To understand what “caesaropapism” means, we must compare and contrast this vague term with another, much clearer one, namely, “theocracy.” A theocratic society can be described as one ruled by, and over which “reigns,” God (1 Samuel 8:7), manifesting, directly or indirectly, His will in everything. The word itself, applied to the Jewish people, was created by Josephus Flavius. It fits both the original covenant theocracy embodied in the titanic figure of Moses, the divinely anointed kings of Israel, and the theocracy of the High Priests. The rigidity of the system was only marginally mitigated by the creation of the Levitical priesthood and the emergence of state authority: orders were always given by God, and in His name the prophets and interpreters of the Law spoke. Thomas Hobbes, followed by Spinoza, perfectly described this model: the agreement with God which this model presupposes, and the transfer of legal rights which it imposes. But while the latter declares the age of the prophets over, and warns against the slightest interference by the clergy in affairs of state, the former deduces from the example of Israel a “Christian republic,” in which the ruler “will take the same place as Abraham in his family” and will himself determine “what is the word of God and what is not.” This ruler would become by divine right the “supreme shepherd,” tending his flock and presiding over the Church in his state.

Going beyond Jewish history, these constructions and analyses have led sociologists to distinguish between several types of political organizations based on revelation and closely tied to religion: in some cases, the priests are content to lend legitimacy to secular authority (“hierocracy”); in others, the high priest or head of the community of believers ex officio also possesses supreme authority (theocracy proper); in still others, secular authority subordinates the religious sphere to a greater or lesser degree (forms of caesaropapism). This is how theocracy and caesaropapism, the model of the priest-king and the model of the king-priest, are opposed to each other.

Thus, the word “caesaropapism” stigmatized any “secular” sovereign who claimed to be a pope. The term itself has a sociological character, but it was used with an obvious polemical purpose, within the framework of a general classification that contrasted the theocratic or caesaropapist East with the West, where the independence of the “two powers” was perceived as dogma: in the first case there is confusion; in the second—distinction. Justus Henning Böhmer (1674-1749), professor at the University of Halle, in his textbook on Protestant ecclesiastical law (Jus ecclesiasticum protestantium), devoted an entire passage to the two main types of excesses of power in the religious sphere: “Papo-caesaria” and “Caesaro-papia.” In this way he sought, on behalf of the Reformed Church, to equate and denounce both the pope, who appropriated political power, and secular rulers dealing with religious problems, as Justinian had already done. Of the two opposed terms, only the second term was successful: it was often used in the second half of the nineteenth century, though not so much as a theoretical concept but to stigmatize Byzantium and its Orthodox successors: the “schisma” between the Christian East and the Christian West was said to have been caused by “Constantinian” or “Justinian” interference in matters of faith.

Such an approach turned the distinction between secular and spiritual authority into a complete incompatibility between the two. The vague notion of “caesaropapism” was reduced above all to a murderous-sounding word, which, however, could not be mollified by introducing a more genial definition; it was therefore impossible to raise the meaning of the word beyond the various currents of thought that gave it the derogatory character that has survived to this day. Thus, a brief review of historiography must precede any analysis of the essence of the problem.

To understand the essence of our problem and the ways in which it developed, it is necessary to mention briefly the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, that struggle of ideas which gave rise to Christian historiography as a reaction to critical reflections on the original truth of Christendom before its immersion in history.

