There is currently a debate about the usefulness or uselessness of history for postindustrial or postmodern societies. While some authors argue that history has entered into crisis, others continue to proclaim its vigor and believe in its validity, whether in its more traditional forms, as evidenced by the return of politico-military oriented historiography; or in other forms, more adapted to the world of the image and mass media. In the latter case, highlighting the link between historical knowledge and the notion of heritage, which can bring with it the danger of trivialization and commodification of this old knowledge.

Now, if all this is true in the field of history in general, in the field of ancient Classical history the question arises with an even sharper focus. And this is so, on the one hand, because of the very crisis of the Classical paradigm in the Western world, and on the other hand because the artistic and archaeological wealth of the Greco-Roman civilizations makes them easy prey for the cultural exhibition industry, which still knows how to exploit the component of exoticism that for a long time was associated with the world of Greece and Rome.

It is curious to note that, even among the defenders of historical science (for those who no longer believe in it, the study of the most remote times is evidently no longer of interest), the value of the study of ancient history is increasingly questioned for several reasons. In the first place, because it is a history based fundamentally on the study of literary sources and because of the scarcity of primary sources (inscriptions and papyri cannot be compared in their richness to the documentary sources of the other types of history). It should be noted that, in the opinion of these authors, the abandonment of literary sources is, as Leopold von Ranke wanted it, almost a sine qua non condition for the emergence of history-science. Secondly, those historians who cultivate quantitative methodologies tend to look with benevolence, if not contempt, at historians of the Classical world, because of their evident impossibility of handling this type of sources, almost non-existent in the field of their studies.

And to this we may add the fact that Classical historians have been showing an almost absolute disregard for theoretical and methodological reflection, remaining faithful (especially in England and Germany) to the most traditional ways of doing history, and therefore seem to give an image of outdated professionals.

As if these were not enough, historiographical and ideological debates, such as the one provoked by the publication of Martfn Bernal’s work (1991), with all its replicas, and counter-replicas, in which the clear ethnocentric component, and even the colonial ideology of Classical historians, as analyzed by J.M. Blaut, have come to light, and have put the finger even more on the question of the current validity of this type of historiography

Leaving aside the misunderstanding of different groups of historians towards ancient history, derived from their poor knowledge of it, from their belief in the omnipotence of its supposedly scientific methods, or from their incomprehension of the entire past that is not proximate. What is certain is that we can speak of a certain crisis of Greco-Roman historiography, derived fundamentally from the loss of vigor of the Classical paradigm, a paradigm that is forged in antiquity itself and which it is necessary to examine.

I.

It is evident that the process of idealization of the Greek and Roman past had its beginnings in antiquity itself. This process was centered around two axes: a) the creation of a literate culture considered worthy of imitation; and b) the construction of political models endowed with supposedly supratemporal validity.

To understand the first process, we have to analyze how in the Greek world, fundamentally, there was a passage from a basically oral tradition to the creation of a corpus of texts considered traditional and worthy of study.

It is a well-known fact, starting from the studies of Milman Parry, that Homeric poetry is only explicable if we start from an oral matrix. In the world of oral literature (if it can be called as such) we can say that the pragmatic dimension of language is predominant over the syntactic and semantic component. In this world, it is the context that allows us to understand the meaning of the utterances; and therefore in this world literary creation is the product of a spatial and temporal circumstance, of a context in which the poet and the public enter into communication in the ambit of a situation that allows them to share a series of meanings.

But the Homeric poems were put in writing, perhaps by the invention of the alphabet. From the moment in which this process took place, the texts began to lose their pragmatic dimension and to be transmissible in time, thus creating a literary culture, in which the works that were considered worthy of transmission had to be the object of an interpretation, which in the case of the Homeric poems developed from their first being set down in writing in the Athens of Peisistratos until the Byzantine era.

This process, which Florence Dupont has called the “invention of literature,” was at the time inseparable from the creation of libraries in the Greek world. Whatever the first important library in the Greek world was, whether that of Euripides or that of Aristotle (according to tradition), what is clear is that the library that serves as a reference is the library of Alexandria. In it, the compilation of Greek manuscripts was systematized; and in it also, parallel to this work of compilation, the philological technique was developed by Aristarchus of Samothrace and his disciples who established the editions of the Homeric poems that we now possess, in which we try to distinguish the original from the added.

The birth of philology, in trying to find the original versions of texts and trying to eliminate their contamination with the passage of time, implies an effort to tear the text from its contexts, to eliminate its pragmatic dimensions, thus involuntarily laying the foundations for a process of incomprehension of the text. In fact, by distancing ourselves from the texts in time and losing the context in which they were born, we also lose part of their intelligibility, which makes it necessary to make an effort to interpret them. The effort, in the case of the Homeric poems, or in that of the Jewish Bible in Alexandria in the case of Philotheos, led to the birth of allegorical exegesis. In it, the text hides a message behind the appearance of its literalness. To discover it, a key becomes necessary, which can be euhemeristic (reducing the Homeric myth to a historical event; the naturalistic to a physical phenomenon or to moralizing) to a moral lesson.

In any case, what we are interested in emphasizing is the existence of a distance between the text and the reader, a distance that must be bridged with a hermeneutic effort. In this effort, as H. G. Gadamer has pointed out, two notions are fundamental: a) the notion of corpus and b) the notion of the hermeneutic circle. In the Greek or Jewish case, a culture is defined by the possession of a group of texts considered canonical, which serve to establish its identity. One is Greek because one is situated in a certain literary tradition, symbolized by the Homeric poems that hide the truth of our past and ultimately of our being. These texts, as we say, have to be interpreted; and this is made possible by the existence of a positive prejudice, which is born of our identification with them and leads us to enter into a hermeneutic circle. My identity resides in the texts that encode my past. I am therefore part of them. But to really know myself I have to go deeper into them, which are also something different from what I am.

This interpretative work gave rise to the whole of classical philology, from antiquity to the present day; and, consequently, also to the development of ancient history. Ancient history is within the scope of the hermeneutic circle. But this circle has something of magic about it – we place ourselves in it on the basis of a belief in a certain philological faith; and it is precisely on the basis of this credibility that the vigor or decadence of ancient history derives.

