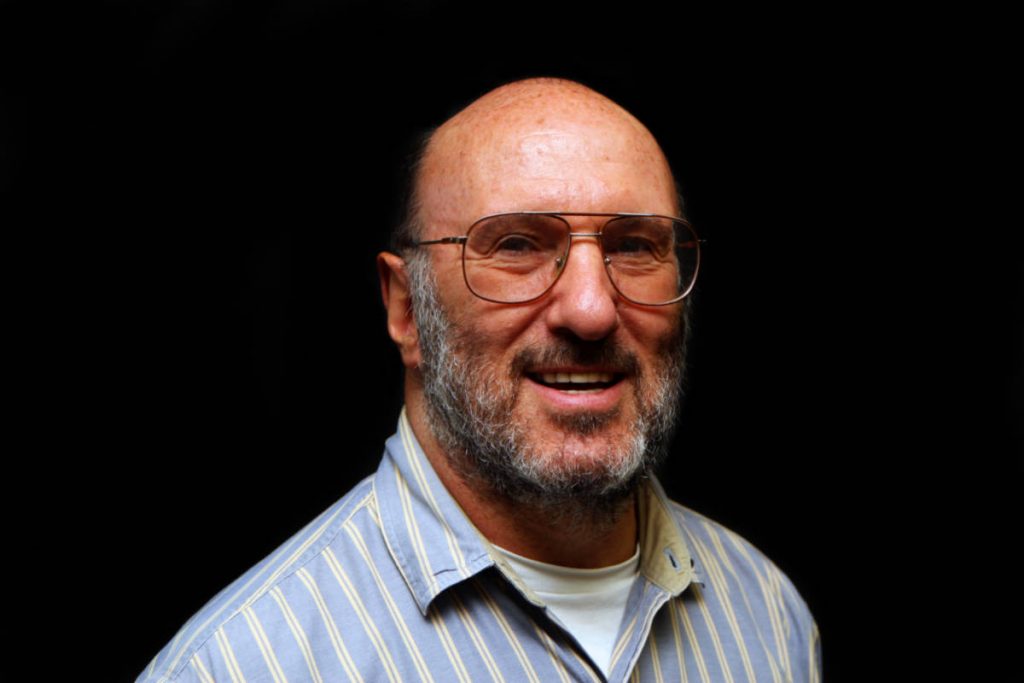

We are greatly pleased and honored to present this conversation with Professor Walter Block, the leading libertarian thinker in the US. Professor Block holds the Harold E. Wirth Eminent Scholar Endowed Chair at Loyola University New Orleans. He is the author of over two dozen books and more than 600 articles and reviews. Just recently, a petition was started by some Loyola students to have Professor Block fired for his “views.” Professor Block (WB) is here interviewed by Dr. N. Dass (ND), on behalf of the Postil.

ND: Welcome to the Postil, Professor Block. It is a pleasure to have you with us. For the benefit of our readers, who may not be aware of what has been happening to you at Loyola University, New Orleans, would you please tell us how the Cancel Culture decided to come after you?

WB: A Loyola student, M. C. Cazalas, who had never taken any class of mine, not ever once spoken to me, started a petition to get me fired for being a racist and a sexist. As of 8/5/20 she garnered 663 signatures, some of them Loyola students, but not all of them. An actual former student of mine, Anton Chamberlin, started a counter petition to get me a raise in salary. As of this date it has been signed by 5,646 people, again some of them Loyola students, but not all of them. I’m not likely to be fired for two reasons in addition to this gigantic signature disparity. One, I have tenure; that still means something, even in these politically correct times. Two, the president of Loyola University, Tanya Tetlow, bless her, responded to this get me fired initiative with a statement strongly supporting academic freedom and intellectual diversity. She and I do not see eye to eye on political economy, so this is even more of a credit to her than would otherwise be the case.

