Directed by an Englishman who has not forgotten that Napoleon was his enemy, and who attacks his posterity through the means of propaganda—cinema—Ridley Scott’s film is heavy-handed to the point of ridiculousness. And it struggles, to say the least, to find its tone. The tragedy of the story eludes him, and some of the great protagonists are conspicuous by their absence. But why do we leave it to Hollywood to paint our great characters? And what is left of France after Napoleon? This article is both an analysis of the film and a more general historical reflection.

Expectations were high, but we were disappointed all the same. One might have imagined that Ridley Scott, a lover of history and blockbuster frescoes, would find the inspiration and form to tell the story of Napoleon, Emperor of the French. His first film, The Duelists, an adaptation of Conrad’s short story, set during the Empire, is as hard, incisive and sharp as steel, not to mention Gladiator, which regales us with sandy virile combat. Alien, Prometheus, Blade Runner; the list goes on and on.

The film’s main flaw is Ridley Scott himself: he is English. His entire film is an indictment of Napoleon. In his endeavor to demythologize and demystify the Emperor, a dazzling victor in the sunshine of Austerlitz, a grandiose force with the will of Destiny, romantic even in the fall of Waterloo, and the dark melancholy of St. Helena, Scott portrays an irascible little, fat man, traumatized by women and complexed by his mother, who to compensate for his weakness gets drunk on the blood of men, taking pleasure in killing. It is the kind of barroom psychology that would make Chateaubriand, the Emperor’s enemy biographer, pale, and Zweig, a portraitist in his own right, a surgeon of consciences and wills, feel sorry for him. The man’s flaws and failings are strung together like a string of bad apples: virile, toxic, macho, violent towards his wife, sexually obsessed, a pedophile, a liar, a narcissistic manipulator, a conspiracy theorist and an exaggerator. What the vulgar press lends to Donald Trump or Vladimir Putin is offered to us throughout. We start with the revolution, celebrated with the death of the Queen—the dark hours of our history—and end with a little moral lesson worthy of a Bertrand Tavernier thesis film: Napoleon is responsible for the death of millions of people, and he is revered as a legend.

The film’s tone is constantly ambiguous. Burlesque and self-mockery combine with the pathology of a killer’s itinerary. We have the worst of Nicolas Sarkozy, a nothingness on two feet. This is L’Histoire d’un mec meets Faites entrer l’accusé. Napoleon is sometimes ridiculous, sometimes as cold as a sociopath, sporting the same hard, constipated face under increasingly pasty features. This in-betweenness between farce and tragedy is uncomfortable throughout.

