The unanimous tributes paid to Robert Badinter leave a large part of his work in the dark, and overlook certain flaws in his thinking, certain deleterious effects of his political decisions, the price of which we are cruelly paying today, and certain ideological inconsistencies. We take a critical look at the career of this great figure of the humanist left, and the consequences of his actions.

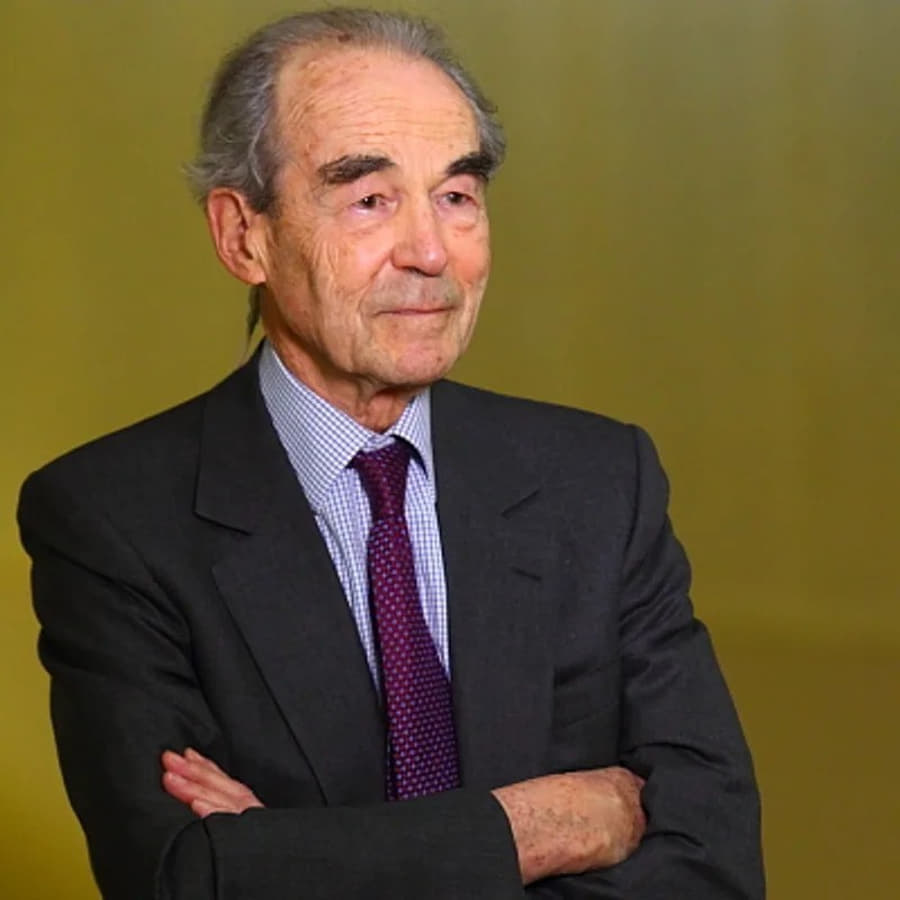

By a natural law of things, without any relief of sentence, without the race to the abyss suffering any special consideration, at the end of his old age turned into a prison, following an irrevocable sentence, tortured for a long time, life has just condemned Robert Badinter to death. After the august Jacques Delors, who had the right to a national tribute at Les Invalides under the great European flag, his imaginary true nation, it is now the turn of the venerable Robert Badinter to pass, without a trace of irony, to head off into the sunset. One by one, the French giants of the early 20th century are departing.

