In this year (2022), René Guénon’s work enters the public domain. It is on this occasion that, after having passed from the collection “Tradition” to the pocket format at Gallimard, the beautiful editions of the publisher Allia has chosen to bring back The Crisis of the Modern World in an elegant cover and design. Elegance suits Guénon who, before being a metaphysician, was recognized by his detractors as well as by his disciples as a writer of genius, distinguished by his perfect mastery of the French language. To read and reread Guénon is, in this sense, to learn to think. Guénon distinguished himself in the great debate concerning the relationship between the East and the West, and recognized as a “literary” motive by Brasillach, that privileged observer of the inter-war society.

Also, Guénon, whom Raymond Queneau read assiduously, was compared by this great name of surrealism to the novelist Marcel Proust, for the obvious reason of style. In 1927, Guénon had already adopted a “pure language;” by this “resorption of the individual person in language,” explained Emmanuel Berl in 1953, the hermit of Duqqi had gained that literary immortality to which Proust aspired. Thus, by his style, as much as by his content, even to the deliberate use of the royal “we” characteristic of his writings, Guénon, through the usual requirements of French, elevates literature to the impersonality of myths.

This literary immortality began with the success in the marketplace—at the time of the publication of The Crisis of the Modern World, André Thirion tells us that the book was known without even being read. However, if this book sold like hotcakes, it must be said that, beyond the ephemeral scene of the world, it is, like the “hotcakes” of heaven present on the altar, a care of the soul for whoever reads it. It does not heal the soul as medicine can heal the body, by making it forget its symptoms of pain—rather, like the religious examination of conscience that precedes the taste of the transubstantiated bread, it purifies the modern soul by showing it its ills.

Individualism

In The Crisis of the Modern World, Guénon explains that Western intellectuality and society are corrupted by abnormal deviances, and opposed to the traditional order that was the order of the Western Middle Ages and of the East as a whole. At the same time, he explains, the intellectual crisis of the modern West is rooted in “individualism,” which he defines as “the negation of any principle superior to individuality.” This mental attitude characterizes modern thought as an error or a false system of thought. In fact, individualism, from the point of view of knowledge, consists in refusing to recognize the existence of a “faculty of knowledge superior to individual reason;” while, from the point of view of being, it is a “refusal to admit an authority superior to the individual.” This close link between knowledge and authority is explained by the fact that Guénon understands tradition in its most purely etymological sense—as a deposit which, being transmitted (tradere in Latin), is not invented, but received, and which, for this reason, does not come originally from the human being by innovation, but from the supra-human by revelation. Tradition is thus sacred by definition, according to Guénon, who distinguishes it clearly for this reason from simple custom—to deny the sacred or divine foundation of tradition is to deny that which legitimizes its authority.

Thus, the first form of this negation, in the order of knowledge, is characterized by “rationalism;” that is to say by the “negation of intellectual intuition” and consequently by the fact of “putting reason above everything.” The ancients, from Plato to St. Thomas Aquinas, Plotinus and St. Augustine, taught the existence, above individual human reason, of a synthetic faculty of knowledge belonging to the mind, through which the universal principles of being and knowing are intuitively grasped. In contrast, the Moderns ceased to recognize the existence and efficiency of the intellect, and confused it, from Descartes onwards, with reason; up till now considered as a human and individual faculty of discursive knowledge, belonging to the soul in its investigation of the general laws of nature. The movement initiated by Descartes was to be confirmed with Kant who, reversing the hierarchy, placed the intellect below reason in the form of understanding and declared “unknowable” the traditional objects of the intellectualist metaphysics of yesteryear, in the first rank of which is God.

Rationalism and Free Inquiry

This negation of intellectual intuition explains the passage from the traditional sciences to the modern ones: “The traditional conception,” writes Guénon, “attaches all the sciences to principles as so many particular applications, and it is this attachment that the modern conception does not admit. For Aristotle, physics was only ‘second’ to metaphysics; that is to say that it was dependent on it, that it was basically only an application, in the field of nature, of the principles superior to nature and which are reflected in its laws; and the same can be said of the ‘cosmology’ of the Middle Ages. The modern conception, on the contrary, claims to make the sciences independent, by denying everything that goes beyond them, or at least by declaring it ‘unknowable’ and refusing to take it into account, which again amounts to practically denying it.”

