Chairs and benches are for sitting, beds and couches for sleeping and resting, chests and wardrobes for storage. Furniture may also be thought of as an indicator of social status. The chair has long been used symbolically to express authority and rank. Commoners were expected to sit on stools. But while standard histories of furniture emphasize the utilitarian and hierarchical nature of furniture, including changes in building techniques, they recognize that furniture provides a mirror into the aesthetic standards and cultural creativity of different societies, in different times.

Edward Lucie-Smith’s Furniture: A Concise History (1979) agrees with this basic way of examining furniture, while also trying “to show how furniture is related to the general development of society, and to the psychology of the individual” (12). But other than showing how a more urbane bourgeois life promoted modern attitudes towards furniture design, leading to a greater emphasis on comfort, away from the “stiff style” of the royal courts and aristocracies of Europe, and to new types of furniture constructed with industrial materials and technology, Lucie-Smith fails to apprehend how his emphasis on “the general development of society” is itself a unique product of the very European culture his book is almost entirely about. Apart from dedicating half a chapter to “Ancient Egypt” and “Western Asia”—along with Greece and Rome—the next eight chapters of his book are singularly about Europe. Why?

If pressed today, Lucie-Smith would apologize for his “Eurocentrism.” He can be faulted, to be sure, for ignoring such major civilizations as China, Japan, and India. Yet even more recent books that try to meet multicultural standards dedicate most of their chapters to European furniture.

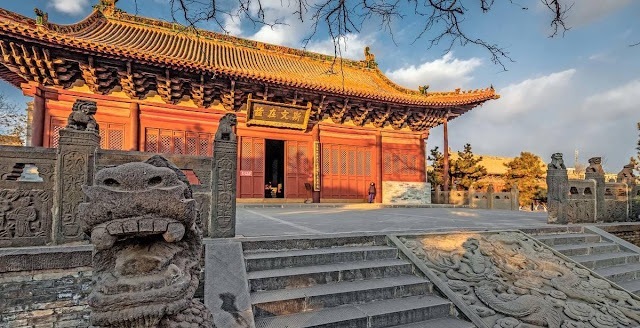

Judith Miller’s Furniture: World Styles from Classical to Contemporary (2010), which covers more than 3000 years of furniture design in over 500 pages, packed with illustrations, dedicates a few pages to “Ancient Egypt” and “Ancient China,” with a few additional pages to India, Japan and China in the nineteenth century. Miller recognizes the aesthetics of furniture-making in these cultures, while implicitly noticing that once these civilizations created certain ideals in furniture design and decoration, these types remained in “continuous use” for centuries with slight variations until the West impacted them in the nineteenth century. She observes that the “golden age” of furniture production that was witnessed in the Ming era (1368-1644), with its ideal of “simple furniture with clean lines and sparse decoration limited to lattice work and relief carving,” would “remain entrenched” through to the entire Qing era (1644-1912), except that furniture pieces became larger and heavier (pp 24-5).

One gets the impression that the authors of furniture histories, and the related subject of interior design, believe it is only natural to focus primarily on Europe—because the historical reality, the images, drawings, and documentary evidence we have, demonstrate that Europe saw a continuous sequence of changing styles. A proper aesthetic assessment of these styles requires separate chapters and explanations. Authors don’t feel they have to justify their implicit Eurocentrism. It comes naturally to them, on the strength of Europe’s creativity. Conversely, they feel that the persistence of similar styles in the nonwestern world, or the prevalence of one model of aesthetics, justifies giving these civilizations less attention. One of the best books on this subject, History of Interior Design & Furniture: From Ancient Egypt to Nineteenth-Century Europe, by Robbie G. Blakemore, opens with a chapter on Egypt, and then, without any hesitation, as a matter of fact and reasonableness, dedicates the next 400 pages solely to European interior design of floors, walls, ceilings, chimneys, decorative materials, tables, chairs, windows, doors, beds, storage pieces, and stairways.

I have noticed the same Eurocentric tendencies in the popular subject of architecture. A World History of Architecture by Michael Fazio, Marian Moffett, Lawrence Wodehouse (2004) informs us that their book offers a “diverse sampling” of the world’s architecture, with one chapter assigned to “The Beginnings of Architecture” in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, another chapter to “Ancient India and Southeast Asia,” one to “China and Japan,” one to “Islamic Architecture,” and one to the Pre-Columbian Americas. Eleven chapters, however, are reserved exclusively for Europe or the West generally. Similarly, Architecture: A World History, by Daniel Borden, et al., is mostly a chronology about European architecture, once it covers the stereotypical models of ancient civilizations in the opening chapters.