Protestants instinctively disassociated themselves from all historical legitimacy, from that evolution which separated the clergy from all “other Christians, from that tradition which had established the Church in power. In his treatises On the Freedom of a Christian (1520) and On Secular Authority (1523) Luther paradoxizes the difference between the spiritual and the secular, starting from the Augustinian theory of the “two cities”: being part of both the spiritual and the secular cities, the Christian, according to Luther, is at the same time both absolutely free and absolutely enslaved. God created these two cities because only a small minority of true Christians belong to His city, while the vast majority need the “worldly sword” and have to submit to it, according to the covenant of Paul (Rom. 13:1: ” for there is no authority except from God”) and Peter (1 Peter 2:13: “accept the authority of every human institution”). But although worldly princes have their authority from God and although they themselves are Christians, they have no right to claim to “rule as a Christian” and in accordance with the Gospel. “The Christian kingdom cannot extend to the whole world, not even to one single country.” Between religion, understood primarily personally, and State, understood primarily in a repressive way, there can be no mutual accommodation; Luther sneers at those secular rulers who “arrogate to themselves the right to sit on God’s throne, dispose of conscience and faith, and… bring the Holy Spirit to the school pews,” just as he scoffs at popes and bishops “who become secular princes” and claim to be endowed with “authority” and not merely “office.” However, this radical separation of secular and spiritual does not lead to the recognition of the two powers, “since all Christians truly belong to the body of the Church,” and there is no reason to deny secular rulers “the title of priest and bishop.” It was not been easy to abide by these principles, and sometimes turned Lutheranism into a kind of caesaropapism (and Calvinism a kind of theocracy). But this new approach to “religion” undoubtedly carried with it the leaven which began the fermentation process by which the question of the origins of the Christian empire was fundamentally reconsidered in the 19th century.

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) made no determination on this question, but in proclaiming the Church to be the mediator between Christians and God, and giving sacred tradition the same weight as sacred Scripture, this Council brought together what Luther tried to divide. Both at the Council and around it, attempts were made to bring the two powers together rather than to separate them. The policy of the concordat was intended to find a difficult compromise between religious universalism and national churches. The Jesuits, on the other hand, supported the thesis of the “indirect power” of the pope in political affairs. And the justification they found, of course, in history. In thirteen volumes. of the Croatian Lutheran Matthias Vlacic (or Flacius Illyricus) and the Magdeburg “Centuriators” (1559-1575), who boldly called Pope Gregory VII a monster and thereby sowed confusion in the Catholic milieu; Caesar Baronius gave a belated response in twelve volumes of his Annales ecclesiastici (1588-1607). In this history of Christianity loomed the central character—Constantine the Great. Baronius looked upon him through the eyes of his apologist Eusebius of Caesarea, but also took into account orthodox and clerical corrections to the legend, according to which the first Christian emperor was baptized in Rome by Pope Sylvester, and that the popes’ secular authority and their royal prerogatives date back to Constantine’s imperial grant. It is not surprising that the volumes of the Annales, which were devoted successively to secular rulers and to Catholic pontiffs, were warmly received in the Orthodox world, and subjected only to a slight revision by the Russian hierarchs.

The union of secular and ecclesiastical authorities was as little questioned in Catholic Europe as in Eastern Christianity, and Constantine was a symbol of this union. In 1630, Jean Morin, priest of the Oratory, wrote his Histoire de la délivrance de l’Église chrétienne par l’empereur Constantin, et de la grandeur et souveraineté temporelle donnée a l’Église romaine par les rois de France (History of the Liberation of the Christian Church by the Emperor Constantine, and of the Temporal Sovereignty Granted to the Roman Church by the Kings of France), in which he rebutted Baronius, and disputed the fact of Roman baptism and the reality of Constantine’s gift—but all this only in order to claim that the emperor had been converted and had seen the heavenly cross in France, that he had been catechized under French bishops, and that it was the French kings who are the only initiators of the greatness and temporal power of the Holy See.

Ultramontanism and Gallicanism had different goals, but followed almost the same line of in interpreting the beginnings of the Christian Empire. It would take a long time before the Lutheran movement seriously threatened the Constantinian myth; which happened when criticism of the very foundations of “political Christianity” led, in Protestant countries, to the condemnation of caesaropapism. The sharp-eyed detective Santo Mazzarino noticed that a certain Johann Christian Hesse defended at Jena. in 1713. a thesis with a very telling subtitle: “On the Difference between True Christianity and Political Christianity.” And that’s where it all began. From then on, Constantine always served as a scarecrow. He, they say, chose Christianity ex rationis politicis, “for political reasons,” and made it serve the interests that he considered to be his own.

