like a missing limb or an empty seat so lately occupied by a departed. It is a crime that a young one not be told who made them and why they are on this earth. It is this void of meaning which chiefly explains the ever-rising percentage of teens who go mad.

You see, though, it is not enough to establish the fact of a student’s Creator, this must be often and commonly acknowledged. The school day is a liturgy of a sort, it certainly is ritualistic. The warm presence of God ought to assert itself in the educational rhythm just as formally and regularly as the schedule of instruction. Ergo, the Office.

Rhythm

The holy Office grounds us in time as the holy Mass does in space. This is to say, the Divine Liturgy accents the physicality of Christianity while the Office highlights our temporal rootedness. In both instances the holy Liturgy insists that religion is not an amalgam of beliefs one ascribes to. This error of definition is the result of the one-two punch of the Reformation and Enlightenment. By assembling for the Prayer in groups at the regular times we are reminded that the Kingdom Of God is already on this earth, that Christian life is a social reality not a me-and-Jesus duo, and that a soul wherein God dwells is in heaven now.

An Inconvenient Truth

Religion ought to have a certain inconvenience to it; its very imposition asserts its importance. You may remember that nugget the next time a Day of Devotion—what is now flatly named an Holy Day of Obligation—rolls around. Yes, the point of religion is to be inconvenient, to impose itself upon the mundane.

Let us recall the old apologetic for Abraham’s sacrifice of Issac: What one will not sacrifice automatically becomes one’s god. If something, someone, or some habit stands in the way of God, that thing in se is one’s deity. Congratulations Liquor, Anger, and Sloth, you’ve been promoted! But once God busts those fellas down to size one gets God back and not some idol. The clock can be an idol as soon as anything else. Musha, in a school the clock is more liable to be an idol than anywhere outside of a stock exchange, a racetrack, or a prison. That the Prayer interrupts a school day reminds both pedagogues and learners that there is a divine order greater than our daily concerns.

While this dynamic is true for genuinely sinful things it also holds that legitimate pleasures, persons, and habits may be sacrificed to stay in good form. The sacrifice of time, of my precious personal schedule, is just as fitting a way for the inconvenience of God to assert himself as in my diet (fasting) and sleep (vigils). St. Paul gave up his persecution (Acts 9), but he also gave up his hair in a vow (Acts 18), one was a sacrifice of his sin, the other was part of an optional vow, both moved him closer to God.

It is the genius of Catholicism to knead into daily life many opportunities to, “offer it up.”

The Office is a medicine to anomie by relentlessly and repeatedly squishing us together time and time again. It is a medicine to meaninglessness by taking our class time and sacrificing some of it to God.

Sacrifice is not a destruction, as Pope Benedict reminds us, “What then does sacrifice consist of? Not in destruction, not in this or that thing, but in the transformation of man. In the fact that he becomes himself conformed to God. He becomes conformed to God when he becomes love. ‘That is why true sacrifice is every work which allows us to unite ourselves to God in a holy fellowship,’ as Augustine puts it.” The Office provides the individual and social groups the opportunity to remember the imposition of the divine so often as he takes the Church up on the Discipline. The Prayer is work, and the manful soul does not shirk from the same. Whether I feel like praying or not, the Discipline reminds me that faith is not a feeling. In fact, the more disinclined I am to pray canonically the more I may learn this lesson.

Generosity

Manys the father has warily contemplated how the generosity of manys his daughter may find itself in the arms of some roguish and unworthy Chad. Yet behind this so middle class of anxieties is a calm and beautiful observation. Young people are in fact generous by nature. Youth may benefit from the mature mien of the Divine Office precisely in proportion to the delightful excess of sentiment which characterizes that chapter of life.

The other-directed focus of liturgy is a defining characteristic of this highest of prayers. When this is rightly conveyed to young ones their natural generosity of spirit will ignite great attraction towards the Liturgy. Present to students the other-centeredness of the liturgy with the same tone of voice as one speaks of the Peace Corp, Teach For America, military service, and environmental protection and you will see them rise to the occasion.

