Part 1. A Brief History of Chaos: from Ancient Greece to the Postmodern

The Chaos Factor in the U.S.S.R.

The most thoughtful observers of the Ukrainian front note the peculiar nature of this war: the chaos factor has increased enormously. This applies to all sides of the Special Military Operation, both to the actions and strategies of the enemy and our command, as well as to the dramatically increased role of technology (all kinds of drones and UAVs), and the intensive online information support, where it is almost impossible to distinguish the fictitious from the real. This is a war of chaos. It is time to revisit this fundamental concept.

Chaos for the Greeks

Since the word—χάος—is Greek, then its meaning must also be originally Greek, related to semantics and myth, and hence to philosophy.

The very root meaning of the word “chaos” is “to gape,” “to yawn,” that is, an empty place that is localized between two poles—most often between Heaven and Earth. Sometimes (in Hesiod) between the Earth and Tartarus, that is, the area under hell (Hades, aedes).

Between Heaven and Earth is air, so in some later systems of natural philosophy chaos is identified with air.

In this sense, chaos represents an as yet unstructured territory of relations between ontological and further cosmogonic polarities. It is in the place of chaos that order appears (the original meaning of the word κόσμος is beauty, harmony, orderliness). Order is a structured relationship between polarities.

Erotic-Psychic Cosmos

In myth, Eros and/or Psyche appear (become, arise) in the territory previously occupied by chaos. Eros is the son of fullness (Poros, Heaven) and poverty (Penia, Earth) in Plato’s Pyrrho. Eros connects opposites and separates them. Likewise, Psyche, the soul, is between the mind, the spirit, on the one hand, and the body, matter, on the other. They come to the place where chaos reigned before, and it disappears, recedes, pales, pierced by the rays of a new structure. It is the structure of an erotic—psychic—order.

Thus, chaos is the antithesis of love and soul. Chaos reigns where there is no love. But at the same time, it is in place of chaos—in the same zone of existence—that the cosmos is born. Therefore, there is both a semantic contradiction and topological affinity between chaos and its antipodes—order, Eros, and the soul. They occupy the same place—the place between. Daria has called this area the “metaphysical frontier” and has thematized it in different horizons in her recent writings and speeches. Between one and the other there is a “gray area” in which to look for the roots of any structure. This is what Nietzsche meant, that “only he who carries chaos in his soul is capable of giving birth to a dancing star.” The star in Plato, and later in many others, is the most contrasting symbol of the human soul.

Chaos in Ovid

The second meaning, which can already be guessed from the Greeks, but which is not too strictly described by them, is found in Ovid. In the Metamorphoses he defines chaos through the following terms—a rough and undivided mass (rudis indigestaque moles), consisting of poorly combined, warring seeds of things (non bene iunctarum discordia semina rerum), having no other property than inert gravity (nec quicquam nisi pondus iners). This definition is much closer to Plato’s χόρα, “the receptacle of becoming,” than to the original chaos, and resonates with the notion of matter. It is the mixing of the elements that is emphasized in such chaotic matter. This too is the antithesis of order and harmony; hence Ovid’s Discordia-enmity, which refers back to Empedocles and his cycles of love (φιλότης)/war, enmity (νεῖκος). Chaos as enmity is again opposed to love, φιλία. But here the emphasis is not on emptiness, but on the contrary, on the ultimate, but meaningless, unorganized fullness—hence Ovid’s “inert gravity.”

The Greek and Greco-Roman meanings equally oppose chaos to order, but they do so differently. Initially (with the early Greeks), it is rather a void as light as air, whose sinister character is revealed in the gaping mouth of an attacking lion or in the contemplation of a bottomless abyss. In Roman Hellenism, the property of gravity and mingling comes to the fore. Rather than air, it is water, or even black and red boiling volcanic lava.

Chaos at the Origin of Cosmogony

From this instance, chaos, begins the cosmogony and sometimes theogony of Greco-Roman religion. God creates order out of chaos. Chaos is primordial. But God is more primal. And he arranges the universe between himself and not himself at all. After all, if God is an eternal affirmation, you can have an eternal negation. There can be two kinds of relationship between the two—either chaos or order. The sequence can be either—if it’s chaos now, there will be order in the future. If there is order now, it will probably deteriorate in the future and the world will descend into chaos. And then again God will establish order. And thus, a period of time. Hence the theory of cosmic cycles, clearly stated in the Statesman by Plato, but most fully developed in Hinduism and Buddhism. Hence, Empedocles’ continually alternating eras of war/love.

Hesiod’s cosmogony begins with chaos. In [the theogony of] Pherecydes of Syros, it begins with order (Zas, Zeus). Time can be counted down from morning like the Iranians, or from evening like the Semites. Chaos is not opposed to God. It is opposed to God’s world.

As long as there is no order, the earth does not know that it is earth. For no distance has been established. And so, she merges with chaos. Earth becomes Earth when Heaven proposes to her and gives her a wedding veil. It is the cosmos, the ornament behind which chaos hides. So, it is with Pherecydes, in his charmingly patriarchal philosophical myth.

Chaos of the Golden Age

Plato’s late dialogue the Statesman gives a description of the phases of the history of the cosmos, where we can recognize two types of chaos, the initial and the final.

The first phase is described by Plato as the reign of Kronos. Its peculiarity is that the Godhead is inside the world, immanent to it. In this period all processes unfold in the opposite direction to the usual. The sun rises in the west and sets in the east. People are born out of the earth as adults and only grow younger with time, until they become a drop of seed and disappear into the earth. The sexes do not exist—all are androgynous.

This state can be partly correlated with chaos, but only with the primordial, in which order is implicit in the form of the immanent presence of the Divine. This is the “chaos” of the golden age. Some details of Plato’s account of Kronos’ reign can be correlated with Empedocles‘ fanciful description of the cosmic age of discord, but in Plato the reign of Kronos is presented, in contrast, as a time of peace and contemplation—androgyny is engaged in philosophy.

The Transcendental Order

The second phase is the reign of Zeus. Here the relationship between God (the Nurturer) and the cosmos changes. Zeus is removed to an “observation point” (περιωπή), a “watchtower” on the other side of the cosmos. God is now transcendent to the world, not immanent to it as under Cronus.

Plato describes it this way: “In the fulness of time, when the change was to take place, and the earth-born race had all perished, and every soul had completed its proper cycle of births and been sown in the earth her appointed number of times, the pilot of the universe let the helm go, and retired to his place of view; and then Fate and innate desire reversed the motion of the world” (Statesman, 485).

Order henceforth ceases to be implicit, dissolved in the cosmic environment itself, and becomes explicit. Zeus is the judge. He, by virtue of his distance from the cosmos, distinguishes when the cosmos and humanity behave harmoniously and according to the law and when they deviate from it.

Zeus’ reign is in turn divided into two periods. In the first, the cosmos is oriented toward Zeus, imitates him, follows his instructions and precepts. This forms the order—the one we know. The sun rises in the east and sets in the west. People are henceforth divided into two sexes, male and female. Here we can recall Aristophanes’ story from another dialogue, Symposium, which deals with the dissection of androgynes who rose in rebellion against the gods. Conception, fetal maturation, birth, and adulthood take place in the usual order. Exhausted old men die and are buried in the ground.

Final Chaos: Late Antiquity

Gradually, however, the cosmos, left to itself, loses its resemblance to the Divine, forgets its instructions, and begins to move on its own volition in an uncertain direction.

Plato describes it this way: “Now as long as the world was nurturing the animals within itself under the guidance of the Pilot, it produced little evil and great good; but in becoming separated from him it always got on most excellently during the time immediately after it was let go, but as time went on and it grew forgetful, the ancient condition of disorder prevailed more and more and towards the end of the time reached its height, and the universe, mingling but little good with much of the opposite sort, was in danger of destruction for itself and those within it” (Statesman, 273).

It is important that Plato here uses the expression “ancient condition of disorder” (παλαιά ἀναρμοστία), although in this myth itself there was no disorder at the beginning of cosmic unfoldment (Kronos’ kingdom). “Antiquity” here is placed not on the time scale but in a logical topology and indicates the primordiality of the emptiness “preceding” the origin of the world. The fall into the “pathos of ancient disharmony” (τὸ τῆς παλαιᾶς ἀναρμοστίας πάθος) is due to oblivion (λήθη). But oblivion, is opposed to memory, which is the reference to something meaningful in the past. Memory is the memory of Zeus and even of the much older periods of Kronos’ reign, where the original philosophy—the prisca theologia of the Florentine Neoplatonists—originated. Chaos is ancient, not because it represents something very early. On the contrary, it arises precisely when memory is shortened, if not erased altogether. In some sense, such chaos is something new and even the newest. It appears precisely at the end of the world. It is the ultimate chaos. It triumphs precisely when the content of the history of existence fades.

