Exactly 100 years ago, in 1923, Carl Schmitt, a German lawyer whose controversial talent for brilliantly formulating political concepts continues to attract a great deal of attention from researchers to this day, published Roman Catholicism and Political Form. This book made him a prominent figure among German Catholic intellectuals in the Weimar Republic. Out of all the plethora of ideas in the 1923 essay, we would like to analyse Schmitt’s attitude to the Russian writer Dostoevsky, with whom he continuously polemicises not only throughout the essay, but it could be argued throughout his entire life. It would be of particular interest to us to compare Schmitt’s attitude to Dostoevsky and his heroes with the views of his contemporary and colleague, another German legal scholar Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy. Although these two authors took opposite stances in Germany in 1933 (support for the Nazi party and criticism of it from emigration), nonetheless they are united by the fact that, although they were jurists, they wrote about the Church, thus making them stand out from the general secular tendency of the social sciences of their era. As will be shown below, the Russian Orthodox author appears in the texts of these thinkers not so much in his capacity as a political-legal journalist, as in that of a vivid artistic symbol of a critical attitude to law and to the whole area of juridical thought and practice. Referring “to Dostoevsky” allows these philosopher-jurists to give their own diagnosis of the period following the First World War. This example makes it possible for us to trace the evolution of their own teachings, and their ideas on Russian culture and its place in world history.

1.

Emphasizing that non-Catholic authors are often motivated by “anti-Roman temper,” (Roman Catholicism and Political Form, 1996, p. 3) Carl Schmitt cites Dostoevsky as an example of this “temper” and his main opponent. He remarks that in the first centuries of the Reformation, the Protestants were the most striking bearers of this “temper,” but from the 18th century onwards Protestant political authors become increasingly rational in their anti-Roman argumentation. From Cromwell to Bismarck and the French secularists of the end of the 19th century a whole epoch passes; Catholic-Protestant polemic loses its emotional expressivity, and the sole exception to increasing political rationalism Schmitt finds in the Russian-Orthodox Dostoyevsky’s “portrayal of the Grand Inquisitor,” which allows: “the anti-Roman dread [to] appear once again as a secular force” (Ibid.).

Several pages later, Dostoevsky is once again mentioned by the German jurist in a typological group containing a paradoxically broad spectrum of political views: people who see in the Roman-Catholic Church the heir of the universalist program of the Roman Empire.

The Roman Catholic Church as an historical complex and administrative apparatus has perpetuated the universalism of the Roman Empire. French nationalists like Charles Maurras, German racial theorists like H[ouston] Stewart Chamberlain, German professors of liberal provenance like Max Weber, a Pan-Slavic poet and seer like Dostoyevsky—all base their interpretations on this continuity of the Catholic Church and the Roman Empire (5).

The principle of precedent in the evolution of law inspires Schmitt to an apology for the Roman Catholic Church as the bearer of a particular political and juridical mentality that has placed its seal on the juridical development of the peoples of continental Europe. The German jurist not only expresses his approval of Catholic political thought (where for him the most important author is the Spaniard Donoso Cortés), but also of the canon law which had adopted the ideas of dogmatic development of the First Vatican Council. Describing papal dogma in Max Weber’s categories of the juxtaposition of charisma and office, he sees in unilateral church authority the removal of the contradictions of parliamentarism in the ecclesial complexion oppositorum. The pope has a representative role or function as Vicar of Christ. The papacy is both institutional and personal, yet “independent of charisma” (Ibid., 14).

Noting different aspects of criticism of Catholicism, Schmitt singles Dostoevsky out among a special section of critics taking a position of anti-legalism as “pious Christians.” In his interpretation, the Russian writer comes close to the Protestant jurist Rudolf Sohm, a German historian of law known for his theory of the “lawless church.” Dostoevsky is interpreted by Schmitt through the prism of Sohm’s antagonism between the juridical and spiritual principles of church organization. Both Sohm and Dostoevsky, according to Schmitt, juxtapose their Christianity to the “ethos of power” of the Roman church, which is amplified to an “ethos of glory.” Such “pious” anti-Roman attacks, writes Schmitt, are dangerous because they not only subject church law and authority to criticism, but the very principles of form and rule of law in society, and thereby feed the anarchic tendencies.