Next the baton was taken up in a book by Jacob Burckhardt, who in 1853 [Die Zeit Constantins des Grossen] rendered judgment on this false Christianity in the service of power; under his pen Constantine’s “psychological portrait” came out even harsher. The historian reproached the emperor for insidiousness and shamelessness, and Eusebius for concealing the truth. As a Western humanist and typical Protestant, Burckhardt believed that between religion and power there could be nothing but a constant friction; he rejected all forms of state Christianity and wrote against it; he was obviously antipathetic to what he called “Byzantinismus” [“Byzantinism”] which was soon to be called “Caesaropapismus.” He likened it to Islam, thereby expelling it from Europe. Historical interpretation played on all possible moral oppositions: between sincerity and opportunism, between religion and politics, between Church and State, and, in the end, between West and East.

In the same manner was the later shift from a moral critique of “political Christianity” to a more fundamental critique of “political theology.” To describe and eradicate this perversion was the task of Erik Peterson in in his brilliant essay, “Monotheism as a Political Problem,” which he published in Leipzig in 1935, under the conditions of Nazi Germany. He wrote about the dangers of monolithic and charismatic power. The reader immediately grasped the allusions that the author himself later revealed in 1947, well after the disaster. Constantine receded into the background and the proscenium was now occupied by Eusebius of Caesarea: the theologian, historian and panegyrist was now turned into a dangerous ideologue (and was disqualified as such), who wanted to make Christianity a continuation of Alexandrian Hellenistic-Judean philosophy and integrate it into Roman history. The notion of divine monarchy as developed by the Arian Eusebius and refuted by trinitarian dogma, was to be interpreted not as a theological reaction to the issue of deity, but as a political reaction to the threat of the demise of the imperium romanum. This is why the delusion of Eusebius is revealing, which is why his rejection of the proclamation of God as simultaneously one and threefold, which took the religion of Christ beyond the boundaries of Judaism, was so liberating. By so doing, it was forbidden to transfer to secular power and to the secular world models of Christian monarchy and “peace,” which could not be other than in the Godhead.

The false eschatology of Eusebius, who exaggerated the importance of the Empire in salvation history, Peterson contrasted with the distinction of the “two cities.” His preference is made all the more evident by the fact that he dedicated his book to the Blessed Augustine. He thus sketched the contradiction, which others would later develop with far less subtlety, between the East, secretly Arian and totalitarian—and the West, which had managed to get rid of political theology brought on by monotheism, and thereby destroyed all grounds for the contamination of the religious with the political.

Erik Peterson was neither the first nor the last in the line of those who made the connection between Arian “subordinatism” and the ideal of a monarch who, like the Byzantine emperor, receives directly from God both the anointing and the covenant to lead His people to salvation. But Peterson was the only one who, departing from this historical perception of caesaropapism, clearly dating back to the fourth century, made a general condemnation of any political speculation based on Christian theology. In 1969-1970 he was critiqued by Karl Schmitt whose text, both confusing and harsh, is not very convincing in which he argues about history and which is more interesting when he demands the sociologist’s right to investigate the process of secularization of Christian concepts and models.

Many historians, whether they have read the 1935 essay or not, assimilated the same perspective and turned Eusebius, whose Arianism was, we note, condemned, into the inspirer and mouthpiece of “Byzantinism,” i.e., caesaropapism; and in so doing they take at face value the opposite myth of the cynic Constantine and contrast the Western “mentality” to the Eastern one. Thus, it seems reasonable to speak of a sequence, from the Reformation to Burckhardt and Peterson (although the latter converted to Catholicism). In this perspective, the concept of caesaropapism is built on a critique of all religious authority; the debunking of “political Christianity” and the defeat of any “political theology.” At the same time. it is difficult to name beyond the university walls the source of this historiographic direction (distinctly French, sometimes tinged lightly with Catholic anticlericalism) that has arrived at a similar result, from an analysis of “modernity. No doubt, it took as its starting point the last chapter of Fustel de Coulanges’s La cité antique (The Ancient City) written in 1864, which set out to demonstrate how Christianity had “changed the conditions of government” and “marked the end of ancient society.” The historian insisted on the universality of the religious idea, which severed the connection of cults to family and polis, as well as the interiorization of faith and prayer which released the individual and allowed him to realize his freedom. What had been the privilege of a tiny elite of Stoic philosophers—the distinction between “private virtues and public virtues”—became the domain of all mankind. [Christianity] preaches that there is nothing in common between state and religion; it separates what throughout antiquity has been mixed. It must be observed, however, that for three centuries the new religion lived absolutely outside the limits of any activity of the state, able to do without its patronage and even to struggle against it—these three centuries dug a chasm between the domain of government and the domain of religion.