After the cosmos, left to itself, finally collapses (which means that order exists only when it is oriented toward something higher than itself, toward Deity, while by itself, taken purely immanently, it is sooner or later doomed to an imminent fall), the Provider, in mercy, reproduces it again. And everything repeats again—the sun rises again in the west, men are born from the earth asexual, etc. (These images remarkably resemble some of the details in the description of the resurrection of the dead and the Last Judgment in Christianity and monotheistic traditions, as well as in Zoroastrianism).

It is important for us that the “ancient chaos” in this picture comes at the end of Zeus’ reign; that is, after order has collapsed. Such chaos, therefore, is final. It arises precisely because of the loss of memory of the eternal; that is, of the even more ancient than chaos itself. In the final chaos, antiquity is erased. Therefore, it becomes pure becoming; the ephemerality of the present, ready to collapse into an already completely meaningless future. Such a future never arrives, constantly slipping away, leaving only the recursive absurdity that repeatedly reproduces itself.

The truly initial chaos is opposed to this ultimate chaos. Initial chaos is closer to the very first version of its Greek interpretation: a void not yet filled with order, hierarchy, a vertical structure. It lacks materiality, density, mixing and resistance. It is as transparent and permeable as pure air.

The ultimate chaos, on the other hand, is reminiscent of Ovid’s chaos. The remains of order are mixed in it; such chaos is residual. It follows order when order no longer exists. The final chaos is murky, filled with the senseless jostling of bodies (which Plotinus hated so much). It resists any creative impulse.

At the moment of cosmic midnight, there is a transubstantiation of chaos—the final chaos turns into the initial chaos.

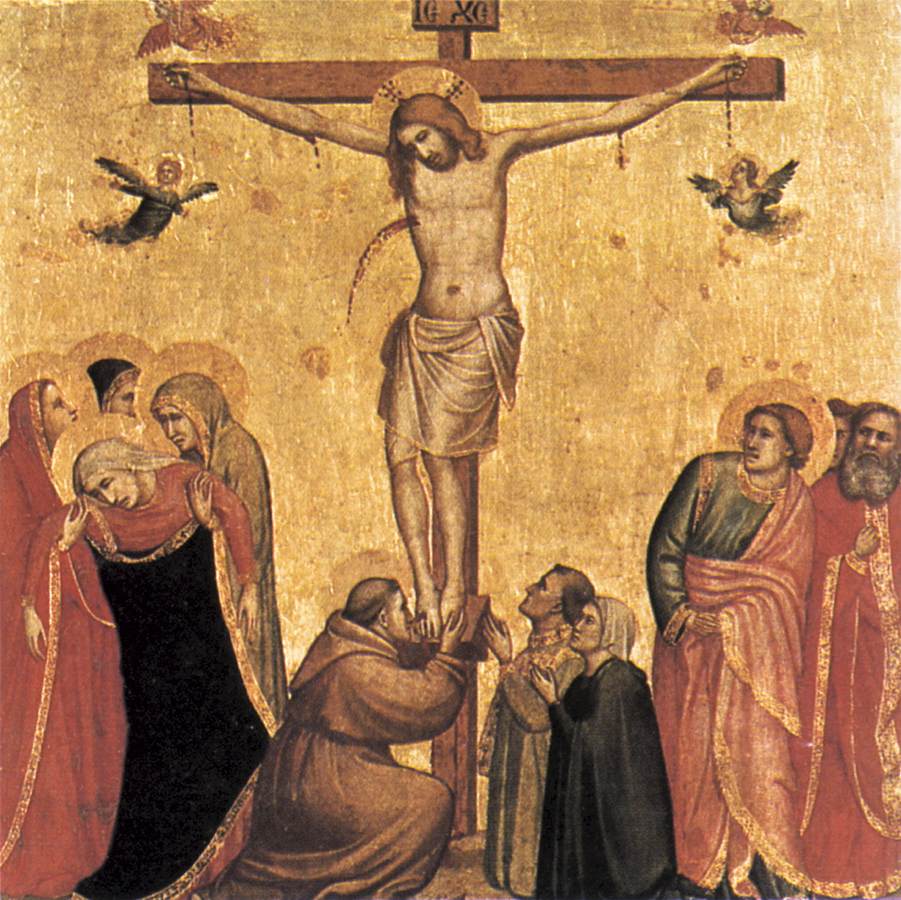

The Disappearance of Chaos in Christianity—But tohu wa-bohu

In Christianity, chaos disappears. Christianity knows only one God and His creation; that is, order, peace. Once upon a time “the earth was sightless and empty, and darkness over the abyss” (תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ וְחֹ֖שֶׁךְ עַל-פְּנֵ֣י תְהֹ֑ום ). The Hebrew term tohu means precisely emptiness, absence, and fits well with the Greek concept of chaos. Already in this phrase, with which the first section of the Old Testament begins, tohu is mentioned twice, which is completely lost in the translation—the first time it is rendered “without sight,” and the second time in the plural (עַל-פְּנֵ֣י תְהֹ֑ום) in the combination “over the void,” literally “over the face of tohu“). The word bohu (בֹ֔הוּ) in the combination tohu wa-bohu (תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ) is no longer used in the Bible (except Isaiah 34:11), which simply quotes the expression from the beginning of Genesis. Thus literally “the earth was chaos and ?, and darkness (hsd) over the face of chaos (or in the face of chaos).” In the Greek sense, we could say that “the earth was hidden by chaos,” which made it impossible to see (by Heaven, created in the first line of Genesis) that the earth was the earth.

Here God creates clearly not out of chaos, but out of nothingness. And he creates at once the light spirit (Heaven) and the dark flesh (Earth). Chaos is what is between them; what hides their true relationship.

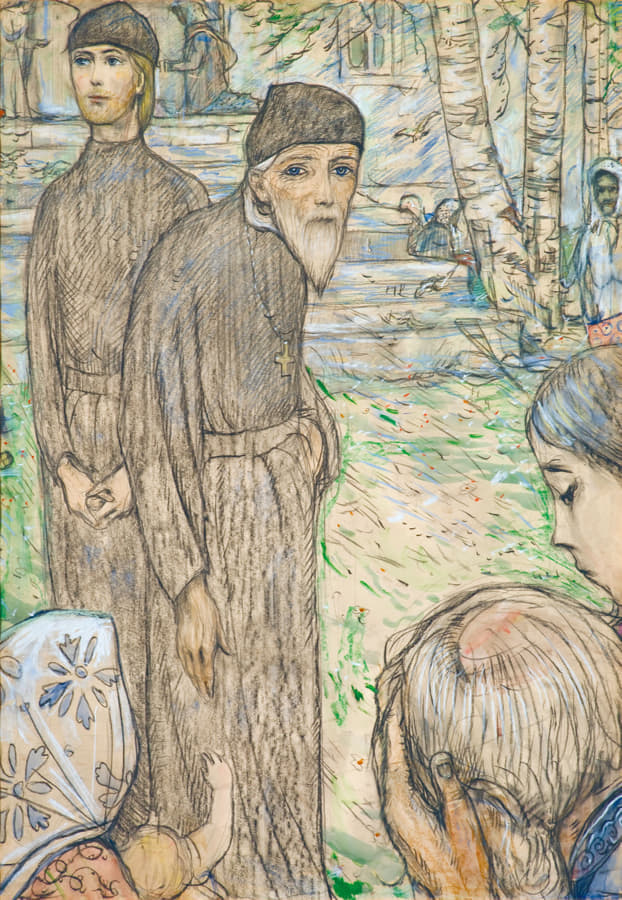

Man is in the Place of the Cosmos. Don’t Slip into the Abyss

The rest of the creation process already transforms chaos into cosmos. God’s spirit, hovering over the waters, builds order in place of disorder. This is how stars, plants, animals, people, and fish appear. But this cosmogonic act was not of much interest to the Jews (unlike the Greeks). Their religion dealt with an already created world (the cosmos) that needed to build a right relationship with God the Creator through man. Man stood in the place of chaos. He could slip into the abyss of Abaddon, or he could ascend to the heavens, like Elijah. In the Book of Job (28:22) Abaddon as Earth, Chthoniê in Pherecydes, is mentioned in the context of the veil. The veil is the cosmos. Man is the world, but it is based on chaos. This is true, but Jewish and later Christian theology almost never refers to chaos. Here everything is personified—and even the enemy of man, the devil, is not a molded element, but the quite distinct personality of a fallen angel. In the Christian era, chaos recedes to the periphery, following in many ways Judaism, especially the later one.

