It is indeed a high privilege to present this interview with Dr. Mark Stocker, the voraciously productive art historian. Readers of the Postil will know Dr. Stocker from the varied ramblings and amusements that he has been offering in these pages. Therefore, it is great delight to have him speak of his real work, his true métier, which is art. He is being interviewed by Dr. Zbigniew Janowski whom our readers also know well. Dr Stocker is the author of over 230 publications, including 10 books and edited books. His latest one, When Britain Went Decimal: the Coinage of 1971 will be published by the Royal Mint in 2021. His extensive research interests include Victorian public monuments, numismatics and New Zealand art. A Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, Mark did his History of Art degree many years ago at King’s College, Cambridge, but firmly denies being either a spy or even a King’s leftie.

Zbigniew Janowski (ZJ): I would like to begin this conversation by reading to you an incident from Leszek Kolakowski’s “Totalitarianism and the Virtue of the Lie” (published in his My Correct Views on Everything, 2005).

“In 1950, in Leningrad, I visited the Hermitage in the company of a few Polish friends. We had a guide (a deputy director of the museum, as far as I remember) who was obviously a knowledgeable art historian. At a certain moment – no opportunity for ideological teaching must be lost – he told us: ‘We have in our cellars, comrades, a lot of corrupt, degenerate bourgeois paintings. We have never displayed them in the museum but perhaps one day we will show them so that Soviet people can see for themselves how deeply bourgeois art has sunk. Indeed, Comrade Stalin teaches us that we should not embellish history.’ I was in the Hermitage again, with other friends, in 1957, a time of relative ‘thaw,’ and the same man was assigned to guide us. We were led to rooms full of modern French paintings. Our guide told us: ‘Here you see the masterpieces of great French painters – Matisse, Cézanne, Braque, and others.’ And, he added (for no opportunity must be lost), ‘do you know that the bourgeois press accused us of refusing to display these paintings in the Hermitage? This was because at a certain moment some rooms in the museum were being redecorated and were temporarily closed, and a bourgeois journalist happened to be here at that moment and then made this ridiculous accusation. Ha, ha.’”

To someone who lives in the West – unless you happen to be a student of Communism or Russia – what Kolakowski says may sound surreal. But what is going on in the US – the destruction of monuments, removal of paintings and sculptures, suspension of purchases of European art by American museums, purchases of minority art, changing names of buildings and streets – is all too familiar and brings to mind the feeling of déja vu. What is your reaction to Kolakowski’s story; and do you see parallels between it and what is going on today?

Mark Stocker (MS): My reaction is to laugh in order not to cry. The 1950 response is chillingly reminiscent of the notorious Nazi ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition – this is of course one of many resemblances between different forms of totalitarianism. Not for the first time, I feel compelled to ask “What’s the difference?” The convenient change of party line by 1957 is a step in the right direction in at least having such art on display, but the same man is suffering from convenient memory loss.

Before I go on to answer your question, I would like nonetheless to put in a plea for not suppressing the “official art” of that time. In this period, art school training in Eastern European countries continued on precisely the traditional lines, valuing technique and crafting, that you and I both admire. I remember being quite moved by a collection presented to a New Zealand art gallery by the Soviet Institute of Cultural Affairs over 50 years ago. No, I am not a “useful idiot.” I believe that however admirable or repellent the regime, art has a life of its own and should not be lazily written off in a determinist way.

To answer your question, I think there is still a way to go before we reach the parlous and risible state of affairs in the Soviet Union of the 1950s. But we must be vigilant and vigorous in terms of arguing for a genuine diversity in what the public sees.

ZJ: Indeed, Kolakowski’s story may seem laughable. But to me, a former denizen of the “socialist paradise,” where I spent the first 25 years of my life, it is not. This is what “socialist realism” was like. In 2020, in the countries of liberal-democracies, we seem to be “back to the future,” in that what is shown in museums must reflect “approved” and “correct” ideology. Indeed, in a umber of museums in the US (and Europe), the purchase of Western art has been suspended; some museums are selling objects from their collections in order to buy more minority art.

Until relatively recently, museum and art-gallery collections were for the human gaze, for observing. This was the understood purpose of such institutions. This is not so today. Art galleries and museums are now at the forefront of the ideological battle. Several months ago, I wrote a piece “The Power of Beauty and the New Museum Barbarians.” In it I made a point which you also made in an official letter to an art institution – that the function of museums is not “raising social consciousness” but to guard artistic heritage. Do you see what some curators are now doing as a betrayal of their mission?

MS: Any “betrayal” probably happened 20 to 40 years ago. We’re too far down that trajectory to apply this term – younger curators in many cases simply don’t know any better. The prime aim of curators and art historians should be to focus on beauty, aesthetics, style, patronage and iconography. Raising social consciousness can be very worthwhile but, in my view, it comes second to these things.

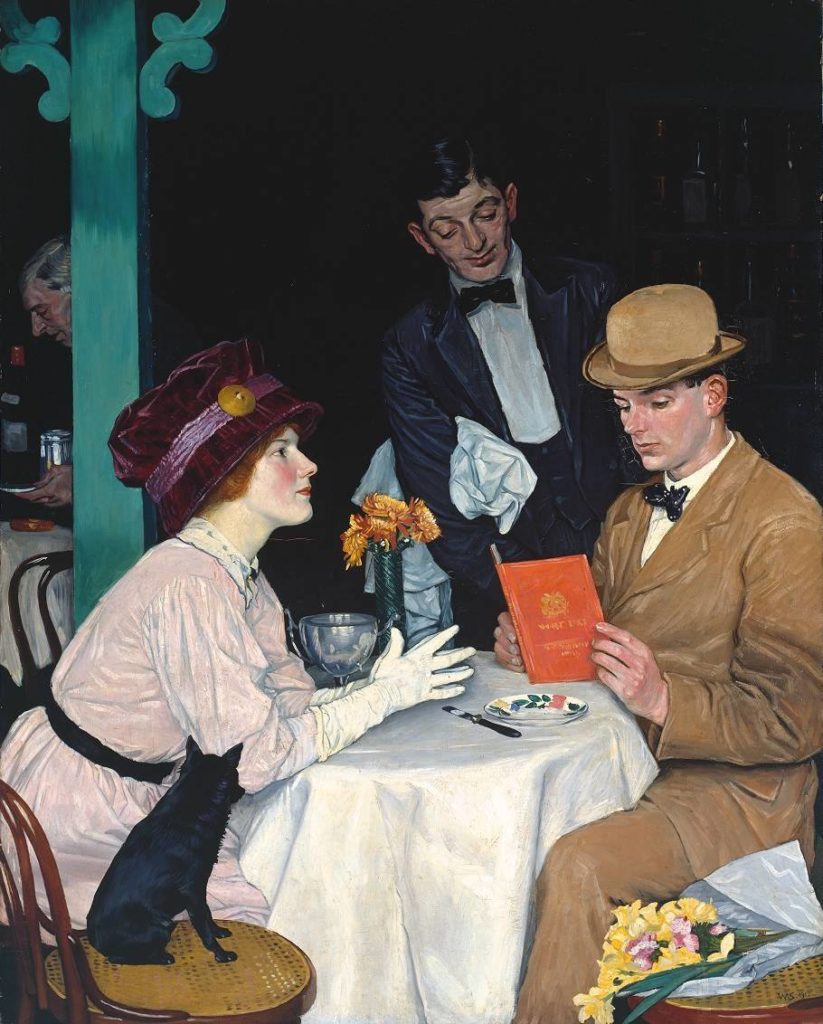

I am very conservative about selling from collections – I wouldn’t want to leave my own art treasures to any state institution, if there was a real danger they would be deaccessioned. If, however, it’s a duplicate print and not in good condition, then it would be silly for the museum in question to be rigid about this. But hocking off anything that’s unfashionable is unforgivable. Why, why, why did the Met see fit to do this with Frank Salisbury’s superb portrait of The Sen Sisters which the artist generously presented to the Museum? He paid a terrible price for being unapologetically academic and a near contemporary of Picasso. An intelligent museum should have both artists represented.