ND: What do you think lies behind this Cancel Culture? Is it a failure of education? Is it an excess of humanitarianism? Or, it is simply an expression of student radicalism, which has always been part-and-parcel of university life?

WB: My guess is that all of these explanations you mention play a role. According to that old aphorism, “If a man of 20 is not a socialist, he has no heart; if he is still a socialist at 50, he has no brain.” There must be something in human development that renders young people more vulnerable to socialism, cultural Marxism, cancel culture, snowflakeism, micro aggression fears, etc., than their elders. Unhappily, far too many middle aged and older people also succumb to the siren song of socialism. I think the general explanation for this general phenomenon is biological: most of us, except for a few free enterprise mutants, are hard-wired for government interventionism. A zillion years ago, when we were in the trees or in the caves, there was no biological benefit to be open to free enterprise, markets, capitalism. Hence, these genes had no comparative advantage.

ND: Should we regard Cancel Culture as dangerous? Is freedom really in peril? Such questions come to mind, given the tragic end of Professor Mike Adams.

WB: Yes, very dangerous. Economic Marxism was a dismal failure. Everyone can see the results in Cuba, North Korea, Venezuela, the old USSR, Eastern Europe, Mao’s China. But cultural Marxism is more insidious; it is more difficult to see its errors. Yes, there are racial and sexual divergences in wealth and income, and it is far too easy to attribute these results to economic freedom.

Poor Mike Adams. His is an extreme case, since he committed suicide, presumably due to the Cancel Culture. But apart from his demise, that case is only the veritable tip of the iceberg. There are hundreds if not thousands of academics who have been canceled, fired, forced to endure re-education camps, demoted, etc. The university with but very few exceptions is now a totally owned subsidiary of people who call themselves “progressives.” They really should be called “retrogressives” since they oppose civilization, freedom, prosperity. That is, they are really opponents of human progress.

ND: Lenin famously said that Communism was Socialism plus electrification. Likewise, can we say that the Cancel Culture is Socialism plus the Internet?

WB: Wow. That’s a good one. I wish I had thought of it. I’m grateful to you for sharing it with me. Before the internet, there were NBC, CBS, ABC, the New York Times and the Washington Post. Between them, they almost totally dominated the culture; they had an important impact on the outlook of the nation. Now, with the internet, one would think there would be far more heterogeneity. And, to some degree, there is. But the main players, nowadays, that “Big Five” now plus the electronic major media, keep canceling out libertarian and conservative voices. This does not constitute censorship, only government can do that (on the other hand, it cannot be denied that they are dependent on the state for favoritism). But until and unless people with divergent views set up successful alternatives, the voices of the left will continue to dominate.

ND: The student petition against you cites, among other things, your supposed “defence” of slavery. Of course, this is a misunderstanding of your position. Perhaps you could clarify for our readers what you actually say about slavery, especially the concept of the voluntary slave contract, which indeed goes back to the Classical world.

WB: Suppose, God forbid, my child had a dread disease that would kill him. He could be saved, but only at the cost of $10 million. I do not have anything like that amount of money. You, on the other hand are very rich. You’ve long wanted me to be your slave. So, we make a deal. You give me these funds, which I turn over to the doctors who save my child’s life. Then, I come to your plantation to pick cotton, give you economics lessons. You may whip me even legally kill me if I displease you. As in all voluntary interactions, we both gain, at least ex ante. I value my son’s life more than my freedom. The difference between the two is my profit. You rank my servitude more highly than the money you must pay me for it, and you, likewise, gain the difference.

Is this a valid contract? Should it be enforced? This is highly controversial even in libertarian circles, but in my view, you should not be accused of assault and battery if you whip me, nor murder if you kill me, since I have given up my legal right to object (this is very different than indentured servitude, which does not allow for bodily harm).