Gas: The Dutch Alchemists’ Chaos

We see a certain interest in chaos during the Renaissance, and especially among the alchemists. Thus, the word “gas” comes from the Dutch alchemist J.B. van Helmont, who understood it as a “gaseous state of matter,” and in Dutch it means “chaos.” In this more prosaic capacity, chaos-gas finds its way into modern chemistry and physics. But it has little in common with the grandiose cosmogonic and even ontological concept of ancient metaphysics.

Chaos: The Unrecognized Essence of Materialism

A new wave of fascination with chaos came in the twentieth century. With increasing attention to pre-Christian—primarily Greco-Roman—culture, many ancient theories and concepts were rediscovered. Among them was the complex notion of chaos, which offered a very different movement of cosmogonic thought from the creationist narrative of Christianity, on whose overthrow modern materialist science is based. We have seen how close the early interpretation of chaos was to matter. And it is even strange that materialists for so long were unwilling to see this, despite the fact that the parallels between the ideas about matter and those about chaos are surprisingly consonant and analogous. But even despite the fascination with chaos, no full-fledged conclusions have been drawn about this interpretation of materialism, and the study of chaos has unfolded on the periphery of philosophy.

Unpredictability

In physics, chaos theory began to emerge in the second half of the twentieth century among those scientists who were primarily concerned with nonequilibrium states, nonlinear processes, nonintegrable equations, and divergent series. During this period, physical and mathematical science highlighted a whole vast field that represented something that defied classical calculus models. Generally speaking, this could be called “unpredictability. One example of such unpredictability is a bifurcation—a state of some process (e.g., particle motion), which with absolutely equal degree of probability at some particular moment can flow both in one direction and in a completely different direction.

If classical science explained such situation by insufficiency of understanding of a process or knowledge about aggregate parameters of system functioning, then the concept of bifurcation suggested to consider such a situation as a scientific given and to move to new formalizations and calculation methods, which would initially allow such situations and in general would be based exactly on them. This was solved both through the appeal to Probabilistic Situation Calculus, modal logic, construction of the World-Sheet Action for the Three-Dimensional Ising Model (in superstring theory), including a vector of irreversible time inside a physical process (rather than as the absolute Newton-time or even understanding time in the four-dimensional Einstein system). All this can be called “chaos” in modern physics. In this case, “chaos” does not mean those systems that are generally impossible to calculate and in which there is no regularity. Chaos is amenable to calculations, influences and can be explained and modeled—like all other physical processes, but only with the help of more complex mathematical constructions, special operations and methods.

Subduing Chaos without Constructing Order

It is possible to define this whole field of research into chaotic processes (as understood by modern physicists) as an effort to master chaos. It is important that we are not talking about building a cosmos out of chaos. It is rather the opposite—the construction of chaos from the remains, the ruins of space. Chaos was suggested, not to eradicate it, but to comprehend and, in part, deepen it. To control and moderate it, not overcome it. And since not everywhere was the level of chaos advanced enough, chaos had to be artificially induced by pushing the decaying rationalistic order toward it. Thus, studies of chaos acquired a kind of moral dimension: the transition to chaotic systems and the art of managing them were perceived as a sign of progress—scientific, technical, and then social, cultural and political.

The New Democracy as Social Chaos

Chaos theories were now gradually shifting from fundamental physics and the philosophy of myth to the sociopolitical level. If classical democracy assumed the construction of a hierarchical system, only pushing back the decisions of the majority, the new democracy sought to delegate as much power as possible to individual persons. This inevitably leads to a chaotic society and changes the criteria of political progress. Instead of ordering it, progressives seek new forms of control—and these new forms move further and further away from classical hierarchies and taxonomies and gradually converge with the paradigms of the new physics with its priority given to the study of the realm of chaos.

Postmodernity: Chaos Strikes

In culture, the representatives of Postmodernism and Critical Realism took this up, and enthusiastically began to apply physical theories to society. At the same time there was a transition from the quantum model, which was not projected onto society, to synergetics and chaos theory. Society henceforth did not have to create any normative hierarchical systems at all, shifting to a network protocol—to the concept of rhizome (Deleuze and Guattari). The model became the case of the mentally ill seizing power over doctors in the clinic and building their own liberated systems. In this, the progressives saw the ideal of an “open society”—generally free of strict rules and laws, and changing their attitudes via purely random arbitrary impulses. Bifurcation became a typical situation, and the general unpredictability of schizoid people would be placed in complex nonlinear theories. Such people could be controlled, not directly, but indirectly—by moderating their seemingly spontaneous, but in fact strictly predetermined thoughts, desires, impulses and aspirations. Democracy was now synonymous with chaos. The masses were not just choosing order, they were overthrowing it, leading the way to total disorder.

Pacifism and the Internalization of Chaos

Thus, we come to the connection between chaos and war. Progressives traditionally reject war, insisting on the rather historically dubious thesis that “democracies do not fight each other.” If democracy inherently contains the idea of undermining normativity and order, the hierarchy and cosmic organization of society, then sooner or later history leads democracy to the point where democracy does turn into pure chaos (this is exactly what Plato and Aristotle believed, convincingly demonstrating that this is logically inevitable). The abolition of states, following the pacifist notion that war is an inherent part of the state, should lead to universal peace (la paix universelle), since de facto and de jure the legitimate means of war would disappear. But states perform the function of harmonizing chaos; and sometimes for this very purpose they throw destructive energies outward, toward the enemy. So, the war on the outside helps to keep the peace inside. But all this is in classical democracy—and especially in the theories of realists.

The new democracy rejects the practice of exteriorizing the dark side of man in the context of national mobilization. Instead, the most responsible philosophers (such as Ulrich Beck) propose the interiorization of the enemy, to put the Other inside oneself. This is in fact a call for social schizophrenia (quite in the spirit of Deleuze and Guattari), for a split in consciousness. If democracy becomes chaos, then the normative citizen of such a democracy becomes a chaotic individual. He is not going into a new cosmos; on the contrary, he drives out the remnants of cosmos, taxonomies, and order—including gender, family, rationality, species, etc.—out of himself definitively. He becomes a bearer of chaos. But—unlike Nietzsche’s formula—progressives taboo the act of giving birth to a “dancing star”—unless we are talking about a strip bar, Hollywood or Broadway. The schizo-citizen is not able to build a new cosmos under any pretext—after all, that’s why the old one was so hard-won.

Chaos democracy is post-order, post-cosmos. Destroying the old is proposed not to build something new, but to sink into the pleasure of decay, to succumb to the allure of ruins, rubble, fragments and decay. Here, on the lower levels of degeneration and degradation, new horizons of metamorphosis and transformation open up. Since there is no longer any hierarchy between baseness and heroism, pleasure and pain, intelligence and idiocy, what matters is the flow itself, being in it; the state of being connected to the network, to the rhizome. Here everything is side-by-side and infinitely far away at the same time.

Schizoids

In doing so, the war does not disappear, but is placed inside the individual. The chaotic individual wages war with himself; he aggravates the schism. Etymologically, schizophrenia means “dissection,” “cutting,” “dismemberment” of consciousness. The schizophrenic—though outwardly calm and peaceful—lives in a state of violent rupture. He lets the war in. This is how Thomas Hobbes’ hypothesis of the “natural state” of humanity, described by this author as chaos and war of all against all, is justified in a new way. However, this is not an early “natural” state, but a later one; not preceding the construction of hierarchical types of societies and states, but following their collapse. We have seen that chaos is the opposite of cosmos, just as enmity is the opposite of love in Empedocles. We have also seen that Eros and chaos are alternative states of the topos of the great in-between. So, chaos is war. But not all war, because the creation of order is also war, violence, taming the elements, ordering them. Chaos is a special war, a total war, penetrating deep inside. This is a schizoid war, capturing in its rhizomatic net the whole person.