But we can’t underestimate the pressures of multicultural politics in the West, the lucrative incentives provided to academics who follow the official university values of “diversity, equity, and inclusiveness.” Books are increasingly coming out purposely twisting and obfuscating the history of architecture, so the European legacy stands as one among many “equally sophisticated” legacies in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. This is what A Global History of Architecture (2017), by Ching, Jarzombek, and Prakash, is about. These authors “organized the book by time slots,” according to a chronology dictated by the impact of “global events” on architecture, rather than by changing architectural styles. In this way, the authors happily give the same attention to multiple cultures in the modern era that were equally impacted by “global connections,” regardless of whether any significantly new styles emerged. What matters, the authors declare, is to see architecture from a “global perspective” at all times, the relationship of architecture to global events, including European imperialism and colonialism—”rather than viewing the history of architecture as driven by traditions and essences” (p. xii). Very clever: emphasize European global imperialism in the modern era, its effects on the nonwestern world, and thereby include this world in the modern era, and forget the reality that nonwestern architecture was indeed driven by unchanging stylistic essences.

Let’s cut to the chase. The one architect outside the West who can be named in a list of the 100 greatest architects in history (before Western culture impacted the rest of the world in the 20th century) is the Ottoman Mimar Sinan. The civilizations of the Mayans, Aztecs, and Incas saw “monumental” stone buildings, pyramids and temples, constructed at the behest of state officials, but these architectural attainments were a one-time affair in their originality, deserving only one chapter or section in a world history survey.

The architecture of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Persia is more impressive but not on the same aesthetic and geometrical level of harmony as the ancient Greek Parthenon of Athens, built in the mid-5th century BC, the Doric Temple of Zeus at Olympia (460 BC), or the Temple of Poseidon at Sounion (440 BC). It is certainly below the level of proficiency and beauty attained by the ancient Romans. Once these ancient monuments were created, less originality followed thereafter: no new epochs in aesthetics, no major architects we can identify. The same continuity we see in these civilizations in other fields—science, historical writing, philosophy, painting, mathematics, technology—is apparent in architecture.

What about Chinese architecture? It is worth quoting what Nancy Steinhardt, a major expert, tells us about architects in Chinese Architecture: A History (2019).

Most of them were officials whose service at court included directing imperial-sponsored projects, perhaps occasionally even designing, and writing about construction. The classical Chinese language has no word for “architect,” only one for a person who engages in the craft of building. Instead, from as early as written records can confirm, the final millennium BCE, in every branch of Chinese construction—public or private, imperial or vernacular, religious or secular—principles and standards established centuries earlier dictated building practices. The standards were sanctioned and guarded by the Chinese court, and the government was the sponsor of all major manuals that dealt with official architecture. Craftsmen were not required to be literate, only to follow prescribed modules and methods so as to ensure that court dictums were followed. The treatises expound a standardized system of construction that is maintained not just in imperial buildings of life and death and a towering religious monument, but in temples hidden in the mountains, houses, and shrines, and in paintings and relief sculpture of architecture through the ages (Introduction, pp. 1-7).

All the popular talk about “Chinese Garden Architecture,” “Chinese Buddhist Architecture,” “Chinese Taoist Architecture,” or “Chinese Confucian Architecture,” cannot hide the standardized, bureaucratic reality of China. As a huge country with many different ecosystems and historical settings, different stereo-typified styles emerged in different regions. I say “stereo-typified” because once these styles were established, they became ready-made models for hundreds of years.

Only Europe sees a “developmental” history. The one memorable “architectural treatise” from China was the Yingzao Fashi, published in 1103, during China’s Song Dynasty. We are told that this work (entitled “Treatise on Architectural Methods or State Building Standards”) was written by Li Jie (1065–1110), the Directorate of Buildings and Construction. He was a bureaucrat in charge of continuing the standardized pattern of construction, not an “architect” with the cultural opportunity to challenge existing aesthetic models. We learn from Fu Xinian, considered to be the world’s leading historian of Chinese architecture today, that architecture as an academic discussion only entered China in the late 1930s, through the pioneering studies of Liang Sicheng (1901-1972), educated in the West and awarded an honorary doctoral degree in 1947 by Princeton University.

The conclusion cannot be avoided that Europeans originated a continuous sequence of major architectural stylistic periods (within which there were other national styles), each deserving a chapter in a fair-minded world history.