In 2014 The New York Times interviewed me about libertarianism (they were doing a hit piece on Rand Paul), and I gave them this example as a hypothetical. They quoted me as saying that actual slavery, of the sort that existed in the US up until 1865, was legitimate. I sued them for libel. We settled the case. I received monetary compensation, plus an addendum to their original article. It reads as follows: “Editors’ Note: Aug. 7, 2018. An earlier version of this article referred imprecisely to the views of Walter Block on slavery. While Mr. Block has said that the daily life of slaves was ‘not so bad,’ he opposes slavery because it is involuntary, and he believes reparations should be paid.”

I defended, only, this hypothetical slavery, in order to draw out the logical implications of voluntary interaction. As for actual slavery, it is an abomination, an evil, a horrid rights violation. That the New York Times would write as if I favored the latter, when I only supported the former, certainly counts as “fake news.”

ND: Given the fact that you are the foremost libertarian thinker in the US today, and your book series, Defending the Undefendable I and II, which came out in 1976 and 2008 respectively, is widely regarded as a libertarian “cult classic,” from a libertarian perspective, is Cancel Culture a just use of political and social coercion?

WB: You are very kind to say that of me. Thank you. There is no one who hates cancel culture more than me. I am tempted to say that it is coercive. It is, but only indirectly. Suppose all universities, without exception, were privately owned, and under the control of faculties and administrations all of whom were leftists. They did not relish heterogeneity of opinion, and thus only hired professors, outside speakers, invited visiting scholars, who represented their viewpoint. Would this be coercive? Of course not. People should have the right to do as they wish with their private property, provided, only, they did not violate the persons or property rights of others. Religious organizations, nudists, tennis players, all have the right to exclude those who do not subscribe to their tenets. However, the cloven hoof of government is all over the educational system. It is based on coercive taxation. “He who pays the piper calls the tune.” Money mulcted from the long-suffering taxpayer is funneled into institutions of higher learning, where Marxist studies, feminist studies, black studies, queer studies, are the order of the day. It is only due to coercive taxes that Cancel Culture is coercive; but for this element, it would not be.

Of course, without government putting its big fat thumb all over education, there would be more intellectual diversity in this industry. So the cure for the Cancel Culture is separation of education and state, similar to what all men of good will support in another arena: separation of church and state.

ND: This brings us to the nature of education itself. Is there a proper libertarian theory of education, given the underlying libertarian idea that any acceptance of an institution is enslaving?

WB: Yes, there is indeed a proper libertarian theory of education: it should be totally privatized. My motto is, “If it moves privatize it, if it doesn’t move, privatize it; since everything either moves or does not move, privatize everything.” I have applied this aphorism to pretty much everything under the sun in my publications, including streets and highways, rivers and oceans, space travel and heavenly bodies. Certain, I would include education under this rubric. Information generation should be as private as bubble gum, haircuts, piano lessons, shoes or cars. You want some, pay for it. You want to offer your services in this regard? Open up a school and attract customers.

But what about the poor? Will they not get an education? Of course they will. They obtain bubble gum, haircuts, piano lessons, shoes and cars; schooling would not be an exception. For people who are too poor, the tradition in private education, at whatever level, was to award scholarships to bright recipients. There would be no such thing as compulsory education (a 12 year prison sentence for those whose inclination leads them to want to work instead), any more than there should be compulsory purchase of bubble gum, haircuts, piano lessons, shoes or cars. Any acceptance of any coercive institution may not be enslaving (we should reserve that word for far more serious rights violations), but it is despicable. Education should not be an exception to the general rule of privatization.

ND: Perhaps we can draw back a little and turn to some larger issues. You describe yourself as an Austrian School economist. Would you please explain what that is?

WB: Austrian economics has no more to do with that country than Chicago School economics involves that city. It is so named because its originators, Menger, Bohm-Bawerk, Mises, Hayek, all were born there. It is sometimes called the free enterprise school of thought, since the public policy recommendations of virtually all of its practitioners strongly support economic freedom, private property rights, laissez faire capitalism. But Austrianism is an exercise in positive economics, not the normative variety.