Total War as a War of Chaos

Such total schizo-war has no strictly assigned territory. A knight’s tournament was possible only after marking out the space. Classical wars had theaters of operations and battlefields. Beyond these boundaries was space. Chaos was given strictly designated zones of peace. Modern war of chaotic democracy knows no boundaries. It is waged everywhere, through information networks, drones, UAVs, through the mental states of bloggers who let the underlying chasm shine through.

Modern warfare is a war of chaos by definition. It is now that the concept of discordia, “enmity,” which we find in Ovid and which is inherent in some—rather ancient—interpretations of chaos, opens up. Chaos is based precisely on enmity—and not on the enmity of some against others, but of all against all. And the purpose of the war of chaos is not peace or a new order, but the deepening of hostility to the very last layers of human personality. Such a war wants to remove the human connection to the cosmos, and at the same time to deprive the creative power to create a new cosmos, the birth of a new star.

Such is the democratic nature of war. It is conducted not so much by states as by hysterically divided individuals. Everything is distorted here—strategy, tactics, the ratio of technical to human, speed, gesture, action, order, discipline, etc. All this is already systematized in the theory of network-centric warfare. Since the early 1990s, the U.S. military leadership has sought to implement the theory of chaos in the art of war. In 30 years, this process has already passed through many stages.

The war in Ukraine has brought with it exactly this experience—the direct experience of confrontation with chaos.

Part 2. New World Chaos

The Conflict of Two World Orders

It seems that in the Special Military Operation, we are talking about a conflict of two world orders—unipolar, which is represented by the collective West and Ukraine, and multipolar, which is defended by Russia and those who are willy-nilly on its side (primarily China, Iran, North Korea, some Islamic states, partly India, Turkey, but also Latin American and African countries). This is exactly what it is. But let’s look at the problem from the point of view that interests us and find out what role chaos plays here.

Let us emphasize at once the point that the term “world order” clearly appeals to an explicit structure; that is, it is the antithesis of chaos. So, we are dealing with two models of the cosmos—unipolar and multipolar. If so, it is a clash between worlds, between orders, structures; and chaos has nothing to do with it.

The West offers its own version—the center and the periphery, where it is itself the center and the center’s system of values. Russia and (more often passively) its supporting countries advocate an alternative cosmos: there are as many civilizations as there are worlds. One hierarchy against several, organized according to autonomous principles. Most often on a historico-religious basis. This is how Huntington envisioned the future.

The clash of civilizations is a competition of worlds, orders. There is a Western-centric and there is a pluralistic one.

In this context, the Special Military Operration seems to be something perfectly logical and rational. The unipolar world, nearly established after the collapse of the bipolar model in 1991, does not want to give up its leading status. New centers of power are fighting to free themselves from the power of a decaying hegemon. Even Russia might be in a hurry to challenge it directly. But you never know how weak (or strong) it really is until you try. In any case, everything here is quite clear: there are two models of the cosmos battling each other—one with a pronounced center and other with several.

Either way, there is no chaos here. And if we encounter something similar to it, it is only as a phase-transition situation. This would partly explain the situation in Ukraine, where chaos makes itself felt in full force. But there are other dimensions to the problem.

Hobbes’ Chaos: The Natural State and the Leviathan

Let’s take a closer look at what constitutes a unipolar Western-centric world order. It is not just the military and political domination of the U.S. and vassal states (primarily NATO countries). It is also the implementation of an ideological project. This ideological project corresponds to a progressive democracy. The meaning of “progressive democracy” is that there should be more and more democracy, and that the vertical model of society should be replaced by a horizontal one—in the extreme case, a network, rhizomatic.

Thomas Hobbes, the founder of Western political science, imagined the history of society as follows: In the first phase, people live in a natural state. Here, “man is a wolf to man” (homo homini lupus est). It is an aggressive initial social chaos, based on selfishness, cruelty and force. Hence the principle of war of all against all. This, according to Hobbes, is the nature of man, for man is originally evil. Evil, but also clever.

The intelligence in man told him that if you continue to be in a natural state, people sooner or later will kill each other. And then it was decided to create a terrible man-made idol, the Leviathan, who would impose the rules and laws and make sure that everyone followed them. Thus, mankind solved the problem of coexistence of wolves. The Leviathan is a super-wolf, knowingly stronger and crueler than any of the humans. The Leviathan is the state.

The tradition of political realism—first of all in international relations—stops there. There is only the natural state and the Leviathan. If you don’t want the one, you get the other.

Chaos in International Relations in the Realist Tradition

This model is quite materialistic. The natural state corresponds to aggressive chaos, enmity (νεῖκος)—the one that represents Empedocles’ alternative to love/friendship. The introduction of the Leviathan balances enmity by imposing on all “wolves” rules and norms, which they dare not violate for fear of punishment and, in the end, death. Hence the formula put forward much later by Max Weber—”the state is the only subject of legitimate violence.” The Leviathan is knowingly stronger and more terrible than any predator, and therefore is able to stop a series of irreversible aggressions. But the Leviathan is not love, not Eros, not psyche. It is only a new expression of enmity, total enmity, raised a degree higher.

Hence the right of any sovereign state (and the Leviathan is sovereign and this is its main feature) to start a war with another state. While pacifying enmity inside, the Leviathan is free to unleash war outside.

It is this right to war that becomes the basis of chaos in international relations, according to the school of realism. International relations is chaos precisely because there can be no supreme authority between several Leviathans. At the macro level, they repeat the natural state: the state is selfish and evil because the person who founded it is selfish and evil. Chaos is frozen within, to reveal itself in war between states.

Political realism is not entirely extinct in democracies to this day, but neither is it considered a legitimate point of view in international relations.

Locke’s Order

But that is not all. Hobbes was followed by another important thinker, John Locke, who formulated a different school of political thought, liberalism. Locke believed that man himself was not bad, but rather ethically neutral. He is tabula rasa, a blank slate. If the Leviathan is evil, so will his citizens be evil. But if the Leviathan changes his temperament and his orientations, he is able to transform the nature of people. People themselves are nothing—you can make wolves out of them or you can make sheep out of them. It’s all about the ruling elite.

If Hobbes thinks of the state that existed before the state and predetermined its monstrous character (hence Hobbes’ chaos) and compares it with the state, Locke considers the already existing state and what might follow, if the state itself ceases to be an evil monster and becomes a source of morality and education, and then disappears altogether, handing the initiative to reeducated—enlightened—citizens. Hobbes thinks in terms of past/present. Locke thinks in terms of the present/future. In the present, the state is evil, selfish and cruel (hence wars and chaos in international relations). In the future, however, it is destined to become good, which means that its citizens will cease to be wolves and wars will cease because mutual understanding will prevail in international relations. In other words, Hobbes proposes a dialectic of chaos and its relative removal in the Leviathan (with a new invasion of inter-state relations); while Locke proposes fixing the violent nature of the state by remaking (re-educating, enlightening) its citizens and abolishing war between nations. But the enmity inherent in Hobbes, Locke proposes to replace not with love and order, but with commerce, trade, speculation. The merchant (not the prophet, priest or poet) replaces the warrior. Thus, trade is called doux-commerce, “gentle commerce.” It is gentle compared to the brutal seizure of booty by the warrior after the capture of the city. But how brutal it is, is evidenced in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice.

Importantly, Locke thinks of the post-state purely commercial order as something that follows the age of states. This means that the collective mind hypostasized in the Leviathan is by no means abolished, but only brought down to a lower level. A re-educated, enlightened citizen (former wolf) is now a Leviathan himself. But only a new one. By re-educating his subjects, the enlightened monarch (synonymous with an enlightened state) re-educates himself.

World Government as an Enlightenment Project

This is where the theory of political democracy begins. The state enlightens its citizens, uproots aggression and egoism, and becomes altruistic and pacifist itself. Hence, the main law of international relations: democracies do not fight each other.

And further, If states are no longer selfish (sovereign), they are capable of democratically establishing a supra-state instance of World Government, which will see to it that all societies are good and only trade among themselves, and never go to war. Gradually, states are abolished and One World, a global civil society, comes into being.

Economics: Locke’s Chaos

It would seem that in Locke, and in the later tradition of liberalism that continues his ideas, chaos has been removed. But not so. There is no military chaos, but there is an economic chaos. Thus, there is no aggression, but the chaos remains. And aggression and hostility remain, but acquire a different character; namely the one imposed on society by the commercial (capitalist) state. And specifically, the Western European state of the New Age.