- Classical (850 BC to 476 AD)

- Romanesque (900 to 1200 AD)

- Gothic (12th through to 16th century)

- Renaissance (14th through the 17th century)

- Baroque (late 1500s until late 1600s)

- Rococo (1700 – 1760)

- Neoclassicism (1760-1830 )

- Victorian-Eclecticism-Restoration (1815-1900)

- Art Nouveau (from 1890 to 1910)

- Art Deco (from 1915 to 1930)

- Modernism (early 20th century to the 1980s)

Furniture Making and Interior Design

Let’s get back to the main subject of this article: furniture design and interior architecture. I am no expert on this subject, but drawing my extensive research on Western civilization from a comparative historical perspective, I will surmise the following four interconnected key traits about Western interior design and furniture:

- It exhibits the greatest variety within each kind of furniture; for example, in the variety of chairs, beds, and tables, including a variety of ceiling configurations (flat, coved, or vaulted, for example), chimney pieces, stairways, and spatial relationships.

- Its artistic inspiration, creativity and originality, was driven by a Faustian will for recognition on the part of the artists, pursuit of individual renown, and a will to surpass prior accomplishments.

- Close to 100% of pre-20th century treatises (fully articulated arguments) on the principles of furniture-making, architecture, the geometric shapes and patterns of room/spaces, height and configuration of ceilings, internal arrangement of stairways, chimneypieces, were written by Europeans.

- The Platonic striving for perfection, the highest in beauty, the discovery of a “blueprint” of perfection, has been a very powerful motivation, notwithstanding the pursuit by each individual artist of his own style, and the subsequent powerful influence of technology, new materials, and mass consumerism in the twentieth century.

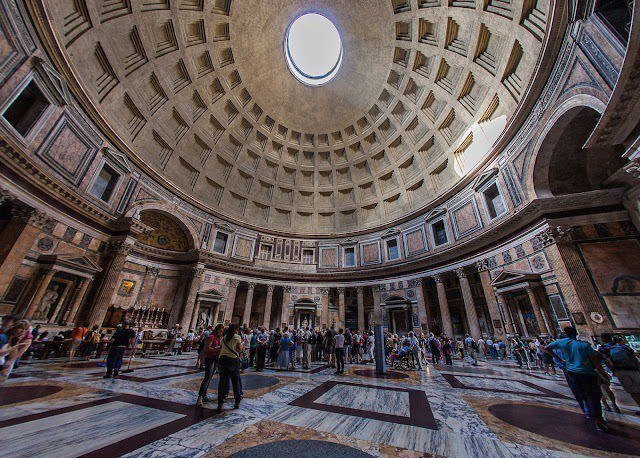

The epoch of continuous creativity in interior design and furniture making in Europe began in the Renaissance around the mid-fifteenth century. The Greeks built some of the finest architectural monuments in history, such as temples, theatres, and stadia, with their sophisticated geometrical proportions, perfectly straight lines and harmonious spatial configurations. The Romans mastered the Greek arch and vault as well as the use of domes to cover large areas with no internal support.

The Romanesque and Gothic periods in the Middle Ages were likewise very significant, but it was only in the modern era that Gothic motifs would come to play a role in furniture making and interior design. There is, of course, a strong relationship between furniture/interior design and architecture. To this extent we must mention architectural accomplishments, insofar as they had a direct impact on the history of furniture making and interior decoration of ceilings and floors, chimneys and stairways.

Renaissance

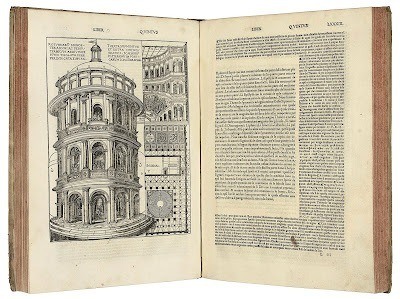

Italy was the springboard for the Renaissance in furniture making and architecture beginning in the 1400s. A critical factor was the “rediscovery” of the legacy of classical antiquity, including a treatise written by the Roman Marcus Vitrivius Pollio (80–70–15 BC), a multi-volume work entitled De architectura. This work was very influential in launching the Renaissance style, with its idea that buildings should have “strength,” “utility,” and “beauty” or perfect proportions. It inspired Battista Alberti (1404-72) to write the first architectural treatise of the Renaissance, emphasizing the layout of the interior of buildings.

Bear in mind that we are speaking about treatises—not mere descriptive guidelines—but systematic, extensively argued discourses, in which the principles of a particular subject are discussed and explained. Alberti influenced the architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), recognized for developing linear perspective in art and for designing buildings heavily dependent on mirrors and geometry, to express the highest perfection in Christian spirituality.