ZJ: That’s the point – unfashionable! Would you apply this term to the Elgin Marbles, Rubens, Watteau, Rembrandt, Veronese, and a host of other greats? The situation in which we found ourselves in the 20th century is singular, I would say. Fashion became a criterion; so that art now is no longer valued for its intrinsic quality, its beauty, but some subjective feeling about “justice.” Of course, there is also the commercial aspect, in that a certain artist is worth investing in, as his work may go up in value. Thus artistic value cannot so easily be separated from profit.

MS: One of the problems that Modernism created was to open a kind of Pandora’s box. Subjectivity and relativism became all the thing, provided you heeded the elite critic’s or curator’s choice, in many ways a contradiction of that. Older, shared criteria of beauty and the concept of art as skill were thrown out the window.

An old friend of mine, now sadly dead, though a big fan of Modernism, said that in architecture, the classical language and Beaux-Arts training guaranteed a base level of consistency and decency, whereas Modernism rejected this. Don’t get me wrong – I’m not dissing modernism – I very much admire Henry Moore and Ben Nicholson, for example, and some of Picasso himself – but we sacrificed a great deal for it and people, even art professionals, are too ignorant to realise this.

ZJ: Do you see this problem as something that creates the danger of confounding artistic quality with the buyer’s inability to separate artistic beauty from monetary value in the art market?

MS: Modernism certainly made it much harder to judge.

ZJ: One can also say that this inability opens the gates for artistic charlatans who prefer to shock the audience with images, rather than enchant them with quiet spiritual elevation?

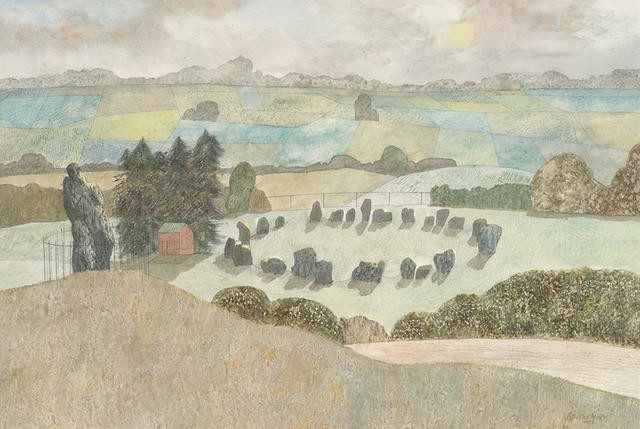

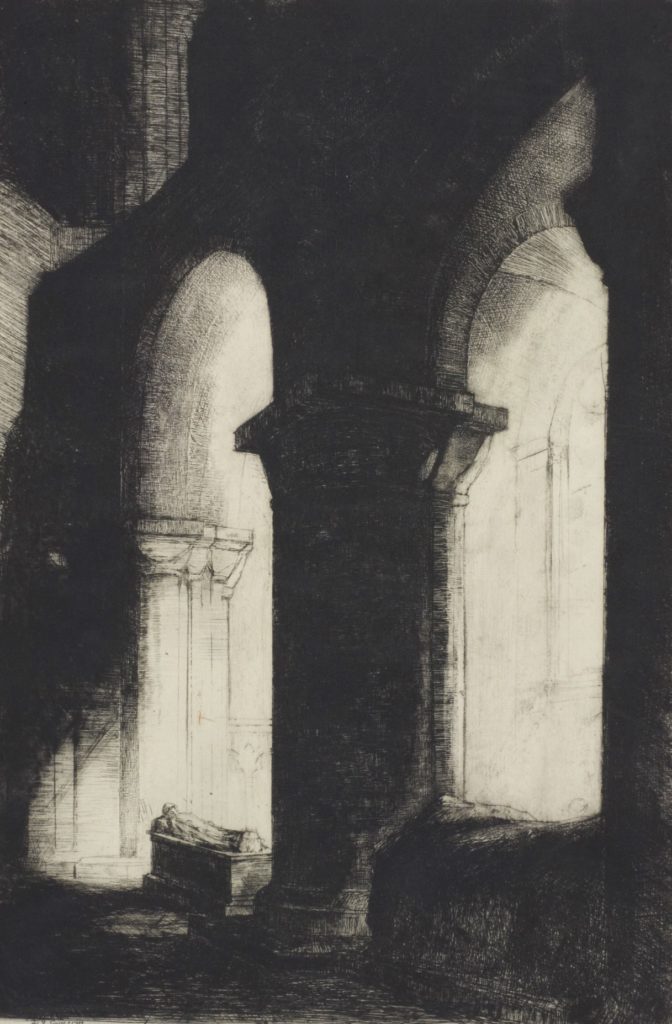

MS: Understated beauty has certainly been a victim of 20th century clamorousness. How many people today can judge the nuances of watercolour washes, as we can see in the work of my good friend Maurice Askew (who died recently aged 98); or, indeed, the deft inking and biting of an etcher’s plate, as in D.Y. Cameron’s sublime Winchester Cathedral?

I don’t totally believe in rejecting the “shock” factor, so long as it is underpinned by skill. Francis Bacon’s Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion is a good case in point; an unforgettable, unavoidable work. But, as Bacon himself found, it was a damn hard act to follow, and his subsequent attempts to shock, certainly after the mid-1950s, just don’t do it for me. Bacon up to the 1960s cannot be fairly described as a charlatan – but I think he came perilously close to being one later in life, using the same painterly tricks and making people who should know better say “Wow!”

What he did become, as many an artist before and after Modernism, was formulaic. The charlatan charge is one that’s easy to level but is in danger of closing the arguments. Certainly the “de-skilling” of art that Modernism encouraged increased the charlatanry component. Damien Hirst – not a skilled painter at all but a brilliant project manager. Josef Beuys – arguably more of a charlatan than a shaman. Marcel Duchamp – he skirted very close to it and stole from others (a time-honoured practice); but he was, I have to concede for all the damage he did, bloody clever.

ZJ: I can’t really abide Duchamp, but let’s move the discussion back to when, earlier, you said, “Raising social consciousness can be very worthwhile but, in my view, it comes second to these things.” Here is my problem: who decides? The curators? Many of them have recently succumbed to social pressure and peddle ideology, sanctioned by state authority – as used to be the case under communism?

Secondly, I’m all for being directed by someone, advised by Dr. Stocker, when I decide what to buy; but social consciousness is a group phenomenon. This raises another question: what are we trying to achieve by raising consciousness? Aesthetic appreciation? Not really. It is a call to social action, an attempt to change society. If so, curators are revolutionaries.

This is not the same as teaching a book. When I say, “Read the Bible, I think you will find it interesting,” my intent is not to make readers into believers. I am leaving the judgment to the reader. It is a process of appreciation.

Richard Sharp, the author of The Engraved Record of the Jacobite Movement, once gave me some excellent advice: “The best way to learn how to distinguish good quality prints from average ones is to look at them; after some time, you will train your eye and you will be able to discern good from average prints.”