Its main contribution is that economics, properly understood, is not an empirical science, but, rather, an exercise in pure logic. It starts with certain basic premises which are necessary and undeniable, and deduces all of economics from them. For example, man acts. To deny this is itself to perform a human action; therefore the criticism necessarily fails. Austrian economics consists of synthetic a priori statements, which are both necessarily true and also have real world implications; they explicate economic reality.

We have already mentioned one of them above: all voluntary trade is necessarily mutually beneficial at least in the ex ante sense. Here is a more pedestrian example. I buy a shirt for $25. I inescapably value it more highly than that amount, otherwise I would not buy it. Well, there was something about that shirt, maybe not the shirt itself, that I ranked in that manner. Perhaps I had pity for the shirt salesman, or wanted a favor of him, etc. Ditto for him. He valued my money more than the shirt, so he also profited. The Marxists might say this is (mutual?) exploitation (perhaps the richer person always takes advantage of the poorer one?), but this is abject nonsense. Voluntary exchange is not a zero sum game, where the winnings of the winners must equal the losings of the losers. No, in commercial interaction, both parties gain, otherwise they would not agree to participate.

Since laissez faire capitalism consists of nothing more or less than the concatenation of all such events (buying, selling, renting, lending, borrowing, gift giving), we may conclude is it necessarily beneficial to all participants. True, ex post either party may later come to regret the commercial interaction, but that is entirely a different matter. Can we test this economic law? The mainstream would aver that if we cannot, it is not a matter of science. Well, yes, it is not a matter of empirical science, rather, it is an aspect of logic. No one in his right mind “tests” the Pythagorean Theorem, or that triangles have three sides or the claim that 2+2=4. But that doesn’t mean these laws are not “scientific” in the sense of providing important true knowledge about reality.

Austrians also disagree with mainstream economists on a whole host of other issues. For example, monetarism (we tend to favor free market money, not fiat currency), business cycles (we claim they emanate from government money and interest rate mismanagement, not markets), monopoly and anti trust (Austrians see no role for the latter), indifference, cardinal versus ordinal utility, interpersonal comparisons of utility (mainstreamers support, Austrians oppose).

ND: The term “fiat money” is much bandied about nowadays. Is the concept of fiat money misunderstood or misused, given that money as the legal tender of a state does give paper money legitimacy as a medium of exchange? Or do you think such legitimacy does not exist?

WB: Milton Friedman was the host of the justly famous “Free to Choose” television series. However, when it comes to monetary matters, this scholar’s views are not at all compatible with that title. Most times when people were really free to choose the financial intermediary which overcomes the double coincidence of wants, they selected gold (and sometimes silver). Nevertheless, Friedman was a fervent opponent of this free market money. Why? Because it costs resources to dig it up initially, and more to store it. These expenses could be almost entirely obviated with fiat money, created by the printing press and/or central banking, he argued. But shoes, fences, chairs, also cost money. The proper question is not Can we reduce expenses? Rather, it is, whether or not these outlays are worth it? Even more important, the issue is, Who gets to choose whether or not they are worthwhile? Central planning oriented Friedman chose to ignore the decision in favor of gold of the free market; he urged the imposition of fiat currency.

Why do statists support this type of currency? There are three and only three ways for the state to raise funds. First, taxes. But everyone knows full well, even low information voters, who is responsible for that. Hint: it is not the private sector. Second, borrowing. Ok, those with the meanest intelligence might not be too sure of who is behind this mode of finance; but everyone else knows it is the government. Third, fiat money, created out of the thin air by the state apparatus. The beauty, here, from the point of view of the centralists, is that the resulting inflation can be blamed on all and sundry: on capitalist greed, on nasty consumers buying too much, even on otherwise beloved labor unions. Economists in the pay of government always stand ready to demonstrate that the correlation between prices rising and the stock of fiat currency in circulation is not a perfect one. Well, of course it is not, given varying expectations. But it is an insight of praxeology, the Austrian method, that the more money in circulation, other things equal, the higher prices will be.