But this process of identification was not only merely literary or religious (in the case of Alexandrian Judaism), but was also, and from this derives its strength, a political process. At the same time that the Library of Alexandria was created, the Greeks colonized the entire Near East. And while Aristarchus was establishing his edition of Homer, the Greek clerics were settling in the Egyptian countryside and fighting in the army of the Ptolemies. In the Hellenistic world the Greeks reinforced their identity against the barbarians, as they had been doing since the Median Wars; and that identity was linked to the idea of their superiority over barbarians, which in turn was derived from the very nature of their political models, as Herodotus tells us in a famous dialogue in which he contrasts the Greek who lives under the law, to the barbarian who lives under the despot.

The idealization of the Greek political systems began in the Classical Period, both in the Athenian and Spartan cases. Sparta was the object of idealization by Plato, Socrates or the Cynics, who made of it a model state for its cultivation of the virtues of courage, austerity and continence, initiating a long process which, as we shall see, continued in European thought with authors such as J. J. Rousseau and others. The same is true of Athenian democracy, idealized in the “funeral oration” that Thucydides puts in the mouth of Pericles and a model to be imitated, both in the Classical period itself and throughout European history.

In the world of politics, however, more than the idealization of Spartan militarism or Greek democracy, which was only revitalized in Europe after the French Revolution, what had greater importance was the idealization of the Roman constitution and the idea of Rome. As it is known, it is a Greek, Polybius, who, applying the theory of the mixed constitution of Pythagorean origin, maintained that the Roman constitution is the best of the possible constitutions and is destined to last in time, because it unites the virtues of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy. Such a constitution, not subject to change, and the efficacy and power of the legion as a tactical instrument, ensured Rome’s survival over time, thus laying the foundations of Roma aeterna as a political myth.

The eternity of Rome, achieved thanks to two new ideas – enovation and enovation, which made it possible to move the empire by Constantine and to invigorate it periodically, gave rise to the Germanic Holy Roman Empire, up to the contemporary age, or to the Second and Third Reichs in Germany.

It was the imperial model that shaped all medieval political theology, starting with Eusebius of Caesarea, conditioning all Western political thought up to Machiavelli or Hobbes, two assiduous readers, moreover, of Titus Livy, in the first case, or of Thucydides in the second.

It was this mixture of cultural tradition with political models, together with the assimilation of Classical culture by Christianity, which kept the Classical tradition alive throughout the Middle Ages, and which laid the foundations, so that with the process of secularization that began with the Renaissance, this tradition would continue to live on.

In the medieval world, the classical tradition, domesticated by Christianity and linked to the development of the idea of empire, had a basically conservative character, since it justified the existing order; it was with the Renaissance, and especially with the Enlightenment, that the Classical world changed its meaning in this respect. The Enlightenment, on the one hand, vindicated the republican ideal, breaking with the imperial idea and with the theologically justified power of the king, and on the other hand, in authors such as F. Schiller or F. Hölderlin, Greece became not only the world of political freedom but also of sexual freedom and freedom of thought, together with the liberation from the notions of guilt and sin, which in Germany weighed especially heavily because of the weight of the Lutheran tradition. This nostalgia for lost love, political and spiritual freedom was expressed in great works of German literature such as Hölderlin’s Hyperion.

But this vein of freedom of the Aufklärung that was politically embodied in the French Revolution could not continue after the defeat of the Revolution; and with the Restoration of the monarchical powers, and the beginning of the 19th century, we see a process in which Classical history, while constituting itself as a science, assumed a conservative character.

II.

The development of Classical studies is inseparable from the study of social history and the history of each culture. So, it is necessary for its understanding to take into account the context of each country, be it Germany, England, France or the USA.

It is not the intention here to carry out a synthesis of Classical history, as this would require a great deal of space, and other authors such as Carmine Ampolo, or Karl Christ have already been doing this. Rather, we will outline which are the images, or metanarratives on which Greek and Roman history has been configured. To this end, we will choose a minimum number of authors; those who created the great overviews of the history of antiquity, starting from a contrast of two focal points: Prussia and England, in the first half of the nineteenth century.

We will start with the figure of Karl Otfried Müller, who with his book Die Dorier, the first volume of what would become a history of the different Greek Stämme, marks the beginning of the scientific historiography of ancient Greece.

Müller possessed an exhaustive knowledge of the sources; but these sources were read by him under a certain hermeneutic key, which is the one we are interested in unraveling. Müller chose Sparta as a place of reference, because he carried out an unconscious process of identification between Sparta and Prussia. The destiny of both was to unify their peoples: Greeks and Germans respectively, to which they were called by their superiority, derived from the cultivation of a set of virtues. Spartans and Prussians were two strong agrarian-based peoples, as was Müller’s Prussia, in which the link to the land and the cultivation of virtues, such as, moderation and military courage, allowed the formation of armies that were called to be the backbone of the new states. Both peoples faced a historical destiny that prevented them from fulfilling their national destiny, when confronted with industrial and mercantile powers of a democratic nature, which prevented their military expansion and the establishment of the aristocratic military regimes of government in which Müller believed.

Müller erroneously contrasted the Doric spirit with the Ionian spirit, making it a supposed key to understanding Greek history and thus distancing himself from historical reality, as E. Will pointed out at the time. If he acted in this way, it was motivated by his political passion. In doing so, however, he did not act in vain, since he created a historiographical meta-narrative that strongly conditioned German historiography, which saw in the aristocratic, military and agrarian values something superior to the English democratic and industrial tradition, believing to find in that vision of Greek history a key to what some have defined as the German Sonderweg, or the special destiny of Germany from the Franco-Prussian War to Nazism.

This conservative tradition about the Greek world was embodied by most German historians and philologists and went hand-in-hand with the process of idealization of Greece in the fields of art, philosophy and culture in general. But it faced in the twentieth century a double process that came to question its credibility. On the one hand, the identification of these antidemocratic values with Nazism caused them to enter into crisis after the Second World War, which consecrated the triumph of democratic capitalist or socialist values. And this, together with the decline of the study of Classical languages, the basis of the elitist education of the Gymnasium (to which five percent of young people between 12 and 18 years of age had access in the 19th century), caused Hellenic studies to lose a good part of their social weight.

But this image coexisted with an opposite one; that cultivated in England by George Grote, a liberal politician, a utilitarian philosopher and a banker, author of the voluminous, History of Greece, which in the mid-nineteenth century laid the foundations of knowledge of the Greek world in England. Grote did not idealize Sparta, but Athens, a bourgeois republic of merchants and artisans, which cultivated democracy as a political form and favored the development of art and culture, together with its economic prosperity.

