In Sophocles’ Antigone, the two main characters, Antigone and Creon, are widely seen as representing the two extreme poles of a plurality of oppositions: mostly between natural law and positive law, or between divine and human law. But there has been no shortage of those who, like Hegel, have seen in them the opposition between a masculine and feminine conception (principle), whereby man (i.e., Creon) “has his substantial and real life in the State, in Science, and the like, and moreover in struggle and travail with the external world and with himself,”, while “pietas, in one of the most sublime expositions concerning it—in the Sophoclean Antigone—is declared above all as the law of the female; that is to say, as the law of subjective sentimental substantiality, of inwardness that does not yet achieve its own perfect realization, as the law of the ancient gods, of the subterranean realm, as the eternal law of which no one can say when it appeared, and which is present in opposition against the manifest law, the law of the State.” Hence, on the one hand, one can glimpse, in these remarks of Hegel, a contrast more than between norms (laws) that between institutions (family and state); on the other hand, and more clearly, that between a “traditional” and customary law and between a “statute” and rational one.”

Many other oppositions are traceable, because they are clearly set forth, in the two characters of the tragedy. In particular, Creon identifies himself with the polis and makes the friend/enemy category (of the polis) the distinctive criterion for the legitimization of the decree prohibiting the burial of Polynices, derogatory-modifying the divine (and customary) law of burying the dead. Hence (at least) both the opposition between the political and the legal (understood in Freund’s sense) and the prevalence and decisiveness of the political, which alone guarantees the salvation of all; and to whose necessity (other opposition), every bond of affection, even between blood relatives, must yield, as must every friendly relationship. Says Creon in entering the scene, “I hold in no account those who esteem a loved one more important than their own country. For I – and let Zeus, who always sees all things, know this – would not know how to keep silent when I saw misfortune instead of salvation moving against the citizens; and I would never make a friend of an enemy of the homeland; for I know that it is our salvation, and that we only procure friends when we keep its course straight. With such principles I will make our city great” . The law promulgated by the ruler must thus be “rational with respect to the purpose,” which is, in the case, the purpose essential to the polis, to safeguard it, including by honoring the good citizens and not the others, the enemies.

Which constitutes another essential difference from the divine law, observed by Antigone, to which obedience is due, not because of the expediency of it but because of the authority that instituted it and the custom of respecting it . Indeed, Creon’s conception vindicates even more the character of the law as a human creation, the result of man’s will and ingenuity, which can violate the divine law, as such immutable, to which Antigone appeals. This appears underscored by the chorus in the first stasymus, which is a song about the excellence of human ingenuity and its ability to overcome the difficulties of nature; however, the chorus reminds us of the human faculty (and limitation) of being able to choose between good and evil, and man “Possessing, beyond hope, the inventiveness of art, which is wisdom, sometimes moves toward evil, sometimes toward good. If the laws of the earth he inserts therein, and justice sworn to the gods, he elevates his country; but without a country is he who through fearfulness joins with evil: let him who acts thus not inhabit my hearth nor think like me.” . The exhortation to insert “the laws of the land” has the clear meaning of having to harmonize human law (and command) with divine (and natural) law in order for the work of edification-and preservation-of the polis to succeed.

Almost all such oppositions point to Creon as the archetype of a “modern” (as opposed to Antigone’s) politics and law: the former because it prevails over all normative constraints (summa in cives ac legibusque soluta potestas); the latter because it is rational, voluntary, statute-full, expedient and derogable in relation to necessity. Such concordance, however, has not, so to speak, done much good to the image of Creon, mostly equated with that of the tyrant. Yet Creon is not tyrant in the sense in which, often, that term is connoted: in fact, Creon’s decisions and goals are not diverted from self-interest, but inspired by that of the homeland (al bonum commune). Already in “Oedipus at Colonus” when he performs the heinous act of kidnapping Antigone to force Oedipus to return to Thebes, he does so because the oracle has guaranteed salvation to whichever of the contenders for the throne of Thebes will have the old king near him. And similar is Creon’s position in Antigone: where, in essence, he places the salvation of the homeland — and “punishment” — for traitors — above divine law. There is, in Creon, no conflict between the interest of the ruler and that of the community (or the governed), with which many types of tyranny are connoted: but between divine law and political institution. Polynices’ “condemnation” and departure from traditional law is necessary, in Creon’s view, for the good of the polis and political expediency.