We have seen the popularization of “service hours” as part of both grade and tertiary education in these states United. On the one hand it is laudable students be led to understand education is not the isolated accumulation of knowledge and successful completion of hoops jumped; on the other this codification is a sure sign of social decomposition. The moment virtue can only be furthered by institutionalization is the moment that virtue has died in a people. Ask Augustus if his sumptuary and fertility laws revived the Arcadian manliness of the early Republic. Forsooth, if authority must impose on students artificial charity via service hours this is a greater commentary on the sour parental souls which reared such lead-eyed children. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Join students at the generous prayer for the world which is the Liturgy Of The Hours and you will prime the pump for civic generosity in later life, Chads notwithstanding.

The Office in schools is advisable because it trains the student to a regime of prayers offered chiefly for others, not himself. The Discipline breaks the consumerist attitude which does such damage at present in the religious and academic spheres. It is a sacrificial work of charity where the young pray-er learns quickly he is not the star of the show.

Community

The Discipline roots us in our neighborhood. Another poverty of Modernity which the Divine Office enriches is community. Over the last decade every Freemason town council from coast to coast has slapped “community” on their letterheads and welcome signs. Like “fresh” food and “democratic” government, it may be the use of the word expresses the desires for the thing more than the thing itself contains, but it’s a start.

The Divine Office forms community. It ought always be done in a group, and preference must be given to this aspect of the prayer over every other. Community before everything with it comes to the Office. Here we see once again how the Prayer checks our own eccentricities. It happens that when I say the Prayer myself I do tick off many liturgical boxes I do not when I go to my local parish. When I’m by myself I strike off, “Ad Orientem,” “Latin,” “posture,” and “chant.” Yes, in some ways my private performance of the ritual is in tighter conformity with the history and mind of the Church than it is at the church down the street, but those ways, alas, are Orthodox and protestant (sic) ways.

This is to say that Catholicism is the only Christian group which is realistic; Catholicism is the only group to say that the Church is a present reality, not a fetish of the First Century or the First Millenium. “Realistic” and “reality” come from the Latin word “res,” physical thing. Catholicism is the church par excellence which believes the Church is a social reality now, one may join its ceremonies now, pray with its adherents now, and phone up its ministers now. Most importantly, the Church Of Rome is the only church which at once umpires Christian heritage while adamantly refusing to become a slave of the past or of the present. It is the only church to see the Holy Spirit’s role in history in the eternal now, to see it in kairos time. It is on this point one must always prefer common celebration of the Hours over private.

At manys the church I’ve joined in at the Office there has rarely been a consciousness of orientation, sacred language, physicality, or musical quality. In fact, in the best bare bones American liturgical tradition, I am certain that the people at the local parishes I join at the Office haven’t the slightest idea that the normative setting of the Office is recto tono chant to say nothing of the other niceties. Theirs is a celebration as banal as we’ve come to expect from all suburban religion. The people there are befuddled by even minor calendric variations, even if those variations have been encountered hundreds of times before. These dear souls are like the forgetful Dory in Finding Nemo. I sometimes wonder how they operated a vehicle competently enough to get to the building. Nevertheless the communal dimension of the prayer outweighs all other considerations, and their common banality outweighs whatever traditional elements I may personally bring to the ritual.

This supremacy doubly wars against individuality, it wars against the inherent protestant tendency Americans are drawn to as a feature of our national character, and it wars against the individuality consumerism is eager to stoke in men. It’s all the easier to sells tchotchkes to isolated and lonely people than those who know they are cells in something great, be it a family, country, or church. When one is unrooted, your capitalist moneyman is the least of your problems. If one is isolated, he is prey to all sorts of personal and political tyrannies. If you think it is rough falling into the hands of the living God, you should try the embrace of a dead god. Isolate men and watch the attorney, the drug man, and the usurer come into their own… on your neck. Isolate men and you will learn what real chains are. But welcome school children into a living community in conversation with the living God, and all liturgy is conversation, and those ones will grow up and put to flight those pimps. One appreciates the common Office as one matures, and a chronic solo prayer when community participation is possible must be scorned as the fruit of a juvenile soul.