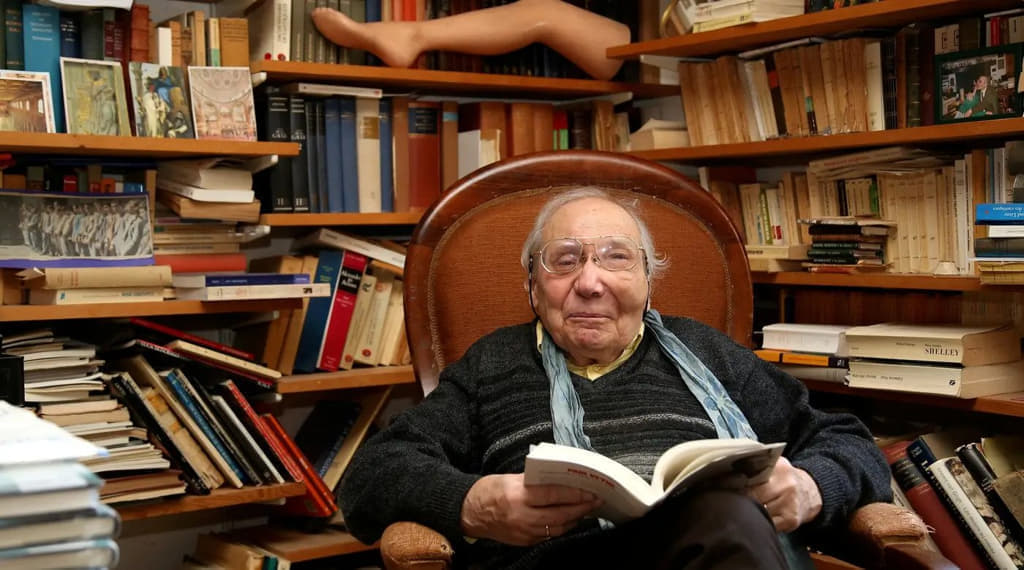

A committed man gifted with charisma and a singular art for the phrase, his intellectual positions and biases, however questionable, do not prevent him from being shown a certain respect, like that owed to one’s adversary, and take on an obstinate and courageous air. Badinter, a life-long struggle, as we like to repeat since his death. This intellectual of the law, professor and academic, Minister of Justice, sage among the sages of the Palais Royal, then Senator, was a leading figure—a figure of the progressive left; a humanist figure; a heroic figure in defense of the oppressed. A totem without taboos. A certain section of the Catholic press praised “this force of law” and “this bulwark against populism,” whose aim was to bring the law fully into the Republic, so that, through the Constitutional Council, respect for fundamental principles would triumph.

Once we have said all that, and given Robert Badinter his due, it is time to return to the many pitfalls of his work and thought. Some have said that he was one of the last men of the Enlightenment. He was, for the better, a disciple of Condorcet in finesse and elegance, in his ideas on liberty and tolerance, in his mathematical sense applied to ideals in the form of constitutional equations. And above all, for the worst, born into a class that had succeeded, through social mobility, in replacing the old ruling class and seizing power, while carrying the new ideas of his time, universalist, generous and tolerant, Monsieur de Badinter was one of the great bourgeoisie of the left, capable of great indignation, lavish in humanism, generous in virtue and abundant by decree, sure of his duty: to impose his ideas on the people as a whole, applying them to reality without worrying about their consequences. This liberal, progressive bourgeoisie, who reaped the benefits of the French Revolution, was always at the forefront, on the correct side, marching with the party of order. It is easy to rant about the plight of criminals from below when you are not looking up to those above; it is easy to make humanist judgments about migrants, welcoming people, the Other, when you have spent your life in four arrondissements of Paris. It is easy to be comfortable in your own office, condoning and condemning with relativism, but it is also easy to have class contempt. There are the enlightened know-it-alls, who have understood; and then there are the others, the lowly folk, inhabited by all manner of wrongs, vices and crimes. Robert Badinter, his eyebrow furrowed, had the arrogant facility to declare that if you were in favor of the death penalty, you were a fascist; that if you were in favor of the obvious regulation of immigration, you were a racist; so many cookie-cutter, self-righteous judgments that never suffer debate.

Robert Badinter was passionate about human rights. What a passion that was! It was this passion that drove him for years to defend the oppressed, the persecuted of every stripe. In the name of human rights! Joseph de Maistre’s gentle irony of knowing the rights of Italians, Frenchmen and Russians, but ignoring those of a bodiless, abstract man, pure concept. Karl Marx spoke of the rights of the bourgeois, which made it possible to lecture others while ignoring the misfortunes of those closer at home. And it is at this very moment that Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s words in Emile make sense: “Beware those cosmopolitans who search far and wide in their books for duties they disdain to fulfill around them. Such a philosopher loves the Tartars, so as to be exempt from loving his neighbors.”