Antonio Averlino’s (1400-69) 21 book-treatise on architecture, and Sebastiano Serlio’s illustrated book on architecture, published in 1537-5, were both influenced by Alberti. The foremost architect of the 16th century, Andrea Palladio (1508-80), author of The Four Books of Architecture, was particularly interested in conceptualizing the function of each part of the interior of buildings in terms of their geometric form, and delineating thereby a hierarchy wherein a larger interior order would override a lesser order: the divine and perfect world of faith over the earthly world of humans.

At the same time, we should keep in mind the humanism that permeated the Renaissance, about the earthly world of humans with its emphasis on man as the highest form of creation. The Renaissance preoccupation with symmetry and horizontality, the idea that beauty was enhanced by calculating mathematical ratios, was indeed based on the measure, and actual potentiality, of the human body as a system of proportional relationships. The Renaissance employment of exact perspective to create optical illusion of three-dimensional spaces, depth and distance, played a very significant role in the unprecedented variety of decorative treatment of walls that characterized Italian interiors during the 15th and 16th centuries.

This period witnessed an unprecedented variety of wall decorations, ornately treated door refinement with classic elements, stop-fluted pilasters, pedestals, entablature. Flat, vaulted, and coved ceilings were prevalent forms with surfaces of every description. While chairs in the medieval period were rare status symbols, the Renaissance saw new types of chairs, including the sgabello, an armless back stool; the cassapanca, a multi-seat unit, which also served as a chest; the credenza, a cupboard with great variety in design; dining tables (rectangular, long, and narrow) were also introduced. And since Europe is made up of distinctive national peoples, there would be a French Renaissance with its own variations, for example, in types of materials used for floors: stone, marble, tile, brick, and wood.

The number and size of windows increased substantially in the early years of the French Renaissance; and highly ornamented chimney pieces (such as the one at Château de Fontainebleau) became the focal point of the room, with a wide variety of decorated panels, carved relief designs, and freestanding statues. The caquetoire chair was introduced around the mid-16th century, a lightly scale wooden chair with a tall, narrow paneled back attached to the trapezoid seat; with storage pieces (called a buffet, armoire, dressoir, or a cupboard) becoming more architectural in the use of columns or pilasters carved with fluting.

The English version, 1500-1660, of the Italian Renaissance was influenced by German and Flemish pattern books, such as the 1577 book Architectura by Johannes de Vries, and the translation into English of a work by Sebastiano Serlio by Robert Peake published in 1611 under the title The First Book of Architecture. The English would soon write their own books, first a treatise by John Shute, entitled Chief Groundes of Architecture (1563), which set down the requirements for the “perfecte architecte;” and then a practical building guide by Sir Henry Wooton, entitled Elements of Architecture (1624). New to the English Renaissance was the use of stairways as a processional route to the high great chamber, upholstered pieces of furniture, with further improvements in board and trestle dining tables, and a new gateleg table which allowed the drop leaf of the table to be raised, thereby enlarging the tabletop surface.

Baroque

Italy remained dominant in ceiling decoration during the Baroque period, 1600-1700, a highly opulent, large scale designing style, involving incredibly intricate details, high contrasting colors, and elements of surprise through the use of light, preference for curves over straight lines, painted and vaulted ceilings, columns, arches, niches, fountains. The materials used were stucco, paint, and fresco, as well as an illusionistic perspective through the use of quadratura, which dramatically extended the vertical dimensions of interior spaces. A new chair with lower backs was designed, with boldly treated curves, detailed carvings on the legs. The storage pieces included the cassone, the credenza, the armoire, the cabinet, and the chest of drawers characterized by intricate moldings, and sometimes flanked by marble columns.

The French Baroque, 1600-1715, found its most creative culmination in the reign of Louis XIV, with France becoming the major source of artistic inspiration to other countries in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The most prominent architect was François Mansart (1598–1666), credited for works “renowned for their high degree of refinement, subtlety, and elegance;” the encouragement of vistas through the use of the enfilade in the arrangement of rooms, vistas from the main suites to the landscaped garden; and vertical perspectives through the dramatic use of light and dark contrasts in the staircase. Jean Barbet’s book Livre d’architecture (1632-41) and Jean Le Pautre’s Cheminées à la moderne (1661) were very influential in the design of highly complex, massive and sculptural chimney pieces with a variety of motifs: swags, scrolls, cartouches, pilasters, entablatures, pediments. The commode, a chest of drawers, was introduced, with some pieces ornamented with ebony veneer using marquetry of tortoiseshell and brass. André-Charles Boulle (1642–1732) was “the most remarkable of all French cabinetmakers.”