Since the memories of this glorious era cannot fade away—the distinction has become an indisputable truth—which even the efforts of some of the clergy cannot shake. History thereby recognizes a certain role in the separation of secular and clerical powers, the function of a certain inhibition is attributed to the church hierarchy, but as a whole is explained by the first principles of Christianity which laid a natural, non-religious foundation for law, for property and for the family; these principles are what has drawn the boundary “which separates ancient politics” from “from the politics of modernity.” With a fervor that led to accusations of his “clericalism,” Fustel de Coulanges briefly jumped through the centuries, leaving others to investigate in detail the phenomenon of caesaropapism, that remnant of antique paganism in the Eastern Christian Empire, the transformation of which was slow and incomplete.

These few pages from La cité antique had nearly the same impact in France as Burckhardt’s book had had in Germanic countries. They have been quoted in many articles and studies on the relations of Church and State. The teacher’s ideas were picked up and developed especially by one of his pupils, Amédée Gasquet, in 1879, in his doctoral dissertation, De l’autorité impériale en matière religieuse à Byzance (On the Power of the Emperor in Religious Matters in Byzantium), which he dedicated to “Academician Mr. Fustel de Coulanges.” The scientific apparatus of this dissertation is somewhat weak; but the mode of expression is sustained in the spirit of academic propriety—the author carefully avoids using the term “caesaropapism.” In any case, the intent of the work is quite clear—”ancient societies,” explains Gasquet, referring to La cité antique, which by that time had already gone through five or six editions, “did not know the division between political and religious power.” The Christian emperors of Byzantium, without renouncing any of the prerogatives of their pagan predecessors, claimed a dominant position not only in the secular but also in the ecclesiastical community; and in so doing they flaunted the title priest-king, and claimed holiness just as the pagan emperors had made the claim to apotheosis. Having embraced Christianity, they were confident that they could reform it at their own whim and adapt to their imagination “the immutable text approved by the Great Councils.” But Rome staged against the Caesars a grandiose revolution, which consisted in the separation of powers; “the pope, the vicar of Christ, deprived the imperial majesty of that power which did not belong to the title.” In the midst of this constant struggle and upheavals caused by the “caprices of the eastern rulers,” “the center of the universal church shifted from Constantinople to Rome.” The contradictions were aggravated. The pope “as a result of a bold usurpation,” began to distribute crowns in the West to those loyal to him. Thus, a political schism took place, soon followed by a religious one. Hence came the modern world, divided into those who remained faithful to the Byzantine tradition, and those who accepted the separation of powers and the supremacy of the spiritual over the secular. This division, boldly carried to its extreme consequences, was the principle which “awakened the Western nations, which grew, dwindling in barbarism.”

Consecration does not necessarily imply assent and patronage, and there is no guarantee that some of Amédée Gasquet’s assertions would have been fully endorsed by Fustel de Coulanges. But it is well to see how a generally fair idea of the inherent distinction between the spiritual and the temporal in Christianity could give rise to the false idea that this was a distinction between “two powers;” and how the image of the modern world, born of such a division, prompts one to declare “caesaropapism” a pagan legacy, preserved in the stagnant East, from which the liberated West quickly separated itself. The term, conciliatory or provocative, is not the least important. The image of an emperor scarcely washed of his paganism and all too used to playing the pontifex maximus runs through virtually all subsequent historiography. To pay tribute to Peterson, it is usually added that the ideology of the Hellenistic king, skillfully applied by the heretic Eusebius of Caesarea to a Christian monarch, served as a mediator and gave an appearance of new religious legitimacy to the successors of Augustus. But the conclusion, whether declared or implied, is always the same: Constantine’s conversion did not lead to a profound Christianization of the Empire; where imperial tradition survived, namely in the East, power remained secretly pagan. This is what polemical literature has always tried to convince the reader of, whether in the days of iconoclasm or the Union of the Churches, to cast as tyrants, persecutors and Antichrists this or that Byzantine emperor, who donned his religious role and tried to uproot the remnants of paganism from the Church.