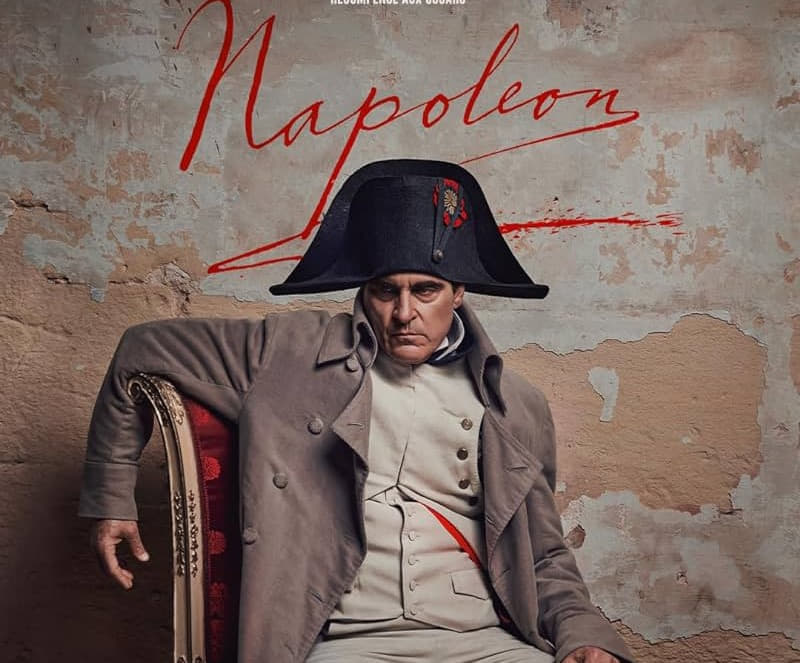

The film focuses solely on Napoleon and Josephine. Talleyrand is barely sketched in, Fouchet appears in a single shot, and Marshals Ney, Murat, Lannes and Masséna are nowhere to be seen. We can recall Claude Rich, John Malkovich and Guitry as the lame devil and our own Depardieu as Fouchet. The acting leaves much to be desired. Joaquin Phoenix can’t seem to get out of his role as the Joker, drawing mimicry, breathlessness and fragility from it. Both characters share common traits: an infirmity of the soul, a violence within them, a pathological coldness, a strange laugh and the behavior of a mental hospital escapee. It is hard to believe that the actor has remained locked into his role as a buffoon. Vanessa Kirby is unbearable, appearing disheveled all the time, bland and tasteless, laughing uncontrollably at the announcement of her divorce, sad as rain at Malmaison.

The relationship between the emperor and empress takes up a place that spoils the film. The viewer could not care less about this conflicted, friendly relationship; the passions that end up in ashes, the upscale domestic scenes in the Tuileries, to put it politely. No, the viewer could not care less. Scott has no idea how uninteresting the subject is. Napoleon, like all great figures in history, is solitary. To show him held, entrenched, locked in by his wife, is pathetic.

The chronological progression of events in the form of key dates is lazy. The Egyptian expedition is as uninteresting as it gets; and the Italian campaign, with the Pont d’Arcole and Marengo, is skipped. Jena, Wagram, Eylau, all three, are silent. The war in Spain does not exist. The campaigns in Germany and France are forgotten. All these disappointments fail to explain the geopolitical stakes of the moment. Napoleon was a pragmatic and deliberately authoritarian politician. His work as a reformer, too. So be it. What we are left with for over two hours is a distressing portrait of a mad, megalomaniac killer. As a backdrop, we would have preferred to see Napoleon in exile, in his last days, going over in his memory the important events of his life as Emperor, confronting his demons, introspecting his character, in the depths of his solitude and in the face of his intimate weakness.

But there is more to this film than meets the eye. The battle scenes, the ones that remain, are well realized. The assault on Toulon is dynamic, while Austerlitz, without sunshine or triumph, is shown in all its cruelty and violence. The death of those Austrian and Russian soldiers on that icy lake delivered to the cannonballs is implacable. Even Waterloo is not lacking in interest. The film’s cold, gray photography is chiseled; the sets, outfits and palaces are well laid out; the music, from Piaf to Haydn’s Creation, via a Mozarabic Kyrie Eleison played by Marcel Pérès, is welcome. The aesthetic side of this film does do the job, and lives up to its director’s reputation.

Do we really think that the Englishman Scott wanted to deconstruct Napoleon? This verb is often used to denounce a political attempt, driven by a certain ideology, to wipe the slate clean, to cancel, to destroy. I do not believe that the director is so committed to Wokeism as to ideologically undermine the Emperor. He reacts as a subject of perfidious Albion, France’s eternal enemy, and attacks his posterity through the means of propaganda: cinema. Yet to place the Emperor in a harsh light, to be on the other side, opposite, with those who suffered the Corsican ogre, is not entirely without interest if things had only been done well. The problem is, they are not. We did not wait for Scott to shoot Napoleon. Let us sting and provoke a little. Let’s play devil’s advocate.

Napoleon was the strongest armed force of his generation, and came at just the right moment to support the party of order. A leader was needed to avoid chaos and put things right. The bourgeoisie took power, replacing the old nobility, and chose its foal: Bonaparte, a man of action, a military man, a man of the center, neither revolutionary nor backward-looking. Napoleon was a man overtaken by the force of things he had taken on. His talent lay in his ability to synthesize the old and the new: royalism and the republican adventure inherited from Rousseau. Napoleon did not go backwards; he did not make a break; he made a synthesis that worked. If we were to be more provocative, we would dare say that Napoleon was the very product of that social mobility capable of bringing novices, parvenus and boors to the top. The late Ancien Régime was full of these energetic types, moving from chamber pot to chamber valet, from valet to minister, right up to the head of the Directoire.