From another – and close – aspect, Creon’s problem is the treatment (of the rules) – to be applied to the enemy, different from those to be observed for friends (in the political sense). It is the problem of the friend/enemy, which generates the diversity and distinction between internal and external law, still persisting in public law, and a prerequisite of the norm of the laws of the XII tables adversus hostem aeterna auctoritas. Thus, it is the membership (and boundary) of the political community that determines the applicable law. If Polynices, despite being a friend (as a member of the polis), acted as an enemy, the conflict between the two systems is particularly acute, because it also becomes a possible cause of dissolution of the political unity. Thus, Creon motivates his edict, granting that Eteocles: “who died fighting in defense of this city, making a great display of valor with the spear, should receive burial and have all the lustral offerings which go underground to the deceased heroes. But his brother, Polynices I mean, returned from exile wanting to completely destroy with fire his homeland and the gods of his race, wanting to be satisfied with the blood of his own and to bring others into slavery: and as far as he is concerned it was ordered to the city that let no one honor him with tomb and mourning, but let his corpse be left unburied, food for birds and dogs, shameful to behold.” On the other hand, in the dialogue of the second episode between Creon and Antigone, while the latter insists on the quality of Polyneices’ brother, he replies that “but the enemy is never dear, not even when he is dead”. Being an enemy prevails over both philia and adelphia. Connected to the problem of the distinction between internal and external law, between law applicable to the enemy or to the friend, is that Creon absolutizes both the enemy and the command and the function of authority. The enemy is entitled not to chivalric treatment, but even to a condemnation “in the afterlife”, therefore, the decree of the polis and of those who represent it prevails over traditional and “divine” law.

At the same time the enemy is, in Creon’s words, only a public and not a private enemy, hostis and not inimicus. While in the Republic the definition of justice that Polemarchus rejects (and Socrates rejects) is that it is “the art of bringing advantage to friends and harm to enemies”, but in the context of the discussion the meaning of this distinction is not political, that is, it refers to the public, but to both public and private relationships,” in Creon’s words the enemy, to whom he reserves the worst treatment, is that of the polis. It can be said that the enmity is so absolute that it continues after the victory and even the death of the enemy.

At the same time, Creon absolutizes command, as is clear from the governing “manifesto” he displays in his own entrance.

And this is not only and not so much because of the “decisionist” trait and all directed to the salvation of the polis as the first duty of the ruler (and citizens), whereby he considers, to that end, even traditional (and divine) law amendable and derogable; but even more so because of how he emphasizes command over consent.

From the first lines it appears that the people (made up of the choir and the corypheus) little or no share the monarch’s decision, without thereby shaking him from his certainties. But it is quite evident in the comparison between Creon and his son Haemon. Haemon maintains that the father, to whom he pays respect and filial devotion from the very beginning, must take into account popular opinion, which criticizes Creon’s actions and “cries this girl saying that she is the most undeserving of all women to die like this unworthily for most glorious deeds”, for which he prays to the father “do not carry within you only this idea, that what you say is right, and nothing else”. When Creon replies that Antigone is rebellious, Haemon insists. In a rapid series of jokes there is the expression of his position: “Not so the people unanimously say, here in Thebes… Can’t you see that you spoke in a childish way? There is no such thing as a city that belongs to just one man…. Of course, you would rule well alone on a desert land.” But Creon is adamant: to Haemon’s arguments, all based on the public, and specifically on the balance between “leader” and “follower”, command and consensus, Creon rejects Haemon in private, reproaching him for recommending pardon for Antigone only because it is his betrothed, and therefore to be a slave to a woman (with this he insists on the “political” relationship between male and female principle (attitude), which is underlined by Hegel). Haemon, according to Creon, speaks and acts for private purposes, by feeling and not by reason.