ND: Much of your work centers upon anarcho-capitalism. Would you explain how you understand this concept, and why you feel it is important? And how would you answer the charge that anarcho-capitalism is utopian?

WB: Anarchism is important, because one of the basic building blocks of the entire libertarian edifice is the non-aggression principle (NAP). This means that all human interaction should be voluntary. No one should coerce anyone else. But the government, necessarily, engages in taxation. That is, it levies compulsory payments. One of the beauties of libertarianism is its uncompromising logic. Its willingness, nay, passion, to apply the NAP to all economic actors, with no exceptions. Well, if we apply the NAP to the state, we can see that the latter fails. Oh, their apologizers have all sorts of excuses. The income tax is really voluntary. Tell that to the IRS! That taxes are akin to club dues. Yes, if you join the tennis or golf club, you have to pay dues. But you agreed to do so. In sharp contrast, no one ever contracted to be part of the US “club.”

The “capitalist” part of “anarcho-capitalism” is also important. It distinguishes us from the left wing or socialist anarchists such as Noam Chomsky. They oppose the government, to their credit, but would also outlaw profits, money, private property, charging interest for loans, etc., in violation of the NAP. It also, very importantly, separates us from the Antifa and Black Lives Matter anarchists who are currently trying to take over streets, highways, and large swaths of Seattle, Portland and other US cities. They, too, oppose free enterprise.

Is anarcho capitalism utopian? Well, yes, I think it is in some sense. That is, due to my understanding of sociobiology, I don’t think a majority of people are now capable of living up to the NAP which underlies this system. On the other hand, the nations of the world are now in an anarchistic (not anarcho-capitalist) relationship with one another. A state of anarchy now prevails between Argentina and Austria, between Brazil and Burundi, between Canada and China, etc. That is, there is no world government controlling their interactions. The only way to solve this anarchism would be to install a world government. So anarchism is not utopian in the sense that very few people would want to go down that path.

ND: Some of the thinkers crucial to libertarianism, such as, Ayn Rand, Robert Nozick, Friedrich Hayek, James Buchanan, Ludwig von Mises and Milton Friedman favor limiting the reach of government. Anarcho-capitalism, on the other hand, seeks the end of government itself. How do you reconcile this fundamental difference?

WB: I don’t reconcile it at all. I am a big fan of all the scholars you mention. On a personal matter, it was Ayn Rand who converted me to a position of limited government libertarianism, or minarchism. I met her while I was an undergraduate at Brooklyn College, and, then, a blissfully ignorant enthusiast of socialism. I have learned from all of the authors you mention. However, they are all statists, of a limited variety to be sure, but statists, nonetheless. Instead, I would say that the thinker now most crucial to libertarianism in general, and to anarcho capitalism in particular, is Murray N. Rothbard. I am a Rothbardian, and I follow him in rejecting the criticisms of anarcho capitalism offered by the half dozen scholars listed above.

ND: In your important analysis of the pay-gap between men and women, you have come under fire from feminists who say that you do not take into account that as supposed patriarchy disappears, the pay-gap decreases. What do you say to such critics?

WB: Thanks for your characterization of my analysis. Actually, I have done only just a little bit of actual research on this matter. Rather, I am a follower of Gary Becker, Thomas Sowell, and Walter E. Williams on this issue who have done far more than I on this matter. I will take credit, however, for popularizing this analysis.

What’s going on here? Roughly, there is a sexual pay gap of some 30%. This means, again on average, that for every $10 a man earns, a woman’s pay is $7. What determines wages in the first place? Productivity. This divergence should not raise hackles when it occurred two centuries ago. Why not? Because male productivity then way higher than female. Most jobs required physical strength, and men, again only typically, are stronger than women.