Athens was the kingdom of political freedom and freedom of thought and also of pleasure for the majority, one of the principles of utilitarianism, in which Grote believed (1876) as a philosopher. Greece became a reference for the development of modern democracies, as it had been since the French Revolution and the predecessor of industrial societies, thanks to the development of its science and technology. But that Greece, incarnated in Athens was also, like England, an imperialist power, mistress of a maritime empire, based not on oppression but on the development of trade and the gentle imposition of a cultural superiority, linked to the development of Classical culture.

It was said in Victorian England that Classical culture, offered at Oxford and Cambridge, was something that, once acquired, allowed us to feel superior to others. And this was due to the small number of students of Classical languages and their high social status, which gave them enough leisure not to engage in a practical activity.

The validity of this model also depended not only on the credibility of democratic values and faith in industrial civilization, but also on the belief in the superiority of Europe over the rest of the world, which was called into question after the process of decolonization that took place after World War II.

If we move from the Greek world to the Roman world in Germany itself, we encounter the figure of Theodor Mommsen, author of The History of Rome, which won him the Nobel Prize for literature. Mommsen was not an ultra-conservative politician like Müller, nor a fervent Prussian patriot like Johann Droysen, the creator of the idea of Hellenism, who thought that Alexander’s destiny should have consisted in fusing the East with Greek culture, thus creating a new culture, the basis of Roman culture, and therefore of European culture. Like Droysen, Mommsen was also a liberal.

Mommsen read the history of the Roman Republic from a contemporary point of view. For him, the confrontation between patricians and plebeians was a confrontation between political parties: one conservative and the other pro-Greece, fighting for access to political power, and consequently to the distribution of public goods that the possession of this political power brought with it in republican Rome. These parties had their own organization and ideology, like contemporary political parties; and the development of their struggles ended with the figure of Julius Caesar and the foundation of the Empire. Mommsen abandoned the History of Rome when he reached the Caesars, perhaps because he could not apply that political logic to the development of imperial history, focusing more on other works, such as the systematization of the systematization of Roman public law or criminal law.

Roman history in Mommsen, or in his great predecessor Edward Gibbon, was associated with the ideas of the Enlightenment. But in it, by a curious paradox, the problem of the decadence, or the end of the Roman Empire, which symbolized the end of a culture also worthy of imitation, became a central theme. Gibbon attributed it, as is well known, to the triumph of religion and barbarism, two antitheses of the enlightened ideal, now curiously associated. The Roman Empire, at the time of the Antonines, was associated with the best and happiest period in the history of mankind, and permitted an understanding of the cause of its end and perhaps could allow for the discovery of the key to the history of Europe. Gibbon developed a progressive historiographical vision, since he was an enlightened man; but after Mommsen, at the arrival of the 20th century, other historians changed the sense of the meta-narratives of Roman history, since Rome no longer incarnated the values of the Enlightenment, as in Gibbon, or the triumph of liberalism, as in Mommsen, but the bourgeois or aristocratic values.

The aristocratic and anti-democratic values were brought to light by prosopographers like Munzer or Gelzer, who overthrew Mommsen’s vision of Roman political parties, showing how on both sides, patricians and plebeians, it was the aristocrats who controlled the political game.

This was so, but its discovery was not innocent, since such theories, as Luciano Canfora has pointed, out went hand-in-hand with the critique of democratic systems by Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca, developed at the time of the incubation of fascism. Both emphasized the apparent rather than real character of democratic regimes, since in politics it is always the elites who, whatever the system, control power.

A particularly important case is that of Michael Rostovtzeff. This Russian historian, author of the groundbreaking Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire, a work of the first magnitude for its use of epigraphic, archaeological and literary sources, interpreted the history of the empire as that of the rise and fall of a social class, the bourgeoisie, builder and creator of the city.

Rostovtzeff defined the Empire as a federation of free cities. These cities were based on the development of trade, industry and “scientific” agriculture and were linked to the life and death of the bourgeois social class. This class entered into decline because of fiscal pressure, which stifled its economic activity and favored the development of the army and the state, increasingly controlled by the peasant masses. The decline of the Roman Empire would thus be a revenge of the countryside against the city. With it, and the death of the city, art and Classical culture disappeared in all its aspects, all of which were creations of the bourgeoisie and the urban world.

Marinus Wes has brought out the concordances between Rostovtzeff’s life and his vision of the history of Rome. Our historian, was a Classicist, and therefore a member of a double minority in tsarist Russia – urban and Western and Classical culture – who identified himself with the inhabitants of the cities in a predominantly rural world, as tsarist Russia was at that time, a world in which a revolution of the lower classes collapsed a political system that had allowed the flourishing of cultured minorities. The fall of the Roman Empire was thus a transcript of the Russian Revolution; and those peasants who controlled the army and the state were a transcript of the Revolt of the Masses analyzed at the same historical moment by Ortega y Gasset (1929), or in The Decline of the West, foreshadowed a few years earlier by 0. Spengler (1923), who also felt himself a prophet of a similar decadence to that of the Empire.

The decadence of Rome thus became a goal of the transformations of the contemporary world and the advent of mass society, rejected by Spengler, Ortega and Rostovtzeff. In this way, the history of Rome became one more instrument of conservative thought, in which there continued to be an identification with the Classical world and its culture, understood as the patrimony of the minorities and as a rejection of the more radical forms of democratic government, embodied not only in the amorphous masses, but in political movements such as socialism.

Leaving aside these conservative visions, which compromised the survival of Classical culture by associating it with their political approaches, we must now look at those visions of Classical history that saw in it perhaps the possibility of thinking about some forms of liberation, as had occurred in the Renaissance or the Enlightenment.

III.

Until now, we have been seeing a process in which Classical antiquity functioned as a paradigm, as a model to imitate, whether from a cultural or political point of view. With the last third of the 19th century, we saw the beginning of a process that had precisely the opposite effect. It was an operation of unveiling, as if an attempt were being made to remove the mask of the Greeks and Romans and to discover behind it a hidden truth that no one had wanted to reveal until then.

The discovery of this truth also meant that the ancient world lost its paradigmatic character on the one hand, but on the other hand, precisely by losing this exemplary character, this world became closer to us. By approaching us it also became more intelligible; but not in an immediate way and through a process of assimilation, as had been the case until then, but through a complex operation, by means of which the proximate becomes comprehensible through its encounter with the alien, which, in turn, is revealed to us as something that could also have some affinity with us.