MS: Sharp is right. You see what you know, as Gombrich says. As for social consciousness, it can be a dangerous trap and shouldn’t be allowed to obscure the prime concerns of curatorship. It’s a cop-out, but I would leave it at the curator’s discretion as to how much or little a part it should play. But I would be worried if I had a curator colleague who let it loom too large.

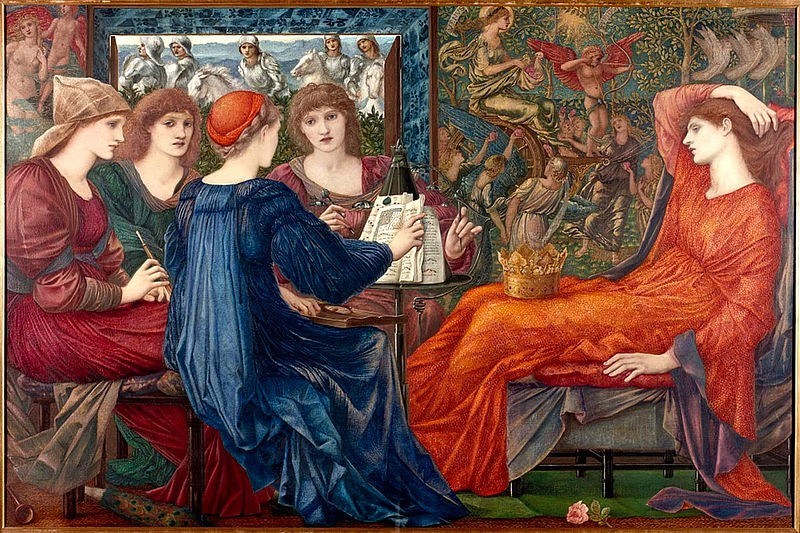

There are aspects of social consciousness which I think could and should be raised and which I find interesting – when for example an artist is outstanding but is the victim of changed fashion or economic decline. The collapse of the printmaking market following the Wall Street Crash is tragic to behold and it would be callous to disregard it in any history, even if the intrinsic qualities of the prints are ultimately more relevant to “pure” art history. Geniuses like F.L. Griggs were ruined. In turn, without becoming a socialist, you can admire someone like William Morris whose conscience was stirred by ugliness, pollution and grinding poverty. His close friend Edward Burne-Jones, though less overtly politicised, wanted to bring beauty into ordinary people’s lives – and his excellent exhibition at Tate Britain a couple of years ago was a powerful vindication of that ideal.

ZJ: One term that is part of the liberal toolbox is “cultural appropriation.” It largely means that the artists has gobbled the best of minority culture and falsely presented it as his own. Recently, Elvis Presley was accused of cultural appropriation (he supposedly “stole” themes and music); Olga Tokarczuk, Polish Nobel Prize Laurate, was accused of cultural appropriation because she wears dreadlocks. In the past it was called fashion, a borrowing. Today it is called “cultural appropriation.”

No culture is entirely self-sufficient; we borrow elements of thought, visual representations from different places, and, by transforming them according to our own perception, create something new, something original. Picasso comes to mind, as does van Gogh, who had a considerable collection of Japanese prints, which inspired him. There is a difference between “appropriation” and “inspiration;” but today inspiration is called “appropriation,” a term frequently and easily interchanged with “theft.”

MS: It is a boring and unhelpful word and concept, and is used all too often by pompous and politically correct academics to close the argument. I would like to remind such people that Picasso said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.” Appropriation wasn’t always seen as a crime. The respected New Zealand Māori artist Selwyn Muru was asked many years ago who he thought the great Māori artists were. “Well, there’s Picasso!” he replied. As for musical appropriation, do Jamaican reggae lovers despise Led Zeppelin for their magnificently appropriated ‘D’yer Ma’ker’? (Get it?). I very much doubt it. They’d see it, surely, as a testament, a tribute, to their culture – attacking it would be a sign of vulnerability.

ZJ: I want to give you two examples: Rembrandt and Stefano della Bella (both 17th-century artists). Apparently, both were fascinated by the 17th-century Polish Sarmatian dresses. Rembrandt even painted his own self-portrait as Polish Nobleman; his student van Vliet made a print, after Rembrandt, of a Pole. Stefano della Bella did several engravings of Poles.

Is this “cultural appropriation?” In Britain, we see a similar fascination with other countries. In the 19th century, Orientalism was widespread. Lawrence of Arabia comes to mind.

MS: As I say, it isn’t a helpful concept. Weren’t the classicists “appropriating” the ancient Greeks? Did the Greeks complain? Get real.

Edward Said has a lot to answer for on that front. He essentialised Orientalism, and though he was a far cleverer and better-read person than me, his effect on countless admirers was to have ultimately trivialised it. Politically correct academics have continued to repeat his litany over the decades, blahblahblah. Full marks therefore to Robert Irwin for intelligently taking him on!

There is much, much more that of course could be said on this front. Sometimes ignorant appropriation can cause understandable offense. I was asked at one stage by Royal Doulton, if in all innocence they could use a Gottfried Lindauer portrait of a Māori chief as a character jug. I told them that this offended on almost every front – the head is tapu (taboo) in traditional Māori culture, and eating and drinking is governed by strict protocols – putting milk in the head jug – OMG – no! They heeded me, thank goodness. But this was an extreme case. Let me give a couple of more New Zealand examples – most people should get my drift.

The white New Zealand artist Gordon Walters received a lot of ill-informed, and I would say pretty offensive criticism in his brilliant use of the fern frond motif that you see in traditional Māori architectural decoration, such as roof beams. But this is by definition “low” ornament and you can’t very well claim he is appropriating your intellectual property.

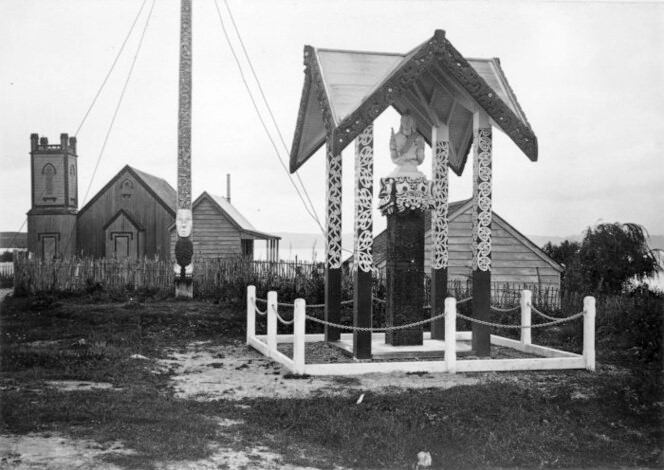

So, inevitably the question of appropriation must be applied on a case by case basis. Oh – it can work in reverse – the Arawa people made the carving of Queen Victoria, that was presented to them, uniquely theirs – by erecting her on a traditionally carved post and protecting her with an elaborate canopy – Queen Victoria became Kuini Wikitoria – get it?! She was even told about it in the last few weeks of her life, and was genuinely moved by the loyalty of her subjects.

ZJ: As you say, the concept is not helpful in explaining the quality of art. But those who use it are not interested in art. They are in the business of fighting Western culture. By saying “appropriation,” they say there is nothing original in Western culture, and that the West is not a civilization that created great wonders, or liberated mankind from poverty and injustice – something the present day “reformers” claim to champion.

Many years ago, Mary Lefkovitz wrote Not Out of Africa – a detailed analysis of the baselessness of the claim that the Greeks had “stolen” their philosophy from Africa – for which she was attacked on all fronts.

What underlies this reasoning is: if we cannot take down all the monuments, remove all paintings from the museums, let’s denigrate them, let’s show the Westerners – the Whites – those who defend Western tradition – that there is nothing special, unique or original in it. On the contrary, it is imperialistic, genocidal, unoriginal, and so on.