That the market should be free and the economy deregulated is the main thesis of liberalism, that is, modern democracy. Thus, chaos is reintroduced, but only under another guise—with aggression trimmed back and egoism outright. The Leviathan is identified with reason (it was established on its basis), and reason is thought of as something universal. Hence Kant and his transcendental reasoning and calls for universal peace. This reasoning is not abolished (along with the overcoming of the Leviathan), but is transformed, softened, collectivized (the Leviathan is collective), and then atomized into a multitude of units, written on the blank slates of atomic individuals. Post-state man differs from pre-state man in that the mind is henceforth his individual domain. This is how Hegel understood civil society. In it, the common rationality of the old monarchy is transmitted to the multitude of citizens—the bourgeois, the townspeople.

Therefore, in liberal theory, since the Leviathan is rationality, the distribution of rationality to all individuals eliminates the need for it. Society will be peaceful in this way (as predicted by the Leviathan above), and will realize its wolfish tendencies a step removed—through commercial competition. The liberal racist social Darwinist theorist Spencer says the same thing in a harsh form.

Gentle commerce, doux commerce, is gentle chaos; chaos in the context of liberal democracy.

The New Democracy and Governance: The Gentle Chaos of Dissipation

In the West there is a balance of Hobbes and Locke, a pessimistic and retrospective understanding of the state (and of human nature itself) and an optimistic progressivist one. The former is called “realism,” the latter “liberalism.” Both modern, Western-centered, modernist theories coincide in general, but differ in particulars. Primarily in the interpretation of chaos. For realists, chaos is inherently evil and aggressive. And it was to combat it that the state was created—the Leviathan. But the chaos did not disappear; it went from the internal to the external. Hence the interpretation of the nature of war in realism.

Liberalism shares the interpretation of the genesis of the state, but believes that evil in man can be overcome, with the help of the state, which transforms (enlightens) and then enlightens its citizens as well—up to the point of penetrating their code, their nature. Here, the state, and above all the enlightened state, acts as a programmer, installing a new operating system in society.

With the success of liberalism, the theory of a new democracy or globalism began to take shape. Its essence is that nation-states are abolished, and with them disappear wars, and the very aggressive and selfish nature of man is changed by social engineering, which transforms man—turns the wolf into a sheep. The Leviathan no longer exists, and the old—military-aggressive, wolfish—chaos is abolished. The chaos of global trade, the mixing of cultures and peoples, the flows of uncontrolled migration, multiculturalism, the mixing of everyone and everything in the One World begins.

But this generates a new chaos. Not aggressive, but soft, “gentle. At the same time, control is not abolished, but descends to a lower level. Whereas government, even in the old democracy, was an elected, but hierarchical, vertical structure, now it is a question of governance, or “governing,” in which power enters the interior of the governed subject, fusing with it until it is indistinguishable. Not censorship, but self-censorship. Not control from above, but self-control. This is how the vertical Leviathan plasmatizes in the horizon of scattered atomic individuals, entering into each of them. It is a hybrid of chaos (the natural state) and the Leviathan (universal rationality). In fact, this is how Kant thought of civil society. The universal spills over into atoms, and now it is no longer an external instance, but the enlightened citizen’s own individual reasoning that curbs his own aggressiveness and moderates his own egoism. This is how violence is placed inside the individual. Chaos splits not power and the masses, not states among themselves, but man himself. This is Ulrich Beck’s Risk Society (Risikogesellschaft)—the danger now emanates from the self, and its own schizophrenic splitting becomes the norm.

Thus, we arrive at the schizo-individual, the bearer of the particular chaos of the new progressive liberal democracy. Instead of harming others, the liberal “chaoticist” harms himself, beats himself, splits and divides. Sex reassignment surgery and the promotion of sexual minorities in general are a godsend. The optionality of gender, the freedom to choose between two autonomous identities in one and the same individual. Gender politics allows “chaoticism” to take full effect.

But it is a special chaos, devoid of formalization in the form of aggression and war.

“Chaotic” as the Human Norm of the New Democracy

This is the order of the new democracy that the West seeks to impose on humanity. Globalism insists on commercial chaos (the free market) combined with LGBT+ ideology, which normalizes the split within the individual, postulates “chaoticism” as an anthropological model. This assumes that rationality and the prohibition against aggression are already included in “chaoticism”—through the mass demonization of nationalism and communism (primarily in the Soviet, Stalinist version).

It turns out that the unipolar world, and the corresponding global order, is an order of progressive chaos. It is not pure chaos, but not order in the full sense of the word. It is a “governance” that tends to be rolled out horizontally. This is why the thesis of World Government is too hierarchical, too Leviathanian. It is more correct to speak of a World Governance, a World Governance that is invisible, implicit. Gilles Deleuze was right to point out that during the epoch of classical capitalism, the image of the mole is optimal: capital works invisibly to undermine traditional, pre-modern structures and build its own hierarchy. The image of the snake suits the new democracy better. Its flexibility and its wriggles point to the hidden power that has entered the atomized mass of the world’s liberals. Each of them individually is the bearer of spontaneity and chaotic unpredictability (bifurcation). But at the same time, a rigid program is built into them, predetermining the whole structure of desire, behavior, and goal-setting—like a factory with working desire-machines. The freer the atom is in relation to the constellation, the more predictable its trajectory becomes. This is exactly what Putin meant when he quoted Dostoyevsky’s The Demons in his passage about Shigalev: “I begin with absolute freedom and end with absolute slavery.” The Leviathan as a global idol, a man-made omnipotent demon is no longer needed, since liberal individuals become small “Leviathans”—exemplary “chaoticists,” freed from religion, estates, nation, gender. And the hegemony of such a progressive-democratic West represents not just order in the old sense or even democratic order, but precisely the hegemony of “peaceful” chaos.

Pacifists Go to the Front

To what extent is this Lockeian chaos peaceful? To the point where it faces no alternative; that is, no order. Moreover, we can talk about the order of the West itself, even about the old Hobbesian democracy (it can be collectively called Trumpism or old liberalism); and even more about other types of order, generally undemocratic, which the West collectively calls “authoritarianism,” meaning the regimes of Russia, China, many Arab countries, etc. Everywhere we see other articulations of order that openly and explicitly oppose chaos.

And here is an interesting point: when confronted with the opposition, the pacifist liberal New Democratic West goes mad and becomes extremely militant. Yes, democracies do not fight each other, but with non-democratic regimes, on the contrary, the war must be merciless. Only a “chaotic,” with no gender or other collective identity, is a person; at least a person in the progressive sense. All the rest are the backward, unenlightened masses on which the vertical order, either the cynical Leviathan or even more autonomous and autarkic versions of the order, rests. And they must be destroyed.

Post-Order

Thus, the unipolar world enters a decisive battle with a multipolar world, precisely because unipolarity is the culmination of a will to end order in general, replacing it with a post-order—a New World Chaos. The interiorization of aggression and schizo-civilization of “chaoticists” is possible only when there are no borders in the world—nations, states, “Leviathans;” that is, order as such. And until there is, pacifism remains utterly militant. Transgenders and perverts get their uniforms and set out for an eschatological battle against the opponents of chaos.

Chaos Gerasene Pigs

All this throws a new conceptual light on the Special Military Operation; Russia’s civilizational war with the West, against unipolarity and for multipolarity. The aggression here is multi-dimensional and has different levels. On the one hand, Russia proves its sovereignty, and thus accepts the rule of chaos in international relations. No matter how you look at it, this is a real war, even if not recognized by Moscow. Moscow hesitates for a reason—this is not a classic military conflict between two nation-states. This is something else—it is the battle of a multipolar order against unipolar chaos, and the territory of Ukraine is here precisely a conceptual frontier. Ukraine is not order, not chaos, not a state, not a territory, not a nation, not a people. It is a conceptual fog, a philosophical broth in which the fundamental processes of phase transition are going on. Out of this fog can be born anything. But so far it is a superposition of different kinds of chaos, which makes this conflict unique.

If we view Russia and Putin as realists, the Special Military Operation is a continuation of the battle to consolidate sovereignty. But this implies a realist thesis of the chaos of international relations and hence the legitimization of war. No one can forbid a truly sovereign state to do or not to do something, as this would contradict the very notion of sovereignty.

But Russia is clearly fighting not only for a national order against the globalist-controlled chaos, but also for multipolarity; that is, the right of different civilizations to build their own orders; that is, to overcome the chaos with their own methods. Thus, Russia is at war with the New World Chaos just for the principle of order—not only for its own, Russian order, but order as such. In other words, Russia seeks to defend the very world order that is opposed to Western hegemony, which is the hegemony of interiorized chaos; that is, globalism.

