The America of 2020 is a country in financial ruin. Its twenty-three trillion debt is the greatest of any country in history. Its political and social decline is obvious to anyone over fifty. Its universities, including the most distinguished ones, once the envy of the world, have been turned into meccas of ideological indoctrination.

Almost every aspect of America’s past greatness is gone. Until recently, one area of its cultural strength was unquestionable: Museum collections. American museums were once greatly admired by the curators of important European museums. But things are changing.

Some American museums embarked on a mission to suspend the purchase of European art, to sell items from their collections, or put them (temporarily) in storage rooms, in order to display the works of minority artists. In 2018, the Baltimore Museum of Arts, sold seven artworks “to make way for pieces by contemporary artists of color and women.” Years ago, the Walters Museum, made the decision to acquire more “Black Art.” “The new acquisitions,” we read, “reflect the efforts of the museum, established at a time when the city was predominantly white, to evolve with the city, whose population now is predominantly black.” This year, the Walters suspended the purchase of European art. What is happening in Baltimore is a wider trend that is sweeping across America.

Last year, when I went on my monthly visit to Baltimore Museum of Arts, five of my favorite rooms, one containing Corot and Couture’s portrait of a woman with exposed breasts, were closed. What I found instead were mediocre contemporary paintings of Black slaves in chains by a local contemporary minority painter. To make sure that the visitor gets the message, the paintings were accompanied by very long statements by the painter, written in activist gobbledygook.

Contrasting what I saw with my previous experiences, the sense of quiet joy that a museum visit causes, I felt deeply irritated. I had a strong feeling that whoever responsible for the decision of taking down the great masters had robbed me of something that my soul longed to see. Instead of peacefully enjoying the beauty of the old artists, I was punched with a loud social message. It was consistent with the “1619 Project” of The New York Times. However, what is justified in the case of a politically engaged newspaper should have no place in art museums, for that is where we go to contemplate Beauty.

Clearly, beauty is of no interest to the new generation of curators, who believe that a social massage is more important than the intrinsic, artistic value of the old masters. They do not see themselves to be guardians of Beauty, and of the past that must be very carefully preserved. They see themselves as propagators of their ideological vision of America.

American museums are becoming ideological peddlers, and if they will follow in the footsteps of educational institutions, we can expect the same disastrous results. Old masters, like the classic writers, will be replaced by “underrepresented” minority artists, or sold off and forgotten by the public.

This is what happened under communism. The Stalinist curators would store old masters’ paintings in storage rooms and display Socialist Realist paintings, or they would sell them. Philadelphia Museum, for example, acquired a Poussin that Leningrad museum sold in the 1930s. But as Socialism is making inroads into American life, we should not be surprised at what is happening in our art institutions. “Art must be ‘engaged’” was the message of Socialist Realism.

Why that was so is easy to understand, if we turn to the writings of the Founding Father of the Socialist Idea. As Marx taught us, art is an expression of social consciousness, and as the latter changes so does art. Standard art history books written by Marxist art historians in the former countries of real socialism would tell you that the medieval mind was the prisoner of a religious Weltanschauung, and that the medieval paintings, saturated with the Biblical scenes, are expressions of it.

Renaissance art, on the other hand, represents a shift in social consciousness, and a step in the right direction: The painters broke with the medieval idea of anonymity, and the exclusively religious worldview made room for non-religious topics, marking the birth of the individual. The painter no longer saw himself as someone whose talent is to be devoted to the glory of God, but as an individual who expresses his own individuality.

We were told, for example, that the presentation of the human body, or the nude, was an affirmation of this world. Afterlife was pushed out by the beauty of earthly existence. Another shift can be observed in 17th-century Dutch painting. Thousands of portraits of rich merchants and important men of politics marks the birth of the bourgeoisie—the new social class oriented not toward the hereafter but earthly concerns: money and politics.

Even the poor shepherds are no longer presented as humble folk who made their way into paintings in the scenes of the manger with the baby Jesus and the Holy Family. They can be seen on green meadows attending their grazing animals.

The story of the development of social consciousness continued till it reached the peak in what came to be known as Socialist Realism. Its main heroes were the neglected and forgotten: the worker and the peasant. Former socialist underdogs are today’s American minorities. Their images can be seen everywhere on mural paintings.

How important is Marx’s insight for our understanding of art? It isn’t. It says something obvious. To be sure, one can trace the trajectory of changing social consciousness just by looking at the products of the past epochs: They tell us something about the people who made them, the ideas that motivated them, and how different they were from us.

But Marx’s theory of social consciousness tells us nothing about art’s aim — Beauty. In making us believe that what we see in paintings is social consciousness, Marx made us forget its most fundamental aspect: Beauty, the way it is presented, the changing technique. The theme is important but it cannot be more important than the artistic execution.

The paintings of Delacroix, for instance, have a political dimension, but if we admire them it is hardly because they carry a political message. Delacroix was simply a great painter.