But nowadays, very few employment slots require brute strength. So why does the gap still occur? It is simple; wives do the lion’s share of housekeeping, cooking, cleaning, child care, shopping, etc. But everything we do comes at the expense of not being able to do other things as well, if at all. Ussain Bolt is the fastest sprinter on the planet, but he is not a good cellist; Yo Yo Ma plays that instrument exquisitely, but his time in the 100 meters is nothing to brag about. This marital asymmetry specialization, alone, explains virtually all of this 30% pay gap.

There are two bits of evidence that support this contention.

Yes, the pay gap between all men and women is some 30%. But that between ever married males and females, people who are now married, widowed, separated, or divorced, is much higher. It varies, but is something like 60%. What is the pay gap between men and women who have never been touched by the institution of marriage? They are not married, widowed, separated or divorced. It is zero. Let me repeat that. There is no pay gap here. Now, in actual research, you never find 100% equality. A more accurate way of putting this is that the ratio between male and female earnings ranges from something like 90% to 110%, depending upon country, age, occupation, schooling, etc. But, for all intents and purposes the gap simply does not exist for the never marrieds.

Here is a second bit of evidence countering the claim that free enterprise is inherently sexist. Suppose this gap really were due to discrimination against women. Then, we would have a situation where the productivity of both genders was $10, but the fairer sex was paid only $7. But this would mean that industries where women predominate would be more profitable than others. There is no evidence supporting this. It would also imply that extra profits could be garnered ($3 per hour) from hiring a woman. As entrepreneurs added women to their payrolls, their wages would inevitably rise. To what level? To equality, since pay scales tend to reflect productivity, which we now assume are equal. But we see no indication that firms are beating the bushes to employ more women, except, recently, when the virus of virtue signalling began to predominate.

If patriarchy, defined as unequal household and child care tasks were to end, then, yes, the pay gap would also decrease, presumably almost to zero, since the marital asymmetry hypothesis would no longer be operational. But not quite. Pregnancy and breast feeding will always separate the genders. Then, too, men tend to take more dangerous jobs, and this too, will separate sexual remuneration. However, if the end of patriarchy is defined more broadly, so as to obviate these differences too, then I would expect the gap to disappear. But this is not the world we live in. Biology, once again, intrudes the best laid plans of the feminists. There are still strong differences between males and females. Many would say, thank God for the difference!

ND: In your view, is capitalism weakening, especially given how easily Communist China has exploited it for its own gain?

WB: Weakening? I would say the very opposite. The Chinese economy has catapulted thanks in large part to their adoption of at least some aspects of capitalism. The Russians, too. This is evidence, I think of a strengthening of this system.

ND: How do you think capitalism will manage tech monopolies

WB: Capitalism is incompatible with monopoly. If there is monopoly in existence then, to that extent, there is no capitalism. But to make sense of this claim we must have the Austrian view of monopoly in mind, not the mainstream or neoclassical one. What is the difference between the two?

In the (correct!) Austrian perspective, monopoly is a government grant of exclusive privilege to conduct a certain kind of business; anyone who competes with this monopoly is a criminal. Examples include the US post office and the system of taxi cab medallions which operates in major cities such as New York. Those who engage in such activities without permission from the monopolist are subject to fines and imprisonment. A very dramatic example of this phenomenon was depicted in the movie Ghandi when people went to the sea to obtain to water so as to access the salt therein. They were savagely beaten by the police. Why? There was a monopoly of salt granted by the British government, and these people were violating it. That is crony capitalism, not laissez faire capitalism.

Given this, there is a serious question as to whether or not there are at present any tech monopolies. Some are given special legal privileges by government, and, to that extent are monopolisitic, and thus, entirely incompatible with laissez faire capitalism.

The (incorrect!) view prevalent amongst most modern economists is very different. They would include the foregoing as monopolies but also, quite fallaciously, add on density or concentration. For example, when IBM was the only producer of computers, it was deemed a monopoly, based on the fact that it was the only one in this industry. This company never came within a million miles of trying to forbid competition (the Austrian perspective); it was deemed a monopoly solely because at the time it was thought to have no competitors. It had 100% “control” of the industry.