The English Baroque was a modification of ideas from France and the Netherlands. The premier British architects were Sir Christopher Wren, Sir John Vanbrugh, William Talman, and Thomas Archer. A spectrum of wall surfaces was used, wood paneling, mirrors, tapestries, textiles, leather, paintings. After the chimney piece, the most decorated feature of a room was the ceiling, deeply compartmentalised; with the most impressive houses using wrought or cast-iron balustrades for their stairways. The primary influence in the making of these stairways was the French smith Jean Tijou and his book, A New Book on Drawings (1693). Increasing importance was attached to the drapery of beds (patterned velvets, silk damask, chintz, and brocade) absorbing most of the costs.

Rococo

France was the setting for the next major epoch in interior and furniture design, which came along with a new emphasis on relaxation and pleasure, with furniture becoming more comfortable, designed for conversation, and chairs more graceful and informal, less stiff than in the Louis XIV period. This was a reflection of both the Enlightened court aristocracy and the nouveaux riche financial bourgeoisie. Rococo was a highly ornate, theatrical, over-the-top style developed as a reaction to the strictness of Baroque. It was a flamboyant, freer, more lighthearted style, with decorative elements that often emulated the look of shells, pebbles, flowers, birds, vines, and leaves.

The foremost French Rococo architect were Robert de Cotte (1656-1735) and Gilles-Marie Oppenhord (1672-1742), as well as the goldsmith and decorator Juste Aurele Meissonier (1695-1750), who published a book, entitled Livre d’ornements. Two types of chair became common, the fauteuil and the bergère, with floral carving, tapestry upholstery, with separate cushion, with emphasis on informality. Many kinds of tables were introduced, some multifunctional, while others for specific functions, such as gaming tables, work tables, serving tables, and coffee tables. Beds were of several types.

In England the style of the period 1715-1760 was “Georgian” rather than Rococo. The Georgian style is a unique combination of Classical and Baroque stylistic features. It is interesting that Lord Shaftesbury, who lived from 1671 to 1713, just before this style emerged in England, one of the most important philosophers of his day, insisted that “a man of breeding and politeness is careful to form his judgments of arts and sciences upon the right models of perfection” (Blakemore, p. 247).

The models of this time emphasized the architectural principles of classicism, the ideas articulated by Andrea Palladio, an expert on Roman architecture. Palladio saw perfection in the classical concept of harmonic proportion based on mathematical ratios. In 1715-1725, Colen Campbell published Vitruvius Britannicus, a survey of English Classical architecture of the 17th and early 18th centuries. Richard Boyle made a grand tour in 1714-15 through France, northern Italy and Rome, where he studied the works of Palladio. James Gibbs also visited Rome and Palladio’s buildings, publishing in 1728 the Book of Architecture and the Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1732). Gibb’s influence is visible in the design of the White House, which employed both Classical as well as the Baroque features of floating pediments, scrolled shoulders and oeil-de-boeuf windows.

However, by the mid-18th century, Rococo became influential in England, with detailing of delicate linear motifs, undulating lines, and natural forms making their way into decorations and buildings. Isaac Ware’s book, A Complete Body of Architecture, published in 1756, emphasized the use of stucco ornamental material (lime, sand, plaster) for grand rooms. There was indeed a lot of variety in styles, combinations of Classical, Baroque, and Rococo motifs. Geometric patterns in floor design were emphasized in Batty Lagley’s The City and Country Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs (1739) and John Carwitham’s Kind of Floor Decorations Represented Both in Plano and Perspective (1739). Casement windows were commonly used while the double-hung window became standard in upper class houses. Windows were often rectangular but some had flattened, arched heads, while some were doubled lancets, representing the Gothic influence during the Rococo phase of the Georgian period. Some windows were more Classical or Palladian, characterized by an arrangement of three openings, with the central window being widest and having a round, arched opening, and the two outer windows flat cornices.

Two cabinet makers, William Ince and John Mayhew, published The Universal System of Household Furniture (1763), a collection of over 300 finely engraved designs in the English rococo style for parlor chairs, claw tables, sideboards, desks, ladies’ secretaries, bookcases, writing tables, candle stands, couches, draperies, girandoles, and more.

The most influential book on furniture was Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754-62), an encyclopedic book offering a broad range of furniture designs with 160 plates covering a wide range of different styles, from a simple, undecorated clothing press to a highly adorned library cabinet with rococo ornaments. Among the wide variety of tables designed during the Chippendale period were the tea table, toilet table, sideboard table for use in the dining room, and a variety of gaming tables for backgammon, cards, and chess. The chest-on-chest (or tallboy) and bachelor chest became typical.