To Bernard Pivot’s question: “What would you like to be reincarnated as?” the wise man replied: “As a fox, because even if he is trapped, he can cut off his own tail to be free.” Ah, freedom! Cherished freedom! The one that Eluard’s poem haunts school classes about! Here too, it is astonishing that Mr. Badinter, shouting his passion for freedom at the top of his voice, had nothing to say about the vaccination pass and the suspension of unvaccinated hospital staff. No outcry, no humanist, left-wing, indignant reflection for poor people who find themselves with nothing from one day to the next. Similarly, when Edouard Balladur’s government sought in 1991 to work, supposedly, against massive and unregulated immigration, it was the Constitutional Council, of which Badinter was president at the time, that rejected the Pasqua bill in the name of France’s humanist and universalist values. The former Ricard executive himself denounced the “dictatorship of judges,” who, depending on circumstances favorable or not to their ideas, use the law and its values to make politics rain or shine.

When the Yellow Vests demonstrated and brandished the President’s head on a pike, in 2020, it was this same defender of freedom who vituperated these good people, finding it odious, almost fascist, that such an effigy should be brandished. But democracy is not all smooth sailing! It cannot be summed up in a conversation on the set of a TV Parliamentary Channel, nor can it be reduced to parliamentary palaver. Violence is a fact of politics, because it is exercised as a perpetual balance of power, and it can be seen in history as resolutely tragic.

Robert Badinter was not a politician. Like Jacques Delors, of the same generation but operating at a different level, he was never an elected official. His career can be summed up by the fact that, in the 1980s, he was the strongman of the judiciary, accompanying the ideas and interests of a new category of decision-makers known as Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (VGE), Jean-Jacques Servan Schreiber, under the leadership of Pierre Mendès-France, an anti-Gaullist and Atlanticist whose involvement and influence on political ideas in the early years of the Fifth Republic is still unmeasured. Badinter, a handsome man with slicked-back hair, an elegant suit and modern, close-cut hair, was a figure of change that was to follow the end of Gaullism, which, it should be remembered, was a national rally for a sovereign France against Europeanist yes-manism and American Atlanticism. The much-vaunted liberation of society, applied on those down below, needed to find figures from above to make it palatable in politics. It found Robert Badinter.

His famous battle was for the abolition of the death penalty. He was the driving force behind this project; he was its face. It would be all too easy to believe that a single man can, by his own will, change things in this way, without there being any underlying trend. The abolition of the death penalty was already on the shelves of the cupboard of the Second Republic; it was already supported by Victor Hugo, it was enacted in other countries in the 19th century, in Portugal or in the Netherlands; it was already in the program of VGE in 1974.

