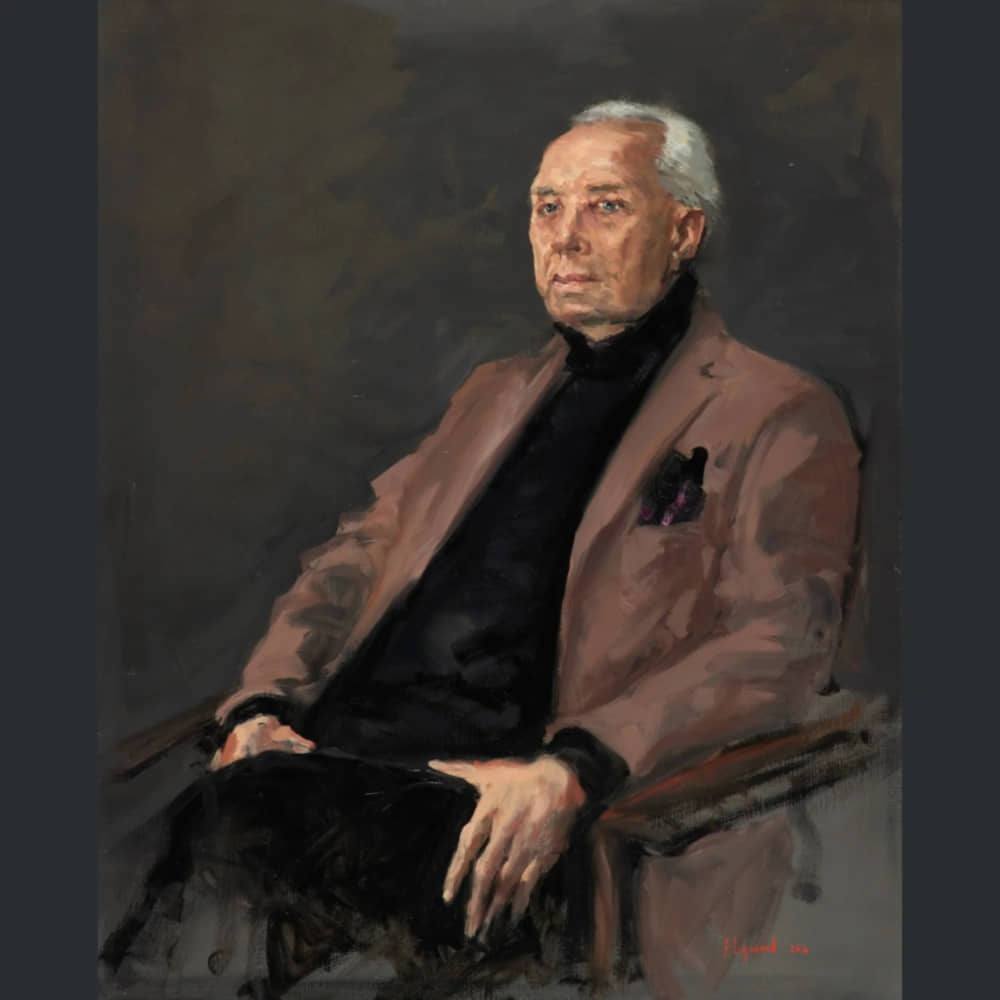

There are men whose very appearance makes them sturdy and dazzling; at times sober, at times flambotant; who say everything and justify everything, like a crusader’s armor or a bishop’s paramour. Marc Fumaroli (1932-2020) was one such man. His attire was always impeccable: three-piece suit from Arnys, club tie, velour jacket. He went with the old buildings, the silks and the tapestries, belonging to the altar as well as the throne. If elegance, the last marker of civilization, was to put forward its man, both a great academic and an eminent man of letters, then it could be none other than he, among the great Frenchmen of our time.

One does not need to be a great soul to see that the world of the university is a cesspool, made up of people who have sacrificed everything to it. If they succeed, it’s because they had an idea once long ago, which they keep recycling for years on end, and rest on comfortable academic laurels. Their bourgeois conformity outweighs their worldliness, and if they dare to think, it is often sideways.