What happened in the order of the sciences was thus happening with regard to religious authority; for individual reason, no longer recognizing a superior faculty governing it, claimed to substitute itself for the expertise of the Church in matters of faith, through the Protestant practice of “free-examination.” “It was thus, in the religious domain, the analogue of what was to be ‘rationalism’ in philosophy; it was the door open to all discussions, to all divergences, to all deviations; and the result was what it was to be—the dispersion into an ever-increasing multitude of sects, each of which represented only the particular opinion of a few individuals. As it was, under these conditions, impossible to agree on doctrine, it soon passed into the background, and it was the secondary side of religion, we mean morality, which took the first place: hence that degeneration into “moralism” which is so noticeable in Protestantism today.”

Materialism

The negation of intellectual intuition has, according to Guénon, far more tangible and far-reaching consequences than ruptures in the theoretical domain. Practically, in fact, it is the conception of human nature and of its place in the universe that is involved—if Man is no longer capable of seeing intellectually and of communing spiritually with supernatural realities, he naturally (and how can we blame him?) limits his life and his ideals to all that pertains to the material plane of existence: “so he strives, by all means, to acquire what can provide all the material satisfactions, the only ones he is capable of appreciating; it is only a question of ‘earning money’… and the more one has, the more one wants to have more, because we are constantly discovering new needs; and this passion becomes the sole goal of life.”

Guénon thus analyzes the numerous aspects which constitute the “materialism” which is constitutive of modern civilization, and which Guénon defines at the same time, in its criticizable form, as “a conception according to which there is nothing other than matter and that which proceeds from it,” and as a state of mind which gives “the preponderance to things of the material order and to the concerns which relate to them.”

As Saint Thomas Aquinas says, quantity is the signature of matter, only the force of numbers counts everywhere in the modern world. This explains productivism, by which industry, instead of being an “application of science,” as it should be, is systematized and becomes its “raison d’être and justification.” In this context, Guénon also notes “the immense role played today by industry, commerce, and finance,” and considers, from an international point of view, that any economic agreement based on commercial interests, unlike spiritual agreement based on metaphysical principles, can only be ephemeral and insufficient. The reason for this is that “matter, as we have already said many times, is essentially multiplicity and division, and therefore a source of struggle and conflict; therefore, whether it is a question of peoples or individuals, the economic domain is and can only be that of rivalry of interests.”

This is why neither the League of Nations nor even the United Nations Organization prevented the outbreak of numerous modern wars, which are also defined by the force of numbers, as evidenced by the phenomena of the “armed nation,” “mass mobilization” and “general mobilization” (Guénon was a contemporary of the two world wars). In the more purely political order, democracy is also related to materialism and its reign of quantity, because it is still “the opinion of the majority which is supposed to make the law.” Thus, we use the very physical and material term of “mass” to designate the new form that the community takes in the modern era. Finally, in the order of popular values, Guénon points to the Anglo-Saxon idealization of sport and its “athletes,” instead of the saints and heroes of the past.

In short, whatever the field considered in modern civilization, “there is no more place for the intelligence nor for all that is purely interior, because these are things which cannot be seen nor touched, which cannot be counted nor weighed; there is only place for the external action in all its forms;” action which “degenerates thus, by defect of principle, into a meaningless, vain and sterile agitation.”

Reform of the West

Guénon’s implacable critique of the modern world is no less uncompromising with regard to the different forms taken by the traditionalist thoughts of his time. Indeed, the survival of the Western world in its modern phase depends on the quality of the solutions that one proposes to bring to it, which implies a high requirement on the side of anti-modern thought. Thus, Guénon opposes the various forms of reactive traditionalism to oppose an affirmative or reforming traditionalism, which defuses any unsuccessful reactionary attitude.