As Fr. Charles Miller writes in his handy commentary Making The Day Holy, “It is true that bishops and major religious superiors have the authority to commute the Office to some other form of prayer [for those under vows]. Such commutation may be justified in individual cases and for a period of time, but the arrangement and content of the Office allow for and even occasion a spiritual development and maturity which cannot be found elsewhere.” Vows or no’, the liturgy teaches the participant maturity.

The Office’s job is to cramp my style and yours. It’s easier to stay home and pray by myself. When online celebration of the liturgy came in vogue during the COVID days, it was easier not to boot up the computer. While the ease of saying the Office increased, I still was making excuses. What the Liturgy was inviting me to was to reach outside of myself into community.

What makes the Office especially appropriate to schools is the existing congregation of learners. In a sense the Office in schools sacramentalizes the academic community. This is nothing more than what all liturgy ought to do, take the work-a-day and point it, if only from time to time, towards God. This is true for sacramental ceremonies and the Divine Office all the way down to the objects of the Rituale, be it a blessing for a mug of beer, a motorcycle, or a puppy dog.

How often does the student ask quietly and out loud, why are we doing this? It is often an unsatisfactory or absent response from a teacher which triggers a life of intellectual apathy. If one’s teachers were not able to pitch a life of the mind, the student sensibly concludes, it probably isn’t worthwhile. The Office allows all those involved in an educational setting, instructors, students, and—my enemies until I had to become one—administrators—to take our time in school and in a concrete, ritualized fashion offer it in a meaningful way to God, the ground of meaning.

Finally, the regular celebration of the Hours breaks the isolation which the modern top-down classroom nurtures, and which the COVID days exacerbated. Surely, I cannot be the only man who has noticed the rise of people averting their gaze in daily interactions. Lowering eyes were once the province of the young child and the cutpurse. What does it say that a nation’s people comport themselves as such? Externals show internals, and you know as soon as I the feeble spirit which shifty eyes announce.

At Apocatastasis we smash shyness by lassoing all, including the reticent, into the ceremony. We do this by developing a schedule of who will be cantor and hebdomadarian from day to day; these roles throw the shy student into a role of leadership. In a low-stakes setting it breaks the shyness of our time. By inches student participation at the Divine Office builds confidence in the young learner, confidence being the necessary footing of an agentic life in years to come. Rear a generation weaned on agency and watch the tyrants run like rabbits.

A Gentle Reminder

It is the hour of the times that just as the nature of Postmodernity is making itself known, that the last fumes of Christianity are wafting off from the West. The Baby Boomers were hardly evangelized, but they had enough of the old-time religion to keep up some Christian habits. If they wouldn’t go to church each week, they’d at least go quarterly or annually; if their tongue wasn’t squeaky clean, they at least didn’t want cussing on television; if their personal creed likely had all sorts of heresies imbibed from pop culture, they at least put their child in CCD. Those Boomers have now aged out of active society. But as lukewarm as that generation was, they acted as a dam against nasty social developments. Should you wonder why one sees a quickening of unchristian social trends, know it is because that lamely Christian generation are going to their fathers. What is worse than lame faith? No faith. Lame religion at least is a start. Go ask Apollos if he had an easier time working with people who knew of the Holy Spirit or with those who didn’t (Acts 19). One has a better chance reaching people with a distant, sentimental memory of God than people who’ve no foundation a’tall.

Ecumenism

The Great Speckled Bird is looking a bit rough. If we see a paganization of society, what purports to be Christianity itself has seen better days. The mainline protestant denominations have gone the way of all flesh. The old-time protestants who have successfully maintained the “mere Christianity” of the Reformation, those who have not been swept into the Church Of What’s Happening Now, are shattering into a hundred (more) ham-fisted sects in response to the stresses of Postmodernity.

If the secular conservative who baldly asserts, “We don’t need no education,” is incapable of seizing the authority in society—the actual authority, what we might call gravitas—worse by far is Pastor Billy’s Bible Church. The protestants are good men, and they’re Christian men, and they’re holy, but the Radical Reformation protestantism which defines American religion is hopelessly shattered. Unmoored from tradition, canon law, hierarchy, and the example of the saints, American low down, hoedown Christianity is more apt to speed up secularism as anything else. Who can blame men scandalized by these sectarians when they conclude that the husks of the World are more tolerable than the fads and eccentricities of the Saved.

