On April 16, 1978, the famous French weekly, Le Nouvel Observateur, published an article by Michel Serres, philosopher and historian of science, with the now legendary title, “Do you know René Girard?” In it, the author presented Violence and the Sacred, the latest book published by a hitherto little-known French literary critic and university professor based in the United States. It was, according to Serres, a work called to illuminate the unfathomable abyss that surrounds the mystery of the foundation of human cultures. All of them are tombs and “Girard has long endeavored to decipher their tombstones.” Cain and Abel, Romulus and Remus, cities are created by men with their hands stained with innocent blood. Blood of brothers and also of strangers, those scapegoats whom myths and rites remember in the life-giving commemoration of the founding murder.

Violence is at the root of all institutions, but it is veiled, disguised by culture. By all cultures, except for one: “One culture, just one, is the exception and starts to uncover the secret. It starts to say that the victim of these murders is not responsible for all the evils. It starts shouting the innocence of Abel and Joseph. It is the Jewish culture…. The prophets are the first ethnologists. Girard dares to reopen Scripture, at the very moment when it is most forgotten, at the hour when to do so seems scandalous…. Read this clear, luminous, sacrilegious, calm book. You will have the impression of having changed your skin. You will crave, you will need peace…. With Darwin’s fire, remember, the old assemblages collapsed, everything was directed towards time, towards the general time of evolution, by means of operators of an unexpected simplicity. The same thing happens with Girard’s fire. We had not had a Darwin on the side of the human sciences. Here we have one.”

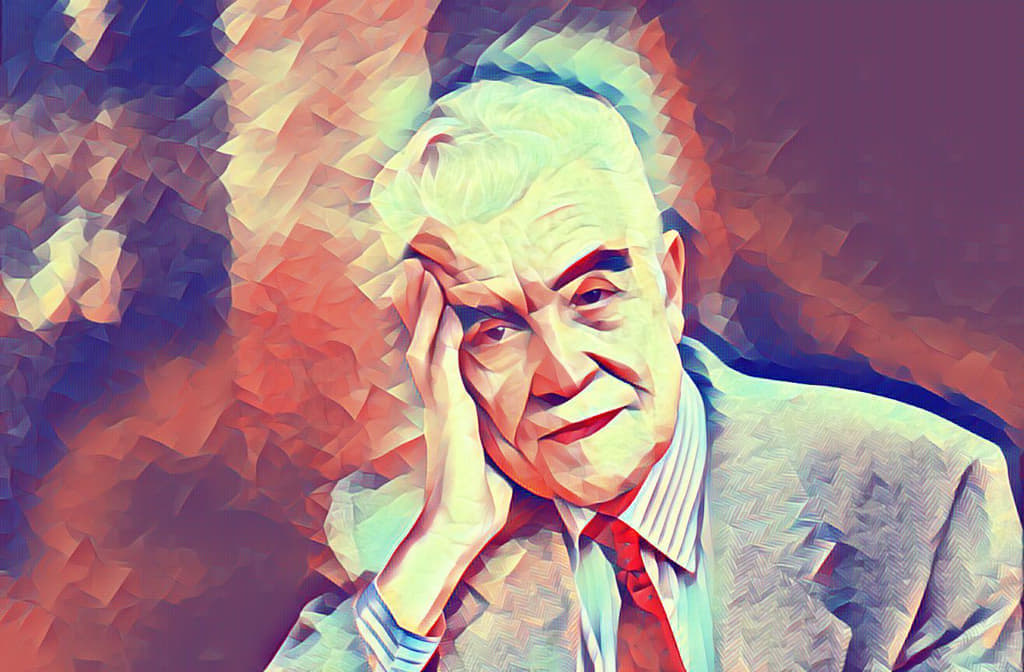

Isaiah Berlin, inspired by a proverb attributed to the Greek poet Archilochus, reminded us that there are two kinds of people: foxes and hedgehogs. The fox knows many things, while the hedgehog knows only one. December 25, 2023 will mark a century since the birth of one of the greatest hedgehogs of all time and perhaps the most significant of the 20th century. But Girard was a fascinating and uncomfortable hedgehog. Scorned by the intellectual clergy mimetically subjected to the fashions and jargons of the moment, whether those of existentialism or poststructuralism, ignored by the French academic establishment, he eventually came to be admired and repudiated for the same reason: for having had the audacity to propose an encompassing theory (from desire to religion to violence) at a time when every conception of the world of universal scope was deconstructed and destroyed by the sorcerers of suspicion. But Girard’s suspicion was even greater than the gregarious prejudice disguised as skepticism that came to proliferate among the buffoons of postmodernism.

As Xabier Pikaza has written, “Girard accepts and in a certain sense develops the anti-religious critique of the 19th-20th centuries: not only does he assume the attitude of the masters of suspicion, but he can take it to the end, without the risk of anthropological dissolution.” With Girard sounded the hour in which disbelieving reason dares to overcome the clichés and axioms of narrow rationalism and rigid positivism. The negation of Marx, Nietzsche and Freud was always partial, an intellectual epiphenomenon of the threatened bourgeois conscience, while Girard revolutionized our understanding of violence and built a new anthropological defense of Christianity. New because he began to listen anew to what many others only heard without paying real attention: what Girard once called “the ill-known voice of the real.” A voice silenced among myths and primitive rites but that resounds like a distant echo in the murmur of the Scriptures. It is the voice that changed the world forever.