Even faith in human reason is in fact characteristic of Creon, as it appears from various passages of the tragedy, in particular in the first episode and in the first stasis. Creon rejects Coryphaeus’ idea that there was divine intervention in the burial of Polyneices: “you say something unbearable, stating that the gods worry about this corpse”. And he attributes the act to a conspiracy of opponents, who bribed the guards. An entirely earthly and rational explanation that excludes divine (or “magical”) intervention in human affairs. The dialogue with the guard is followed by the singing of the choir in the first stasis, a splendid praise of human ingenuity, which has subjugated and used land, animals and plants with its own creativity; it has organized community existence with laws and yet, in the face of these marvelous results, the (claimed) human faculty of choosing (and discerning with reason) for good or for evil remains. Which is an equally positive and “rational” observation of Creon’s theses. And which contains the (possible) prevalence of a reason oriented towards evil, disrespectful of laws and divine justice. The contrast, often repeated in the history (and theory) of law and the State, between the ordering capacity of human reason and conscious decision and natural and “divine” order (which is opposed to that judged to be the fruit of hubris) is here formulated, on the one hand in Creon’s statements, on the other in Antigone’s protests. It is a fact, moreover, that the Enlightenment legislateur and the connected trust in human reason was modeled by Rousseau and Mebly on the Greek models of reformers-ordinators, recurring in Greece from the 6th to the 4th century BC, who with their reforms had innovated and reformed the traditional (and “natural”) order of the polis; and Antigone seems to presuppose this historical process. Of which Sophocles glimpses the limits, and the end of Creon, despiser of the gods and divine and traditional laws, (who loses his family) warns not to exceed. A very similar theme would have recurred, after the Enlightenment and the Revolution, in the criticisms of established (and voluntary) law formulated (already in the Napoleonic period) and then during the Restoration and throughout the 19th century, common both to counter-thinkers and revolutionaries, than to the German jurists of the historical school, to the first sociologists and to socialists like Lassalle, despite their different positions and arguments.

In fact, in the reproaches made against Creon there is another one, equally close to the previous one and significant: that he has inverted (and violated) the relationship between law and order. The latter is understood as a natural rather than human order. In this sense, the choir’s song in the second stasimus of Oedipus Rex is particularly significant: “May I have the destiny of maintaining holy purity of words and actions, over which sublime laws are entrusted, procreated in the celestial ether, and Olympus only he is their father; no mortal nature of men generated them, nor will oblivion ever quell them: a powerful god is in them, and does not age. Excessiveness breeds tyrants. But if someone proceeds superbly in actions or speeches, without fearing Dike and without respecting the seats of the gods, bad luck befall him for his unfortunate pride”; but even more so is Tiresias’ prophecy to Creon, which can be interpreted as the “indictment” for the monarch’s sins: “And you know well that you will not yet make many quick turns of the sun without repaying yourself , in exchange for the dead, a dead man from your own bowels: in exchange for those up here whom you threw underground, placing a living person unworthily in the tomb; while you keep here a corpse devoid of the infernal gods, without funeral honors, nefarious. This is not in your power, nor in the hands of the supreme gods, rather they suffer this violence from you.”

Creon puts the living underground, and the dead outside, denying their natural destination, violating divine law. Such an act is contrary to order and law, not being in the power of Creon (nor man), nor of the gods. One glimpses in this the telluric foundation and conception of human existence; it is the earth that has the function of sustaining (and sustaining) the living, as well as laying to rest the dead: Virgil’s justissima tellus. Law—the human decree—cannot violate this order; in modern terms, one might say, with Schmitt, that human law presupposes order and not the other way around; and its function is thus only limitedly ordering.

And the pride that makes tyrants and hubris consists in disregarding human limitations in changing the natural order. In this, too, Creon is archetypal of what would be practiced and theorized, still, particularly, in the last centuries of the modern age.