Schmitt does not cite any extensive quotations from Dostoevsky; it is enough for him that the writer created the image of the Grand Inquisitor. This image is interpreted by the German jurist literally, outside literary convention, outside the problem of polyphony and authorship within the novel, The Brothers Karamazov, where “the poem of the Inquisitor” is narrated by Ivan Karamazov and commented on from an anti-Roman perspective by Alyosha Karamazov. In the perception of the German jurist, the Grand Inquisitor is almost a historical character, one of the highest prelates of the Catholic Church, a Spaniard, like the writer who was politically closest to Schmitt, Donoso Cortés. The Inquisitor operates within the framework of the Church’s judicial legal system and procedure among the subjects of the Spanish monarchy. As a result, all these political institutions are condemned and their authority undermined at the moment when Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor admits that he has succumbed to the temptations of Satan.

Thus, although Schmitt does not undertake a literary analysis of the text, he perceives it in all the depth of its artistic content. He sees in the figure of the Inquisitor a realistic image that demands a reaction from him (which may be regarded as an indirect recognition of the talent of the Russian writer). The German jurist is sure that the Inquisitor is right in the political dispute; he deliberately aligns himself on the side of the Grand Inquisitor, in opposition to Dostoevsky. Towards the end of his life, Schmitt stated in a conversation with Jacob Taubes, anyone who failed to see that the Grand Inquisitor was right had grasped neither what a Church was for, nor what Dostoevsky, contrary to his own conviction, had really conveyed (Jacob Taubes, Ad Carl Schmitt. Gegenstrebige Fügung, 1987, p. 15). For Schmitt, the Russian writer’s error consists in the fact that he depicts the Spanish prelate as a losing figure; he is placed by the narrative in a scandalous and unseemly, and therefore, one might say, satirical situation (the sort of Dostoevskian satire that Mikhail Bakhtin would term menippeia), which gives the lie to the exaltedness of his position. Where, through the use of irony, the sublime authority of the Catholic Church is undermined, for Schmitt the authority of jurisprudence is also undermined: after all, the latter has its origins in political Catholicism.

Owing to its formal superiority, jurisprudence can easily assume a posture similar to Catholicism with respect to alternating political forms, in that it can positively align itself with various power complexes, provided there is a sufficient minimum of form “to establish order”…Once the new situation permits recognition of an authority, it provides the groundwork for jurisprudence—the concrete foundation for a substantive form (29-30).

Schmitt attributes “potential atheism” to Dostoevsky (as if the writer projects his own potential atheism onto the Roman Catholic Church), because he sees in him an “anarchic instinct.” For Schmitt, the anarchist is essentially atheistic, because he denies the possibility of authority. The romantic reader perceives the institutional coldness of Catholicism as evil, and the formless breadth of Dostoevsky as true Christianity; but this is a false contrast.

All this leads Schmitt to the conclusion that, for all the apparent differences between Dostoevsky and the Bolsheviks (the latter he initially conflates with “American financiers” in their rejection of classical jurisprudence), they represent a single stream of anarchist sentiment opposed to classical politics and the Western European legal tradition. And despite the phrase, “I know there may be more Christianity in the Russian hatred of Western European culture than in liberalism and German Marxism… I know this formlessness may contain the potential for a new form” (38), Schmitt’s condemnation of Dostoevsky remains in force: he is a symbol of the barbaric Russian threat to European forms, both cultural and legal. The German jurist interprets him anarchically in almost the same way that the French existentialists would later do, and it is this interpretation that he himself condemns as the threat of “potential atheism.” In the final part of the essay, where Schmitt retells the dispute between the Russian and Italian revolutionaries Mikhail Bakunin and Giuseppe Mazzini, the image of the Grand Inquisitor created by Dostoevsky must inevitably join the “Bakuninist” line of argument in the European revolutionary movement, as for Schmitt Russian thought is a priori anarchist.

2.