The more “Romanesque” tradition in historiography makes some important adjustments to this scheme. The abbot Luigi Sturzo, in his book widely circulated in France, takes as his point of departure “the novelty of Christianity in comparison with other religions;” that Christianity had “severed any binding connection between religion, on the one hand, and family, tribe, nation or empire on the other, and also established a personal basis for these connections.” “For the Christian,” he continues, “there was an inherent dualism between the life of the spirit—and the worldly life, the religious and supra-worldly tasks of the Church—and the earthly, natural interests of the State.” But If unification is always harmful, the diarchy, “sealed in facts,” corresponded not so much to the separation of powers, but to their mutual accommodation. “From the Edict of Constantine and up to the formation of the Carolingian Empire, two types of religious and political diarchy developed: the Byzantine Caesaropapist and the organizing Latin.” The first represented “a political-religious system in which the power of the State became for the Church an effective, normal and centralizing power, though external to it; a system in which the Church participated in the exercise of certain worldly power functions; and in a direct form, though not independently.” Such was the position of the Eastern Church after Constantine, which led to a loss of autonomy, to subordination to the State, to the preservation of the economic and political interests of the secular elite and the privileged caste of clerics. In contrast, in the “Latin organizational diarchy,” “the Church, while constantly calling on the aid of the civil authorities and constantly ceding to the rulers some powers, some opportunities and some privileges within the ecclesiastical body, nevertheless almost always protested against any real dependence on them and, when necessary, insisted on its independence.” The author goes on to analyze in detail the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, the development of national Christian churches, and the politics of the “concordat.” Of course, he fails to draw a line down the centuries between the mixing of powers inherited from antiquity and their differentiation as an innovation of Christianity. However, he draws a distinction between the Eastern model (modern rather than medieval)—and the Western model, which, a better knowledge of the subject, permits him to present in a more nuanced way.

The nuances give way to polemics in literature which more openly declares its confessional character; one of its most recent representatives is Fr. Martin Jugie a great connoisseur of the East, but also a great persecutor of schismatics: “Caesaropapism, as the term itself shows,” he writes, “means a State where civil power, Caesar, substitutes himself for the pope in exercising supreme power over the Church; this is—a totalitarian state, arrogating to itself absolute power both over the mundane and over the sacred, both over the earth and above, practically ignoring the separation of civil and spiritual powers, and at the least subordinating the latter to the former.” The roots of this evil stretch back to the pagan past: “The pagan empire was Caesaropapist in the full sense of the word. It was unfamiliar with the distinction between the two powers. The pagan emperor, who was called summus pontifex, possessed both the fullness of the priesthood and the fullness of authority over the clergy and over sacred matters. This absolute caesaropapism is incompatible with the Christian religion, in which we find a hierarchy endowed with special liturgical powers inaccessible to the laity… The head of the Christian State cannot be analogous to the Roman Pope, for he never had the authority of an ecclesiastical person. He can only usurp the role of the pope in the Catholic Church.” Such invasions have occurred frequently. “But it was in the East that caesaropapism was given a green light; it happened as early as the fourth century, the day after Constantine declared himself the patron of the Christian religion…. The pernicious example set by the first Christian emperor was followed by his successors, especially those who, after the division of the empire into two halves, ruled the eastern part… It is true that imperial caesaropapism often served the interests of the Church… But in terms of the unity of the Church it has had disastrous consequences: such are the nationalization of the Church, the enslavement of the clergy, the muted or open hostility to the popes… Unlike the Western Church, which, in spite of temporary abuses, found in the popes staunch defenders of its independence, the Byzantine Church had very few such fighters, although they were not absent altogether. On the whole, the eastern episcopate showed itself very obedient to dogmatic antagonisms and political heresies of their emperors.” Here we have a really well-stuffed bag of prejudices that, under the influence of the spirit of ecumenism and simple historical objectivity, are somewhat out of fashion and no longer in vogue, even in clerical circles.

