In November 2020, I helped to organise the Burlington Magazine/ Public Statues and Sculpture Association (PSSA) Webinar on “Toppling Statues.” It was a massive success, with speakers of a multiplicity of political views, representing multiple nationalities and ethnicities, multiple professions from curators to politicians to artists, with anything from Confederate monuments to Rhodes and Colston in Britain to the contemporary Philippines covered in the papers. I am publishing my own paper here and am most grateful to Nirmal Dass and the Postil Magazine for making this possible.

1. The Rule Of Law

Kudos to Sir Keir Starmer, the British Labour Party’s best leader for 25 years, for saying that Black Lives Matter protestors were “completely wrong” to pull down Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol, and if they advocated this, due process should have been followed. I was forcibly reminded of W.B. Yeats’s famous quotation: “Things fall apart. The centre cannot hold… The best lack all conviction, while the worst are filled with passionate intensity.” These were the parting words of my teenage hero Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation, reflecting on its fragility.

Had I been present at the scene, I too would have remonstrated with the protesters, demanding: “Don’t you know your Locke? ‘Where there is no law, there is tyranny.’” I rest my case, even if the likely rejoinder would be a word half-rhyming with Locke. Another important Lockean precept is the sanctity of public and private property in civil society. Colston was not the crowd’s to wrench off its base and toss into the water. “The law of nature hath obliged all human beings not to harm the life, liberty, health, limb or goods of another,” here the people of Bristol and their statue.

2. Have We Got Colston Wrong?

According to an eminent British historian who must remain anonymous, as opinions are so charged and friendships can be lost – yes, we have. They say this:

“Colston is less culpable than his public reputation has made out. Commentators on both sides describe him on the news as a ‘seventeenth-century slave trader’ pure and simple. He was not: he never ran a slave trading business himself and never made major investments into the trade or drew a steady income – even a minor one – from it. Instead, he made a fortune from trading in other commodities, though twice in his life he became a lesser shareholder in slave-trading voyages launched by others. This was – for whatever reason – not an attractive experience for him because he did not continue it. Instead he became the greatest philanthropist in Bristol’s history, the merchant who did most to help his fellow humans. In particular he ploughed back his huge fortune into three enterprises. One was a school where poor children could receive a free education good enough to enable them to rise in society. Another was a hospital, where those who could not afford medical fees would be treated for no payment. The third was a set of almshouses where elderly poor people were given comfortable retirement homes, each with their own flat. All three survive to the present day. I presume that the school was initially just for boys, but it has long taken girls as well, and all three institutions have lately benefited people from all ethnic groups. The late Victorians – themselves much concerned with finding ways of attaining better social justice – gave him a statue in gratitude for them. I myself think that his contribution to human misery, by those ill-chosen investments, is balanced by his efforts to relieve it in other ways.”

So, even an offending statue demonstrably has a far more complex sub-text once we’ve done our homework. Don’t let your opinions gallop ahead of your knowledge. Be a curious and respectful “pastist,” not a judgemental “presentist” – and remember that was then, this is now. I’ll return to this shortly.

3. Do We Ignorantly Bad-Mouth The Victorians? Are We Willfully Ignorant About Statuemania?

Yes and yes. Remember that not just Rembrandt or Andy Warhol but public statuary is art too, art which excels both in quantity and often quality. Before modernism did so much to de-skill art, if you had the standard training through a sculptor’s studio, art school or a large firm like Farmer & Brindley, your work attained a remarkably proficient technical level. Your attitude to imperialism was immaterial. Harry Bates, a working class, arts and crafts trained sculptor, could make a number of rather fine imperialist monuments.

What mattered was whether you could literally hack it. Very few of the myriad Victorian and Edwardian public monuments could be called inept. What has this got to do with toppling statues? Lots. Scratch a toppler and you’ll find they are with few exceptions ignorant of, or hostile to, Victorian art, whatever the quality. Professor David Olusoga has many interesting things to say about the politics of imperialist statuary but reveals disappointingly little art historical knowledge of, still less aesthetic responsiveness to, the works in question. Remember we’re dealing with art here, not disembodied political texts.