And another important point. Ukraine itself is a purely chaotic formation. And not only now. In its history, Ukraine is a territory of anarchy; a zone where the “natural state” prevailed. A Ukrainian is a wolf to a Ukrainian. And he is even more a wolf to a Muscovite or a Yabloko. Ukraine is a natural area of anarchic free-will, an entire playground, where atomized chubby autonomists seek profit or adventure, unconstrained by any framework. Ukraine, too, is chaos, hideous, inhumane, and senseless. It is ungovernable and cumbersome. Chaos of rampaging pigs and their friends.

These are the Gerasene pigs, into which the demons cast out by Christ entered and they rushed into the abyss. The fate of Ukraine—as an idea and a project—comes down to that very symbol.

Special Military Operation—The War of Polysemantic Chaos

It is not surprising that different types of chaos collided with each other in Ukraine. On the one hand, the global controlled chaos of Western new democracy has supported and oriented the Ukrainian “chaoticists” in their confrontation with the Russian order. Yes, this order is still only a promise, only a hope. But Russia, from time to time, behaves exactly as this hope’s bearer. We are talking about empire, multipolarity, and confrontation with the West head-on. Most often, however, this vector is clothed in the form of sovereignty (realism), which made the Special Military Operation possible. We should not lose sight of the deep penetration of the West inside Russian society—the chaos in Russia itself has its own serious backing, which undermines the vector of Russia’s identity and the defense of its order. The fifth and sixth columns in Russia are supporters of Western chaos. They are the ones who are sharpening and corroding the will of the state and the people to win in the Special Military Operation.

Therefore, Russia in the Special Military Operation, being a priority on the side of order, acts at times according to the rules of chaos, imposed by the West (New World Chaos), as well as by the nature of the enemy itself.

Russian Chaos

Russian Chaos. It must win, by creating a Russian Order.

And the last thing. Russian society has a chaotic beginning in itself. But it is another chaos—the Russian chaos. And this chaos has its own characteristics—its own structures. It is opposite of the New World Chaos of liberals, because it is not individualistic and material. It is also different from the heavy, meaty, bodily-sadistic chaos of Ukrainians, which naturally breeds violence, terrorism, trampling all norms of humanity. Russian chaos is special; it has its own code. And this code does not coincide with the state; it is structured completely independent of it. This Russian chaos is closest to the original Greek, which is a void between Heaven and Earth, which is not yet filled. It is not so much a mixture of the seeds of things warring against each other (as in Ovid) as it is a foretaste of something great—the birth of Love, the appearance of the Soul. Russians are a people preconditioned for something that has not yet made itself fully known. And it is precisely this kind of special chaos, pregnant with new thought and new deed, that Russian people carry within them.

For such a Russian chaos, the frameworks of the modern Russian statehood are cramped and even ridiculous. This chaos carries the seeds of some inconceivable, great, impossible reality. Russian dancing star.

And the fact that the Special Military Operation includes not just the state, but the Russian people themselves, makes everything even more complex and complicated. The West is chaos. Ukraine is chaos. The Russian people are chaos. The West has order in the past. We have order in the future. And these elements of order—fragments of the order of the past, elements of the future, outlines of alternatives, conflicting edges of projects—are mixed in with the battle of chaos.

No wonder the Special Military Operation looks so chaotic. This is the war of chaos, with chaos, for chaos and against chaos.

Russian Chaos. It is this that must win, creating a Russian Order.

Part 3. Chaos and the Principle of Egalitarianism

Orbital Systems of Society

The most important feature of chaos is mixing. When applied to society, it results in the abolition of hierarchy. In Интернальные онтологии (Internal Ontologies) we discussed how unsolvable social problems and conflicts arise when the orbital structure of society is replaced by a horizontal projection. Orbitality is taken as a metaphor for the movement of planets along their trajectories, which in the case of the volumetric model does not generate any contradictions, even when the planets are on the same radius, drawn from the center of rotation. It is orbitality that allows them to continue moving freely. If we project the volume on the plane and forget about this procedure, the planets will collide with each other. And, accordingly, the effects of such a collision will be produced.

When applied to society, this gives a situation thoroughly explored by the sociologist Louis Dumont in his programmatic work Homo Hierarchicus and in his Essays on Individualism. In Indian society, where the principle of orbitality as represented by the caste system is preserved, the conflict and contradiction between the ideal of individual freedom and the strict regulation of social life for different strata and types of society is not even remotely visible. Neither was it found in the institution of Christian monasticism, along with the preservation of the medieval system of estates. Simply freedom and a rigid system of social obligations and boundaries were placed on different levels, without creating any contradictions or collisions. Staying in society, that is, moving along the social orbit, one was obliged to strictly follow caste principles down to the smallest detail. But if one chose freedom, a special territory was set aside for this—personal ascesis (monasticism in Christianity, hermitage of sanyasis in Hinduism, sangha in Buddhism, etc.), which was considered quite a legitimate and socially accepted norm. But personal spiritual realization was situated in a different orbit, in no way detracting from class organization.

Dumont shows that the problems begin precisely when democratic egalitarianism begins to prevail in Western European society and bourgeois notions displace the medieval hierarchical order. The question of freedom and hierarchy is now projected onto the plane, making the problem fundamentally unsolvable. Individualistic society seeks to ascribe freedom no longer to a select few ascetics, but to all its members—by abolishing estates. But this expansion of individual freedom, not outside society (in the forest, in the wilderness, in the monastery), but within it, generates even greater restrictions. All individuals, placed on the same plane and deprived of their orbital—caste—radii, encounter each other randomly, further restricting the freedom of the other—and in a chaotic and disorderly manner.

Such dogmatic individualism still produces a hierarchy, but only this time based on the basest criterion—either money (as in liberalism) or a place in the party hierarchy as in totalitarian socialist societies. And the fact that such a de facto hierarchy develops in an egalitarian culture makes it even more acute, because it represents a logical contradiction and outrageous injustice.

Bourgeois Order is Bourgeois Chaos

Here again we are dealing with a pair—order/chaos. Egalitarianism destroys qualitative hierarchical order, social orbitality. Thus, it produces just chaos: random encounters between individuals. At the same time, the interaction between them is reduced to the lowest, bodily, levels, since it is these that people of different cultures, types, and spiritual orientations share. Carriers of finer organization, who occupy the place of the elite in hierarchical societies, are thrown down to the corporeal bottom, where they are forced to find themselves among beings of much coarser nature. This is the mixing or projection of orbital types on the plane.

And the higher types, of course, are drawn to such a position and create socio-psychological vortexes around them. Having no legitimate place, they begin to stir up chaotic processes. Added to this is the disordered search for total freedom, which everyone is invited to engage in, not in a special—ascetic—zone, but in the thick of society. This exacerbates the chaos in egalitarian societies.

Classical democracy believes that a solution to this problem should be sought in the construction of a new—this time democratic—hierarchy. But such a secondary hierarchy is no longer orbital, volumetric and qualitative, but is constructed on the basis of the material-bodily attribute. It is a horizontal “hierarchy” that does not overcome chaos; but on the contrary, makes it increasingly fierce. The main criterion in such a bourgeois-egalitarian society (which declares equality of opportunities) is money; that is, the generalized equivalent of material wealth. Any other hierarchy is rigidly rejected. But the stratification of society into the ruling rich and the subordinate poor, up to the point of reducing the proletarians practically to slave-like living conditions, does not remove the contradictions. And in this, socialist theories and Marxism are quite right—in capitalism, class antagonism only grows as the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

Egalitarian chaos is not relieved by the transition from classical hierarchy to the hierarchy of money; but, on the contrary, it erupts into violent class wars. Where there is chaos, there is war, as we have repeatedly noted. Therefore, as capitalism develops according to its autonomous logic, it cannot but produce a series of systemic crises, moving toward a final collapse. Chaos takes over.

The Socialist Chaos of Totalitarian Bureaucracy

An alternative, but also egalitarian model of socialism proposes to solve the problem by abolishing even the material, monetary hierarchy, insisting on full property equality. Here all hierarchy is denied, and class antagonism is proposed to be removed, through the abolition of the entire capitalist class. Communism is thought of as a peaceful utopian chaos in which there will be no contradictions and full equality will triumph.