Neoclassic

The Neoclassic style began in France around the 1740s, in reaction to the “excesses, asymmetry, and perceived disorderliness” of Rococo. It came on the heels of major excavations of ancient cities and the emerging study of archeological artifacts and buildings. Jacques Blondel’s four volume work, Architecture françoise (1756), was instrumental in consolidating the French Neoclassic movement. While Renaissance architecture and Baroque architecture already represented partial revivals of the Classical architecture of ancient Rome, the Neoclassical movement was aimed directly against the decorative excesses and ritualistic arrangements of the Late Baroque, and the naturalistic ornament of Rococo, in favor of a purer and more authentic Classical style, adapted to the modern Enlightenment world, characterized by reserve, restraint, and self-command.

Walls were characterized by symmetrical features and rectilinear treatments. Embellishment was reminiscent of the Rococo style, but there was greater discipline and balance. Circular spaces for stairways were frequently used, along with rectilinearity and straight flights of stairs. Various shapes were used for the backs of seat furniture, including medallion, trapezoid, rectangle, and rectangle with a flattened arched cresting. Commodes were very common in many shapes and sizes; a new type was the demilune commode, which was semicircular in shape and featured two drawers in the front and a curved door on each side. Jean-Henri Riesener (1774–1792) was the foremost Neoclassic cabinet-maker in France with a style that was “pure Louis XVI” with its rectilinear side view and harmonious ornamentation.

The English Neoclassic period, 1770-1810, also had a predilection for the linear and symmetrical. One of the most influential members of this movement was the architect and furniture designer Robert Adam (1728-92), author of The Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (1773). Adam actually rejected the Palladian style for what he thought was a more archaeologically accurate Neoclassic style. He emphasized the principle of “movement” that has “the same effect in architecture” as in a landscape, “to produce an agreeable and diversified contour, that groups and contrasts like a picture, and creates variety of light and shade, which gives spirit, beauty and effect to the composition” (Julian Small, The Architecture of Robert Adam). Among his many works are included the ceiling of the Red Drawing Room in Hopetoun House, with its dainty Rococo details composed of foliage, shells, and scrolls in an asymmetrical arrangement, but with some classical motifs. In his furniture designs, Adam also combined some Rococo details but in a more classical direction, as evidenced in his design of chairs with their thin, tapering, fluted legs; and in his lightly scaled and rectangular or semioval tables with their round or square sectioned legs. George Hepplewhite, author of The Cabinet Makers & Upholsterer’s Guide (1788), was enormously influential as far as the construction of Neoclassic furniture was concerned.

Another great furniture designer was Thomas Sheraton, author of Cabinet-Maker’s Dictionary (1803), which included sixty-nine designs for furniture; he strove for lightness through reduction in the width and taller proportions; some characterized his style as feminine in refinement. Sheraton is generally identified with the “late Neoclassic” style, or the “Regency style” of the period 1810-1830, which was more eclectic in absorbing a wider diversity of styles in combination, Greek, Roman, Gothic, Egyptian, Tudor, etc. This eclecticism is apparent in the architect John Nash (1752-1835), who consciously combined discordant styles. The furniture designs of the cabinet maker George Smith, who published A Collection of Designs for Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1808) with 150 colored plates, showed Gothic, Chinese, Egyptian, Roman, and Greek influences.

Some say that Smith copied Thomas Hope’s designs. Hope, author of Household Furniture (1807), was inspired in the designs of his Regency interiors and furniture by his travels in Europe, Greece, Turkey and Egypt. It needs to be said that these were not “borrowings” of architectural styles from the East, but reinterpretations of these styles according to European conceptual principles. Europeans freely borrowed certain non-Western motifs and then integrated them within a European tradition, always searching for new ways while striving for aesthetic perfection. Hope’s influence extended beyond the Regency period, into the Regency Revival of the 1920s and 1930s, and even Art Deco design. Hope aimed to express three qualities in his furniture designs: character, beauty and what he called “appropriate meaning.”

Revival Styles in France and England (1830-1901)

Lucie-Smith thinks that the period between 1800 and 1850 saw more fundamental changes in furniture design than the preceding 200 years. It certainly becomes rather complicated to find clearly demarcated styles due to the combination (and revival) of different styles from Europe’s past and from other cultures, coupled with the persistent creativity and novelties introduced by new generations of gifted designers.