The German-American jurist, historian, and social thinker Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy who was in contact with Carl Schmitt until 1933 wrote about Dostoevsky in the context of the Russian Revolution and its new order (Wayne Cristaudo, Religion, Redemption and Revolution: The New Speech Thinking of Franz Rosenzweig and Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, 2012). “Dostoevsky extricates the types of men who will become the standard bearers of the Revolution. To read Dostoevsky is to read the psychic history of the Russian Revolution” (Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, Out of Revolution, 1938, p. 91).

Rosenstock-Huessy created his theory of revolution after the First World War. The son of a Berlin banker from a Jewish family, as a young man Eugen chose to be baptized into the Lutheran Church. In 1912, at the age of 24, he became Germany’s youngest associate professor as a teacher of constitutional law and legal history at the University of Leipzig, where he worked with Rudolf Sohm. During the war, Rosenstock-Huessy was an officer in the German army at Verdun, and after demobilization he returned to academic and social activities. During the war itself, he became one of the organizers of the Patmos Circle, a group of intellectuals who gathered to reflect on the catastrophe of the world war. The Patmos Circle included, in addition to Rosenstock-Huessy, such well-known intellectuals as Hans and Rudolf Ehrenberg, Werner Picht, Victor von Weizsäcker, Leo Weismantel, Karl Barth, Martin Buber, and Franz Rosenzweig, among others. From 1915 to 1923, due to the crisis of European culture, the founders of this circle felt themselves to be living in a kind of internal immigration “on Patmos” (hence the publishing house they founded in 1919 was named Patmos).

Rosenstock-Huessy saw the Russian Revolution as the last possible European revolution, completing a single 900-year period of humanity’s quest in the second millennium. This period begins with the revolution of the Roman Catholic Church under the authority of the papacy against the power of monarchs and feudal overlords. Subsequently, the “chain of revolutions” was continued by the Reformation in Germany, the Puritan Revolution in England, the American Revolution, the French Revolution and, finally, the Russian Revolution. As a result, the Russian Revolution is part of the autobiography of every European.

Returning to Dostoevsky, it must be said that Rosenstock-Huessy emphasizes his dual identity as both a Russian and a European writer, who so virtuoso-like masters the Western European form of the novel that he cannot in any way be a symbol of “formlessness.” Russian novels became part of European culture in a special political period.

In the sixties, after the emancipation of the peasants, when the split between official Czarism and the Intelligentsia had become final, when the revolutionary youth vanished from the surface and sank into the people, the soul of old Little Russia began to expire. But some poets caught the sigh. Through their voice and through the atmosphere created in their writings, Russia could still breathe between 1870 and 1914. This literature, by being highly representative in a revolutionized world, became the contribution of Russia to the rest of the world. Without Dostoevsky and Tolstoi, Western Europe would not know what man really is. These Russian writers, using the Western forms of the novel, gave back to the West a knowledge of the human soul which makes all French, English and German literature wither in comparison (91).

The people Dostoevsky describes are not the heroes of Romanticism, distinguished by their special talents; on the contrary, “they are as dirty, as weak and as horrible as humanity itself, but they are as highly explosive, too. The homeless soul is the hero of Dostoevsky, the nomadic soul” (Ibid.).

For Rosenstock-Huessy, however, the “dynamite man” of Dostoevsky’s novels is not only a destroyer of law and order, living in an atmosphere of permanent scandal, but also a potential figure of the future. This is exactly the type of figure needed in the new circumstances of the twentieth century, when economic disasters and wars have become part of everyday life. “The revolutionary element will become a daily neighbour of our life, just as dynamite, the explosive invention of Nobel, became a blessing to contractors and the mining industry” (93).

The world of Dostoevsky’s novels is a world in which human passions, “the reverse of all our creative power… are faced without the fury of the moralist, or the indifference of the anatomist, but with a glowing passion of solidarity in our short-comings. The revolutionary pure and simple is bodied forth in these novels as an eternal form of mankind” (Ibid.).

Thus, Rosenstock-Huessy notes in the political idea of the Russian Revolution, as reflected in nineteenth-century Russian literature, precisely what Schmitt denies to the “Russians”: form. The Russian Revolution not only criticized the system of law created by the previous epoch (primarily the French Revolution, which in its drawn-out century-long cycle found a modus vivendi with the Anglo-American world), but also critically cleared the space for a new phase of world history: the planetary international organization of humanity.