Protestantism can do fughall in the face of an organizationally unified New World Order and the secularism which philosophically undergirds it. In fact, I make bold to say the abysmal failure of conservatism, particularly religious conservatism, to conserve anything stems from the absence of a liturgical consciousness. Until they put on this mind they will continue riding around as so many Lone Rangers. Then again, there’s a strange thrill many of the conserved get fancying they’re the last of the Mohicans. Anyone up for an hotel room Latin Mass or Gab group?

Mind you, all is not well in Catholicville. Near as I can tell, the Roman Catholic faithful are split on the one hand between normies who have no understanding of present dechristianization, and on the other hand, nervous Savonarola types who’ve made totems of the past, and the neither of them has the slightest interest or energy for evangelization. Sure, life gets you coming and going.

The Church Reaches Out

As we labor in the classroom to form an intelligent and agentic generation we see the Divine Office extending two arms, one to the lost World and one to a shattered and anemic Church.

Towards the Postmodern world it offers beauty. Things are far too far gone to make rational appeals to men. A wallop upside the head by beauty is the surest way to attract the lost. As Dostoevsky’s Idiot says, “Beauty will save the world.” Of course, rational appeals can be beautiful, but for a society given to images it is the physical which is fetching.

It is on this account care ought to be shown towards the chant tradition and posture, even in humble, mundane, and yes—grouch as I might—in individual celebration. While clerics are too easy to dismiss liturgical complexity on pastoral grounds, perhaps those with the care of souls have their finger on a pulse which ought to be heeded. Allahu a’alam. In a school, however, greater attention ought to be given to posture and music in the beautiful drama of the Office and the liturgy in toto. As scholastics we must see ourselves as marking time until general society has the maturity and appreciation of these elements of the liturgy once more.

What people often forget when discussing the simplification of the liturgy in the Twentieth Century is that the educational soil of the masses, which once had been fairly grounded in the Classics, including not just the rudiments of Latin but a familiarity with a canvas of ancient literature and allusions, was so eroded by the 1930s and ‘40s that the ceremonial of the Church necessarily had to change to be intelligible. This was not the fault of clerics but of schoolmen. That the New American Bible, the liturgical version of the scriptures used in Yankeeland, is written for a seventh-grade reading level is proof of how far general education has gone down the tubes. The liturgical simplifications we see are a loving condescension of the Church to the aliteracy of the modern man. Perhaps if enough teachers and students take our vocations seriously, we will raise the sophistication of mankind high enough to forge a people once again capable of enjoying a fuller rituale.

You never know who is watching, nor who might be struck by your diligent performance of the Prayer. In manys the field trip and like outing of Apocatastasis’ we have had occasion to establish the Prayer in public. The students always bring beauty and poise to the workaday bustle. The celebration of the Office is neither preachy, lengthy, nor self-important; three strikes against protestantized America Christianity (and I include much of Catholicism under this umbrella). Those elements of formal faith which has so turned off the mass of our countrymen are not present in the Liturgy. It is a chaste prayer, deliberately short and to the point in the Western tradition.

Towards those souls baptized into Christ but outside Christ’s Church, the Office poses neither the sacramental nor the sacerdotal difficulties encountered when the topic of ecumenism meets that of the holy Mass. At an hour where, on the one hand, Catholic schools for financial reasons must allow students from diverse faith traditions or none a’tall (and “nones” are the fastest growing religious demographic at present), and at an hour where the general population is more and more seeking alternatives to public education, many are the ecumenical possibilities of the Divine Office. You see, ecumenical celebration of the holy Mass runs aground because the sectarian is necessarily unable to receive communion, whereas the Office allows for full participation of the Catholic, the protestant, and the Orthodox, hell, even of your Druids and your voodoo men, without the climax of the prayer leaving some excluded. The Office may be an ecumenical halfway house between private prayers and that full liturgical participation which must await reception into the Catholic Church to enjoy. The Office is a gentle introduction of liturgical prayer which may in time, please God, invite the worshiper into the fullness of the Church.

At the same time the Hours pointedly assert the grave wound ecumenism means to address and heal: authority. By participating in the liturgy one de facto acknowledges the authority of the magisterial Church. One doesn’t make a de jure submission to the Church of Christ, true, but one at least verbs submission to the hierarchy and all that means, if only in the interest of practicality and order.