Talking of great Victorian art, earlier this year, I pointedly refused to sign an open letter organised by Australian academics, curators and cultural commentators, demanding the relocation of Captain James Cook’s memorial in Hyde Park, Sydney to a museum. Perusing the signatories, almost without exception, they were modernists or contemporary buffs; the number who knew anything about Cook’s sculptor, Thomas Woolner, and Victorian statuary was perhaps two or three, and they probably cared even less.

4. Beware Of Presentism!

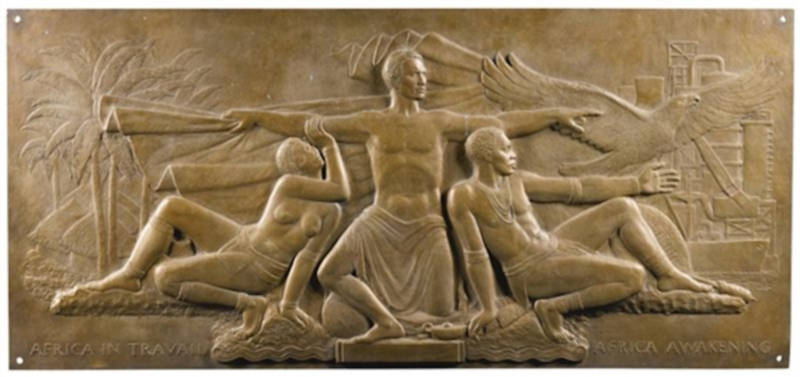

Historically, topplers are deeply into presentism, which is worse than the Whiggery from which it derives. Presentism involves the wholesale application of present-day values, e.g., deploring slavery and racism, to a very different and often resistant past – a foreign country. Imagine if we could travel back in time in the Tardis just 60 years to Gilbert Ledward and his immense – and rather beautiful – Africa Awakening relief for Barclay’s Bank and confront him with a criticism made by a South African friend who should have known better, that it was “patronising.” Ledward would not have been offended, so much as completely baffled and bewildered. We have a nerve to assume we know far better than our equivalents in 1960 or 1860. What will they be saying about us in 2060? The Ledward relief badly needs a new home, but sadly is suffering for its – and his – whiteness.

5. How About A New Empire/Colonial Museum?

A possible new home for relevant statuary could be a UK Empire Museum, a museum of Imperialism if you like. Formerly there was one in Bristol (the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum), but the director’s conduct 10 years ago led to his dismissal and the subsequent liquidation of the museum; that’s another story. I was saddened at the time that they threw out the baby with the bathwater.

William Dalrymple is a prominent advocate of such a museum and I agree with him in principle. My main reservation about both Dalrymple and the prevalent political climate is that if established today, the museum would almost certainly be instantly dominated by decolonising “woke” forces, the Edward Saids of this world rather than the Robert Irwins (or Mark Stockers!). Politics – and Britain’s dire economy – conspire to put such a putative museum on hold, but let’s not lose sight of it. The museum could indeed serve as some kind of repository for victims of statue toppling or shifting.

6. Problems With Museums

Should offending monuments go to museums, as sometimes relative moderates in this debate argue? To contradict my previous point, mostly the answer is, No. How come?

Firstly, the basics – museums worldwide are critically short of storage space and offering them a 3-metre-high statue plus pedestal would exasperate any reasonable collection manager.

Secondly, Colston aside, and even Colston before June 2020, Robert Musil’s famous dictum that there is “nothing in the world quite as invisible as a public monument” held good and perhaps should still do so. It’s not as if a monument’s offensiveness will suddenly be dispelled by its more prominent location and visibility within a museum. The arguments against it won’t miraculously stop – or still more miraculously become more intelligent.

Thirdly, having a Victorian worthy or three in your atrium would almost certainly clash aesthetically with any desired installation of art after c. 1920.

Fourthly, which explains why any proposed relocation of Cook to a museum is crass, how can you possibly do justice to the modelling, the aspect, the halation, the everything really, of a colossal four-metre-high statue on a seven metre columnar base? It would dwarf its new setting, whereas its original location, carefully envisaged by Woolner, is ironically too commandingly successful and dramatic. Cook pays the price in today’s fraught political climate.

