Paul Veyne (1930-2022) passed away on September 29. Honorary professor at the Collège de France, he was one of our most knowledgeable scholars of ancient Rome. A tribute.

“Dear colleague, I have read your letter. You are right, the state of Latin is getting worse and worse.” Ten years ago, when I was entering the first year of my studies, I received, by way of reply, this letter from Paul Veyne, so touching, so personal and so pleasant. Imagine the effect it had on a young greenhorn lad who was destined for literature. Imagine today my emotions at the announcement of the death of this professor, and myself, still as green as ever, now a Latin teacher.

“Am I going to follow in the footsteps of my elders? Yes, but I allow myself to choose my own path,” recalled Seneca in a letter to Lucilius. Veyne shared very different ideas from mine. Some would perhaps regard them bitterly. Veyne was a man of the left; rather relativistic, it is true; neither patriotic nor anti-patriotic; a Communist in his youth; a Gaullist in 1969; then a liberal and progressive. He had very early broken with Catholic practice, which he judged to be ancient folklore, and remained suffused with the memory of the war, the collaboration, and the anti-Semitism that he pinned on the old France of his parents. Paul Veyne did not accept any absolutes. “Nihil amirari“: everything passes away: human rights, ideas, Christianity, the Roman Empire and the American Empire. Everything passes away, yes, but everything makes sense in the course of history where nothing is lost, nothing is created but everything is transformed.

For all that Paul Veyne was an atypical gentleman, who has written a classic on the history of Rome. While I was talking to him with admiration about his work, he raised his arms heavenward, cursing his fate: “What I have written is particularly bad, confused and really only slog-work. I have no work. What I have written will be replaced in fifty years by others and will be unusable.” When you read his books from a long and general view, you realize with interest that they oscillate between a clear lesson and a light and exquisite exposé—unlike at times his unreadable peers, whose books are heavy as elephants, tangled in jargon, twisted like Lacan’s language.

There are so many Marmorean figures of Latin letters in France and yet Veyne easily stands out among them. Men such as Pierre Boyancé, Pierre Grimal or Jérôme Carcopino who was a minister under Vichy and the writer of a life of Julius Caesar which is still a milestone. All this has the odor of good black ink in school notebooks. The tireless music of rosa, rosae always sends us back to the same bed of roses. Grimal touched ancient Rome with white gloves. As for Paul Veyne, he was part of the serious avant-garde.

Belles-lettres shook precisely when historians, at the beginning of the 1950s, coming from the Annales school, wanted to take a complex look at history. They no longer sought to produce books that went date-by-date, event-by-event, and by conventional biographies. They found refuge under the aegis of Fernand Braudel who, in The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, expounded his ideas: the layering of temporalities, the longue durée, or even material civilization as prisms through which the historian observes the world and goes far beyond traditional history by opening up to sciences such as geography, economics, ethnology, sociology, or archaeology.

Paul Veyne had his sight on all Latin literature, from Appius Claudius Caecus to Boethius, including also the inscriptions and epitaphs of Romanity, for which he combed the manuals and syllogi of the great libraries. Such certainly was the master’s background and backroom work for half a century. This was also the influence of the archivism of ideas that the obscure and marginal Michel Foucauld defended as intangible proof of the real and the concrete. But before going over to Harald Fuchs, Veyne attended sociology classes at the Collège de France taught by Raymond Aron and applied the theories of the humanities and economics, oriented towards liberalism, from Simmel to Schumpeter, to Roman society, at a time when the class struggle was foolishly plastered onto history by the passive Trostko-Maoist bourgeoisie.

Veyne had a talent for unfolding phenomena, trying methodically, with a strong lucidity close to skepticism, to understand appearances, types, behaviors in Roman society. This rigorous observation went hand-in-hand with a keen sense of historical narrative. In Comment on écrit l’histoire (How We Write History), Veyne did not consider his discipline as a raw and crude science but as “a true novel.” A novel exposes reality, takes refuge in Danton’s phrase in The Red and the Black, “the truth, the bitter truth,” and, at the same time, hits you in the gut, touches you, makes you sensitive, agitates you, fascinates you. In his writing, so many such comparisons and analogies have been carried out with seriousness and accuracy while denoting much originality.