It is in the Office celebrated over a lengthy period one can see the Church’s mind on topics brought into contention by sectarians such as the sacraments, the role of Mary, and even the hierarchy itself known not as a statement to be asserted intellectually but as a reality manifested in living contact with the living God. Those doctrines proper to Rome are massaged into the rhythm of prayer in a manner disarming to American protestants so used to polemical disputation.

Patience

The Office teaches patience with myself and with others. It teaches us that the perfect and be the enemy of the good. It does not take long with students new to the Prayer is realize that, “Today things won’t look like Solesmes!” This is good. The halting, the wrong pages and antiphons, the rough pronunciation, all of these are good in learning the beauty of imperfection; they check whatever of the anal retentive we may have.

The imperfection of our celebration is itself a sacramental. Various trends presently combine to make men more apt to sever ties. Regardless of one’s worldview, those others of his mind are more liable to end relationships as they purity spiral off their high horses. This is hardly a leftist or secular trait. The Office teaches us to bear with each others’ superfluities in patience.

Liberality

It also instructs us in liberality. There was a time, and more than a passing phase, when I was personally quite strict with the easterly direction of prayer, chant, posture, and the like. The high point of this energy was when I said Terce on and in a MetroNorth train bathroom.

As I’ve gotten older, I turned into a terrible liberal. While I still keep up with the whole cursus of the Liturgia Horarum, I only mind the above trappings twice a day. The other hours are apportioned between online groups and pacing recitation; I’ve even taken to combining hours, using the Angelus as a palate cleanser between one prayer and another. Ah, musha, if I keep up like this, I’ll be a grunting Hottentot in no time!

In later years I’ve worked in a balance between the present books and prior editions of the Office. In doing so I’ve come across the subtleties different rites and orders have developed in their prayer. An especially happy invention and subsequent addition to my celebration has been the reading of monastic rules as part of the morning cursus. This develops of width of vision when it comes to life which nothing else can offer. The diversity of the Divine Office undermines the “my way or the highway” mien which affects both modern religious life, and—as politics serves the role of religion for many skins—differences of worldview.

A maturity develops in all of these. As one learns of the vastness of the liturgical tradition in one’s rite and in the Church at large it becomes obvious that one cannot reasonably do each facet of the Office each day and still see to their duty of state. In fact, the tradition is so grand that a monastic could not do as much. In response to this one, learns moderation, one learns that the liturgy is an organ which pulses on beyond oneself. Rather than being a watering down, this necessary moderation teaches one they are a living cell, part of a larger whole.

Applied Education

As a teacher of the humanities, the Prayer drives home points taught in class which only repetitious ceremonies can develop over months, years, and decades. Because of the nature of industrial education, a model which has largely been adopted into homeschooling, it happens that students come to the Institute with a nigh on impossible ability to imagine different sciences connected one to another. Because of the way disciplines are broken up, the learner’s mental muscle of seeing life in a united whole is atrophied.

The Liturgy Of The Hours is a corrective to this handicap. The hymns, antiphons, Psalms, lessons, and collects were written at widely different times, yet they speak of a united reality. It is a literary museum of sorts, with the different elements a pastiche of various cultures and personalities. The Office teaches not only a liturgical tradition, but it trains the mind to grasp what academic traditions are.

Rebuilding

The Office is nothing more than the spiritual radio station of the Church. What an honor for schools to participate in educating a people fit to tune into this station. Yes, it is true that vernacular liturgy is permissible at present, and doubly yes, it is true that vernacular celebration is the expressed policy of the American episcopate. This is a sign not of liberalism or watering anything down; vernacular celebration is a pastoral allowance in the face of the population’s receding education. As hours in class increase, and more and more men sport advanced degrees, it seems the actual general education declines.

While acknowledging pastoral necessity—it may be the population is too dull to appreciate things like chant, for example—it is the charge of schoolmen to not just meet present needs but to make provision for a future society better educated. When that time comes what laurels teachers will have for having formed men capable of joining in the Church’s rich caeremoniale with all of its august trappings. Yes, it is as clear as clear can be the Church does not care about its liturgical heritage. Let us mark time until it does once more.