There are thinkers who acquire the category of event because, as Francesc Torralba has written, after them the way of thinking is radically transformed. René Girard falls into this category. Jean-Marie Domenech called him the “Hegel of Christianity.” Pierre Chaunu called him the “Albert Einstein of the human sciences,” and Paul Ricoeur said of him that he would be as important for the 21st century as Marx or Freud were for the 20th. A sort of Guelph among the Ghibellines and Ghibelline among the Guelphs, Girard felt himself to be a disciple of Durkheim without renouncing the lineage of Pascal. An untenable position if ever there was one, but fertile as few others.

The Logos of Heraclitus versus the Logos of St. John, the violent message of the myths versus the love of the Gospel, the city of men versus the Civitas Dei. In Girard’s work, the same dynamism emerges, the same search is manifested, the same spiritual breath beats that beats in the heart of the doctor of Hippo. In any case, the Christianocentric turn of Girard’s work was the last scandal of a thought that developed book after book over five decades. It was a thought that reached the very Apocalypse along the path marked by the great classics of modern literature and anthropology. An unparalleled theoretical itinerary. “When I want to know the latest news, I read the Apocalypse.” Léon Bloy said it, but it was René Girard who took this sentence to the extreme of its theoretical possibilities in his work.

Benoït Chantre presides the Association des Recherches Mimétiques, a French research center dedicated to promote and disseminate studies related to the anthropological and social theory of René Girard. He is also the author of the first complete biography dedicated to the great French-American theorist (René Girard, Biographie. Grasset, 2023). It has been published, not by chance, in the year of the centenary of his birth. Because the task of writing the life of this singular thinker was long pending. An intellectual biography of almost twelve hundred pages that is supported by numerous unpublished texts and a rich correspondence. In them we discover the man behind the imposing mimetic theory, a theory he elaborated with the handwriting of Cervantes, Stendhal, Flaubert, James George Frazer, Durkheim, the prophets, St. John, St. Paul and Clausewitz. Between science and faith, the existential and intellectual journey of this authentic meteorite of Western thought who dared to bring together everything old and new in the long history of knowledge and learning.

Life of Girard

René Noël Théophile Girard was born in Avignon on Christmas Day, 1923. At a very young age, he passed the entrance exam to the Chartes School in 1942. Student in Paris during the Occupation, witness in Avignon of the American bombing of the city, the war left a deep mark on him. He was only 23 years old when he crossed the Atlantic. It was 1947 and he was unaware at the time that he would spend an entire academic career in the United States, a career that ended at the prestigious Stanford University. Girard, writes Chantre, lived on American campuses “like Hölderlin in his tower.” This exile to the American university, where researchers enjoy (or enjoyed) exceptional working conditions, was the opportunity of a lifetime. He did not miss it.

At the age of 38, he returned to the Christian faith, which he had lost during his adolescence. He had not set foot in a church since then. It was, as he often said, a conversion fruit of a grace mysteriously linked to his intellectual work. In his monumental Diccionario de pensadores cristianos (Dictionary of Christian Thinkers), Pikaza refers to Girard as “perhaps the most significant of the Christian converts of the 20th century.” For Hans Urs von Balthasar, one of the greatest theologians of the 20th century, “Girard’s project is certainly the one that today is presented to us with the greatest drama in soteriology and, in general, in theology itself.”

Much later, in 2005, in his eighties, Girard took Bossuet’s place at the Académie Française. The “fille aînée de l’Église” welcomed as an immortal of French letters the man who, in the words of the writer Roberto Calasso, should be described as “the last Father of the Church.” John Paul II, during his trip to France in 1980, asked the question: “France, first-born daughter of the Church, are you faithful to your baptism?” With Girard’s election to Chair 37 a discreet “yes” was heard within the old walls of the venerable institution founded by Cardinal Richelieu. However, Girard remained on the sidelines of the sterile ecclesiastical debates between progressives and conservatives, an epochal trifecta resulting from the globalization of the Church. The Avignon-born anthropologist could have agreed with Ernesto Sábato, who recalled this maxim of Schopenhauer: “Sometimes progress is reactionary and reaction is progressive.” This allowed Girard to place himself in a personal and singular way before the great themes of modernity and to cross the sinister century of ideologies and political religions, with their mental ties and their odious fanaticism, without paying any toll. For Michel Serres, Girard’s wager represented “the most fruitful hypothesis of the century.” His thought even inspired the homilies of Father Rainier Cantalamessa, preacher of the Pontifical Household since 1980, who recalled something that should not be forgotten regarding his work: “Many, unfortunately, continue to cite René Girard as the one who denounced the alliance between the sacred and violence, but they do not say a single word about the Girard who pointed out in the paschal mystery of Christ, the total and definitive rupture of that alliance.”

May this Christmas season more than any other bring us, with his first one hundred years of life, René Girard (1923-2015), always young and returning to us—for the work of this giant of the 20th century sealed forever that which his compatriot Georges Bernanos wrote: “It is not the Gospel that is old. It is we who are old.”

Domingo González Hernández holds a PhD in political philosophy from the Complutense University of Madrid. He is a professor at the University of Murcia. His recent book is René Girard, maestro cristiano de la sospecha (René Girard, Christian Teacher of Suspicion) He is also the Director of the podcast “La Caverna de Platón” for the newspaper La Razón. He has explored the political possibilities of Girardian mimetic theory in more than twenty studies and academic papers. His latest publication is “La monarquía sagrada y el origen de lo político: una hipótesis farmacológica” (“Sacred monarchy and the origin of politics: a pharmacological hypothesis”), Xiphias Gladius, 2020. This article appears through the kind courteesy of El Debate.