Compared to Creon, Antigone represents the other “horn” of these oppositions. Antigone shows a conception of law, of the relationship between divine law and human decrees, which is summarized in the dialogue with Creon, in the second episode “It was not Zeus who proclaimed that prohibition, nor Dike, who dwells with the underworld gods, established such laws for the men. And I did not think that your edicts had such force, that a mortal could transgress the unwritten and unshakable laws of the gods. In fact these are not of today or yesterday, but always live, and no one knows when they appeared;” in these verses the peculiar characteristics of divine law are indicated: divine authority, “hierarchical” superiority over human norms, non-voluntariness, the mystery of its “genesis”. Over twenty centuries later many of these characteristics were underlined by De Maistre as typical of “traditional” norms, in particular of constitutions. In the last century it was Max Weber, with the—adaptable—definition of the type of legitimate traditional power, who summarized them best “when it rests on the daily belief in the sacred character of traditions that have always been valid, and in the legitimacy of those who are called to hold a authority”. Antigone thereby affirms as the foundation of obedience to the law essentially the subjective judgment of the recipient who conforms to rules imposed by divine authority: a relationship between man and divinity, without the interference (or mediation) of human authority (and politics), to the statutes of which, if in conflict with divine law, obedience is not due. Which is the archetype of (most of) the political theses of revolutionary thought, in modernity mostly united under the right of resistance. But which already appeared to be in contrast with the ethos of the polis. Suffice it to remember that about fifty years after the performance of Antigone (the date of writing of the Crito is doubtful) Socrates voluntarily chose not to escape and die, out of respect for the citizen owed to the organization of its own polis. In the (imagined) dialogue with the Laws it is clear that the laws are one with the polis. From the beginning they present themselves as the laws and the whole of the city (oi nomoi kai tò koinòn tes poleos, repeated definition) and urge him not to subvert it, escaping the death sentence, even if unjust. In fact, “do you think that that City can still exist and not be completely subverted, in which the sentences issued have no force, but, by the action of private citizens, are stripped of their authority and destroyed?” Socrates’ “rebellion” therefore affects the very capacity for existence of the polis; the relationship between it and its laws and the citizen is asymmetrical and not equal: “And if this is the case, do you perhaps believe that there is equal right between you and us, and, if we intend to do something against you, do you believe that you also have the right to do the same things against us?” because more than all it is: “the homeland is worthy of honor, and which is more venerable and more holy, and which is held in the highest degree of esteem both by the gods and by sensible men; that one must venerate it,” “and also suffer if it commands us to suffer, remaining silent, whether we are beaten, whether we are chained, or whether it sends us into war to be wounded and killed, this must be done, therefore this consists in justice: that one must not desert, nor retreat, nor abandon one’s post, but, in war and in court and in every other place, one must do what the Homeland and the City command.”

In the discourse of laws, Antigone’s relationship between man and divinity is replaced by that between man and polis; and one clearly glimpses not only the individual/personal character of the former and the suprapersonal/collective character of the latter, but also in germ the main connotations of the concept of institution: those of power (aimed) at order, according to a directive idea. Connotations formulated as a Greek of the classical age of the polis might have done, but which can be likened, even with differences, to as expressed by Hauriou. The superiority in connecting and consolidating the social group of the latter over the former is given by the resolution of the problem of quis judicabit, by confirming or reserving to the institution the powers to decide what is law, what is to be applied as such and executed as such, and by whom, what, if left to the conscience of the individual, becomes, in politics, insoluble (in theory, no: it is enough to imagine a society of wiser men endowed with the congruous intellectual capacities and the necessary moral uprightness).

In Antigone’s discourse, the relationship between politics and law is, consequently, reversed: whereby the one does not dominate this, but rather is subservient to it; whereby the remembered saying salus rei publicae suprema lex does not apply, but rather fiat justitia, pereat mundus in which justitia is what appears so to the citizen. In this, too, Creon’s “modernity” compared to Antigone is evident: while his choice is public in character, because, as Freund argues, the public is first and foremost, an affirmation of unity, the latter leads to a dissolutory choice and outcome, essentially traceable to the private.

And indeed, Hegel’s insight that sees in Creon and Antigone the opposition between male and female element, which then becomes between family and polis can be interpreted as a moment of an evolution-transformation, in which the political and thus decisive character has shifted from the family (understood as a human institution based on relations of consanguinity) to a larger social group: with relative “expropriation,” of the powers of command, of distinction between public and private, friend and foe, in favor of the higher institution.

In every such process (so in the transition from feudal to absolute monarchies) a common and recurring connotation is the deprivation of political and largely, and more generally, public powers to those under-ordained; as well as opposition to any encroachment of the “dispossessed” into the functions reserved for political power; which without those could not guarantee unity.

Depoliticization, is also, and primarily, a privatization: while the “dispossessed” only represent themselves by being (reduced to) private, public power represents (and guarantees) political unity.

The modernity of Creon’s position therefore follows from his ability to ensure political-social unity and order. To which the exercise of command is essential: the human relationship between man and man, the one commanding, the other obeying. All considerations that would emerge and formulated, clearly and distinctly, by Thomas Hobbes. For the Mulmesbary philosopher, the established social relationship requires (a covenant between men legitimizing) the power (of command) vested in only one or a few; the latter have the power to order and enforce their commands. To whom obedience is due, as long as protection is assured; it is the relationship between protection and obedience that legitimizes political power and thus makes and keeps society orderly.