There are however some great names, some beautiful figures, who have understood everything, acquired everything, conquered everything. “Fuma” had the insolent lightness to float in the honors, to hold a bibliography as a work; and this way to be a library addict and to give thanks and account with measure; to arrive at fascinating ideas, the whole formulated by admirable syntheses, handled with panache. His Excellency Fumaroli was of those breed of lords, if I may say so, to which Albert Thibaudet, Julien Benda, Claude-Levi Strauss, Roger Caillois or Paul Valéry belonged; these people of letters with superior intelligence, extensive science, profound erudition, and substantial traits that we lack.

The work of Marc Fumaroli is abundant but concentrated around a beautiful unity: the Europe of letters, ideas and spirit. It would be too long to elaborate it in detail, but let us note the importance that his Eminence gave to the Republic of Letters and the circulation of ideas, from the humanists to the 18th century salon; to this Europe that spoke and wrote in French. In the field of rhetoric, of which he held the chair at the Collège de France, the master was interested in its modern leanings and in the reception of Greek and Roman rhetoric in the Grand Siècle, mastered and studied earlier by Professor Laurent Pernot; hence the remarkable pages devoted to the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns.

Above all, Fumaroli was a literary historian who devoted part of his research to the history of the French language, to the institution of the language and to the way in which France became aware of the greatness and the supreme and precious good of its language. Hence the genius of the French language, the lavish allegory, and the Académie française. The notion of taste animated in a particular way the work of this prince of letters, with all its variations, the nuances between the style and the sensitivity. One might see finally, in the twilight, an old man rehearsing the correspondence between the arts, passing from literature to painting, from poetry to sculpture, declaiming his love for Watteau and Fragonard; the last refuge, if it is such, of beauty and elegance.

Fumaroli was of the Right. That is understood. Liberal, he was close to Raymond Aron; conscious of the inequality among men; vindictive towards egalitarianism. The cultural state he never forgave, and yet incisive as a cut of knife on steak he hinted at a theory of the free arts and the freedoms in the most priceless of art, right in front of the sad passions of the sinister Jack Lang, from the cultural to the sewer.

Nationalist and sovereigntist, Fumaroli was hardly any of that. Deducing that custom is better than reform, he was conservative. Reactionary, he conceived the love of the glorious past and of the monarchies of the Ancien Régime, nostalgic of the big and beautiful Europe, of the books, of the thought, of the great names.

His sharp pen, shielded under some corduroy and tweed canvases, could be acidic, even malicious. When a socialist circular sought to impose the feminization of the names of professions in French, he could refrain from irony and brilliant wit: “notairesse (“notaryess”), mairesse (“mayoress”), doctoresse (“doctoress”), chefesse (“chefess”)… rhyme importunately with fesse (butt), borgnesse (“one-eyed woman”) and drôlesse (“hussy”), only very distantly evoking a duchess. Let’s choose between recteuse (“rectoress”), rectrices “rectrix”) and rectale (“rectal”)…”

In the posthumous book just published, Dans ma bibliothèque, la guerre et la paix (In my library, war and peace), Marc Fumaroli expresses once and for all his views and observations about Europe. Like ideas nurtured for decades, this old man in his green suit delivers a fascinating cornucopia, made incredible by the truths that it delivers, all the ideas that are linked. As the author indicates, this book does not follow any method. Rather, it is a ramble, which follows winding paths, forks in the road, deviations.

The book sometimes gives the impression of a messy work, where the author puts down everything he knows, adding reference after reference, one idea after another, giving the feeling sometimes of losing his purpose – war and peace. It must be said that we are far inferior to the master in following him. It is Europe that we hold in our hands; just like that feeling with la Litterature europeenne et le moyen age latin (European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages) of Curtius.

It is not possible to repeat all the ideas put forward in this book by Marc Fumaroli, so numerous are they. But here is its essence – war and peace have been two opposite poles that have built European civilization, a creative and destructive principle, a kind of duet in which one part does not go without the other; but also a duel that feeds, according to the reigns, wars and peace treaties, artistic creation, taste and consciences.