The first author to participate in this unveiling operation was Karl Marx. Marx was neither a philologist nor a historian of Classical antiquity, which does not mean that he was not attracted by it. On the one hand, like all Gymnasium students, he had a good command of Classical languages, and to Greek thought, in particular to the atomists (Leucippus and Democritus) he dedicated his doctoral thesis, perhaps sensing in them the roots of a materialism that was becoming indispensable, in a Germany dominated by Hegelian idealism.

Marx therefore had a double attitude towards Classical culture. On the one hand, like every educated German of the mid-nineteenth century, he was an admirer of it, and continued to consider Greek art as art without compare, or else admired the results of Greek science and philosophy. But, on the other hand, he discovered a hidden truth that was the key to the whole of Greek and Roman history.

It is well known that in the funeral oration that Friedrich Engels gave at Marx’s tomb, he stated that just as Isaac Newton had discovered the fundamental law that governed the functioning of the physical world and Charles Darwin had done the same with the world of life, likewise Marx was the discoverer of the fundamental law that regulated the course of history, and that law was the “law of value.”

According to this law, in all human societies, we must look for how the process of extraction of the surplus value that the working class produces, and from which the ruling class benefits, is articulated. In the ancient world this process took place either under the form of appropriation of surplus value by the state, more or less sacral, in the Asian Mode of Production, corresponding to Egypt and Mesopotamia. Or when we refer to the Greco-Roman world, the key to its history was given to us through the exploitation of servile labor in its different modalities.

Classical civilization was made possible by the labor of slaves and their exclusion, like that of the Metics, from the system of citizenship rights. The political and economic systems of antiquity can in no way, therefore, be worthy of imitation, but must be judged under an eminently negative gaze, since they contradict our ethical and political principles as they have been formulated since the French Revolution, and whose validity, at least at an abstract level, a large part of European society never grew tired of proclaiming.

But the question does not end here since, discovering in parallel the concept of ideology Marx, and some of his followers in the twentieth century, like Benjamin Farrington brought to light how the Greek philosophy, thus far the philosophy without compare, was also a product of class interests, which were not limited to justify only slavery or political domination of the Greeks over the barbarians, but also impeded the very development of Greek science itself, by preventing it, in Farrington’s formulation, from reaching the threshold of the Industrial Revolution.

Farrington’s theory is based on a clear idealization of Greek science, incapable, by its own internal structure, of developing machinism. By overvaluing that science and making it similar to modern physics Farrington continued with a logic that Marx himself had not completely abandoned – the logic of the idealization of the Classical world, although now that logic was limited to the scope of his theoretical constructions in the world of physics and chemistry.

The revelatory potential of Marxism was thus limited by the presence in it of this idealizing component, and by the very idea of history considered as a science. The idea that we are in possession of a method that allows us to understand the key to history can be a dangerous idea. In the first place, because history is not like a riddle whose resolution brings us great relief and puts an end to the problem. And secondly because if we claim to be in possession of the secret that makes us understand the development of history and society, and we try to apply it to the political level, which is typical if, following the Platonic tradition, we think that the one who knows the most should rule, we will then have to develop a totalitarian system, in which those who are in possession of power are also in possession of the truth in general and of the truth about history, with which the liberating potential of Marx’s theory is reduced to nothing.

In any case, Marx’s contribution is there. Thanks to it, when we look at the Classical world, we can no longer have that old sense of complacency which, as we have seen, had been developing since antiquity itself. In the Classical world there was also a hidden truth, a truth whose discovery we find unpleasant and which, through the discovery of power in its pure state and of economic exploitation without further ado, has come to place the Greeks and the Romans on the same level as the prosaic contemporary world in which Marx and we ourselves have had to live.

In a different framing, but sharing the same logic as Marx, we have to place the figure of Friedrich Nietzsche. Contrary to Marx, Nietzsche was a professional in Classical studies. Professor of Greek at the University of Basel, he was a great connoisseur of the Hellenic world, although many later philologists and historians have refused to assume his legacy, precisely because he questioned the value of Classical antiquity elevated to the level of a paradigm worthy of imitation.

References to the Greek world never ceased to be present throughout Nietzsche’s work; but the most systematic ones are found in his writings of the Basel period and in the work that made him known and which served as a stone of scandal and as the milestone that marked his abandonment of Classical philology. We refer, obviously, to Die Geburt der Tragödie (The Birth of Tragedy).

Nietzsche participated in the same operation of unmasking as Karl Marx. But just as Marx found the secret key to the Greek world outside, in society, in the social relations of production. Nietzsche found it inside, in the soul of the Greeks themselves.

Nietzsche made two fundamental discoveries. First, that the so-called Greek spirit, centered on the idea of proportion of measure and rationality, is but one of the two facets of the same spirit. The Hellenic culture cannot be reduced to a single guiding principle; but that within it nestles a profound contradiction between two elements: the Apollonian, which corresponds to the image that Europe wanted to assume of the Greek world, and the Dionysian, which embodies the powers of passion, irrationality, life, and the surpassing of all limits. It was from Socrates onwards, when the Dionysiac was reduced to second place, and the Apollonian spirit came to predominate, a spirit that reached its most perfect formulation in Plato and that, with the assimilation of his philosophy by the Fathers of the Church, was assumed by Christianity, that kind of Platonism for the people, as Nietzsche himself says.

But this irrational component did not remain in Nietzsche in a mere vindication of passion or the nocturnal and dark aspects of life. Rather, the philosopher showed how Greek culture would have been impossible without the work of slaves and how it was the product of a dominant minority, whether we like it or not. And depending on how we interpret this, we will have the key to the conservative or progressive readings of Nietzsche. The Classical ideal is therefore neither democratizable nor extensible outside the Greek world. The values of the Greeks are not the values of liberal democracies nor those of industrial civilization. The Greek world is radically alien and unattainable to us; but it is not unattainable because of its perfection, but because it implies a radically different configuration of life.

This world has also undergone a process of falsification which has tended to make it reasonable and measured, thus allowing it to be assimilated to the Christian ideals of submission and continence. Our approach to it should, if we wish to affirm the values of life, lead us away from the Apollonian, and ultimately Christian, ideal, and lead us to delve into the Dionysian. The Dionysian presupposes the world of life, of becoming, of the liberation of the passions and of the bonds through which social structures are kept in operation. Access to the Dionysian is the key to any process of emancipation, since our chains are not only on the outside, where Marx had placed them, but also inside ourselves, in our ways of feeling and thinking.