At the same time, power, command, obedience, (compulsion) are relations between man and man, not between man and norm, nor between man and deity.

In order to have Creon punished, in fact, Sophocles brings in (though not in the form of a theatrical character) supernatural power: absolute human power can only be opposed by an even stronger power, which, however, cannot be human. Obviously since supernatural intervention is excluded in a modern and thus secularized view of politics and the state, the only “vision” that can be proposed is that of Creon.

In this regard, what confines Antigone’s position in the non-juridical (in Creon’s sense) are two things above all: the first is the individualistic character: the decision as to what should apply as a rule applicable to the case is left to the judgment of the individual: with this comes the loss of both the necessary heteronomy of the juridical, articulating itself both in the moment of the position of the command and in that of its application/execution.

If, in the species, divine law can be conceived as heteronomous, surely what matters most, namely its application/enforcement, is not. Antigone’s position is relatable to a moral, rather than a legal, reality (or norm). That it is confirmed by the fact that Antigone’s divine law can be applied and executed apart (both in theory and in practice) from any relation to men and the human community: which in the present case appears only in the guise of a prohibition to what Antigone realizes (and carries out). Only that law (and state) presuppose order, command, power, all relations between men and with men, as mentioned above. Which excludes that, in the case, there can be an intervention of application/enforcement of divine law, with sanctions to the transgressor; since this, like the rest presupposes human power (precisely what Antigone disputes or considers irrelevant).

In a sense, it is not even assimilable to a Christian view. While Christianity recognizes a divine law, it has nevertheless conferred the character of a divine institution on human authority as well, while connoting Antigone’s position are the divine institution of the law, but the wholly human character of authority and, alongside, the reservation of the decision to the person. In Christian theology, conversely, human authority is also regarded as a divine institution, as follows both from the well-known passage in St. Paul’s “Epistle to the Romans” (13:1) and from the well-known Gospel phrases whereby jurists such as Hauriou and Carré de Malberg have distinguished between the doctrine of divine supernatural law and divine providential law essentially taking up the main theses on the point of modern Christian political theology.

This made the appeal to divine law, in a Christian society, not a matter of personal judgment, but surrounded by conditions and requirements. The treatment of tyrannicide and sedition is an example of this: almost all theologians, both Catholic and Protestant, legitimize one and/or the other if there is a prevailing public will oriented toward dethroning the tyrant, because tota respublica superior est rege, and all, moreover, under certain conditions, different if the tyrant is such absque titulo or quoad regimen ; and, what constitutes the essential difference, the “contestation” of authority is always made in function of and in view of a different authority, that is, in an institutional context; and having a public character rather than private claims/ demands, as, to a large extent, those of Antigone appear.

While Creon’s position is within (and in function of) a human social group, with its patterns of order, assumptions and relationships and related concreteness, Antigone’s, as mentioned, is a relationship of consciousness to divinity (law, norm), that is, to an ideal and (if not) abstract dimension and entity.

Creon’s theses are rational because they explain the reality-and the possibility of existence-of a human community; Antigone’s cannot constitute anything politically concrete and structured.

Returning to the relationship between politics and law (in the sense in which the latter is seen by Antigone), the opposition between the one and the other is particularly evident in the affair of Polynices, which resembles, in some respects, Antigone’s choice: for Polynices claims to himself vis-à-vis Eteocles the sovereignty of Thebes, because so agreed with his brother. It is thus the claim of a subjective right (jurists would say) for the realization of which Polynices promotes a coalition of Argivian kings in order to conquer Thebes, drive out Eteocles and rule the city. Since, however, the Argives, like all conquerors, do not resemble Farinata degli Uberti, this choice means working for the defeat of the homeland and the ruin of their fellow citizens, so accurately described by the chorus of the Seven at Thebes. Polynices too – indeed far more than Antigone – puts his own right before the salvation and preservation of his homeland. Justice guides him: he has had a woman chiseled into his shield, leading a warrior; this woman “Declares herself Justice, in the writing, and proclaims, ‘I will lead this man lord back to Thebes and to the homelands.’” Faced with this, with the news brought to him by the messenger in The Seven against Thebes, Eteocles’ indignation is great, such that he is compelled to fight Polynices in person, even though he is aware that he is facing death.