This, however, contradicts the nature of chaos, which manifests itself precisely in disordered collision. And the flatter—as in communist theories—the social model is, the more explosive the manifestation of chaos.

We see this in the level of violence in communist societies, which manifested itself in systemic repression, and in the creation of party bureaucratic hierarchies, driven primarily by the need to punish—first, class enemies, and then, just the unconscious part of society.

Both capitalism and communism, in their classical versions, in their variously egalitarian systemic versions, attempt to abolish hierarchy (orbitality), but at the same time to tame chaos, to make it predictable, controllable and “soft.” However, this contradicts the nature of chaos, which is oriented against any order—even horizontal order.

The Radical Egalitarianism of the Postmodern: Feminism, Ecology, Transhumanism, LTBG+

The new democracy already discussed proceeds from the fact that previous egalitarian projects, both bourgeois and socialist, failed in their mission; and instead of completely abolishing the hierarchy, they re-framed it in new forms. Capitalist societies created a new ruling class out of the rich, while socialist regimes created new hierarchies of the party nomenklatura. In this way, the goal was not achieved. This is where the Postmodern begins.

In the Postmodern, or new democracy, the problem of equality is posed with a new acuteness, taking into account the preceding stages and social experiments. Thus, the theory of the necessity of a radicalization of equality; that is, the transition to an even more horizontal social model, from which all verticality—even two-dimensional and materialistic—is removed. This leads to four major trends of new democracy:

• equality of the sexes,

• equality of species,

• equality of people and machines,

• equality of objects.

Gender equality is realized through feminism, the legalization of gay marriage, transgenderism, and the promotion of the LGBT+ agenda. Gender ceases to be an orbital distinction, where men move in their orbit, women in theirs, but both mix randomly in a chaotic mass of gender uncertainty and a fickle chain of temporary playful identities.

Deep ecology seeks to equate humans with other animal species and, more broadly, with other environmental phenomena, reducing humanity to a purely natural phenomenon; or, at times, even a harmful anomaly.

Transhumanism seeks to equate man with a machine, and to insist on his equality with a technical apparatus, albeit a fairly advanced one. But advances in technology and genetic engineering, as well as advances in the digital domain, allow for more advanced thinking systems, making man a kind of historical atavism.

Finally, object-oriented ontology denies the subject as such, regarding man as a random uncorrelated unit in a purely chaotic and irrational multitude of all kinds of objects.

Gender Chaos

Gender policy is designed to abolish hierarchy in the field of gender. This can be achieved in three ways, which determine the main trends in this area:

• To fully equalize men and women in all respects (radical feminism);

• Make gender a matter of individual choice (transgenderism);

• Abolish gender altogether in favor of a new type of genderless creature (cyberfeminism).

In the first case, society establishes the most brutal gender egalitarianism. In this case, female and male individuals cease to be socially distinct, which inevitably leads to gender chaos. In such a situation, some may continue to insist on their gender and its specificities (for example, women seeking to increase their rights as women), some are simply indifferent to gender identity, while others demand its complete abolition. This generates high turbulence and continuous clashes of chaotic individuals among themselves, under conditions of gender uncertainty. Obviously, the conflicts of confused atoms in such a situation do not diminish, but grow like a snowball.

The policy of turning gender identity into a matter of personal choice—with the expansion of the practice of anatomical sex-change operations into ever newer categories, up to and including children—leads to the fact that gender identity becomes a kind of easily replaceable paraphernalia, analogous to a fashionable costume. Gender changes as easily as clothes in a new season; which means that a person begins to be understood as an essentially sexless being, and this sexlessness constitutes his nature, reducible to pure individuality.

In this case, it is transgender people who emerge as the social norm. The tensions inherent in gender as such and the psychology associated with it are here distributed between individuals who encounter each other without any ordering algorithms. People’s attraction and repulsion cease to be subject to any norms, and the whole society becomes a pansexual field of vibrations of essentially sexless units. Something similar as an ideal is described by Deleuze and Guattari.

Finally, philosophically responsible feminists such as Donna Haraway, united under the term “cyberfeminism,” propose to abolish gender altogether, since all forms of it—including homosexuality, transgenderism, etc.—are based on a dual, asymmetrical and hierarchically organized code. Postmodern thought concludes that any distinction is already in itself an inequality, which means that someone will always be superior and someone inferior. In order to abolish this, it is necessary to absolutize and normalize a crystalline, sexless being. But humans and animals cannot become such. Consequently, cyberfeminists conclude, it is necessary to abolish man and put in his place a cyborg, a humanoid machine. Here, radical feminism is directly connected to transhumanism.

All of these trends are not alternative, but are developing in parallel. And it is easy to see that all of this adds up to the chaotic systems of the new democracy.

Eco-Chaos

Modern ecology applies egalitarianism to a different field. This time it is not gender identity (male/female inequality) but species identity (human/environment) that is at stake. Ecology demands that this inequality be mitigated, if not abolished. The most extreme versions of fundamental ecology put forward the idea that humans represent a fault line in the evolution of nature and should be abolished as an anomaly.

Human activity is polluting the environment, destroying ecological landscapes and many animal species. Humans litter the world’s oceans, cut down forests, disturb the earth’s interior, and contribute to mutations in the atmosphere, particularly in the ozone layer. Environmentalists suggest that we reconsider the thesis that man is the apex of creation and the peak of evolution and take it as axiomatic that man is one of the phenomena of nature and, therefore, has a number of primordial obligations to nature.

Previously, man and nature were thought of as two different realms—two orbits. The sphere of the mind and the sphere of the earthly material environment did not overlap. The philosopher Dilthey proposed to strictly divide the sciences into the sciences of spirit (Geistwissenschaften) and the sciences of nature (Naturwissenschaften)—each domain needs its own algorithms, principles, semantic structures.

Ecologists demand that this hierarchical distance be abolished and, at a minimum, spirit and matter, thinking and non-meaningful life, be equalized in rights. In addition, they insist on a radical revision of the relationship with the environment: it is not a zone of externality, but an existential landscape of human existence. Man is inscribed in nature and nature in man. And this reciprocal relationship must be equal and reversible.

Thus, ecological thought seeks to abolish yet another asymmetry—to reduce man to an animal species, to an element of nature. Man ceases to be the center and turns into the periphery—along with all other natural phenomena. Thus, man himself becomes a medium, a natural habitus.

Extreme versions of ecology go even further, and consider man an anti-nature phenomenon, a threat to the environment. Therefore, for the planet to live, the human species must be exterminated or at least significantly reduced. Otherwise, overpopulation, planetary catastrophe and the disappearance of life itself cannot be avoided.

This ecological approach—in a moderate version—seems quite reasonable and attractive. However, the rejection of hierarchy in this case, too, turns the natural-human ensemble into chaos. Nature itself does not have a pronounced center—everything in it is on the periphery, and therefore the approximation to its implicit logic (for example, in the postmodernist philosophy of Deleuze, where the priority of the tuberous rhizomatic principle is concerned) leads to further chaotization of man and human society.

Moving from the pastoral idyll to more responsible forms of ecological thought, we begin to notice that nature is inherently aggressive, violent, and powerfully amoral in the unfettered elements. Nature can smile, but it can also be angry; all of which is done independently of human behavior and in no way correlates these states with man or his mind (ecology categorically rejects any hint of anthropocentrism). That is why some ecological theories—above all those related to deep ecology—explicitly proclaim the laws of dark and blind aggression that prevail in nature as a model for the organization and human life. In Postmodern philosophy, this turn from the humanistic pastoral to sadistic and destructive pictures is generically called “Dark Deleuze,” since in some passages of this brilliant philosopher one can find Nietzschean motifs taken to an extreme, to celebrate life as a stream of blind, all-destroying aggression.

Chaos of Intelligent Machines

The degree of chaos is also heightened as the philosophy of transhumanism takes shape, beginning with an equation between man and machine. Here another hierarchical orbitality is overcome.

The notions of the closeness of man and machine had developed among New Age thinkers long before modern transhumanism. Materialism and atheism pushed exactly this interpretation of man as a perfect machine.

The French philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie explicitly stated this when he titled his seminal work, L’Homme machine [Man-Machine]. This thesis generalized such a trend in medicine as “iatromechanics” or “iatrophysics” (Giovanni Borelli, William Harvey, etc.), where various organs of the human body were presented as analogues of working tools: arms and legs as levers and joints, lungs as bellows, heart as a pump, etc. Descartes had even earlier insisted that animals were mechanisms which could easily be quantified in the future and their direct—and even more perfect—analogues could be created. But Descartes took the human mind—its subjectivity—out of this picture. La Mettrie went further than both Descartes and the “iatromechanics” and proposed that man entirely be regarded—not just his body—as a machine. Yes, this machine had as yet an unrecognized engine, the intellect that drove the whole mechanism, but in time it too would be computed, and hence a replica of it would be created.