The Big Picture

Never have I ever blushed in saying that the fundamental telos of Apocatastasis Institute has been to form a people capable of personal, economic, political, and cultural self-defense. Indeed, the role of all right schools is to form such a people, men capable of asserting their rights against bullies and pimps. Forsooth, the Lord above only game man a body so that he may throw it against evil.

Here at home, it is certain that the tyranny which is building in one corner, and the liberty which men are nurturing in another, will meet in a fight. These two energetic lines will have it out in physical force. It is the solemn duty of all right education to form men mentally, spiritually, and socially capable for this exertion. Unlike what the goofy conservatives and truth community hold, that this row will happen when The Cathedral pushes too many people too far, this fight to the knife will not be won by free mankind for some generations out, not in this part of the world at least. Those who think they have a bead on events are bugged the hell out on The Patriot and Rambo films; the conservatives speak like little boys watching Westerns.

Hayya ‘Ala-l-falah

It is a point of record that the most muscular and competent response to the New World Order has been from the Ummah of Mohammed. If my above assertion about schools and self-defense is correct, then it behooves us to observe the role which canonical prayer played in forming a homogeneous Islamic population capable of the discipline of physical exertion. The point, and it is a point best learned early, is that spiritual liberation precedes physical efforts at the same. That is what the Muslims’ manly striving teaches us.

There will be a fight, forsooth, but it will not be in our time if it’s to be successful. It is for schoolmen to prepare a people fit for a national liberation struggle which is generations distant. Before men can responsibly assert themselves in arms, for a physical force struggle is the highest test of a community’s coherence and competence, there must be a spiritual, mental, and interpersonal revival.

I do not say it is given to us to arrange what must be, I do not say it is for us to advocate for it, I do not even say that when the time ripens to bring the tyrants to heel that it will be advisable to engage in a fight. I say that what goes for individuals goes for societies, that vigilance is the price of security, and that complete men capable of spiritual, mental, and physical self-defense can check criminals when they come looking for trouble. It is for schools to form such a pacific but prepared people.

Of all the lessons learned in school, the daily Office teaches a master class in the lessons of dedication, piety, patience, and comity, those things which prevent physical striving for liberty from becoming seven times more unjust than what preceded it. The errors of Islam notwithstanding, the discipline which their salah instilled in them was the biggest ingredient in their drubbing of the globalists’ armies.

Remember Baghuz!

Yes, the greatest opposition the confederates of the New World Order have faced in our day was from the Muslims when they trespassed on their lands. I have lost count of the number of amputees of a certain age I have come across hobbling about Connecticut as a grim testimony of this fact.

It is advisable that patriots note how the men of other lands have struggled against the New World Order. In all the times and climes, we may observe, the victory of the Taliban is the greatest triumph of self-determination in our lifetime. Close on the heels of that I adduce the insurgency of the Second Iraq War and elements of the Arab Spring. Now don’t worry, I’ll not be going in for that damn Islam anytime soon, and I am well aware of the fanaticism, insanity, criminality, and infiltration which characterized the Middle Eastern, if not the Central Asian, Islamic response to the New World Order. Still and all, the globalists were dressed down in their attempt to lasso the Dar al-Islam into their banking network. This Western banking scheme explains in a nutshell the last 20 years of the Western and Islamic tussle. Still and all, who is sitting in Kabul?

I followed the saga of the War On Terror closely, I follow it yet. How many stories are there of Muslims praying Salawat in the middle of military operations, sometimes amidst the red rush of battle itself. Who did not stare in awe to see the men of ISIS maintaining to the last their liturgical cursus even as the Kurdish communists set upon them in the football field of Baghuz Fawqani. I care not that Islam is a false religion, nor that ISIS represented the worst of the Muslim people, nor that the group was riven with supergrasses and madmen. What I hold up from that strange group at that desperate hour is the sociological value of canonical prayer as a stiffener against overwhelming odds.

Conclusion

The Divine Office is particularly fitted to a school because it grounds the student’s life and study in meaning, teaches by rote academic lessons which cannot be grasped in a lecture, refines our etiquette, and offers a calm onramp to liturgical prayer to a multiconfessional people.