MS: Although you’re doing a bit of a reductio ad absurdum, I can’t deny a lot of what you say. I wish it wasn’t like that, but it is all too prevalent. Perhaps it was my luck as an academic that the majority of my colleagues were considerably more intellectually subtle – and in the best sense liberal – than your bleak picture suggests. The better academics put Lefkowitz on their reading lists; and to be fair, Bernal’s Black Athena was rapidly shot down.

ZJ: When you were a student at Cambridge, some 40 years ago, would you ever have thought or suspected that art and art criticism would be gone in the future, and that what you, and others, who had decided to study art, would be under attack?

MS: Perhaps I’m fortunate but my (almost) 30 years teaching at the academy were remarkable for not being attacked. Only once, many years ago, when I did a seminar defending (yet still criticizing) Camille Paglia, which was almost riotously well-received by most students and several staff present but not by a few angry left-wingers, was I reprimanded by my head of school. Call me cowardly, but out of self-preservation and a wish to advance my career, I took a deep breath, put the culture wars aside and settled down into writing a succession of entries for the Grove Dictionary of Art – on the patronage and artistic interests of Louis XV, Louix XVI, Marie-Antoinette and Louis-Philippe respectively. Perhaps this was a subtle form of subversion! So rather than buckle under any criticism, I’ve simply done my own thing, publishing a very large amount of what I hope is useful, factual research, often on no grants whatsoever, and enjoyed doing so in the process.

ZJ: I often wonder what Sir Kenneth Clark would say? What would his fabulous BBC program turned into a book – Civilization – look like in 2020?

MS: Well, they recently attempted to do a “Civilisation revisited” called Civilisations, with Simon Schama, Mary Beard and David Olusoga. It was well received, but got some criticism for focusing too much on class and oppression, and not enough on the core aspects of art that I identified above. Relativism replaced discerning aesthetic judgement and as for Clark’s beautiful language – creating art when talking about it, well, something surely was lost here. A few years ago, I published a blog-post whose sub-text was “Come back Kenneth Clark, all is forgiven!” My admirable Pacific colleague Sean said he enjoyed it and learnt from it – that’s the whole point, isn’t it?

ZJ: Over the last several years, we have witnessed another phenomenon: tearing down and removing monuments. The first was done by hooligan demonstrators, the second by city officials, who often, as happened in Baltimore, removed monuments during the night, when the public was asleep. Many monuments were not just representations of someone others disapprove of, but pieces of art. Do you see any hope for saving public monuments?

MS: Actually, I see some hope from the British Tories (though I often disagree with them elsewhere) in the very latest news. They are planning legislation to take decisions away from councils and make statuary subject to the minister’s edict. So long as the government is sound here, that will make it very much harder to molest public monuments, and cathedral and church monuments in turn. I’ve recently come across a specific instance of this in regard to a taxpayer-funded academic research project on the Napoleonic tombs in St Paul’s Cathedral. The proposal read positively scarily: “Unlike the early- to mid-20thC monuments to Confederate soldiers, the St Paul’s Pantheon is unlikely to be removed in the long term.” You bet it won’t be, now that I alerted the Church Monuments Society and the London Times – I (indirectly) received a hurried reassurance to this effect just days ago. But the very fact that the project hinted otherwise, and got government funding, shows there is no cause for complacency on this front.

ZJ: What about selling them?

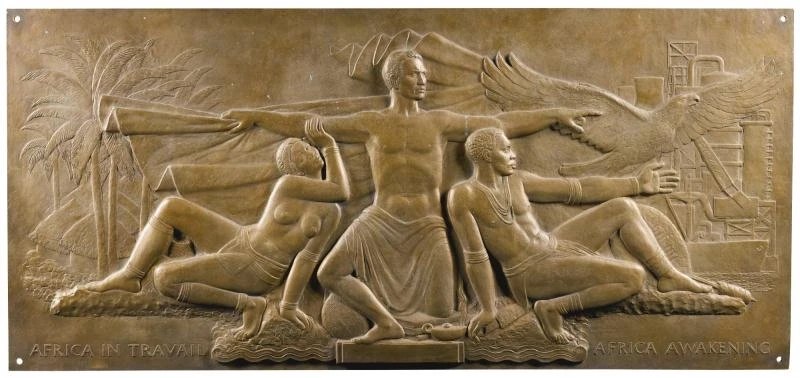

MS: I like your idea of selling monuments but I don’t think there would be a big market for them. With a couple of sculpture-nut friends, we’re currently trying to find a home for a HUGE relief of very fine quality, celebrating Africa but carved by a white British sculptor in the early 1960s and nobody wants to know – it’s all too “sensitive,” you see; well, my response is to say “Bah!” It’s a history lesson in stone, and fascinating for it. Somebody who should have known better described the sculpture as “patronizing.” If you could travel back in time and tell the artist this, he wouldn’t be offended so much as baffled and bewildered. The past is a foreign country – and imposing presentism on it in this way is quite simply bad history (and bad art history).

Art And The Public

ZJ: Recent events – destruction of monuments, changes in the museums’ policies – raise the very serious problem of “art ownership,” not ownership in the ordinary sense, where I own an antique-piece or a house. The question is – who is entitled to a work of someone who has been gone for centuries and whose work was created in a very different world-view. Do we – today – have the singular claim of deciding what the “proper” subject of art must be – or indeed what the artist should have thought and what he should represented in his art?

But today, if someone happens to disapprove of something, we destroy it or remove it.

MS: There’s a big risk of not wanting to look at the monument in its own terms, to neglect the history surrounding it and say our history must dominate – in other words presentism. If it’s a statue in a public place, it belongs to the people but is being held in trust/custody for them, and we disrespect this at our peril.

ZJ: In the early 1980s, the Greek government wanted Lord Elgin’s Parthenon marbles back, claiming they are part of Greek national heritage. This claim is not as strong as it appears to be. Modern Greece is not a continuation of ancient Greece. That cultural continuity had been broken many times, especially during the Ottoman rule. Secondly, the Greek heritage, because of the unique place of ancient Greece as cradle of Western civilization, is as much English and European as it is Greek. Finally, the place that deserves guardianship of ancient relics is that which can preserve best them.

MS: They still do. I could write 5000 words on this and I have. The arguments for and against are quite closely balanced. To me, bleeding heart liberal if you like, the unfair thing about them was that it was not a “level playing field” when Elgin brilliantly and opportunistically exploited the wording of the Ottoman Empire’s permit to remove them – a matter of 20 years or so before the Greek War of Independence. The Greeks had no say about them. Short term, they had everything to be grateful for in Elgin “rescuing” them from what could well have been fatal destruction. But for 150+ years they have been saying “We want them back, please!”

The question of modern Greece not being the same place is one of the strengths of NOT returning them; this must be conceded. But having them in the locality of where the whole great world of Western art – and democracy – started is an emotional one that many people find compelling. A good comparison would be if Paris or Munich owned Boadicea’s chariot!

ZJ: A critic can argue, however, that the best place for it is the original site. But, once again, one can counter-argue that the original site is not necessarily the safest. The prime example is the Roman city of Palmyra, vandalized and partly destroyed by ISIS a few years ago. By contrast, the Pergamon Altar was preserved because it was removed and beautifully preserved in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

MS: Or was till the anti-Satanist nutcases recently struck. In regard to the Parthenon marbles, Enoch Powell said clean up the Athens pollution and then put them back in situ. I got what he meant even if practicality (and emotions) meant that his typical intellectual logic was shouted down.