Veyne did not try to tell us that the Romans were superior to us, exotic or grandiose. He did not sigh with ecstasy at the mere name of Rome. He demythologized and even demystified the Romans, placing them in the spotlight. He stopped admiring them, and instead wanted to understand them. Roman society was its own organism, had its own special functioning, its principles, its totems and its taboos. The role of the historian is to deconstruct the strata of society. At the term “deconstruct,” one might gladly take out his magnum 44, ready to do some serious damage. But it is best to put it away, and out this term to use in the same way that Lévi-Strauss did— by understanding that it is not a question of deconstructing our own society but to undertake a disassembling of an ancient society, to disentangle what is complexus-entangled—in order to understand its mechanics; to detach the cogs of the machine, and to observe (as one would take out an organ from a body) the specific purpose of this ancient society.

In Bread and Circuses (1976), Veyne brought out the little-known and crucial role of the euergetes in that complex mechanism present in Roman society. The euergetes was the notable par excellence who, in his city, financed the games, the theater, the baths, with a view to social cohesion—a symbol of Romanity in the face of the barbarians: “imagine a city where the big bourgeois in the corner finances the cinema, the theater, the casino and offers you an aperitif as a bonus, and well, that’s how Roman cities functioned.” One must read the articles in L’empire gréco-romain (The Greco-Roman Empire) [2005] to understand the full complexity of the ancients in relation to their tastes, religion, the idea of faith, entertainment, economics and social class differences. Veyne enlightened us on the status of the gladiator, on the intellectual preoccupations of an intelligent pagan like Plutarch, the splendor of Palmyra, the morality of the couple in the second century even before the advent of Christianity, the existence of a middle class in Rome, between the great families and the plebs sordida. The chapter on Trimalchio in Roman Society (1991) is a true painting of the parvenu, embodied by the degenerate nouveau riche of Petronius’ The Satyricon, who rises by cunning, gets rich by speculating on land, and shows off his flashy wealth.

Veyne was interested in literature. We owe him some splendid pages full of pragmatism on Seneca. We owe him the L’Elégie érotique romaine (Roman Erotic Elegy) [1983], a book in which he explains that ancient poets, such as Tibullus, Catullus, Propertius, are not romantics before the term was invented, or even beatniks, but poets who only seek to play with the codes and conventions of their society, formulating love stories invented from scratch. In the last years of his life, a translation of Virgil’s Aeneid crowned a remarkable work in which one can savor the Swan of Mantua as one would listen to Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony. A freshness of air, a gracefulness, a precious accuracy that buries the unhealthy translation of Jacques Perret of the Belles-lettres.

It will certainly become necessary to write a beautiful book on the life of Paul Veyne. Of all the men I have known, Veyne was the gentlest, the most generous. Not a word against any other. Treat others as equals and call the woman you love with “vouvoie.” Veyne was concerned with the little people until the end of his old age. A local celebrity in Bédoin, at the foot of Mont Ventoux, not far from the friendly monks of Le Barroux, he was among his own people. He was not imperious in any way, always very polite, replying with, “Thank you, master” to anyone who called him by the same title. He did not play the role of the wise old man, scowling and lecturing, and never quick to play the role of the intellectual for women readers on holidays. He always shirked merits and honors without ever refusing them. There was a great humility to the man.