Yet a museum just might be a suitable location for a work like Francis Williamson’s statue of Sir George Grey in Auckland. Despite its te reo Maori pedestal inscription translating as “The Future will be grateful for thy universal goodness,” it wasn’t. Grey was decapitated by activists in 1987, while in recent months his replacement head, together with fingers, have been vandalised and his body daubed with paint, in obviously crude copycat actions. Marble is particularly vulnerable, Grey with his fairly recent head still more so, and in the absence of alternative measures a museum could provide an appropriate refuge when out there in Albert Park he’s too much of a risk to society.

7. Copycat Activism

I take a dim view of copycat attacks or calls to defund the police. Just as statuary needs to be appraised on a case-by-case basis, so do the historical records of respective nation states. New Zealand’s colonial past rendered deep injustices to Māori, but these should not be equated with the US’s brutal past. I said this in response to the New Zealand historian Professor Tony Ballantyne when he advocated removal to museums of figures “who propelled colonialism and whose values and actions are now fundamentally at odds with those of our contemporary communities.” I demanded to know “which statues does he mean?” and Tony didn’t answer me. The great white Empress Queen Victoria obviously upheld the Empire but was not racist, and her carving at Ohinemutu was honoured and indeed appropriated by the Ngāti Whakaue sub-tribe, placed on a splendid post and sheltered by a canopy. In Canterbury province, J.R. Godley established a colony which deliberately sought to avoid conflict with Maori and is immortalised in another outstanding statue by Woolner.

Sir George Grey’s role is highly equivocal, reviled in his lifetime by some Maori, eulogised by others; working closely with his friend Te Rangikaheke, he recorded Maori legends, traditions and customs, doing much more here than most academics today. The list goes on, and I concluded: “We should think twice before we violate our legally protected heritage.” Famous last words – but heated discussion has definitely died down locally.

8. Not Everyone Has It In For Statues

The art critic and cultural commentator Alexander Adams has noted the merciful immunity from iconoclasm in the European continent, which views woke excesses with intelligent scepticism, and the perceived heritage value of its historical monuments prevails over politics. President Emmanuel Macron has explicitly stated that France won’t indulge in tearing-down operations, while Ian Morley’s paper has just explored the refreshingly different attitude in the Philippines. Perhaps this is yet another unfortunate instance where the exceptionalist British world, as seen in Brexit, sets itself apart and tears itself apart.

An irony of the peaceful BLM demonstration in Wellington was the crowd gathering under the watchful eye of Thomas Brock’s parliamentary statue of R.J. Seddon, New Zealand premier from 1893 to 1906. While his relations with Maori were benign, Seddon’s racism towards New Zealand Chinese today appears disgusting: he denied them state pensions, imposed stiff poll taxes on them and called them racial “pollutants.”

I asked a good friend who is a Professor of Chinese if Seddon should go. She replied: “I’m probably more conservative than you on this issue. For me, we should leave the statues alone and they are only and can only be partial representations of history. Destroying statues doesn’t destroy historical injustice or biased historical narratives. Besides, historical fashions come and go. The Russians and the Chinese have destroyed enough statues but failed to rectify any historical wrongs. So, for me, debate historical figures and events as much as one likes but leave material historical remnants alone. I guess that also answers your question about Seddon. The statue can also enable a conversation about racism in NZ.”

Wise words, don’t you think?

Conclusion

Statues and monuments are art, they are heritage – and sorry, Professor Richard Evans, as a historian you need to realise they are also fascinating and insightful, highly charged historical documents. And unless they are Gilbert & George, statues can’t answer back when abused by the crowd. What we should do with them will be addressed by subsequent speakers, but I personally advocate additional plaques or virtual ones through QR codes and apps to spell out the case for people’s perceptions today. Conciliation not confrontation, love not war, and thank you Church Monuments Society, don’t expunge, explain. And, last but not least, heed the watchword of the PSSA, “retain and explain.”

Dr. Mark Stocker is an art historian and art curator who lives in New Zealand. His publications are on Victorian public monuments, numismatics and New Zealand art. His recent book, When Britain Went Decimal: The Coinage of 1971, will be published by the Royal Mint in 2021.

The image shows, “Pulling Down the Statue of George III in New York City,” by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel, painted in 1859.