The spread of the term “caesaropapism” is of course on the conscience of Roman Catholicism, but reformist Russian Orthodoxy also had a hand in this. In the last decades of the 19th century, Vladimir Solovyov debunked tsarist absolutism and its claims that the Eastern Church “itself gave up its rights” to hand them over to the State. He especially blamed the Syriac Orthodox Church for having become “a national church” and therefore losing the right to represent Christ, to whom all authority on earth and in heaven belonged. “In all countries, the church is relegated to the position of a national church,” he wrote, “and the secular government (whether autocratic or constitutional) enjoys the absolute fullness of all power; the ecclesiastical institutions appear exclusively as a special ministry, dependent on the general state administration. Here again it was pointed to Byzantium, which in the ninth century (in other words, during the time of Photius) claimed to be the center of the universal Church, but in reality gave the impetus to the deviation to nationalism.” Even closer to the present day, Cyril Toumanoff put across the same point of view—according to him the “Byzantine evil” consisted in the absence of a clear distinction between the spiritual and the temporal, in the predominance of the latter over the former, and in “Caesar taking responsibility for divine matters.” In this perspective, he described Russia as a “provincialized and barbarized Byzantium,” noting in passing the fusion of caesaropapism “à la Rousse,” with Protestant ideology, which seemed important to him. This time the problem shifted; and if we are still talking about pagan survivals in the Constantine Empire, now the birth of caesaropapism was attributed to a “later time,” the period of schism and the explosion of “Greek” nationalism, as opposed to Christian universalism.

In response to these many attacks, the wounded “Orientals,” whose beliefs and whose concern for truth had been questioned, attempted to offer resistance. It was not too difficult for them to introduce significant nuances to this black picture of retrograde “Byzantinism,” and to show that “caesaropapism” was a flawed word, an anachronism, incorrectly projecting to the East the Western notion of the papacy, and to the Middle Ages—the concept of separation of powers—applicable only to the New Age. Byzantium never denied the distinction between temporal and the spiritual, never officially allowed that the emperor could be a priest; those autocrats who ventured to suggest such a thing were regarded as heretics, and those who encroached on ecclesiastical rights (or, worse still, on ecclesiastical wealth) were branded as sacrilegious. So goes the rebuttal. But historians have also tried to make a distinction. They said, the interventions of the Empire in the affairs of the Church should not to be lumped together: some of them were permissible (the right of the emperor to summon and preside at councils; the promulgation of laws and canons; the maintenance and modification of the church hierarchy); others were reprehensible (the appointment of bishops; the formulation of the creed).

The global disapproval of Byzantine practice was casuistically dissected thus: The Byzantine emperor did not go beyond his powers if he was content to enforce canons or conciliar decisions; he went only a little beyond these limits when, on his own initiative, he passed laws concerning the Church, if they were in accordance with her own wishes (as Justinian and Leo VI had done in their Novels); the emperor was allowed a harmless violation when he imposed his personal preferences on the Church with her consent—but when he did the same not only without consultation, but sometimes with a minority of bishops against their majority, especially in matters of faith, then this was a flagrant abuse. Only the last two cases were attacks on the independence of the Church—the first two, although based on the same legal principle, at least respected the rules of the game.

Theologians or canonists have always been less tolerant than historians—but they oppose actual interference with a legal division written in the canons and constantly commemorated. They sought and found those responsible for the perversion: the authoritarianism of Constantius II (so as not to offend the inviolable Constantine); the Justinian mania for lawmaking; the “imperial heresy” of the iconoclasts, or the “Scholia” of Balsamon—all of which flirted with the concept of a quasi-priest emperor. Interpretation of canonical heritage, given at the end of the 12th century and taken up by Matthew Blastares, absorbed this stable tradition without any rethinking. Even though there was a deviation, the position of the Eastern Church was not (or was not always) conciliatory; it had to fight the “paganism” that persisted in the imperial ideology. How late it remained there is evidenced by titles like “epistemonarch” or “intercessor.”

At any rate, the word “caesaropapism” is annoying. It sounds like a slap in the face. It is attributed to the “Latins,” without realizing that the physical evidence for the accusation was fabricated throughout the Byzantine Middle Ages. Given the charge of Eastern caesaropapism, an accusation of Western “Papotsarism” is made. On the whole, this is a weak objection: it drags one into a polemic—when what is required is an analysis of the mechanisms, as suggested in our brief historiographical review.