It was Eteocles himself who, in so many verses of Aeschylus’ tragedy had called the citizens of Thebes to the defense of the homeland “Now to those of you not yet laughing at the flower of youth, to those who withered in time, to your task each, succor this city, the altars of the patriarchal gods, to whom no honor is extinguished, and the children and the sweetest nurse, Mother Earth, who to you tender ones unsteady on the benign soil, accepted all the burden of raising you, nurtured faithful citizens at the juncture to bear the shield in her defense” and also, designating Melanippus to defend the first gate of Thebes he says, ‘Will resolve the event Ares with dice, but justice of blood he thrusts shield to his mother against hostile spears,’ as Megareus to defend the Neitae gate, “but he will pay by dying his tribute to the land nurturer, or, having captured those two and the city feigned on the shield, adorn his father’s atrium with spoils;” and denying that justice is guide to Polynices “And if Jupiter’s virgin daughter Justice were in deeds and thoughts with him, the wish perhaps was fulfilled. But neither when he fled from his mother’s dark womb, or the nurse raised him, nor boy, nor then that thickened in locks the lint on his chin, did Justice ever deign him a greeting. Nor do I think now assists him in the breakneck of his country, Justice, to deny his own name, friend to an evildoer.”

In the Eteocles-Polynices pair we find the opposition between right founded on a claim of the individual and—conversely—on belonging to a community, as in a more nuanced way between right and politics. Even if founded, Polynices’ right cannot be asserted against the (own) polis; it is the polis that constitutes and guarantees order and thus prevails over individual rights: nor are claims valid against it unless recognized within (and by) the system.

Eteocles’ position at a more dramatic and political juncture corresponds to that of Socrates, who sacrifices to the order of the polis his own chance to have his life saved. And the order of the polis is a concrete order: paralleled in the speeches of Eteocles and Socrates is the call of the homeland as mother, which nurtures and nurtures and thus enables the ordered existence of citizens.

The events of Polynices closely recall those of another hero, Roman and not Greek: Coriolanus. He, too, was exiled for a decision he felt was unjust, and for this, returned at the head of an enemy army to lay siege to Rome. Dissuading Coriolanus here too is a woman, his mother Volumnia. Who by speech—of high dramatic power in Plutarch’s account—more endowed with masculine than feminine spirituality (to follow Hegel), actually accomplishes the synthesis of the (spirituality) of the family and the polis. Volumnia speaks as the (physical) mother, but her words are also those of the political mother: she is aware that if Coriolanus follows her exhortation, he will be killed. But in the decision between the homeland and her son’s life (i.e., between public and private) she has no hesitations or doubts: she sacrifices private feelings to the salvation of Rome: and she exhorts her son to do the same: “Why are you silent, O son? Is it perhaps that it is noble to abandon yourself completely to wrath and rancor while it is dishonorable to yield to the mother who addresses such a grave prayer to you?… And to no one like you would it be fitting to observe the duties of gratitude, to you who so harshly avenge ingratitude. And yet, though you have amply avenged yourself for the fatherland, to your mother you have shown no sign of gratitude.”

Coriolanus makes the choice advocated by his mother: save Rome and be killed by the Volscians. The Roman’s behavior is the opposite of Polynices’: the existence and salvation of the homeland are worth more than individual rights, however well-founded, and the spirit of revenge. More generally: the events of Polynices and Coriolanus prove how often, it is the (subjective) right that is the occasion (justification and pretext) for war; it is, contrary to what happens in Antigone, the family and political relationship are not in conflict, but synergistic in Volumnia’s discourse the mother is at once she and the polis, but the opposition family and polis (and evident in episodes of the earliest Rome, such as the purification of the third Horace for the killing of his sister, betrothed to one of the Curiatians he killed) has been resolved in a synthesis that sees the polis “encompassing” and “overcoming” the family; and the right of the polis prevails over the family.

Given that Creon does not fit into the “classical” type of tyrant, that is, the ruler with little or no solicitude for the bonum commune (which is the first criterion for identifying tyranny, as mentioned above), what does his hubris consist of, which made him one of the figure-symbols of the tyrannical abuse of power in the eyes of a Greek (and others).

Explaining this is Sophocles himself in the second stasimus of Oedipus Rex, when the Chorus states, “disproportion (hubris) begets tyrants,” ubris psyténei tyrannon (see above).