This concept is intellectually dead from the neck up. It is arbitrary. It depends upon how the “industry” is defined. If narrowly enough, pretty much anyone can become a monopoly; if widely, then no one is or can be. For example, I am the sole producer of Walter Block services, narrowly defined. There are other libertarian economists, to be sure, but none are exactly like me. On the other hand, if we define this “industry” broadly, I am only one of several hundreds of thousands of practitioners.

Let us take a less unique example. If the industry is defined as providing dry breakfast cereals, the concentration ratio will be high. If we include wet breakfast cereals too, this ratio will be lower. If we add all breakfast ingredients, ham and eggs, not just cereals, it will decrease even more. Adding all food, not just for breakfast, will further reduce it. Well, which is correct? Plaintiffs want to define the industry narrowly, so as to render a high concentration ratio, or monopolization, whereas the defense sees the matter in the opposite way. The point is, there is no rhyme or reason to this entire matter.

Bill Gates and Microsoft started way out in the boonies in Seattle. He didn’t grease the palms of either party in Washington DC. How to bring him into line? Why, declare him a monopolist! All of anti-trust legislation is a disgraceful sham.

ND: What about encroaching robotization? If human labor is largely side-lined, what will capitalism become?

WB: I am not a Luddite. I do not think that machinery, computers, robots, etc., are a threat to human kind. Indeed, I maintain that the very opposite is the case. The more non human help we can access from such sources, the less will our lives be “nasty, brutish and short.”

Either we will run out of jobs that need doing, or we will not. In neither case will artificial help emanating from this source prove to be a difficulty. Suppose we become aesthetes, and are satisfied with our present standards of living, a few decades from now. Then, we will have a achieved a “post scarcity” state of the economy. Thanks to machines, and everyone will have a sufficient number of them, we can all sit back, relax, and “play” all the livelong day. No problem here. More realistically, we will never run out of thing we want. We will always seek more than we have. We will want to eradicate all diseases, live forever, comfortably, explore the core of the earth, the bottom of the oceans, other planets in this and additional solar systems. With the help of robots, we can accomplish more of these goals than other wise, but we humans will still be called upon to labor so as to attain, these ambitious goals.

Ned Ludd was faced with knitting machines which would allow one worker to do the jobs previously needing 20 people. He “reasoned” that 19 people would then be rendered unemployable, and proceeded to burn this new machinery. His heart may have been in the right place (if we abstract from the fact that he destroyed the property owned by others), but the same cannot be said for his head. He reckoned in the absence of the fact that these 19 people would now be freed up to create new goods and services, impossible to attain previously, but now within our reach.

But the same exact situation presents itself right now. Instead of looking at the secretaries and typewriter workers unemployed by computers, those. who labored for Kodak and are no longer needed, ditto for zoom reducing the need and the employment needed for travel to attend meetings, focus on the fact that all these “unemployed” people are now free to produce goods and services otherwise unobtainable. At one time, about 85% of the US labor force was needed to be on the farms, in order to feed ourselves. Nowadays, the figure is something like 2%. Is this a tragedy for our economy? To think so is to revert to simple Ludditism. It is a failure to understand basic economics. The more help we get from inanimate matter, the better off we shall be

ND: As an economist, are you hopeful about the future of the West?

WB: Milton Friedman was once asked, What is the future course of stock market prices? His response was, They will fluctuate. I say the same thing as the future of the West. It, too, will fluctuate, I expect. If Biden wins the next election, political correctness will threaten Western civilization. If Donald, less so. My hope is that Rand Paul will be the president in 2024. Then, our civilization will take a turn for the better.

ND: Thank you so much for your time. It was wonderful speaking with you.

WB: My pleasure. Thanks for putting these questions to me. They were challenging, and made me think.

The image shows, “New York,” by George Bellows, painted in 1911.