ZJ: True, the Elgin Marbles, the Pergamon Altar, the Ishtar Gate were taken away; yet, were it not for the passion of those who carried out this “theft,” they might well be entirely destroyed now – their “theft” in turn preserved them. This also tells us that the heritage of civilization belongs to those who can secure its welfare the best.

MS: At the time, the 1810s, I think even the Greeks would have conceded that. What they argue is that they are now a liberal democracy, part of the European Union, which Britain was till so recently, that they have the means, facilities and expertise to house these treasures in a beautiful, accessible way, just metres from where it all began. My feeling is that the return of the Parthenon marbles is about 60% justified – quite narrow.

Where I am totally opposed to the restitution of art objects is when you cannot trust the government that wants them back. Some years ago, there was a genuine, albeit politically incorrect worry that the consequences of returning Benin bronzes to the government of their country of origin would be Lamborghinis and wives’ shopping sprees in Harrods and Aspreys! Any “returning” institution needs to be given a pretty copper-bottomed guarantee that their treasures will be beautifully housed, displayed and loved. If not, they should stay put.

ZJ: My second question is a variant of the previous one. Ever since the French, American and Russian Revolutions, we have to deal with a new concept that implicates art in a way it was created for, in that art is the property of the people. Hence all kinds of claim can be made. It is a people who are true owners, not individuals. The proper place for art is museums; and private collections, even if they legally belong to private citizens, cannot be taken out of the country, sold in other countries, because, the claim goes, it is part of “national heritage.” How strong is such a claim in your opinion?

MS: This is a long and complex one to answer. Obviously if you believe in liberal democracy, you believe in the rule of law and the sanctity of the ownership of property (statue-topplers take note). The last, however, needs to be balanced with caring for the national heritage.

In the absence of protective legislation or the purchase of masterpieces by the government and private donors to keep them in their country of origin or long-term custodianship, the consequences can be disastrous. The New Zealand Māori in the first instance and our culture in the second suffered from the despoiling of ghastly, latter-day grave robbers.

Even when the repatriation is legal, the consequences can be near tragic – Japan exported so many of its glorious colour woodblock prints, the country was effectively despoiled of them and any uninformed international tourists who went there to see them were disappointed.

Modern Art And Architecture

ZJ: I would like to move to modern or 20th-century art. It is the period which is very often criticized. As far as painting is concerned, this era is often appreciated by art critics more than the public. Ordinary people find modern art difficult to understand (especially abstract painting), lacking in immediate aesthetic appeal, sometimes even appalling. Similar criticism can be applied to architecture.

In its simple form, criticism of art and architecture can, in my view, be reduced to three claims: it is “ugly,” i.e., lacking in aesthetic dimension, like in “this building is ugly.”

Second, it is ugly because it has no relationship to tradition, surroundings, regional and national features (this is true of much of modern architecture). Such art and architecture follows abstract geometrical patterns rather than traditions; thus, the ornaments which beautify buildings are absent.

Thirdly, it is ugly or not appealing because the purpose of a painting or a sculpture is not to convey a sense of beauty but to embody a social message, which turns art into a vehicle of ideology. Of course, there can be an overlap, something can be both ugly, rootless and ideological; and so because it is rootless it is often ugly.

Which of these three assertions would you consider to be the greatest problem for modern art? I realize that not all three apply to the same degree to architecture, sculpture and painting.

MS: That’s a big question. I do think your approach to modernism is too broad-brushed. I genuinely think that a lot of it is a lot less elitist than when it first appeared. Look at the crowds of people looking at Rothko. My old house in Christchurch was a charming slightly Lego-like postmodern affair that showed an obvious awareness of Mondrian.

Let me say this about Modernist architecture: when built on a strict budget, housing or officing (new word) the masses, it can be little short of ghastly. That great old architectural reactionary Sir Reginald Blomfield was unfortunately spot on when he called early Modernist buildings packing-cases. However, when it is built on a big budget, sometimes – depending on the sensibility of the architect – Modernism can look genuinely impressive. There’s been a tendency towards a kind of neo-modernism since the end of the century which focusses on lightness, whiteness and airiness – and people really like it.

ZJ: Let me invoke Nikolaus Pevsner, author of several important books on art and architecture. According to him, England’s “contribution to Western art has been stronger in the practical art of building than in the more esoteric arts of painting and sculpture.” And, Pevsner also said, “English political strength” turned out “detrimental to art:” “…The democratic rule by committee and majority. Building today more than ever before is decided by committees. Committees can never be hoped to be the best judges in matters aesthetics. To demand or merely to license a bold building requires a bold man.”

MS: How prophetic – and we’ve had 65 years of committees ever since! He’s proved to be somewhat wrong about English sculpture (Henry Moore anyone? Barbara Hepworth? The excellent Elisabeth Frink?) and I think he still had some way to go in ever warming to Victorian painting, though he did so splendidly to architecture.

ZJ: These words, as you noticed, were written in 1955, and we are as far away from solving the problem as we were then. I just spoke with an architect, who, to my rather dreadful remark – which I made jokingly – as to what we should do with architects who litter our cities with buildings which are admired only by fellow-architects, said: it is the investor who is responsible; we do what investor wants. I find such an answer to be nothing other than a cop-out, an easy excuse that covers architects’ lack of talent; or worse, it’s a total disregard for “the public,” traditional surroundings, or national culture.

MS: As I said earlier, one of the tragedies of the 20th century was when capitalists realized that cheap Modernist architecture was the way to go! So, your friend does have a point. But architects also have themselves to blame – they are arrogant and self-referential. Look at architects like Morris Lapidus, who was brave enough to design for the people – despised by his profession, and in old age he destroyed his drawings and models – tragic.

ZJ: We have three choices, it seems: the committees, the public, or the bold man, who always realizes his own vision, not necessarily shared by the rest (as Pevsner suggested). Personally, I would go for the second, but would add that the committees offer us – the public – a range of, say, ten designs, submitted by architects, and have them displayed in a big public place, and let the people cast a vote. After all, it is the public and future generations who will live with it, not the architect, not the coterie of members of the committee. Which option do you think is the best?

MS: They all have their pros and cons. Going against my liberal instincts, I have a soft spot for the bold man – provided his taste doesn’t totally offend me. The people aren’t always right – they are often very conservative in turn. Sometimes they have to catch up with an artist and realize his or her validity. Henry Moore is a good example, even if a lot of his later corporate work, loved by committees, is boring.

But sometimes time cannot heal an “in your face” ugly work of art – Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc is a prime example, as is “Brutalist” architecture of the 1950s and 1960s – a fair bit of that probably remains in Poland in cheap public housing. My friend Amanda was very upset when I published a letter saying a whole lot of Brutalist flats weren’t worth keeping in Wellington, utterly lacking in the “period charm” of their Art Deco predecessors of 20-30 years earlier!

ZJ: Only yesterday I had a conversation with an architect who used the language of “experimentation” in art, saying that a piece of architecture “was an interesting idea.” My response was that there is no question that Centre Pompidou is “interesting” as an idea; it never occurred to anyone before to show the inside of a building. But it is ugly.

Here I would like to suggest a topic for reflection. The two towers of the World Trade Center in New York were, for decades, seen by the public as a symbol of New York itself, the New World. When the towers collapsed on September 11, the question became – should we rebuild them? But no one entertained this for long. Rebuilding certain architectural objects is not new; it says something about national spirit, attachment to history, tradition. An example is the old city of Warsaw, razed to the ground during WWII. It was rebuilt as exact copy of the city from before 1939.