The French Revival was a continuation and further development of tendencies already visible during the Napoleonic Empire period (1805-1815), with its monumentality, the grand scale, and stateliness. The typical furniture pieces of this Empire period were heavy, severe, with sharp corners and little moldings, imposing, with uninterrupted flat surfaces, heavy bases for cabinet pieces, and symmetry. During the reign of Louis Philippe, 1815-30, the Napoleonic style remained paramount through to the Second Empire, 1850-70, with its most successful architect, Charles Gamier, combining the Baroque, Renaissance, and Rococo styles. In both England and France, the impact of the industrial revolution was felt as machine processes began to replace craftsmen, though high-style furniture continued to emphasize high quality skill work. There was a lot of variety in the treatment of chair backs, “upholstered, straight, backward scroll, rounded top, openwork centered with cross bars, arcade revealing Gothic influence with crocketed finials” (Blakemore, p. 383). Lavish display of upholstery was common, and multiple-seat units were produced; the tops of tables were round, oval, octagonal, square, or rectangular; and the legs were carved in the form of colonnettes, chimeras, sphinxes, lions, human figures.

The historical setting of the English Revival Style was the industrial transformation, the material prosperity achieved by the middle classes, and the opening of international markets with the spread of railway lines across the world. The word “eclecticism” is commonly used to describe this Victorian era because more than ever designers combined a variety of past styles adapted to contemporary uses. This was expressed in books, such as Henry Shaw’s Specimens of Ancient Architecture (1836), Robert Bridgens, Furniture with Candelabra and Interior Decoration (1838), which displayed Grecian Gothic, and Elizabethan designs. A. W. N. Pugin (1812-52) was a keen advocate of Gothic revival, publishing the pattern book Gothic Furniture in the Style of the Fifteenth Century, as well as Bruce James Talbert, author of Gothic Forms Applied to Furniture (1867). Belvoir Castle, completed in 1825, was a mixture of Gothic, Baroque, and Rococo, Norman and Classical. The style of chimneys reflected this eclecticism, which came in different combinations; the chimney of the Drawing Room in the Carlton Towers (1873-77) reflected Gothic, Elizabethan, Adam, Georgian Revival, Rococo, and other styles. This variety of styles was reflected as well in furniture pieces.

Art Nouveau, Art Deco, and Modernism

Art Nouveau (1890-1914), Art Deco (1910-1945), and Modernism (1940s-late 20th Century) are difficult to compartmentalize into clear time periods and cultural movements because they evolved from combinations of intersecting artistic currents in different national European cultures with their own flavors and motifs, beyond buildings and furniture, with the latter two movements influencing the design of multiple industrial consumer items, cars and locomotives, radios and vacuum cleaners. Modernism alone includes many different styles, such as the Bauhaus school, Expressionism, Constructivism, Brutalism, Metabolism, and even Postmodernism.

Art Nouveau aimed at modernizing design and escaping the increasingly eclectic and historically oriented Neoclassic and Revivalist styles. It was modern in its rejection of the traditional hierarchy of the arts, the aristocratic elevation of painting, sculpture, and architecture over the craft-based decorative arts. We can say that it was “democratic” in its insistence that art should become part of the everyday life of citizens, not only the “high” arts, but ceramics, metalwork, fashion, middle class furniture and interior design, with a view to enhancing the aesthetic sensibilities of the wider public. But we can say that it was not “democratic” in its emphasis on high quality crafts and its criticism of the repetitive designs of mass-produced industrial furniture and decoration. It certainly remained aristocratic in its commitment to “Aestheticism,” the pursuit of “art for art’s sake,” exaltation of beauty and individual self-expression over the “restrictive conformity” and moralism of Victorian Revivalism. Shapes and lines (smooth curves, graceful bends and dancing lines) were very significant, sometimes combined with bright colors, from burnt oranges and mustard yellows, to olive greens and soft blues. There is no space to list the numerous artists from all over Europe associated with Art Nouveau. I will mention the Belgium architect and furniture designer Victor Horta (1861-1947), and Louis Majorelle (1859-1926) who are said to have contributed the most to Art Nouveau furniture.

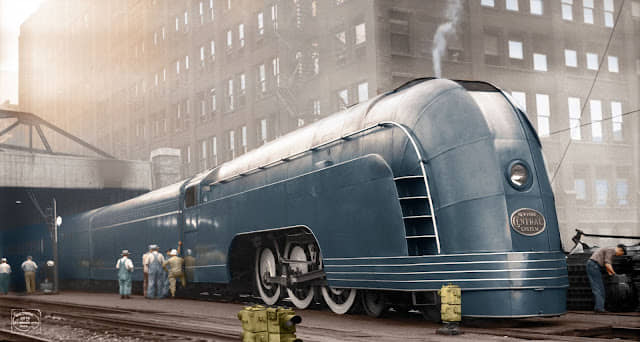

Art Deco, possibly the most talked about movement in history, is a product of the European modern aesthetic imagination, as well as the first truly international style in art, influencing the architecture of buildings around the world. It was a popular style that influenced not only buildings and furniture, but also jewelry, graphic arts, fashion, cars, gas pumps, trains, ocean liners, and everyday personal objects, such as radios and vacuum cleaners. It seems simple to identify with its sleek, streamlined features, vertical lines, zigzagged patterns and rectilinear shapes. But it is a complex movement influenced by divergent artistic currents, including the bold geometric forms of Cubism, the bright colors of Fauvism, Russian Constructivism, Italian Futurism, and Modernism generally.