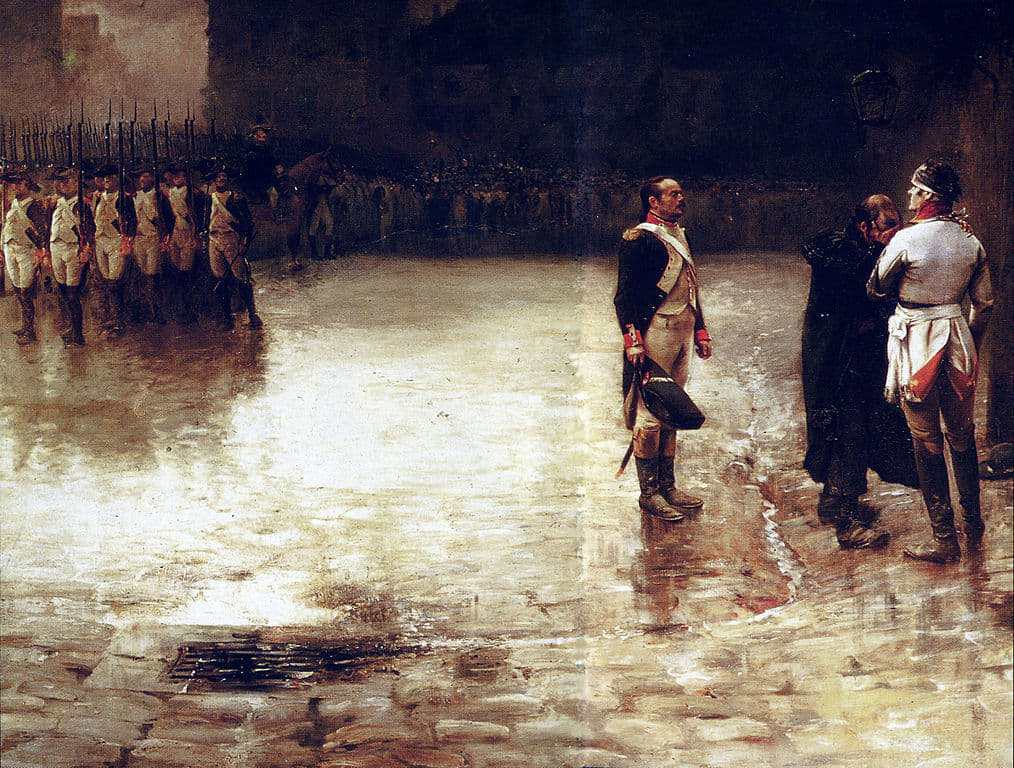

The death penalty is a thorny issue to defend point-by-point and peremptorily. Such a problem does not presuppose a dogmatic solution. It is not that either party is wrong to be for or against it. Robert Badinter was not a man of faith or the law. He started from very precise and fixed ideas, the effects of which must be assessed. We refer you only to Father Raymond-Léopold Bruckberger, Yes to the Death Penalty, which summarizes the conceptual history of the death penalty and debunks the very modern idea that it is a denial of civilization, when in fact it has been practiced within civilization. It was the sacredness of life that justified the death penalty, at least from a traditional point of view: “Thou shalt not kill” was, like incest, a prohibition. Its transgression earned the murderer radical exclusion from the human community, following a public ceremony. This same death penalty in 1981 threatened so few people that it should have been the last measure taken by a left-wing government. It was the first under François Mitterrand.

Opposition to the death penalty remained numerous: religious opposition, which questioned whether a human community could substitute itself for God by taking life, turning the “Thou shalt not kill” principle against itself; conservative and Catholic opposition, which was also logically opposed to abortion. In the face of this “right-wing” opposition, progressive “left-wing” abolitionism advocated its humanist logic of the credit due to every human being, first and foremost a victim of his or her environment. This has led to a kind of lax degeneration of justice, allowing a judge to see a custom in the rape of a woman by a Pakistani migrant.

The first flaw in Robert Badinter’s thinking is that it is permeated by that bourgeois instinct for whom, outside profit, nothing is sacred, neither death nor life, and which makes it criminal to take the life of a despicable murderer, but normal to take it from a future innocent baby—to be both, without the slightest problem, against the death penalty and in favor of abortion. This Left, therefore, good in every way, is in fact a simulacrum of the Left to lyrically conceal the abandonment of concrete progressivism, the kind that was not intended to save the heads of a handful of scum, but to improve the lives of ordinary people. It was at this very moment that a vast abolitionist nebula, meditated in universities in the aftermath of 1968 by agents of French Theory, sought to create a tohu-bohu, a notion dear to Michel Foucauld, in society. Our twisted and tainted elites had to dismantle the totems of our society and break down its taboos. A few years ago, a few renowned intellectuals and committed figures had sought to abolish the age of sexual consent and decriminalize relations with minors under the age of fifteen.

Another pitfall is the assumption that man is infinitely good and infinitely lovable, that it is society that perverts him and that he is unintentionally evil. The death penalty had been applied in a Christian society, based on the Gospel itself. Jesus was on the cross, with two thieves at His side. One mocks Jesus, the other rebukes him: “What is happening to us is just, while he is innocent” and adds, “Jesus, remember me when you are in your kingdom.” This prompts the Lord to say, “Truly, I say to you, you will be the first to enter the kingdom of heaven.” In a few lines, everything is there: a man can be condemned for his crime; by the justice of men, he can be led to die, but he can be saved by divine justice. Traditional Christian society played both sides: God’s justice and man’s justice, earthly life and metaphysical life, body on one side and soul on the other. Our post-Christian society, secularized to the extent that it has digested Christian ideas and done away with them, is witnessing the emergence of a form of justice that gives itself the proper role of executioner and priest. This kind of justice condemns while absolving; it punishes while judging a man’s redemption. In his 1981 speech to Parliament, Abbé Badinter, dare we say it, explained that “however terrible, however odious their acts, there are no men on this earth whose guilt is total and which one must always totally despair about.” This secularized mercy, this unshakeable faith in redemption, forgiveness, conversion to virtue and goodness, sometimes contributes to an obscene fascination that made Fourniret, Bodin or Dutroux famous, and sometimes to an unhealthy victimization that makes the executioner as much a victim as his own victim. Forgiving an executioner is a personal process, and that of little Philippe Bertrand’s mother commands respect, but it is not up to justice to show mercy and have feelings. In short, Patrick Henry is a kind of Saint Blandine, a martyr of the arena? Is it not dishonest to equate an innocent with a scoundrel?