Thus, Fumaroli developed and detailed an entire triptych. The Iliad and the Aeneid are, first of all, founding texts of war and peace. The Greek work resembles a perpetuum mobile of conflicts between lordships, as one finds them in the Italy of the Renaissance, which fed the history of men like a kind of dynamic.

The Trojan war had a moral reason – the unfaithful wife and the deceived husband; but it does not have a political or economic purpose. Menelaus returns with his lady; Agamemnon is murdered; Achilles as well as Ajax are killed; Ulysses struggles to return; and Aeneas has an appointment with his destiny. War does not create vast ensembles; it sanctifies lives and destinies.

As for the Aeneid, it prepares Rome. Aeneas is, before being a pious civilized warrior, a diplomat who prepares the reign to come of Augustus. The Latin work announces the pax romana, based on the need to make war to impose peace, the perpetual peace, that we will find in two times – at the time of the respublica christiana, developed by Augustine in the City of God, and then with the Treaty of Westphalia, following the Thirty Years War.

Fumaroli masterfully devotes a large part of his work to France, mother of ideas, arts and letters, domina of Europe from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century: “Richelieu invented the concept of the European concert. He made the European Republic of Letters admit that the role of conductor was reserved for France.”

Peace and war marked the reign of Louis XIV; and Versailles, as the center of Europe, illustrated, by its opulence and splendor, this opposition. The Hall of Mirrors presented to the world the true power of France – it was France that made war on Spain; and above all it was France that imposed peace on Spain. The disastrous outcome of the War of the Spanish Succession, the libertine regency and the bankruptcy, paved the way for a kingdom less sure of itself, in retreat on the geopolitical level, acquiescing to peace.

War and peace were also embodied in two characters: Bossuet and Fénelon. One was a supporter of a Gallican Church, quick to serve the altar and the throne; the other, a critical observer of power, who made ready, according to the theory of quietism, a desirable pax catholica in Europe at war. This peace was the message delivered by les Aventures de Télémaque (The Adventures of Telemachus), a book of bedside reading and of apprenticeship, for the young dauphin, written by Fénelon.

Only the century of Louis XV was one of weakness – the aristocracy was more and more autistic and did not play its role anymore; the bourgeoisie got ready for the next coup d’état – that of 1789. Finance and technocracy joined forces. War was no longer of any use. It is then that one realizes with Fumaroli, that peace is not a value in itself nor war a moral fault or a misfortune; and that, conversely, a war contributes to glory and peace, and peace leads to weakness and failure.

As well, Fumaroli showed the rise of a royal art. This Louis-Quatorzian art, if not a baroque art, borrowed from papal and Catholic Rome, and is properly Gallican on the one hand, perpetuated by the rocaille, country style of a Watteau until 1740, then formed by Greek and Roman art, marked by the conflict between the Ancients and the Moderns: “[This art] concealed in France the fundamental historical quarrel about the establishment and the legitimacy of the French absolute monarchy, a quarrel whose echoes resounded in the favorable ears of several Jansenist circles of the kingdom. The court of Versailles took sides during the lifetime of Louis XIV for the Ancients, which it endowed in 1701 with an Academy of Inscriptions.”

The Comte de Caylus was a craftsman. This man is both unknown and impressive. An antiquarian, he had, in the sense that the literary gives it, the vibrant passion and the sensitive taste of antiquity; engraver, archaeologist and aesthete, he knew how to give the impulse of antiquity to the taste and the aesthetics of the kingdom.

At first, close to Watteau, whose biography he wrote, he spoke of the complicity of a generation which had altogether been distanced from war and brought closer to the arts of peace: “The tender memory that I keep of Watteau, of the friendship that I had for him, and of the gratitude that I had for him all my life, led me discover, as much as it was possible in him, the subtleties of his art.” Caylus broke with Ovid and was renewed by Homer and Virgil, just as he broke with Watteau, and the shepherds, and the gioia di vivere. With Wickelmann, he shared the feeling of having come too late; therefore, he mourned, nostalgically, for the ancient world. The return to Greek aesthetics implied, if not a rebirth, at least a return to war, to the martial tone and to heroic assurance in the arts.

