One of the most common objections to the belief that Jesus is the Son of God is the notion that he was a mythical figure, or that he was a real person but that the things he said and did were embellished or made up over time and He was “mythologized.” The “mythologized” argument is one of the most common scholarly atheistic objections to Christianity. In order to counter the idea that Jesus’ existence or His claim to be the Son of God was made up over the course of time, it is appropriate to see what some of the earliest non-Christian historians had to say about the existence of Jesus Christ and Christianity. Here we will take a look at four of the earliest non-Christian historians who mention Christ or Christians in their writings; Tacitus, Pliny the Younger, Suetonius and Josephus.

For a quick video explaining the essence of the historical writings quoted below in this article, please see:

One of the earliest known historians to write about Jesus was the Roman historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus (c. 55 – c. 117). Little is known of Tacitus’ life but much can be deduced from his writings and from the letters addressed to him by his intimate friend and historian Pliny the Younger.

The most influential part of Tacitus’ education took place during the initial part of Vespasian’s reign and it is possible that Tacitus, like his friend Pliny, was schooled in rhetoric by Quintilian, who under Vespasian was made the first public chair of Latin rhetoric at Rome. Although it is not known when Tacitus started his own political career, he did gain renown quickly as evidenced by a famous letter from his junior, Pliny.

Pliny stated that of all the eminent men then active, Tacitus seemed to be the worthiest of imitation. When writing about the burning of Rome during Nero’s reign, Tacitus mentions Christ and the Christians, in his work Annals (c. 115 – c. 116) where he states in book XV chapter 44:

“…But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the propitiations of the gods, did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their center and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired. Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car. Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed.”

The friend of Tacitus, Pliny the Younger, did not mention Jesus specifically in his writings, but he did mention the plight of the early Christians. Pliny was the Roman governor of Bithynia and Pontus (modern day Turkey) and, with respect to Christianity, he is famous for his letter to the Emperor Trajan around AD 112 asking counsel on how to deal with the early Christian community. His letter (X, 96) explains how Pliny had tried suspected Christians who were brought to trial before him. His letter asks for the Emperor’s guidance on how the Christians should be treated. The specific crime is not mentioned in the letter but the crime is most likely refusing to pray to the Roman gods.

Pliny details the practices of the Christians, stating, “But they declared their guilt or error was simply this—on a fixed day they used to meet before dawn and recite a hymn among themselves to Christ, as though he were a god. So far from binding themselves by oath to commit any crimes, they swore to keep from theft, robbery, adultery, breach of faith and not to deny any trust money deposited with them when called upon to deliver it. This ceremony over, they used to depart and meet again to take food—but it was of no special character, and entirely harmless.”

A possible acquaintance of Pliny was Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus who was another Roman historian that mentioned the Christians. He was probably born around AD 69 as deduced from his statement describing himself as a “young man,” twenty years after Nero’s death. Most scholars say his place of birth is Hippo Regius, a north African town in Numidia in modern day Algeria. He may have served on Pliny’s staff when Pliny was Proconsul of Bithynia and Pontus between 110 and 112. Under Trajan, he served as director of the Imperial archives. In his history concerning Nero (Nero 16), Suetonius describes Christianity as excessive religiosity and superstition (superstitio). When writing about the punishment of Christians he states: “Punishment was inflicted on the Christians, a class of men given to a new and mischievous [or ‘magical’] (maleficus) superstition.”

The fourth of these early non-Christian historians, Titus Flavius Josephus (37 – c. 100), like Tacitus, mentioned Christ explicitly. Josephus was born Yosef ben Matityahu in Jerusalem, which was then part of Roman Judæa, to a father of a priestly descent and a mother who claimed royal ancestry. He was a Romano-Jewish historian.

In Josephus’ Testimonium Flavianum (the testimony of Flavius Josephus) he writes a passage in Book 18, Chapter 3.3 of the Antiquities which describes the condemnation and crucifixion of Jesus by the Roman authorities. This passage is considered the most discussed passage of Josephus’ writings. Note in the passage below that Josephus writes “He was [the] Christ.”

Josephus states:

“Now there was about this time, Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man, for he was a doer of wonderful works, — a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews, and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ; and when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men among us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him, for he appeared to them alive again the third day, as the divine prophets had foretold these and the thousand other wonderful things concerning him; and the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day.”