Perhaps the translation of hubris into “immoderation” instead of the more literal “pride” or “arrogance” is the key to understanding Creon’s error. One could for the purpose turn to that typically Greek conception of kosmos as the order of creation, as opposed to khaos, and more specifically, to the Apollonian spirit, which, as specified by Spengler organizes the world into precisely delimited, harmonious and therefore ordered forms.

In such an organized space, limit and measure are, particularly the former, essential concepts; so that the disproportion (i.e., the erroneous—or intentional—failure to observe calculation/evaluation) of the limit constitutes a vulnus to (political and metaphysical) order. Therefore, Creon errs: because he has not taken into account that order (of which divine law is an expression) has been violated by the decree on Polynices; and even more so that it is not in man’s power to violate that order. The disproportion consists in having violated the limit to human power: a limit that is first metaphysical than political.

Next to that what remains of Antigone’s position after millennia of “statute” law and “rational” politics (though, I hope, interspersed-even for centuries-with returns of “traditional” law and politics influenced by “values” that are anything but rationally justifiable).

It is precisely the limit: if Antigone’s position appears “old,” in the end it is not irrational. It is not if one thinks carefully, to rationally evaluate (with respect to purpose) Creon’s decree; what is the point, having won the war (different if the war were to be won) of “condemning” the defeated and dead enemy? Is it rational with respect to the need to protect the safety of the polis? After all, Creon’s decree appears to be the forerunner of the practice, widespread in the last century, whereby war ends on the battlefields, only to continue immediately afterwards in a trial, in which the vanquished are publicly judged – with the forms, sometimes, but always without the spirit and minimum prerequisites of justice—by the victors. A practice contrary to Christian political theology, and to the “classical” international law that owes so much to that.

Teodoro Katte Klitsche de la Grange is an attorney in Rome and is the editor of the well-regarded and influential law journal Behemoth.

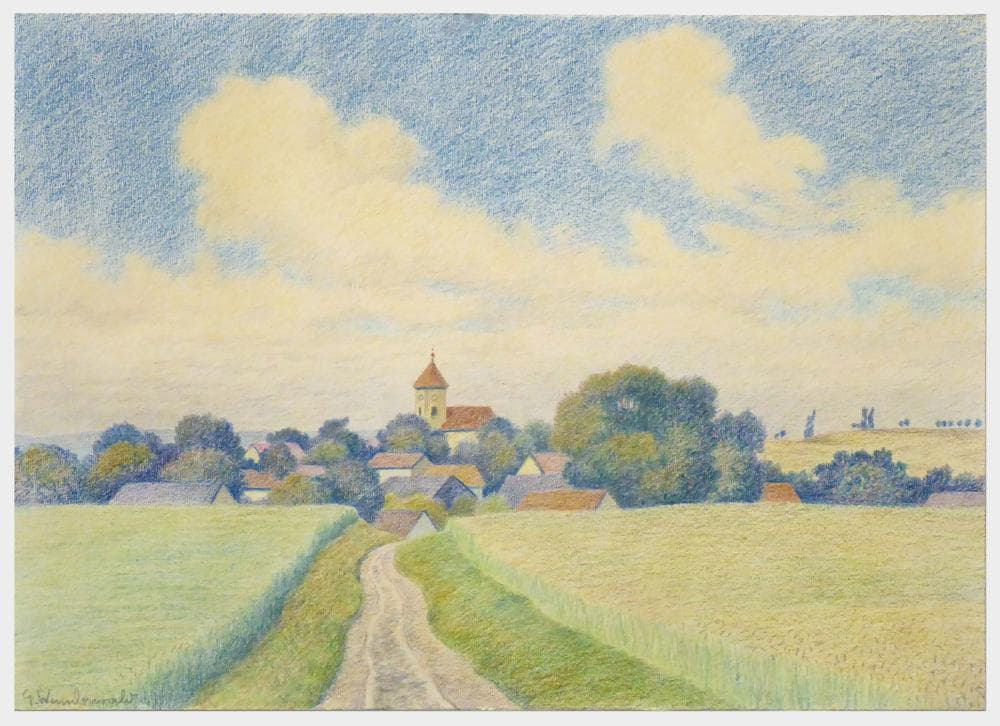

Featured: Antigone Condemned to Death by Creon, by Giuseppe Diotti; painted in 1845.