Badinter made a major intellectual error: he confused philosophy with justice. They are two different categories. A man is not guilty, yes, as a concept. When we put a man on trial, we do so in the context of his crime, in relation to the law, and not on the basis of a concept. This philosophy is accompanied by a rhetorical art of clichés, peremptory elucidations, evasions and slips, ideas asserted with authority, false truths and true political ideas, adulterated concepts mixed with pathos and lyricism—which has raised almost no criticism.

The death penalty is capital punishment, because it is at the top of the pyramid of punishments. It is the basis for all possible sanctions in response to crimes or misdeeds. The abolition of capital punishment has shaken the pyramid of penalties and sanctions to the point of disordering the whole, and leading to a tohu-bohu in society where, to caricature, as Jean Ferrat sang in “Tout Berzingue” [“Full-Throttle”]: “steal an apple and you’re done for, shoot a man, you get probation.” All these arguments—”the death penalty is not a deterrent,” “it doesn’t make people think,” “it adds blood on top of blood”—have their share of truth, if only the debate did not stop there. If we believe that justice is reparation by equivalence, then it is only natural that when an innocent person is murdered, justice should give itself a monopoly on legitimate vengeance, to prevent all hatred and personal vengeance, to make reparation for a crime and balance the loss of a life against a criminal whose imprisonment would ensure him, at times, certain moments of happiness—when he has taken a life. And besides, is there not a worse failure of justice and Mr. Badinter’s lofty ideals when a rehabilitated criminal relapses into crime, when a murderer takes another life, shatters a family that will never recover, when prison no longer terrifies the bad souls it houses? It is enough to make one despair of the naivety that fails to see that man is on the slippery slope to evil. Mr. Badinter’s justice system has caused suffering and harm to the people; society has been traumatized by cases, victimized by insecurity, demoralized by injustice, disgusted by the failure of justice. This naïve and generous ideal allowed furious, ideological magistrates to give free rein to their whims, and degenerate intellectuals to spend their pity on criminals. The death penalty had its aesthetics in Montherlant, de Maistre and Baudelaire; the scoundrel became an idol of the counter-culture; the underworld theater of those years had its Cid with Roberto Succo.

“The system is simple: we have a justice of freedom.” In his almost five years as minister, Robert Badinter profoundly transformed the justice system: he abolished the State Security Court, put an end to the “Security and Freedom” text, reformed the Napoleonic penal code; he worked to reintegrate criminals, abolished the high-security wings, while conforming to European law. At the end of his life, he came to believe that prison was torture. Man as a concept is not guilty, and if we like to think that freedom defines man, then we cannot lock him up, either. Man’s inseparability is replaced by his “inclosability.” Let’s abolish prisons! What a program!

“Of all the trials a lawyer can go through, we had forty-five minutes to save a man’s life, that’s the most frightening vertigo a human being can have.” Fair enough. But why, then, did he never write a line, never dwell on the fate—just or unjust, that is not the question—about Bastien-Thiry, Degueldre and Claude Piegt? Jean Dutourd, the bête noire of the German-Pratin world, had the beginnings of an answer: the death penalty should never be abolished for political enemies. The same Badinter, when asked if he would have voted for the death of the king, replied that “the king’s head had to fall for the people to be sovereign.” There you have it. If there is one more inconsistency to be found in his body of work, we have found it.

Nicolas Kinosky is at the Centres des Analyses des Rhétoriques Religieuses de l’Antiquité and teaches Latin. This articles appears through the very kind courtesy La Nef.