The early non-Christian historians were important in documenting early Christianity. Even Eusebius, two centuries later, references Josephus in his History of the Church, Book I, stating:

“It was the forty-second year of Augustus’s reign, and the twenty-eighth after the subjugation of Egypt and the deaths of Antony and Cleopatra, the last of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt, when our Savior and Lord, Jesus Christ, at the time of the first registration, while Quirinius was governor of Syria, in accordance with the prophecies about Him, was born in Bethlehem, in Judaea. This registration in Quirinius’s time is mentioned also by the most famous of Hebrew historians, Flavius Josephus, who gives in addition an account of the Galilean sect which appeared on the scene at the same period, and to which our own Luke refers in the Acts …”

In his History of the Church, Eusebius also mentions Pliny the Younger in Book III.

“So great was the intensification of the persecution directed against us in many parts of the world at that time, that Plinius Secundus (Pliny the Younger), one of the most distinguished governors, was alarmed by the number of martyrs and sent a report to the emperor about the number of those who were being put to death for the faith. In the same dispatch he informed him that he understood they did nothing improper or illegal: all they did was to rise at dawn and hymn Christ as a god, to repudiate adultery, murder, and similar disgraceful crimes and in every way to conform to the law. Trajan’s response was to issue a decree that members of the Christian community were not to be hunted, but if met with were to be punished.”

From these four early non-Christian historians, writing about Christians or Christ and his claim to be the Son of God, we can conclude that there is plenty of evidence to support Jesus’ existence even outside of Holy Scripture and early Church Fathers’ writings about Jesus. These writings clearly show not only that Jesus existed as a historical figure but also that his followers professed him as the Christ and Son of God, and therefore this belief was not made up or “mythologized” years after he walked on the earth as fully human and fully God. The writings of Eusebius punctuate that fact, as he uses Josephus’s and Pliny’s histories as historical sources in his History of the Church, which he produced around AD 325, a full half-century before the canon of the Bible was closed.

Phillip Cuccia is a retired army officer, who served in armored and cavalry units, and then taught Military History at West Point, before joining the Army attaché corps, and serving in Italy at the U.S. Embassy in Rome. He has a Master’s degree in security studies from Sapienza University in Rome and a Master’s and Ph.D. in Napoleonic Studies from Florida State University. He currently teaches history for Liberty University. He established the Eusebius Society in 2019.

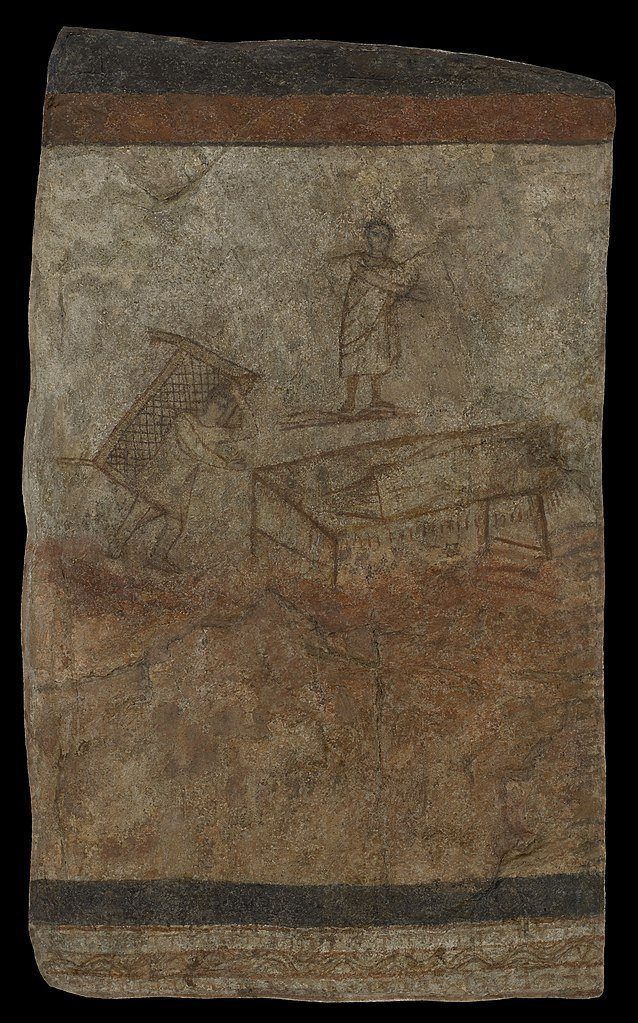

Featured image: Christ Healing the Paralytic. Baptistry, Dura-Europos, ca. 232 AD.