Action française thinkers such as Bainville were not kind to La Paille au nez. Léon Daudet summed up their ideas on Napoleon in one phrase: “a crusade for nothing.” Yes, Napoleon meant twenty-two years of war (out of the fifty-one years of his existence) to protect France’s borders, respond to the aggression of Europe’s dynasties, impose a continental blockade against the English and a revolutionary ideal on the rest of Europe. While Napoleon’s gesture has greatness, and the sun of Austerlitz still burns every December 2 for over two hundred years, this perpetual war ravaged Europe. Napoleon slashed his map with a saber, closed abbeys and congregations, and abolished feudal systems in southern Germany; he abrogated the Holy Roman Empire; he plundered the whole of Italy, ravaging Venice, which saw its last doge. History forgives the victors and kills the vanquished twice. So much for the great European dream we have heard so much about! Behind the laurels of war, the living blood and the tears, these victorious battles, motivated by a confused maneuver to stifle the English, border on absurd glory. Scott ends his film with this assessment: three million men died in Europe on the battlefields. That is a lot. But as Henri IV’s marshal Montluc would say: “Lords and captains who lead men to death; for war is nothing else.” Napoleon is shown in caricatures pampered by the devil, playing cards and betting men, throwing up troops and cannons. He was a soldier who knew only perpetual war, enlarged an empire that had no geographical sense, and took it upon himself to oust Bourbon from the thrones of Europe.

Some have drawn a comparison, mutatis mutandis, with Adolf Hitler. Of course, the latter’s genocide and biological racism severely limit the comparisons that should be made. Notwithstanding these caveats, both were propelled by a well-defined social class, concerned with its economic interests in the face of the messy revolution, to replace the corrupt Directoire on the one hand, and the limp, dying Weimar Republic on the other. One became consul, the other chancellor; both for life. One became emperor and the other, Führer, took possession of all institutions. Both empires collapsed because they were based on war. For an empire to survive, you need to substitute economic peace for war, as the Romans understood. An empire whose only horizon is war is doomed to disappear quickly. Ten years for the first, twelve for the second. Foreign countries waged war against them. The war waged in Europe was waged against England. It was made possible by the general mobilization of youth, supported by a formidable demographic. The same thirst for power led them to open two fronts, in Western and Eastern Europe. Both went astray in Russia, suffering the invincible General Winter. The Grande Armée was broken, while the death of twenty million Russians broke the Wehrmacht. This Russian failure set in motion the mechanics of defeat and precipitated the collapse of both empires. If France was politically dead in 1815, Germany, which was already a ghost with Hitler, the ghost of a dead 1918, was completely reduced to zero and never really recovered.

Napoleon is partly responsible for our disenchantment. France was grandiose, then ceased to exist after Waterloo. I am one of those people who re-enact the battle a thousand times a year, cannot accept defeat and, in front of Scott’s film, could not watch this drama without bowing their heads in shame and sadness. With Waterloo, France was buried. I cannot deny that the defeat at Waterloo, which signaled our submission to foreign powers and those of money, was followed by a half-hearted Restoration, a bourgeois King of the French, a frilly Second Empire and a republic of bacchantes, rigid and progressive, and allowed for the worst of politics and its choices, but the best of literature and the blossoming of an astonishing painting of the salons. Waterloo, when did we become great? Under de Gaule, some would say, for a while, a little over a decade, and then some. Even now, we are still immersed in this malaise, this melancholy and this hope for greatness. We are waiting as some wait for the man who will save us. Our formidable paradox was revealed when the film was released: we are throwing up the man we are waiting for to emerge from his tomb at Les Invalides.

There was Abel Gance’s great film with the unforgettable Albert Dieudonné; later, by the same director, Austerlitz, with the serious and virile Pierre Mondy. Why on earth is no one in France capable of producing and directing, with substantial resources, a real film about the Emperor, while we leave the matter to those who are hostile to us? I would like to know.

Nicolas Kinosky is at the Centres des Analyses des Rhétoriques Religieuses de l’Antiquité and teaches Latin. This articles appears through the very kind courtesy La Nef.