Most recently we have the example of the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. It was a heart-breaking sight to see it in flames. There was no question that it will be rebuilt as it was, perhaps with small details which will be modern.

The two objects – the Twin Towers and the Notre Dame – are good examples of where the problem lies: -beauty of a building, as opposed to “an interesting idea.” I doubt whether the same French public would ever entertain the idea of rebuilding the Centre Pompidou if anything were to happen to it.

MS: What you’re saying is that there is something humanist that is enshrined in old buildings, that the public love and which we badly miss when they are gone. I can’t argue with that even if some old buildings were or are no great shakes. There are open and shut cases of ugly buildings – often, but not exclusively, Modernist – which nobody mourns if they go. And I don’t think merely being there for 40 years or more can redeem them.

The “Brutalist” flats in Wellington I mentioned earlier, known as the “Gordon Wilson flats” after their architect, had a certain “to-hell-with-you” quality when they were erected, and they haven’t mellowed – they were ugly then and ugly now, which you can’t say for a lot of Victorian architecture. Frankly, I wouldn’t grieve to see them go. Any decision has to be on a case-by-case, empirical basis. Personally, I don’t agree with you about the Beaubourg – when I first saw it, and I was definitely a bit of a fogey – I was impressed by its quirky, funky qualities, and it was obvious that in the piazza in front of it, buskers, jugglers, tourists and Parisians, took to it like a duck to water.

ZJ: Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright and Gaudi. They are giants of 20th-century architecture. The first two were giants of the new 20th-century style; the other two are modern too, but they are steeped in tradition; their knowledge of history of architecture is undeniable. Gaudi’s Sacrada Familia Cathedral in Barcelona is not a medieval cathedral, but only someone unfamiliar with history – Gothic architecture – could confuse it with something else. Frank Lloyd Wright’s houses, his use of stained glass, wood, triangular roofs, bricks, in short, traditional material, make us feel “at home.” None of this is part of van der Rohe and Le Corbusier’s vision. It is pure geometry of new material, which makes us feel alienated from the environment and history. Such “creativity” is responsible for much of the problem with modern art.

What is your take on it?

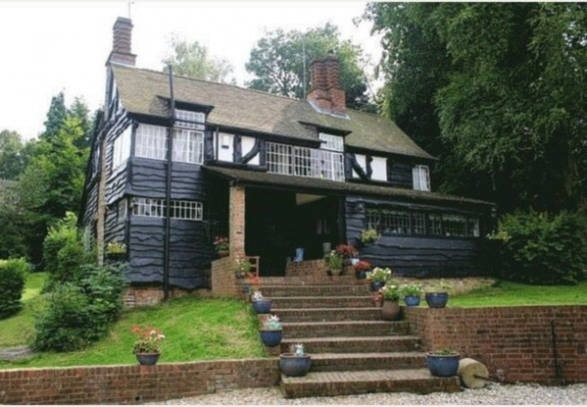

MS: A lot of Le Corbusier’s theories were cranky and it grieves me that he had so much influence on generations of architecture students – to be terribly provocative I tell them they should have looked at Corb’s contemporary, Ernest Trobridge, architect of startling “ye olde” suburban houses in Greater London, instead. Le Corbusier’s architecture is, dare I say, hit and miss – the much-lauded Unité d’Habitation was a flop; I haven’ been to Ronchamp but I’m pretty certain I would admire it. Mies van der Rohe had a genuine sensibility towards proportions and materials – his actual buildings are rather great – the problem is that lacking that sensibility, lacking that big budget, being a second-rate Corb or Mies – is a recipe for aesthetic, social and political disaster.

ZJ: Let me approach the idea of conservatism in art. It is a category external to art. If it makes sense to talk about conservatism in art, it concerns national attitude, national characteristics rather than artistic qualities. Pevsner wrote an interesting book, The Englishness of English Art, in which he pointed to certain creative stubbornness, so to speak, of the English.

Christopher Wren, for example, had to redo the plan for St. Paul’s cathedral, because the clergy refused to accept such “un-English a shape.” Wren also suggested that completing Westminster Abbey in Gothic style was appropriate because “to deviate from the old Form, would be to run into disagreeable Mixture, which no Person of good Taste could relish.” (A point that is relevant in rebuilding the Notre Dame in Paris). Pevsner’s book abounds in examples of this kind. What we deal with is “Englishness,” if I may say so, or English conservative attitude in general.

This was all a long time ago; things changed! In the 1990s Prince Charles left the confines of his regal realm and made a name for himself by his criticism of English architecture. He even wrote a book, A Vision of Britain. Another critic of English architecture is Sir Roger Scruton – one of its most vocal critics, in fact. Can you explain this criticism?

MS: The architectural consequences of Prince Charles is an interesting topic and would really repay research – a book in itself. There are not a few examples of how late 20th- and early 21st-century architecture ‘kept in keeping’ with pre-existing structures – a really good example of this is Downing College, Cambridge, which is pretty awesome and which Scruton doubtless admired. And the model village of Poundbury where pundits’ opinions are divided but whose residents appear to love it.

Prince Charles himself influenced the admirable addition to the National Gallery – his critique of the original plans is where it all started. So, this kind of architecture happens – not as often as I would like because, I’m afraid, of the mania for change, cost effectiveness and architects’ egos – not least their over reverence for 20th-century heroes. Where a less admirable form of traditionalism continues to thrive is in the mania for period features in British domestic housing, especially neo-Georgian.

I generalize, but a lot of it is awful, tacky and pretentious. Cambourne, outside Cambridge, falls into this trap. It’s bad, but I laugh at it and don’t feel appalled by it – I can see it worming its way into my affections if I lived there myself. Indeed, I have a feeling that maybe in 50 years’ time, if it lasts that long, it will have accrued a period charm, as the much-mocked mock-Tudor with its painted “beams” and gables of the inter-war years has done.

ZJ: George Orwell, in his essay, “England Your England,” attempted to come to terms with Englishness, the English national character. The essay covers a lot of ground, but one thing that struck me was his claim that the English have no aesthetic taste; and, second, that England does not have great art, great painters. If one compares England with Italy, that is certainly true; but if we take Orwell’s claim at face value, every nation would lose to the Italians. Do you agree with Orwell?

MS: It’s a complicated question but he’s being unfair. The pioneering modernist critic Roger Fry said something on the lines of “the fact that our school may be a second division one does not prevent it from being intensely interesting.” But the ginormous elephant in the room when you make this generalization is the phenomenal, the beautiful, the remarkable English and to a lesser extent Scottish country house – and its garden. British art historians should be shouting from the rooftops about how its landscape architects made the paintings of Claude Lorrain (some of the most gorgeous in art history) three-dimensional reality. It worked better in the cooler, damper British climate than it would have ever done in Claude’s Roman Campagna.

And another major point: a lot of British painting from about 1750 is remarkable and too many critics remain obtusely patronizing about it. I love artists like Burne-Jones (as you’ve gathered), Leighton, and much admire Watts. And in the 20th century, we have Henry Moore, Stanley Spencer, Lucian Freud – and those godawful YBAs, yet who have a huge place in the world of contemporary art. I don’t think it’s profitable comparing Britain to France or Italy – and I think it’s stupid, as the Courtauld Institute did for far too long – to ignore what’s on your doorstep and only bother to look at France and Italy. Many people are snobs like that about cookery – oh they LOVE Italian food. Well, all I can say is that dining out in Rome in 2003, despite using the normally reliable Lonely Planet, was a terrible disappointment and the best Italian meal I had was in Los Angeles, but I digress.