Being an other-centered-prayer, the Office teaches us piety classically understood, piety as the outlay of energy and attention given for the health of the polis. The Prayer formalizes good citizenship as it calls us in the classroom and neighborhood together again and again and again and reminds us of our Creator and the symphony of salvation of which we are all a part. In so doing, the Divine Office checks the antisocial habits telephonic interaction not only tolerates but encourages. The Prayer is a gentle curative to the schisms of the last 500 years.

Finally, the discipline of the Office nurtures a cornucopia of sentiments and virtues which are prerequisites of any national liberation effort. We may say that the percentage of the community who regularly join in the Prayer will broadly be an indicator of the percentage of men capable of putting bullies in their place. All of this, bully banging as soon as anything else, are lessons best introduced during one’s formative school years. Root a child in his Creator, his community, and in meaning and watch an oak of a man grow.

Well, that’s that, as the girl said to the sailor.

John Coleman co-hosts Christian History & Ideas, and is the founder of Apocatastasis: An Institute for the Humanities, an alternative college and high school in New Milford, Connecticut. Apocatastasis is a school focused on studying the Western humanities in an integrated fashion, while at the same time adjusting to the changing educational field. Information about the college can be found at its website.

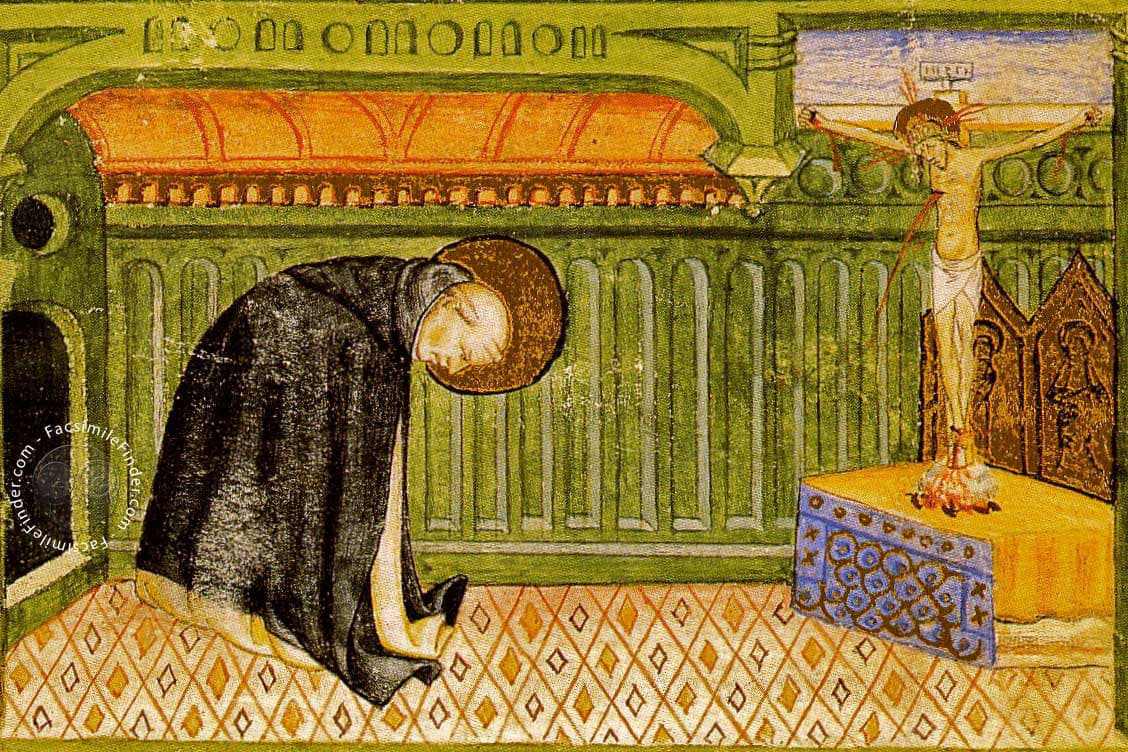

Featured: Modi orandi sancti Domini, ca. 14th-15th centuries.