In any case, of course, Byzantium itself is “not without sin;” but of it was made a scapegoat. In the artificially constructed concept of caesaropapism is a mix of contradictory elements. At its inception, Roman fundamentalism entered into a strange alliance with the spirit of the Reformation; the radical distinction between the spiritual and the temporal, which was supposed to purge religion from politics, curiously led to the recognition of the “authority” of the clerics; the founder of the Christian empire was blamed for lack of secular ideals. It is clear that Europe cannot understand medieval Byzantium— this is not allowed by European history, geography and culture.

Without going into detail, let us recall a few obvious truths. The opposition or dialogue between “Church and State” is possible only for a secular power, more or less irreligious and confined to the framework of a single state, and for the Church, identified with its clergy. This opposition reveals the originality of the Christian Empire: its universality (at least theoretically), its place (as a political structure, as a society, and as a historical phenomenon) in the divine government, centered on it, with all its ruptures, with all its reversals, with its past and especially with its completion. The rupture? And what else can one call the Incarnation of Christ, by which the coming of the age of Grace was heralded in the midst of a political regime pleasing to God—for the Empire of Augustus was chosen as the cradle for the new religion. Return? What else was the curious projection of the Jewish past onto the Christian present, when Byzantium and its emperors lived as if on two levels, the level of Old Testament models, read as “images” from the Christian future, and the level of Christian history, which was nothing more than the realization of these “images.” Completion? This is a programmed end, as announced by Daniel and all the Apocalypses, because of it. Christian time, since the reign of Constantine, has become a “countdown.” Within this timeframe, empire is presented as a setting, and the emperor as the principal actor. Notions of “this age,” “the State,” or “worldly power” are useful for delineating the domain of imperial institutions in contrast to the institutionalized Church, handed over to the cares of the clerics. But these same concepts ignore the aforementioned alchemical transformation of time, this sacred history, within which the emperor was something like a High Priest. Back in 1393, Patriarch Anthony IV of Constantinople reminded Prince Vasily of Moscow about the role of emperors in the formation of Orthodoxy, about the unity of the empire and the Church. The idea of two separate powers is not prerogative; but this is where it took the “modern” form, the form of the political revolution that accompanied the separation, later the collapse, of the empire in the fourth and fifth centuries.

In the East, the reaction was neither so rapid nor so unequivocal. The dispute was accompanied inexorably by vestiges of messianism and the expectation of an eschatological denouement. Although the emperors seldom dared to publicly proclaim their priesthood “according to the order of Melchizedek,” they still believed in their special mission: to dispose of that double heritage, Davidic and Levitical, which Christ declared to be His, having come into the world in the flesh, during the first “advent,” but which He will enter into possession of, having finally established His kingdom, when the end of the world, called the second “coming,” will soon come. The royal priesthood in Byzantium was a continuation of the messianic spirit during that interval between the two “comings” which exactly corresponds to the period of the Christian Empire.

Needless to say, in this matter (as in all others), history does not decide who is right and who is wrong. It only allows us to understand past justifications and measure the bias that has been created to date by any history that has become a tradition, and then any tradition that has become an ideology. The West, for which Judaism played almost no role as the main standard and which grew up on the ruins of the Empire, made valor out of necessity. The West underestimated and dismantled that majestic building, which was the result of the meeting of two traditions, Roman and Jewish. It divided the “authorities” in order to create a spiritual power in the backyard of modern states, which was often nothing more than a powerless theocracy. As for the East, it prolonged that grandiose and fruitless dream which was already illusory in the Empire of the Second Rome, a dream which served as an alibi for the retrograde autocracy in the Russian Empire of the Third Rome and which in today’s world often appears under the ugly mask of nationalism. The political aporia “priest and king,” “priest or king” is undoubtedly one of the basic problems of mankind, and its solutions in history grow out of each other in the process of mutual adaptation of cultures.