Thus, against a certain religious traditionalism, Guénon opposes most apologetic enterprises. “The ‘apologetic’ attitude,” he writes, “is, in itself, an extremely weak attitude, because it is purely ‘defensive,’ in the legal sense of the word; It is not for nothing that it is designated by a term derived from ‘apology,’ which has for its own meaning the plea of a lawyer, and which, in a language such as English, has gone so far as to take commonly the meaning of ‘apology;’ the preponderant importance given to the “apologetic” is thus the unmistakable mark of a retreat of the religious spirit.”

In the political realm, Guénon, who historically prefers the feudal system to the national system, also attacks the nationalism of Action Française, whose traditionalism is mutilated by an idolatry of the nation, a specifically modern political form, affirmed in the 19th century as a consequence of the French Revolution: “the constitution of the ‘nationalities’ [is a] consequence of the destruction of the feudal regime, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, of the simultaneous break-up of the superior unity of the ‘Christendom’ of the Middle Ages.”

In the cultural order, finally, Guénon sums up his entire alternative by opposing the “Defense of the West” advocated by Henri Massis against the East in 1925, a “reform of the West” responsible for defending the West against its own modern tendencies which threaten to destroy it.

The “reform of the West” advocated by René Guénon consists “in restoring something comparable to what existed in the Middle Ages, with the differences required by the modification of circumstances,” because “it is in Christianity alone, let us say more precisely in Catholicism, that the remains of the traditional spirit that still survives in the West are to be found.”

However, this Catholic restoration that Guénon calls for in 1927 must not be reactive and exclusive of other cultures and doctrines, but on the contrary it must be confident and virile in its rapprochement and resourcing with the traditional doctrines of the East, in the double perspective of a great front of traditional piety and spirituality. “A contact with the fully alive traditional spirit is necessary to awaken what is thus plunged into a kind of sleep, to restore the lost understanding; and, let us repeat once more, it is in this above all that the West will need the help of the East, if it wants to return to the consciousness of its own tradition.”

Paul Ducay, Professor of philosophy with a medievalist background. Heir to the metaphysics of Nicolas de Cues and the faith of Xavier Grall. Gascon by race and French by reason. “The devout infuriate the world; the pious edify it.” Marivaux. [This article comes through the kind courtesy of PHILITT].

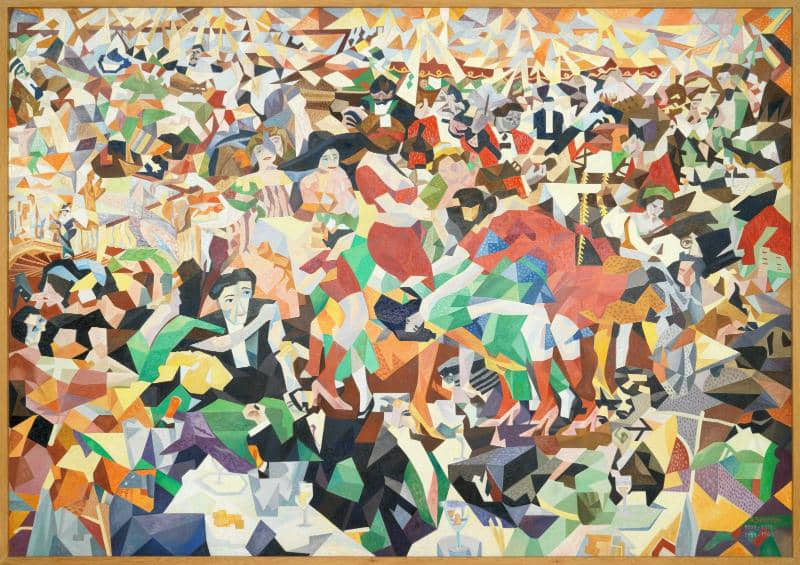

Featured: “La Danse du Pan Pan au Monico,” by Gino Severini; painted ca. 1909/1960.