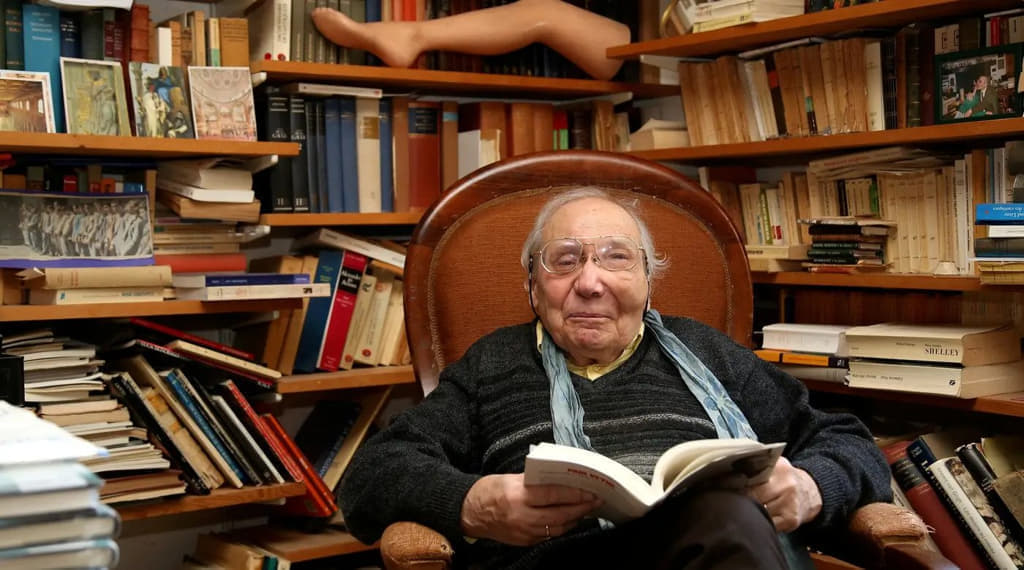

What impressions do I have of him? I see him offering his housekeeper champagne to congratulate her on an ethereal dessert. I still see him offering a glass of whisky to his dog, Clover; making the sign of the cross while talking about General Leclerc; driving a two-wheeler at night while reciting Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” in the original. I still admire him telling me, at eighty-seven years old, the “Voyage to Cythera” at the dinner table, the living room caught in the sunset like a beetle in amber, with a glass of red wine resting on his cheek: “What is this sad and black island? It is Cythera, we are told, a country famous in songs, a banal Eldorado for all old bachelors. Look at it. It is a miserable land after all…” I always imagine him in his office, a great clutter, manuscripts on the floor; on the shelves, broken-backed books, volumes of poems, and a parade of trinkets that ranged from a postcard of Santa Maria Maggiore to a plastic woman’s leg that lay in front of Augustine and Cyprian of Carthage, a Mongolian knife and a photograph of his late son.

Veyne was a friend of Michel Piccoli, whom he met during a conference in Tunis. The actor knocked on the door of his room, the professor opened: “Mr. Veyne, excuse me. You know, I did not study. I am a little ashamed to appear next to you.” And Veyne replied: “You know, you create; through your performance, you participate in works. I do not create anything. I am unable to. I try to understand what guys more or less like you have done in a distant era. I have no merit.”

The master of Bédoin was a lover. When he received the Femina prize for his memoirs, I congratulated him, saying. “I imagine that you don’t care.” And he replied, “Of course I don’t care, but it pleases my wife, and if it pleases her, then it pleases me too.” That was pure Veyne. There was in this small, cramped, hunchbacked man, a sensual temperament. “Since you write love poems,” he wrote to me, “we can be on familiar terms.” He loved women, he who was ugly as a louse, because of a facial deformity. He loved the arts, the poetry of René Char who sometimes succumbed to an ecstasy on the telephone and sometimes to a tantrum; the paintings of Pignon-Ernst and Paul Jenkins, his contemporaries. He loved Italy, Stendhal and Da Ponte’s Don Giovanni, which he could recite by heart, and all the art of which Italy is capable—Giotto in Assisi, the Basilica of San Zeno in Verona, the Parmigianino Madonna of the Long Neck, Piero della Francesca and his Flagellation, Jupiter and Io by Correggio, the Seven Works of Mercy by Caravaggio in Naples.

Paul Veyne was not like other academics, who are often full of vinegar and proud. He was not prim and proper. He had this crazy side that made him eccentric and unpredictable, always ready to play a prank, a dare, a joke. At the University of Aix, he used to hang out on the tenth floor of the building during breaks, to prepare for his passion—mountaineering. He knew the summits of Europe, felt the vertigo of the crevasse, the shortness of breath of the altitude, the illusion of the snow and the perfume of the ice. He knew also the summits of his institution, the Collège de France, plus all the honors that the Americans, the English, the Italians and even the Turks gave him.

And how Veyne suffered in a stoic silence at seeing the people die around him—his son, who committed suicide, his son-in-law who died of AIDS. His marriages were long agonies, recounted in his memoirs—the abortion by his first wife; the hysteria of a Hellenist, daughter of a specialist in Plutarch; a notable village woman, suffering from dementia and depression, the love of his life; and a last marriage, three years ago, cut short because of the cancer of his wife. Beneath the appearance of a grandfather with a singing accent, kind and gentle, there must have been torments, storms and regrets that in ten years of friendship I was never able to pierce. Perhaps a liver sickened by the libertarian intoxication of post-1968.

My old and faithful friend is now on the other side. One morning, at breakfast, with coffee and foie gras, we talked about eternity. Veyne did not believe in God and was sorry not to believe in Him. He wanted to, but could not. For a long time, he had thought of suicide, as a practical exercise in getting all in a tizzy. But he would end up an old man. Eternity, the passage between the world of the living and a filled nothingness, inhabited or not, titillated his mind. It took courage, then, to cross the great cold without hope, with his eyes on death. May the Lord welcome him into His wide-open arms. Last Thursday, he joined Virgil, Seneca and Damien, his son. He will not be bored.

Nicolas Kinosky is at the Centres des Analyses des Rhétoriques Religieuses de l’Antiquité and teaches Latin. This articles appears through the very kind courtesy La Nef.