Rosenstock-Huessy takes the contribution of the Catholic Church to the legal tradition of Europe extremely seriously, and in this he coincides with Schmitt. However, the Catholic idea is not the only one at the origin of the Western tradition of law, according to the German-American jurist. To no lesser extent, this tradition is the result of another religious revolution—that of Martin Luther—and the entire Protestant Reformation that followed. Therefore, those in the ranks of Hitler’s supporters who try to idealize the “Roman form” in modern times deny the achievements of the Reformation, and the Führer becomes for them a kind of “false pope.” The Russian situation, in which Dostoevsky’s heroes find themselves, is certainly different. Rosenstock-Huessy notes that the Russians were the first non-Roman (in the ecclesiastical sense) nation to launch a revolution of world significance, and that the Russian Church stands apart from and outside the Catholic-Protestant clash.

In Russia the Church had never conquered its liberty from the Empire. It had been petrified for a thousand years. Nothing had moved within the Church since the famous monasteries of Mount Athos were founded during the tenth century… These traditions were well-preserved in Russia. The Russian church, it is true, kept all the joy and delightful cheerfulness of ancient Christianity, and since there was less struggle with popes or reformers or puritans, it upheld the old tradition much better than Western Christendom. The childlike joy and glee which the members of the Russian and Greek Church feel and express at Easter are strange for a Roman Catholic, to say nothing of a Protestant (42).

Behind these words of a loyal Lutheran is not so much praise as a statement of fact, a clarification of the details of a historical drama. The German-American social thinker believes that the Russian church, “having lost to the empire,” is under attack by the Bolsheviks not because it poses a threat to them as part of the old order, the “ancien régime,” like the Catholic Church during the French Revolution. On the contrary, from the Bolshevik point of view, it is to be destroyed because, as it stands, it is a symbol of weakness, a symbol of peasant Russia, “the Church of the ‘moujik.’”

To the Russian Moujik the church gave one special instrument of communication with the majestic world of God and his Saints, an instrument well adapted to a far-off village in the country. In the lowlands of the Volga, earth is expanding and the individual is quite lost. Man is, in Russia, but a blade of grass. To this powerless man the church presented the Ikons, the painted images of the Saints… The Saints visited the poor as witnesses of a united Christianity far away, and as sponsors of a stream’ of power and strength going on from time eternal (42-43).

The Soviets must be against the Ikons because these reflect village economy… that fight is connected with the industrialization of Russia (44).

Rosenstock-Huessy refers to the church tradition of the Russians not as national, but as the preserved universal tradition of the first millennium: “In Russia in 1914, and in Russia only, the Christian Church was still what it had been everywhere in 900” (44).

Nationalism is a concept that for Russians is not connected with the traditional church, but rather with their openness to Europe in the 19th century: “capitalism presented itself to their eyes in the form of fervent nationalism… Furthermore, all the western territories of the Empire, Poland, the Baltic provinces, were more national than Russia itself” (66).

Returning to Dostoevsky, we can say that his ideal, which he puts into the mouth of Elder Zosima (“the state having become the church”) is not anarchy, but form, order, structure—a “church-like order,” as Rosenstock-Huessy calls it. And to the extent that this ideal is ecclesiastical, it is at the same time culturally a conduit of the classical culture of Roman antiquity. Dostoevsky’s political ideal, expressed through Elder Zosima, is not related to the nation-building of the “Russians;” it is universal, and yet it is an ideal of social and political form, not anarchy. The form of social life that Dostoevsky would like to see is as distanced as possible both from political romanticism and romantic nationalism in the style of J. G. Herder. Romantics might be defined as those who, in the age of the Great Reforms, would have liked to see the liberation of the individual in judicial and peasant reforms or in the mechanical destruction of czarism, and it is their dreams that Dostoevsky dispels in his works.