However, as in the case of Marx, Nietzsche was not faithful to his message in the end, since, as Martin Heidegger pointed out at the time, in developing the theory of the eternal return, Nietzsche returned to restore metaphysics, from which he had wanted to flee. In effect, the Dionysian supposes that the ground beneath our feet collapses, that we lose the points of reference that until now have made us sure of ourselves, that we become disoriented. If we do not want to follow to the end this path that might lead us to the madness in which Nietzsche himself spent his last ten years, we would have to combine this process with something that would allow us to return to the outside, to the world. Or, what is the same, to raise that process not as a psychological process, but as a social and historical process, channeling individual liberation in the framework of collective liberation processes that the solitary of Sils-Maria, the follower of Zarathustra, that anchorite preacher who lived accompanied by his animals could not or would not conceive.

A third author who also contributed in a decisive way to the process of dissolution of the Classical archetype was Sigmund Freud. Freud himself said that Western man had to suffer three great wounds to his narcissism. The first was inflicted by Copernicus when he discovered that the Earth was not the center of the Universe, but just another planet among thousands or millions that should not have any privileged destiny. The author of the second wound was Charles Darwin, when he taught us that we are nothing more than another link in the chain of life, a product of a process of selection and adaptation, which can also be destined to have an end and which shares with other living beings most of its characteristics, thus losing the privilege that God had given to Adam and Eve in Paradise, when He gave them the earth, the plants and the animals to establish His dominion over them.

The author of the third wound was Freud himself, who came to tell us that our rationality is only the tip of an iceberg in which the unconscious psychic processes occupy those three quarters that are submerged. Human beings are not defined by our reason, but by our passions, by our libido, which is what configures us individually and collectively, and which manifests itself in its raw state through suicide, mental illness or through collective creations such as myths and rites.

Freud, as a good Viennese bourgeois, also possessed a great Classical culture, and it is curious that it was Oedipus, precisely from the Sophoclean Oedipus Rex, the figure that would serve Freud as a metaphor for the key mechanism that allows us to understand our psychic life: the Oedipus Complex.

Obviously, Freud was neither a historian nor a philologist. But psychoanalysis, as he himself pointed out, has multiple purposes. In addition to being a therapeutic technique, whose usefulness can be accepted or not, psychoanalysis is also a theory of culture, and therefore an anthropology. After Freud, we can no longer have the same image of human beings as before; and this will have obvious consequences in the field of historiography and the study of Classical culture.

We can focus the impact of Freud’s work, in addition, for example, in the study of the interpretation of dreams, about which antiquity still offers us Artemidorus’s work, in the areas of the study of myth and rite and in the terrain of a force, whose importance Freud greatly emphasized, as in the case of sexuality.

Freud, in Totem and Taboo, established a classic parallelism between infantile thinking, the signs and symptoms of neurosis and primitive thought. Today he is criticized for his vision of the primitive, the result not of his invention but of the image anthropology of the early twentieth century gave him. But, in spite of this, his interpretations are of great interest because, in the case of rites and myths, Freud discovered that both possess a logic, but a hidden logic that must be unveiled.

As in the cases of Marx and Nietzsche, we find again the contrast between appearance and essence, with the idea that truth always remains hidden and must be unveiled. In Freud’s case, this unveiling allows us to discover the logic of the irrational, the meaning of nonmeaning, thanks to the method of interpretation of signs based on the principles of condensation and displacement that constantly disfigure the message that the unconscious wants to transmit; although, in the end, this message, thanks to interpretative work, can also be deciphered.

The logic of rite and myth reveals that the former is nothing more than a set of meaningless gestures, and that the latter is not an exemplary story worthy of being remodeled artistically or literarily in a process of endless reinterpretation. Ritual and myth are a manifestation of the desire of the psychic energy that Freud metonymically designated with the name of sexuality.

This energy flows through the same channels in every culture, and therefore Classical rite or myth loses its exclusivity. A Greek rite of initiation need not be different from an African rite of initiation. Comparativism, which the nineteenth and twentieth centuries developed in the study of religion, finds in Freud a secure basis, inasmuch as he believes, like Marx, in discovering the fundamental law; the key that regulates the functioning, in this case, of psychic life, and consequently of society.

But there is another field in which Freud’s contribution was particularly important in the process of dethroning the Classical image. It is the field of sexuality. It used to be said in Victorian times that Greece had committed two great sins – that of slavery and homosexuality. The secret of slavery had been uncovered by Marx. The study of homosexuality would still have to wait a long time.

The problem of Hellenistic homosexuality was perhaps even more serious because it was in fact an institutionalization of pederasty, which was very difficult to make sense of. Some authors, such as, Eric Bethe, had tried to do so by framing it in the world of warrior initiations and trying to erase the images of effeminacy and sexual inversion that the nineteenth century associated with the image of the homosexual.

The path initiated by Bethe was continued in the 20th century by another series of authors, such as Dover, who emphasized its educational and initiatory character, in order to continue to find meaning for it. More recently, however, there has been a change in the approach to this problem, when authors, such as, Eva Cantarella, go on to introduce new concepts such as bisexuality, which breaks the framework of warrior initiations and brings to light the fact that sexual relations with persons of the same sex need not necessarily be a problem to be explained, but may be more or less consubstantial to human nature.

In this sense, the history of sexuality could bring with it a danger: the idealization for the umpteenth time of the Classical world, now considered as a place where sexuality could have developed freely, as it did in authors such as Schiller or Hölderlin. Michel Foucault has warned us against this temptation and has shown how sexuality is not a natural substratum that is always the victim of social repression, and whose liberation, until it reaches its pure state, should be our objective. On the contrary, sexuality is a social construction based on an unquestionable biological basis. A construction that is one of the keys to our identity. The history of sexuality is inseparable from the history of the ego, which is why Foucault used authors such as Plato or Seneca as a fundamental source.

The sexuality-identity correlation is of great importance, since it is evident, from Hegel onwards, that there cannot be an “I” without a “You” and a “We.” Or, in other words, that the individual and society are not two antithetical terms, but complementary. Thus, the aspiration to unite the interior (subjectivity) with the exterior (objectivity), which Nietzsche and Marx had not even achieved, each in his own way, can be possible from now on with authors like Foucault and with the development of the historiography of the genera, a field closely related to the history of identity and sexuality.