In conclusion, let us give the floor to Dostoevsky. In one of the first chapters of The Brothers Karamazov, the most Byzantine of his novels, Dostoyevsky sets forth, in the form of a paradox, the problem we have been discussing here. Ivan Karamazov, an intellectual revolutionary and atheist, has written a treatise on church tribunals in which he denies the principle of separation of Church and State. He is questioned about this by the participants in the conversation, who embody the entire spectrum of opinion: Miusov, a secular man, landowner, Westerner, and skeptic; Father Paissy, a worthy representative of Orthodoxy; and an elder who speaks his heart. Ivan justifies his position by explaining that the mixing of Church and State, intolerable in itself, will always exist because there can be no normal relationship between them, “because lies lie at the very heart of the matter.” Instead of asking about the place of the Church in the State, we should instead ask how the Church is to be identified with the State in order to establish the kingdom of God on earth. When the Roman Empire became Christian, it naturally included the Church; but the Church, in order not to renounce its principles, must in turn seek ways of gaining control over the State.

Miusov observes that this is a trivial utopia, “something like socialism.” The elder hesitates for another reason: he fears that in a world where law and love will merge, the criminal will no longer have the right to mercy, as he believes there is no such right in “Lutheran countries” and in Rome, where the Church has proclaimed itself the State; and yet he foresees the distant day when the Church will revive. “What is this really about,” exclaimed Miusov, as if suddenly bursting out, “is the State being eliminated from the earth, and the Church being elevated to the degree of a State. It’s not just ultramontane, it’s arch-ultramontane! This was not even imagined by Pope Gregory VII! Quite the opposite of what you mean!—Father Paissy said sternly.—It is not the Church that turns into a State, understand that. That’s Rome and its dream; that’s the third devil’s temptation! On the contrary, the State converts to the Church, ascends to the Church and becomes the Church in all the earth, which is quite the opposite of both Ultramontaneism and Rome and your interpretation, and is only the great destiny of Orthodoxy on earth. From the East the star shall shine forth” (The Brothers Karamazov, Part 1, Book 2, Chapter 5).

Such debates were waged in Russia in the 1870s-1880s. They somewhat confused the concepts of theocracy and caesaropapism. Here the ideological costs of the church-state may have been anticipated, but they were generally found to be more consistent with the spirit of Orthodoxy than the spiritual betrayal the church-state seemed to represent. The one point on which all agreed was the recognition that the fundamental separation of the two powers rested on a lie.

Gilbert Dagron (1932-2015) was a foremost scholar of Byzantine history, whose best-known work is Emperor and Priest: The Imperial Office in Byzantium.

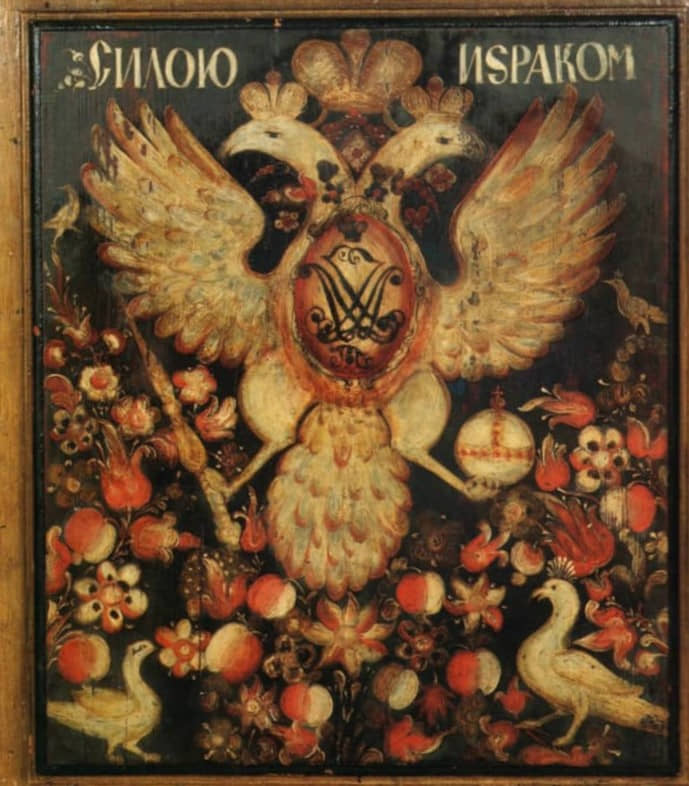

Featured: Double-headed Eagle, anonymous, from Filenka, ca. 1740s.