As psychiatrists later studied the functioning of the brain, the idea of the mechanical structure of the mind was further developed, and the discovery of synapses in the cerebral cortex was seen as confirmation that science had come close to unraveling the functioning of consciousness.

From the figure of Man the Machine, materialist science developed the machine component, both in the body, the psyche, and neurology. In psychiatry, the “Helmholtz machine” theory, which developed La Mettrie’s thesis with a much greater degree of detail of the mechanical structure in man, was in circulation.

By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, neurobiology, cognitive science, digital technology and genetic engineering had come close to creating the model of the machine of which La Mettrie spoke. But still some uncertainty about Artificial Intelligence as a mock-up of consciousness persisted. Thus, in the field of Artificial Intelligence two areas were distinguished:

• the area of data accumulation, storage and systematization,

• neural networks capable of creating semantic structures (e.g., artificial languages) independently, without the operator’s participation.

The first area is sometimes called “Weak Artificial Intelligence.” It is far superior to the human brain in its speed and ability to store and manipulate data, but it lacks the will, which, together with reasonableness, is a necessary component of the subject. And so, the “Weak AI” is technically many times stronger than the human brain. And yet it is only a Machine, although superior to Man-Machine.

But a truly strong AI comes about when “weak AI”, i.e., the structure of data manipulation and technically controlled processes, is controlled not by a human operator, but by a powerful neural network. This is Strong Artificial Intelligence. This is where the will factor comes in. The machine is now fully Human. Now it is a Machine-Man.

Full transition from the Man-Machine hypothesis to the Machine-Man construction is the Singularity that modern transhumanists talk about. Once this moment arrives, the difference between man and machine, between organism and mechanism, will be abolished. Just as once apes (according to Darwin’s theory) gave birth to man, who picked up a tool and thus opened a new page of history, in the Singularity man will pass on the baton to Artificial Intelligence.

But such a transition represents the ultimate risk. Man and machine find themselves on the same plane for a while, colliding with each other. A human will not immediately weaken to the point of trusting the machine completely, which may well decide that further existence of the species is inexpedient. For example, if the neural network becomes acquainted with the teachings of the deep ecologists. And the Strong Artificial Intelligence itself will not immediately gain full energy autonomy and independence from hardware, and even from operators. The chaos that is sure to ensue in such a situation has been described many times in science fiction literature and vividly anticipated in cinema—in The Matrix, Mad Max, etc.

Once again, the egalitarianism of the new democracy inevitably leads to chaos, aggression, war, and brutality.

The Chaos of Objects

The most honest among postmodernists and futurists are the representatives of critical realism (or object-oriented ontology). They take New Age materialism to its logical end and demand the complete abolition of the subject. Quentin Meillassoux notes that all philosophy and science, even the most egalitarian and progressive, cannot go beyond correlation. Every object is bound to have a correlate, a pair, either in the realm of the mind (classical positivism), or among other objects. Meillassoux and other critical realists (Graham Harman, Ray Brassier, Timothy Morton, Nick Land, etc.) suggest abandoning the search for correlations altogether and immersing oneself in the object itself. This requires breaking definitively with the central position of reason and treating consciousness as an object among others.

In practice, this is possible only through the complete elimination of man as a subject, a bearer of reason. That is, man is now thought of as a mysterious, unknowable, arbitrary, and uncorrelated object like all things in the outside world. Meillassoux even criticizes Deleuze for overemphasizing life. Life is already a violation of the deep silence of the thing, an attempt to say something, and thus to introduce inequality, to create the preconditions of hierarchy and orbitality. Hence the proposal of object-oriented ontologists not just to abolish man, but to abandon the centrality of life.

Now even the chaos of biological species devoid of a human center is not enough. The next—and logically the last–stage of egalitarianism requires the rejection of life, including natural life. This theme is most vividly developed by Nick Land, who reduces the genesis of life and consciousness to a geological trauma to be overcome through the eruption of the Earth’s lava and the bursting of the Earth’s core through the shell of the cooled crust. According to Land, the history of life on earth, including human history, is only a small fragment in the geological history of the cooling of the planet and its quest to return to a plasma state.

In this model there is a transition from the apology of biological chaos to the triumph of material chaos. The abolition of all kinds of hierarchies and correlations reaches its apogee, and egalitarianism, brought to its logical limit, results in the direct triumph of dead chaos, destroying not only the subject but also life.

Egalitarianism is the Road to Chaos

The gendered, ecological and transhumanist agendas are already indispensable features of the new democracy today. The movement toward the final abolition of the subject and of life in general is a distinctive vector of the future. Egalitarianism is a movement toward chaos in all its forms. And always—contrary to the initial and purely polemical idyll—chaos appears as a synonym of enmity (νεῖκος) of Empedocles; that is the equivalent of war, aggression, destruction and annihilation.

Already the abolition of class hierarchies, placing people of a spiritual and military nature on the same plane as peasants, artisans, and laborers, generates an unnatural social environment in which there is a disorderly jumble of bodily impulses—as people of different natures have in common—and even then only in appearance—the body. Bourgeois society includes heterogeneous elements that cannot help but blur its systemic functioning. Moreover, the absence of higher orbits prevents the lower orbits from maintaining their trajectories. A slave without a Master (in Hegel’s formula), ceases to be a Slave, but does not become a Master, either. He falls into panic, begins to rush about; then to imitate the Master; then to return to the habitual consciousness of the Slave. This is already a state of chaos.

As egalitarian tendencies intensify, chaos only grows. And new democracy—in its postmodernist expression—is more and more openly admitting that it is leading the cause towards chaos and an increase in its degree. Not the other way around. While classical liberals relied on the invisible hand of the market to order the chaotic activity of desperately competing market agents, the new liberals openly seek to make the system more and more turbulent. This becomes the ideology and strategy of globalism.

Part 4. Chaos Theory in Military Strategy

The Article by Stephen P. Mann

Another dimension of chaos that should be examined in the context of the Special Military Operation is the application of chaos theory to the art of war. This is not a random reconstruction or a mere observation of the course of military operations on the Ukrainian front. It is more than that.

Back in 1992, the fall 1992 issue of Parameters, published by the U.S. War College, published a feature article by staff officer Steven R. Mann, deputy chief of the U.S. military mission in Sri Lanka, with the evocative title “Chaos Theory and Strategic Art.” The article offers a version of the application of the nonlinear logic explored in scientific theories of chaos to military strategy. Later, it was this approach that became dominant in the theory of network-centric warfare. In a sense, network-centric warfare is a practical implementation of the basic principles of chaos theory to the military sphere. Network-centric warfare is a war of chaos. Here, of course, chaos is understood in the spirit of modern physics—as the study of nonequilibrium, nonlinear systems, bifurcations, probabilism and weak processes. To the ancient chaos of philosophy, or to the chaos of political theory and international relations, this field has a rather indirect relation. Nevertheless, we are dealing precisely with chaos, which means that, after making all the necessary distinctions, we go back to the philosophical foundations. But this should be done cautiously and with careful consideration of all epistemological perspectives.

The Main Points of Chaos Theory

Steven R. Mann lists the main points of the physical theory of chaos thus:

• Chaos theory refers to dynamic systems—with a large number of variables.

• In these systems there are non-periodic regularities, seemingly random data nodes can add up to non-competitive, but nevertheless ordered patterns.

• Chaotic systems exhibit a sensitive dependence on initial conditions; any even slight change in the initial state leads to disproportionately divergent consequences.

• The presence of a certain order, suggests that patterns can be predicted—at least in systems with a weak level of chaoticity.

Mann emphasizes that there is no contradiction between chaos theories and classical physical and mathematical science. Chaos only nuances into physical laws and rules in some special classes—borderline or nonlinear—systems. Mann writes:

• Classical systems describe linear behavior and individual objects; chaos theory describes statistical trends with many intensely interacting objects.

• What is calculated here is not a set of linear trajectories, but the probabilistic behavior of systems—not predictable at the level of linear predictions, but embedded in a probabilistic trend.

Increasing the Concept of Theater to Nacro Proportions: Total War