ZJ: You mentioned English art around 1750. The painter of this period that comes to mind is Hogarth. Nikolaus Pevsner, praises Hogarth, who in his The Analysis of Beauty (published in 1753) speaks of “the line of Beauty.” Or, in Pevsner’s words, “a shallow, elegant, undulating double curve. Now the fondness for these double curves is actually, although Hogarth did not know that, a profound English tradition… one that runs from the style of 1300 to Blake and beyond. But it is also an international principle of the Late Baroque and Rococo, and it will be found without any effort in individual figures and whole compositions of Watteau in France, of Tiepolo in Venice, of Ignaz Günter… Hogarth’s Baroque modelling and brushwork and international quality created something in England that had not before existed within English possibilities, in the case of serpentine or zigzag compositions and attitudes, an English quality in Hogarth and an international quality of Hogarth’s age worked hand in hand.”

MS: Firstly, let me say how I deeply admire Pevsner. Initially a card-carrying Modernist on his arrival from Nazi persecution (and the poor man’s biography reveals how seriously – almost like Chamberlain – he underestimated their true evil), he got increasingly hooked on his country of adoption and his attitude to Victorian art and, particularly architecture, intelligently mellowed. I am dubious, however, about this “line” of generalization.

As Pevsner himself realizes, it wasn’t peculiar or particular to the English. And there are strongly linear artists who don’t necessarily go to town with the undulating double curve – Flaxman and Gill for example. If you’re looking for English characteristics, I’d say that the bleak, almost drab palette that is so long dominant in landscape painting – Pre-Raphaelites aside – would be an important one – it explains why watercolour is so strong and we see it in Spencer, Freud and the wonderful L.S. Lowry.

All this relates to Britain’s long, bleak autumns to springs and is almost hard-wired in the English – Scottish even more (look at Joan Eardley). The art historian John Onians – author of Neuroarthistory and a good friend – would certainly agree. By the way, note how many artists I mention are modern ones – I am not some fogey who believed that all was good in art predates 1837 or 1914.

ZJ: Point taken! Sometimes I worry about you being a little too trendy! Seriously, there are other names, Richard Wilson, a great Welsh/English painter, who even wrote about the superiority of English art, and, of course, Turner. I may be mistaken, but it is unlikely that an art historian writing the history of modern painting can bypass these three painters. Perhaps Fry’s criticism in his Reflections on British Painting, from which, I believe, the sentence you quoted comes from, does not do justice to English art?

MS: No. I’m quite a big admirer of Fry, for all my misgivings about Modernism. I can even understand his reaction against bourgeois Victorian conservatism and complacency, though art history has shown his denunciation of Alma-Tadema to be terribly wrong – Alma-Tad was a far better artist than almost all of Fry’s Bloomsbury cronies, as the late Quentin Bell, son of crony-in-chief Clive Bell, generously conceded to me. Fry was certainly beating the Modernist drum, which he understandably felt was all the more necessary in the context of British artistic conservatism. In the process, he gravely underrated Edwardian art, some of which looks superb over a century on, and overrated his Bloomsbury “luvvies.” But critics can, do and even should make mistakes. Fry’s liberalism in the best sense was shown in his admission that British art was “intensely interesting.” Roger, Roger!

Artists And Art Historians

ZJ: Much of how we look at art is influenced by art criticism – that is, what we read. Many ingenious insights, which we could not come up with, do come from reading books by experts. I want to throw at you a few random names of art historians: Nikolaus Pevsner, Richard Wollheim, Sir Banister Fletcher whose History of Architecture, even today, has no rival, Sir Kenneth Clark, Erwin Panofsky, and Ernst Gombrich. I skipped many names of outstanding people who made contributions to more narrow fields, or who wrote about individual artists or epochs. How do you like my list? Would you like to add a few names?

MS: They are the greats, though I always found Wollheim unintelligible and overrated – and he was more of a philosopher of art than an art historian. The art historians I would add are H.W. Janson (a Russian German in origin), Robert Rosenblum (the two authored a magisterial history of 19th-century art in the mid-1980s). Then there’s Hugh Honour – a great writer and scholar; and from a slightly younger generation, I have affection and respect for Frances Spalding who is still alive and kicking. Fiona McCarthy, with her biographies of Morris, Burne-Jones and Eric Gill, is damn good too! She died very recently.

An outstanding populist who never got the national honour he deserved is Edward Lucie-Smith. Though he was a critic more than he was an art historian, Robert Hughes was one of my heroes too – though personally a nasty piece of work. One of the most interesting and original art historians is John Onians, author of Neuroarthistory, who looks at the impact of the mind, childhood and environment on art history in pellucid prose and with convincing reasoning. John would love what I say about Claude Lorrain and country house gardens; he was also the genius behind the World Atlas of Art. By the way, Neuroarthistory was generally panned by the academic left, so it must be good!

ZJ: Let me return to Sir Kenneth Clark, whose biography by James Stourton, Kenneth Clark: Life, Art and Civilization, appeared in 2016, and which makes Sir Kenneth a real 20th-century art history hero.

Neil McGregor, formerly the director of the National Gallery and the British Museum, said about Clark: “[he] was the most brilliant cultural populist of the 20th century… Nobody can talk about pictures on the radio or on the television without knowing that Clark did it first and Clark did it better.”

Would you agree that “to come after Clark” is an unenviable situation for today’s art historians? Not being an art historian, each time I read him, I envy him – this man spent his entire life moving through a world that looked more like an enchanted garden, so different from the lives of ordinary people who live in a world of aesthetic poverty which then prevents them from escaping their social and economic realities.

MS: I couldn’t agree more. Clark is a wonderful man – that comes over in my blog. He was my hero when I was a teenager. He was also a war hero, bringing piano music free to all visitors to the National Gallery when all the paintings had to be removed for safekeeping. He inspired me – and I bet a fair few other people aged 60+ who won’t admit it – to become an art historian. “What do you want to be?” I was asked at my Cambridge interview. “Another Kenneth Clark!” was my modest reply. I didn’t quite make it but I certainly tried. I did so in the wide range of themes I have researched and published – one of the aims was to flummox and irritate other academics who remained stuck in the same groove.

Back to Clark – anyone who could write with authority on Rembrandt, Leonardo, the landscape, the nude and don’t let’s overlook the Gothic Revival, his first, underrated book, has got to be a good thing. The other thing that I admire in him is his beautiful and accessible writing. In everything I write, I ask, “Would Kenneth Clark approve of this?” I hope so: we ignore him at our peril, and the Stourton biography along with the Tate exhibition are both timely reminders of this.

ZJ: John Ruskin said that beauty was everyone’s birthright. This brings me to the question that should make people like you, art historians, very concerned. Art education is probably the most neglected discipline in popular education, in every country. For years I made the reading of a few pages from Clark’s The Nude part of my “Introduction to Philosophy” course, where I sent my students to a museum to write a very specific paper connected with what we had read.

This assignment was probably the most fruitful educational tool I possessed. Student reactions were comparable only to the reaction they had when we read Plato, Nietzsche or Dostoevsky.

You write a regular blog, something that has very limited readership. I sent your piece on Dürer to several of my former students. The reaction to it was probably more than you would expect. Given how people, particularly younger people, react to art, why is art history so marginalized in Western education? Can anything be done about this lack? Getting students on a mandatory trip to a local museum so that they can awaken to art?

MS: It’s a big problem. I wish my blogs had a bigger readership but unfortunately my attempts to publish them on a wider front were not supported by my former museum – partly issues of copyright unfortunately complicated matters. The paradox is that never have more people been going to museums, before 2020, and wanting to see the latest exhibitions; but never in the past 30 years have fewer people formally enrolled to study art at university – and it was even proposed to discontinue the British History of Art A-level. I have several answers to this: the punitive fee regime at university, with careers advisers and family members saying “What’s the relevance of art history?” And the corresponding incentive to study STEM subjects.