The historiography of gender has known a great development in the Anglo-Saxon countries, since the sixties of the twentieth century, and there are already classic works, such as, those of Sarah Pomeroy. We will not try now, as in any of the previous cases, to list them, not even briefly. Our purpose will be simply to indicate that the introduction of genera as a historiographical theme will also change the images of Classical culture understood as a paradigm.

It is evident that the woman as a genera is practically absent in the literary culture and political life of Classical antiquity. Leaving aside more or less exceptional figures in the literary field such as Sappho or some women who achieved political relevance, such as some Hellenistic queens or Roman empresses, it seems clear that the values on which Greek and Roman culture were built were mostly masculine, just as men were the main active subjects of political and social life.

Women in antiquity, like European women, were relegated by virtue of the so-called “sexual contract” to the domestic and private sphere, which resulted in them becoming passive subjects of historical events rather than protagonists; and consequently, they were practically absent from the works of Classical historians and from the development of European historiography until relatively recent times.

The history of the genera also represents another challenge to the images of the Classical tradition, since it possesses the same logic as that of the proposals of Marx, Nietzsche or Freud. Here, too, a hidden truth seems to be brought to light, thus revealing in a certain way the key to Classical history. It will no longer be a dominated social class, or a submerged continent (such as the Dionysphalic or the unconscious) that will now be brought to light; but the idea that more or less half of the human race had also been excluded from the discourse of history; that it could not find its meaning, in this case as in so many others, except from a negation of one of the basic components of social reality.

The development of the history of the genera is incomprehensible without the development of the feminist movement, just as Marxism is inseparable from certain political or trade union struggles. For this reason, the transformation of historiographical models was not only an intellectual process, but also a political and social process that would come into conflict with the socially and politically conservative ideology of most of the Classical philologists and historians of antiquity throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The figure of a woman may serve as an emblem of this process of social, political and intellectual transformations: Jane Ellen Harrison, professor of archaeology at the University of Cambridge and one of the first women who not only acceded to an academic position in England, but also made an important contribution to Classical studies, through works, such as, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, оr Themis. A Study on Social Origins of Greek Religion.

The life, the work and the social and political world in which Harrison lived form a unity that has been highlighted by her three biographers. Leaving aside her personal and family problems, analyzed by S. Peacock, it is clear that her access to Classical studies, or her conquest of a teaching position, were not easy, since Victorian values and academic and political prejudices were opposed to it. However, Harrison, once she achieved her goals, did not limit herself to reproducing the dominant discourse on the Greek world in England in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; on the contrary, she tried to renew its image through the study of archaeology and religion.

To try to do so, she set aside the image of mythology and Classical religion understood as aesthetic phenomena and applied different theoretical models borrowed from anthropology, sociology, or even psychoanalysis to try to understand Greek mythology and religion, first developing a theory, which would become famous, about the relationship between rite and myth, emphasizing the chronological and ontological priority of rite over myth. This priority allowed her to socially connect Greek religion and myth through a procedure that led her to seek the keys to the understanding of classical religions beyond the Greco-Roman world, broadening her horizon to all those peoples who in her time were being passive subjects of the process of colonization of the world; the so-called “primitive peoples.”

Comparing the Greeks with the “savages” may be more or less routine today, especially if we want to understand the most primitive stages of Greek history, but at the end of the 19th century it was a real heresy. It meant questioning the superiority of the ruling classes of the British Empire over its rulers and bracketing the superiority of Europe over the rest of the world.

Harrison’s reference to the primitive world was not only an attempt to contextualize some stories or mythological characters that were difficult to understand from the moment when the myth was no longer believed in, in Classical antiquity itself, and place them in social and historical contexts that could be similar, but also somehow more. If Harrison acted in this way, she was driven by an epistemological motive – it was a matter of explaining the similar by the similar.

But behind her epistemology, there was also an ideology and a moral proposal. The discovery of the irrational, the passionate and the primitive in Greece, already undertaken earlier by Nietzsche and Freud, is not only the discovery of a new world in the past, but also in the present. The liberation of Classical religion and mythology from the Classicist canon is the same process as the personal and social liberation of Harrison, who was forced into spinsterhood and solitude by academic and social conventions and who could not fully develop a full personal and social world because of her situation. For her, to liberate myth and to liberate Greece was the same as liberating herself and liberating the bourgeois society of late 19th century England.

The work of Harrison, together with that of Gilbert Murray and F. McDonald Cornford came to be known as the “Cambridge School” or “School of Myth and Ritual.” If I take it as a benchmark, it is because it contributed to change the image of the Classical world by making Greece and Rome lose their superiority over other historical cultures that may have been more or less similar to them, and by forcing Classical studies and ancient history to take into consideration the concepts and results of a social science whose development, which in the 19th century was parallel to history, was sometimes not very closely interrelated with these studies – namely, anthropology.

The rapprochement between ancient history and anthropology, carried out by different scholars in England, оr in France, by J. P. Vernant, M. Détienne and P. Vidal-Naquet, entails a risk of loss of identity of Classical studies for two reasons. Firstly, because it could dissolve them in the framework of a science of society in general and thus make them lose their supposedly proper categories (if they ever had them); and, secondly, because it establishes an equality before history between Eastern and Western peoples, primitive and civilized. This means putting aside the ethnocentric image on which these studies were built, as Martin Bernai has pointed out, and consequently making them to lose the privileged role they have been playing for centuries in the process of defining European identity. A role from which the cultivators of these studies benefited socially, through the social prestige that their cultivation carried with it.

After the decolonization of the world, a consequence of the Second World War, the boundaries between primitive and civilized, East and West, underwent a process of adjustment, which would partially lead to put all peoples on an equal footing. Perhaps because, as Ranke said, referring to Europe, all peoples are in history equally close before God.

At the present time, the Western world, on the contrary, seems to want to reaffirm its identity again vis-à-vis the East and the Third World, not unrelated to the attempt of some Classicists, such as Edward Luttwak or Victor David Hanson, to draw from ancient history lessons for contemporary politics, especially in the sense of reaffirming, as in Classical antiquity itself, the domination of minorities over the masses and of “superior” cultures over “inferior” ones. Naturally this would bring with it a retreat towards more historiographically conservative positions, returning to the social and political paradigm of Classicism and the abandonment of Marxist, gender or anthropological proposals. However, this will not be the case today in a clear-cut way, since ancient history and Classical studies are concretely structured as follows.