Thus, Rosenstock-Huessy, unlike Schmitt, does not ascribe anarchist sympathies and “anti-Roman temper” to Dostoevsky (and Russians in general). The German-American thinker scrutinizes the cultural preconditions of the Russian Revolution and concludes that many aspects of the anti-legalism of Russian authors are a criticism of the liberal-bourgeois law of Western European countries. The question of how law and religion will be treated in post-Bolshevik Russia for Rosenstock-Huessy remains open.

Conclusion

Having considered the juridical ideas of Carl Schmitt and Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, which they expressed in the form of comments or references to Dostoevsky and the images of his heroes in the 1920s-30s, the following conclusions can be drawn. Dostoevsky’s heroes are certainly a symbol of anti-juridical existence, both for Carl Schmitt and Rosenstock-Huessy, but their interpretation of this symbolic space differs. Schmitt insists on the anarchism inherent in Russian culture, but his attitude towards the image of the Grand Inquisitor is complex. He solidarizes with him, writes about his political correctness, but at the same time he believes that Dostoevsky, due to his attitude as an Orthodox Christian towards a Roman Catholic, was fundamentally wrong and biased in depicting the Spanish prelate as an object of satire in a scandalous situation. As a result of this, the Inquisitor cannot symbolize a solution to the problem of the authority of law. The problem with this image, Schmitt suggests, is that it is written by an author for whom Christianity is infinitely broad and formless.

Rosenstock-Huessy argues that Dostoevsky anticipated and described the human type of the Russian revolutionary. While remaining critical of Marxism, and to an even greater extent of Bolshevism, the Protestant thinker notes in the political idea of the Russian Revolution the positive content of social justice reforms. Dostoevsky’s heroes have “explosive power” and criticize the social and legal order of previous epochs (the French and English revolutions). However, this criticism, even passing through tragic errors, clears the space for a new cooperation of Christian forces in the context of a new universal planetary phase of human history.

Irina Borshch is a historian of legal thought. She is also a doctoral researcher at the Waldensian Faculty of Theology (Rome) and a senior fellow in the Ecclesiatical Institutions Research Laboratory at St. Tikhon’s Orthodox University (Moscow). She holds a Doctorate in Missiology from the Pontifical Urbaniana University.

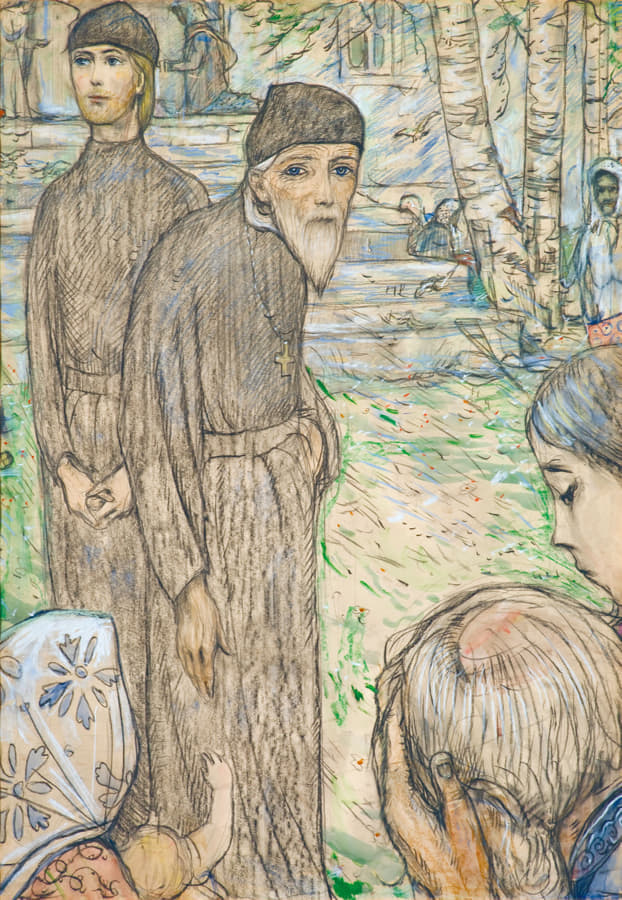

Featured: Elder Zosima, by Ilya Glazunov; painted in 1982.