The last part of this triptych covers the twentieth century and the emergence of nationalism with Tolstoy’s War and Peace and Grossman’s Life and Fate. The liberal and romantic inspiration contrasts with absolutism and royal dynasty. Something deep and visceral accompanies the formation of nation states. Napoleon waged wars of conquest, a “crusade for nothing,” as Léon Daudet would say, in the name of an expansion of an idea, that of French universalism, born of the liberalism of the French Revolution. The nation as an everyday plebiscite, according to Renan, is formed by the adhesion of a people.

All this is summarized by Fumaroli, in these words: “It is not a king who makes war on another king nor an army on another army, but a people against another people.” Here is Europe, determined amidst the emergence of nations and the fall of empires. Modern war compared to the classical, ancient war, shows a qualitative leap.

Fumaroli reminds us that modern war reaches the degree of destruction that is attributed to it by the number of soldiers that it digests and carries, the mass levies that the nations have, the patriotism injected into the consciousness of war that formalizes and freezes the belligerents, the use of materials such as coal and the use of technology. War and Peace is the modern version of an Iliad, where the death of Prince Andre, mowed down by a French bomb shrapnel on the battlefield of Borodino, is the equivalent of the death of Hector under the blows of Achilles in Book XXII. The implacable Fate of Homer is transported into the mystery of the God of Christian love. And Fumaroli takes up the association of peace-corruption and war-salvation for the 19th and 20th centuries.

Life and Fate, as Fumaroli points out, recapitulates the poetry of the two great ancient epics, the Iliad and the Aeneid, divided between the celebration of noble warrior heroes and the curse of battle and its ignoble massacres. Grossman’s novel is torn between goodness, hidden in the description of the mutual relentlessness of the fascist and Soviet evil against the impervious goodness that perseveres beneath the apocalyptic surface of the Final Solution and the Battle of Stalingrad. The madness and mystery of war. Tolstoy’s Homeric heroes are succeeded by two totalitarian democracies. inspired, says Fumaroli, by France of Robespierre’s Terror and by Bonapartist absolutism, “engaging more decisively in mass extermination at home and mass warfare abroad.”

With regard to the last part of the triptych, we can make three observations. First, this Mitterrandian vision of a nationalism that leads to war seems rather stale. The idea that Napoleon is the origin of a degeneration of European consciousness and the father of conflicts between nations, which was good enough to explain the Second World War and totalitarianism, is now somewhat outdated.

Nazism is not, then, the consequence of a nationalist sentiment, of a love of one’s country, of a desire to be at home. It is a German problem in Germany. Nazism, even if it is extreme right-wing, is an idealistic and biological productivism that is strictly German; and it is a mistake to believe that all nationalistic paths lead to it. It is not a nationalism that metastasized but, on the contrary, in the wake of the concert of nations, the expansion of a great European project, of which the Reich would be at the head; a project that rebuffed the old generation of Action Française. such as, Maurras or Bainville, nationalists, and which delighted the Lucien Rebatet, Brasillach or Leon Degrelle, fascists. This literary and intellectual point and this quarrel of generations are both missing

If Europe, finally, is better than nationalisms, and if greater Europe interests us, what is the political purpose of this one? Who leads Europe? Which institutions? Which country? Who has the power? The European Union? This vast joke cannot satisfy us. How can we believe that European technocracy, co-opted, would find the necessary resources to substitute itself for elected monarchs, presidents and ministers, subject to a vote?

Now, there will be no more Fumaroli. Our Cheetah has made his last turn. Going through the whole of his work on war and peace, one can resolutely take up the phrase of Marshal Lyautey, “But they are crazy! A war between Europeans is a civil war.”

Nicolas Kinosky is at the Centres des Analyses des Rhétoriques Religieuses de l’Antiquité. This articles appears through the very kind courtesy La Nef.

The featured image shows, “Portrait of Marc Fumaroli, seated,” by François Legrand; painted in 2014.