While Art Deco was influenced by archeological discoveries in Egypt, and the growing globalization of the European mind and ethnographic interest in the Orient and in African art, it was a movement that looked to the future, not to the past. Art Deco’s appearance is overwhelmingly reflective of the invention of industrial machines by Europeans and Americans, their advancements in the use of new materials, such as aluminum, stainless steel, glass and plastic, and their aesthetic imagination to create art out of the aerodynamic principles of motion originated by Western scientists. This futuristic orientation was evident in the Streamline Moderne version of Deco, which took off during the 1930s, featuring curving shapes, smooth surfaces, and long horizontal lines, in the industrial design of both moving objects, such cars, trains, ships, and of everyday consumer items, such as kitchen appliances, telephones, giving these products the impression of sleekness, motion and speed.

But if Art Deco was characterized by clean lines and smooth surfaces, and no decoration on the facades of buildings, it also saw an explosion of colors, bright and contrasting hues, in furniture upholstery, carpets, screens, wallpaper and fabrics. While Art Deco, similarly to Art Nouveau, emphasized the uniqueness and originality of handmade objects, Deco took the incipient anti-aristocratic impulses of Art Nouveau in a more democratic or consumer-oriented direction. Its aim was less to focus on art for art’s sake than to make machine-made objects aesthetically appealing to the increasingly affluent masses of the “roaring 1920s”: lamps, clocks, ashtrays, bicycles, and movies in Deco theatres. However, Art Deco did not promote cheaply made products; it certainly used very expensive materials to decorate the first-class salons of ocean liners, deluxe trains, and the lobbies of skyscrapers, though after the Great Depression the items infused with Deco motifs became less conspicuous consumer items.

There are too many names associated with Art Deco, if only because of the multiple ways it found expression in ornamental crafts, industrial designs, and consumer products. In furniture design some of the main names are the cabinet maker Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1879-1933), a pure Frenchman, Maurice Dufrène (1876-1955), Jean-Michel Frank (1895-1941), and Paul Follot (1877-1941).

We can date the beginnings of modernism with Le Corbusier’s book, L’art décoratif d’aujourd’hui, published in 1925, a polemical treatise against Art Nouveau and Art Deco, and in favor of the idea that furniture, buildings, and objects intended for practical uses should be devoid of any decoration and aesthetic motifs. “Modern decoration has no decoration,” declared Le Corbusier. A house was simply “a machine to live in.”

Writing about the deliberately functional, anonymous, and repetitive buildings of modernism may not be a good way to end an article focused on the unsurpassed aesthetic creativity of Europeans. It should be noted, however, that modernism was the one European movement that not only spread everywhere in the world, but encouraged nonwestern architects to make a contribution to this movement, with its principle that function, not aesthetics, is what matters.

Modernism was a by-product of the inherent nature of mass industrial societies to value anonymous practicality, culturally neutral technological efficiency, and the power of modernity. Its anonymous, impersonal character, is congenial to the belief that the West = Modernization = Globalism. Nevertheless, the best architects of the twentieth century were Western: Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan, Daniel Burnham, Raymond Hood, Cass Gilbert, Hugh Ferriss, Le Corbusier, William Van Alen, John Mead Howells, Renzo Piano, Adrian D. Smith, John Burgee, John C. Portman, William Le Baron Jenney.

We should avoid negative blanket reactions against modernism. It was a realistic expression of an emerging new world of mass industrial society with huge cities necessitating practical high rises for millions of inhabitants without the means to pay rent in high quality architectural buildings. We can’t ignore either the reaction against Modernism in the 1970 and 1980s, starting with the groundbreaking 1966 book, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, by Robert Venturi. This book, and Postmodernism generally, agreed that in our mass societies many buildings must serve a function, be practical and efficient in use of energy and materials; however, it rejected the functional purism of Modernism, and called instead for creative mixtures of historic styles from the past, for buildings to be in tune with their environmental settings and in honor of local history and traditions.

Ricardo Duchesne has also written on the creation of the university. He the author of The Uniqueness of Western Civilization, Faustian Man in a Multicultural Age, Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadians.

Featured: “The Front Parlor,” by Walter Gay; painted in 1909.