And here’s another answer: art history is an overwhelmingly female subject in terms of its students. This is for two or three reasons: firstly, I think men are usually slower in responding to aesthetic matters than women; and secondly, at the risk of being controversial, art historians are ultimately the “servants” of art (or should be); women, in their traditionally supporting roles, adapt to this more easily than hunting, gathering, stomping, blundering men. With the ever-greater gender equalities of the past 30-40 years, which I generally welcome, women have become more masculinized in the choice of what they study. Art history has been the unfortunate victim of this.

ZJ: In the last 30 years or so, leftist art critics – mainly academics – turned art into an ideological instrument. Enough to glance at The New York Times art section, which peddles ideology under the mask of art. By contrast, the WSJ’s art section is still traditional; informative; and reading it one gets the impression that not much has changed since the 1970s or the 1980s. After reading pieces on art in the WSJ, it makes you want to visit a museum.

A long time ago, Roger Kimball of The New Criterion wrote an important book which he titled, The Rape of the Masters. Kimball, who is not a scholar but an editor, a very able art critic and a true art lover, did a great service to the American public by pointing out what is wrong with what passes for art criticism today.

Let me quote what he said in an interview: “For what we see in the academic art historians I discuss – it is something you see in literary studies, too – is an effort to discount, to deny the essential reality of things in order to enlist them in an ideological war. A family portrait of four young girls is no longer a family portrait of four young girls but a florid allegory of sexual conflict and gender panic. And so on. If one had to sum up the essential purpose and direction of the new academic art historians, one might say that, notwithstanding the variety of their political commitments, they are all engaged in an attack on the idea of the intrinsic. They start from the contrary of Butler’s proposition: nothing is what it is, it is always something else – and, they might add, something worse than it seems.” Do you agree with Kimball?

MS: In a word, yes. Too many of the new academic art historians are a bit, let’s say, messed up in the head. They want to politicise bloody everything. Too many of them are scared of just looking. I wish there were more Kimballs in the university but their younger versions probably, sadly, realise that after their BA, certainly their MA, it is not the place for them.

Talking of the painting of girls, the funniest instance of this – oh how I wish I had kept it – was a po-faced feminist discussion of “agency” in Sofonisba Anguissola’s painting, The Chess Game, which referred to the three main participants as “women.” Sorry, but apart from the wary looking maid, all three, even the eldest (certainly at the time) are girls!

And while I’m at it, Sofonisba’s painting is somewhat provincial, even somewhat inept – she was 20 when she painted it and she made her heads look a bit like puddings – perhaps in a Ruskinian way I love the painting for its very awkwardness. I’m slightly digressing, but the feminist response was a classic case of somebody who reads too much and doesn’t look nearly enough.

As for art criticism, perhaps I’m a bit of an exception but I’ve written probably 100 reviews, including a fair few in the Burlington Magazine – there’s still scope for the art historian to be a critic though there is a strange lack of competition which enabled me to go to the top, so to speak, here.

Always, always, I try to summarise what the exhibition is about, what its aims are, how well it succeeds, and of course I try to appraise the quality of the works too and their impact on me. Sometimes I’m converted by an exhibition – I found myself admiring the British 20th-century painter William Coldstream.

More rarely I’m repelled, as with the Australian painter Rupert Bunny who deserved to be shot! At times I am necessarily political – as when I reviewed 20th-century Jewish art and more recently Pre-Raphaelite women – but it’s essential to keep a sense of balance and not neglect these other, core aspects. I hope to keep up this criticism for a fair while yet – pandemics permitting – as there’s so much great – and indeed “intensely interesting” art out there in the world – to experience and share.

Although he could be maddeningly contradictory, John Ruskin powerfully and beautifully stated how the primary aim of the artist should be art and nature, not changing the world: “Does a man die at your feet – your business is not to help him but to note the colour of his lips.”

ZJ: John Ruskin, I love you! Thank you, Dr. Stocker, for this delightful conversation!

Zbigniew Janowski is the author of Cartesian Theodicy: Descartes’ Quest for Certitude, Index Augustino-Cartésien, Agamemnon’s Tomb: Polish Oresteia (with Catherine O’Neil), How To Read Descartes’ Meditations. He also is the editor of Leszek Kolakowski’s My Correct Views on Everything, The Two Eyes of Spinoza and Other Essays on Philosophers, John Stuart Mill: On Democracy, Freedom and Government & Other Selected Writings. His new book, Homo Americanus: Rise of Democratic Totalitarianism in America, will be published in 2021.

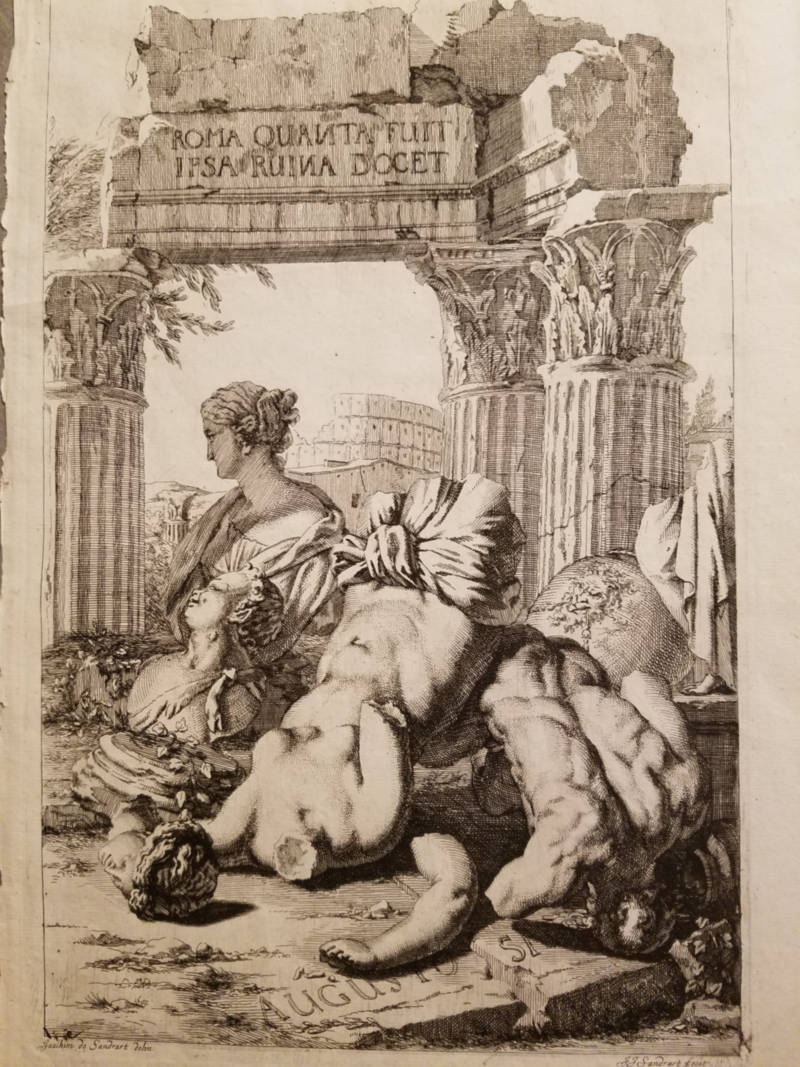

The image shows,”Ruins in Rome – Colosseum, Italy,” by Joachim von Sandrart. Print from 1676.