IV.

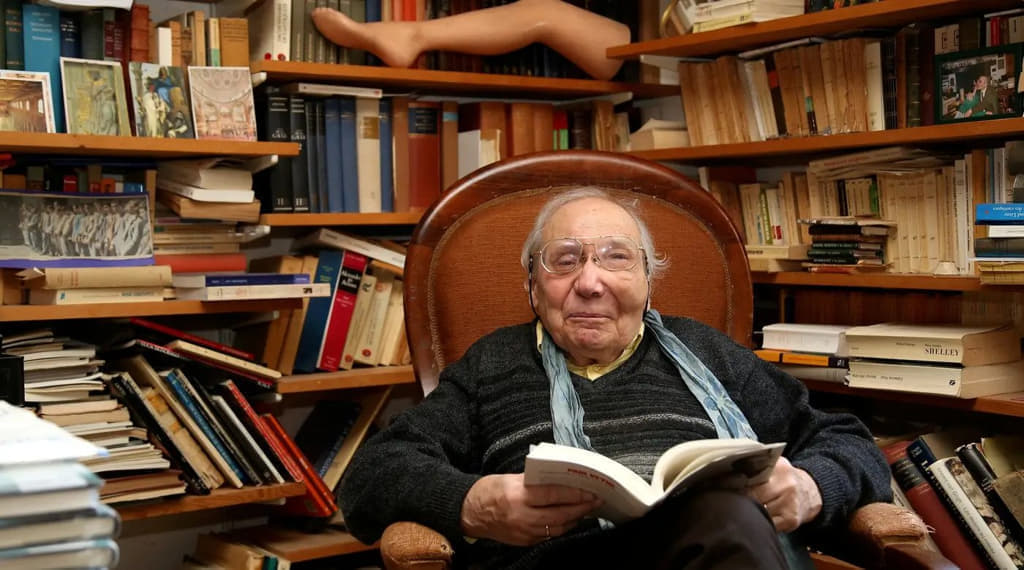

When writing about the history of historiography, it is common to allude to two types of circumstances that contribute greatly to explaining the genesis of the ideas of the great historians. First, their biographical circumstances are analyzed. Second, their political ideas, which on many occasions make up the essence of the thinking of the great historians, as Arnaldo Momigliano has masterfully taught us to see in his Contributi.

In spite of Momigliano’s undoubted prestige, many academic historians are reluctant about this type of studies, since they consider that the historian as such is a scientist and his political ideas should not condition his work, his personal circumstances being something that should be reduced to the personal or family sphere. If we want to understand the typology of Classical historians and philologists at the present time we must, we believe, follow Momigliano’s advice and also be guided by the recommendations of a philologist of antiquity, Friedrich Nietzsche, who in his The Untimely Meditations, carried out a masterly and still valid analysis of the figure of the Classical philologist and the contemporary European historian.

Nietzsche distinguished three types of historiography and historians, valid in 1873 and still today. Namely, the antiquarian historian, the monumental historian, and the critical historian. The antiquarian historian was and is defined as a professional historian. He is driven by his love for the past and his research is guided by the accuracy, thoroughness in the collection, preservation and reading of documents. This type of historian is very similar to the ancient collectors, studied by Krzystof Pomian. In the case of Classical studies, our historian is usually a philologist, a lover of texts, a faithful connoisseur and interpreter of Classical languages, who believes he has mastered the whole universe of the Altertumwissenchaften, the “Sciences of Antiquity,” so pompously called by the Germans. He, like Wilamowitz, masters everything from the most insignificant Greek language to the most sublime metaphysical ideas of Plato.

Similarly, if he is an archaeologist, numismatist or epigrapher, he carefully collects objects, coins or inscriptions, which he offers us in exhaustive catalogs. If he is not only an epigrapher but also a prosopographer, he will know the cursus honorum, senatorial or equestrian of the main personages of the Roman Empire, being aware of their careers and vicissitudes of life. In the same way, if he is an archaeologist, he will master the topography of ancient Rome, and of hundreds of other places.

All these scholars define themselves as “scientists.” They master a method that allows them to read, translate and interpret texts and documents from the past. And they do so objectively, dispassionately and faithfully. If we ask them about their ideology, they will tell us that, as scientists, they lack it. And even if they did have one, it would never interfere with their research. Their probity would not allow it in any way. They do not aspire to direct consciences. Their ideal of life is that of a secluded, almost monastic life, in which they like to relate to their colleagues, who are the ones who truly understand them and with whom they share their love of the past and of dead languages, languages whose cultivation is perhaps one of the few things that can allow us to become fully human.

Epistemologically they will define themselves as empiricists. They hate philosophy and speculation, because they are always attached to the positive, to the data, whose knowledge is the only thing that justifies the historian’s job. Politically they can be more or less conservative, but always discreet. Their natural place will always be the second piano. Their kingdom is apparently not of this world, although it really is. They will always be in favor of the established order. For them, as for Hegel, although always in a much more prosaic way, everything rational is real and everything real is rational. If something exists, it will exist for a reason; and that is precisely what we must learn from history; that the past and the present will always be justified. They are justified by their factual character. And if history teaches us anything, it is that a fact is a fact and that we must accept it as such. History is the realm of the contingent, but also of the necessary. That is what we have to learn from it as a science, that things are so, that the best we can do is to study them and consequently accept them.

The second type of historian is the monumental historian. In 1873-1876, this meant the nationalist historian; and today, it again means the nationalist historian; or, a few years ago, it meant the politically committed Marxist historian. This type of historian, on the contrary, does not aspire to isolate himself from the world, but to live in it. But not to live in it in any way, but to govern it. He is a historian who defines himself as an ideologist of the nation and as a discoverer of its essence. As a result, he aspires to social recognition of his merits and to be given a role in the direction of the nation or society. And if he knows the hidden things that make up the apparent reality, it is logical that he be the one who governs us. Plato said that if we want a pair of shoes we will go to a shoemaker; if we want to make a sea voyage, we will look for a good sea-captain; while if we are looking for who governs a city we resort to the vote, to the opinion, being wrong consequently.

For Plato, the one who should govern is the philosopher-king, since he is the one who knows the true nature of political things. In the contemporary world, from the birth of the nation-state in the 19th century, the one who claims for himself this role is the national historian who aspires not only to know the past and expose it in his books, but also to mobilize his compatriots by instilling in them enthusiasm for knowledge, and defense, if necessary, of their homeland.

This same mobilizing role was later assumed by the Marxist historian, also a connoisseur of the essence, of the hidden laws that regulate the march of societies and of history. It is this scientific knowledge, free of ideology that, from his commitment to the workers’ party, which allows the historian to place himself in the only valid observatory for the contemplation of historical reality, thus being consequently qualified to govern a country directly, when he is a political intellectual, like Lenin, or at least to guide the rulers. Although, in most of the cases, the numerous politicians simply imagined themselves as thinkers, with intellectual results that oscillated between the mediocre and the ridiculous. Just think of Ceaucescu.

The last type of historian is the critical historian, who, according to Nietzsche, does not place his life at the service of history, but places history at the service of life. For this historian, not everything is worthy of remembrance; after all, as Heidegger would later say, what is proper to the past is oblivion. We must free ourselves from the past, when the past is a weight that weighs upon us, when this weight consecrates everything that exists; and we must place the past at the service of life.

This type of historian is above all a more or less isolated intellectual. But if he becomes a solitary intellectual, it is not because that is his vocation or his preference, but he is forced by circumstances. His participation in this process of liberation must be both individual and collective. The historian writes оr speaks for someone; and that someone is his contemporaries, with whom he shares the world.

If we follow the terminology of Alfred Schutz, we could say that every historian lives, first of all, in an Umwelt environment, but is not isolated in it, but lives in it with his contemporaries, with his Mitwelt. In turn, this world derives from a previous world, Vorwelt, and will continue in a successive one, Folgerwelt. The historian must try to understand all these interrelated worlds, which should not necessarily mean that he must also justify them or be the main protagonist of their transformation.

If what he wants is simply to understand them, he may end up justifying them, just like the antiquarian historian. If he tries to change them too quickly, it could be that, reversing the sense of the Marxian thesis on Feurerbach, that his desire to change the world leads him to forget that he first had to study it. The fundamental thing in him must be to think that it is not possible to change the world, the outside, if one continues to think in the same way as the Vorwelt. The work of the historian is above all an intellectual work. His mission, like that of other intellectuals, is to try to think the world according to new concepts. However, this intellectual work will not be pure intellectual work. For, if we can learn anything from the history of historiography, it is that it has either kept pace with, or slightly lagged behind (sometimes by a lot) the transformations of social reality.

History is not an eternal science but a historical product. It is probably not even a science but something very close to the common sense of each culture, if it is only a form of storytelling. What is certain is that it is itself a historical product, and that, as such, it is in continuous transformation. Heidegger said that what defines temporality is precisely the future. The past as such no longer exists. The present can be reduced to the insignificance of the instant. Thus, if we can say that time exists, it is because there is still a future. Human life, as Ortega y Gasset said, is like a bow, which must always be taut. The moment it ceases to be taut life will come to an end.

For this reason, the work of the critical historian must consist, in 1872 and today, in helping to liberate individual and collective life by seeking and disseminating new ways of thinking about it, and thus contributing to its transformational process. This work will ensure that the study of history does not find its meaning in reference to the past, but paradoxically in reference to the future. Antiquity, that part of history which, precisely because of its own chronological scope, might seem more inaccurate, has, like no other stage of history, no meaning in itself. The sense it had is that of its protagonists, who are no longer alive. If we want to give it meaning, we can only act in two ways: either by glorifying it and thus consecrating the present, which will be conceived as its correlate, or by writing ancient history with an eye to the future, a future that will soon also be the past.

José Carlos Bermejo Barrera is Professor of Ancient History at the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). He has published numerous books in the fields of mythology and religions of classical antiquity and the philosophy of history. Among these are The Limits of Knowledge and the Limits of Science, Historia y Melancolía, El Gran Virus. Ensayo para una pandemia, and most recently, La política como impostura y las tinieblas de la información. He has published numerous works in academic journals, such as History and Theory; Quaderni di Storia, Dialogues d’Histoire Ancienne, Madrider Mitteilungen. He is a regular contributor to the daily press.

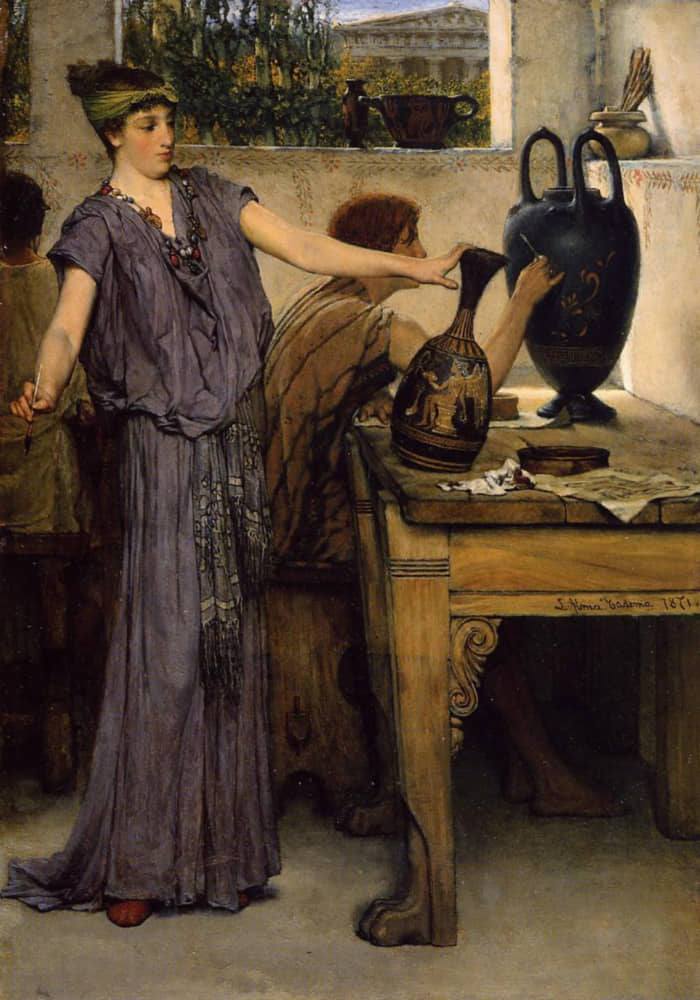

The featured image shows, “The Girl or the Vase,” by Henryk Siemiradzki; painted in 1887.