This is what the new curators seem to forget, and they need to ask themselves a very simple question: Are the canvases they spend millions on art or ideological statements? And if they want to educate the public, they will not succeed by making the public look at bad art. They have to know what clear-cut criteria of aesthetic judgment are.

They may be unaware of it, but they are behaving like the followers of Marx for whom History is a battleground between the oppressors and the oppressed, and it unfolds itself through various historical stages. Therefore, what we see in art of the past epochs is the record of forms of oppression, the way in which oppression operated, from its cruelest forms to its most subtle expressions of submission, as John Stuart Mill taught us in The Subjection of Women. Art, according to this theory, is not about “perfecting Nature,” as Aristotle would have it.

At best, it is a means of plastic expression of a social message. The old idea that the artist is a creator who expresses eternal Beauty with his brush or chisel is long gone. He is an unconscious peddler of false or unliberated consciousness, expressing the social values of his epoch. He is like a bourgeois jurist, who, in designing laws, is building ever-newer punitive devices that protect the privileged classes against the oppressed, rather than being someone who wants to bring universal rules of justice to the City.

Similarly, a painter, who is painting, say, a naked woman, as we learn from feminist criticism, is objectifying women (according to the standards of his epoch). “Objectification,” even if it is a mental act, or assumes the form of a painting, is oppressive. This reasoning leads us straight to Marx’s idea that History is a struggle between the oppressors and the oppressed.

If you still wonder why a mediocre painting could replace a Corot or a Couture, the answer is simple: A mediocre painting of a slave, “a man objectified,” breaking chains, shows the viewer a fight against alienated consciousness, social injustice, whereas Couture’s painting of a blushing woman with exposed breasts is likely to be interpreted as female submissiveness.

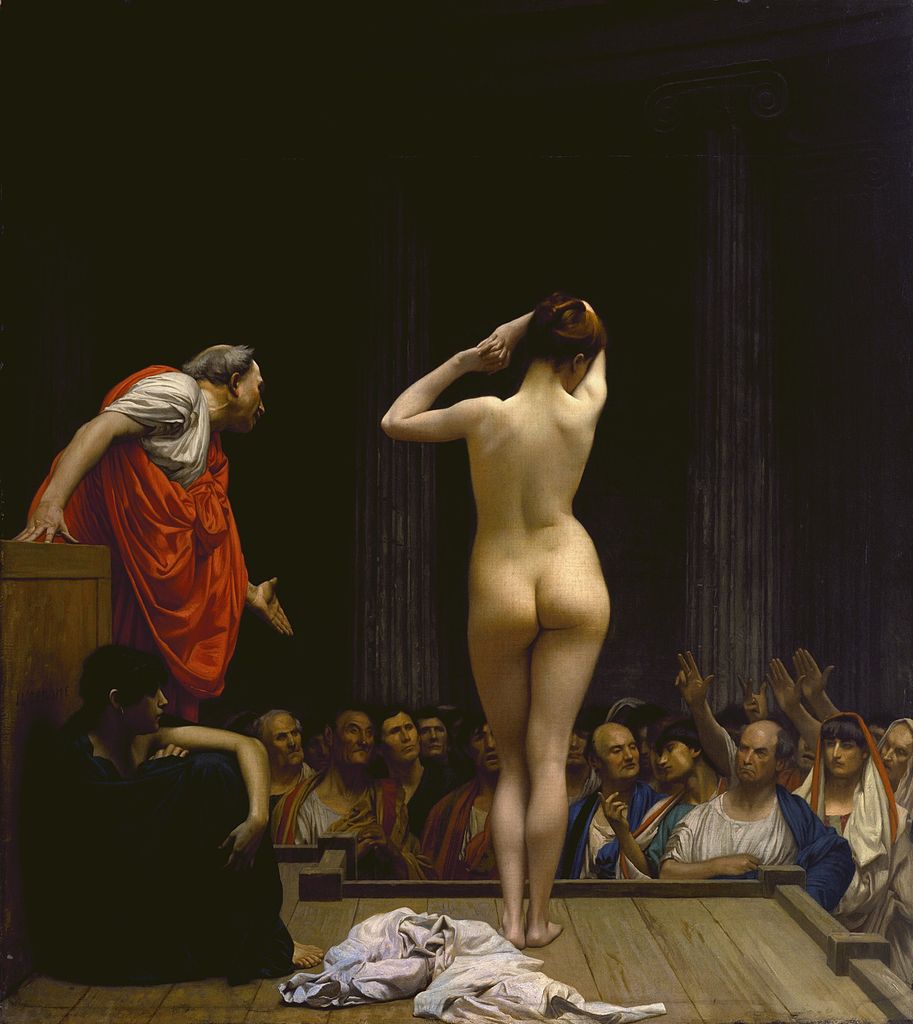

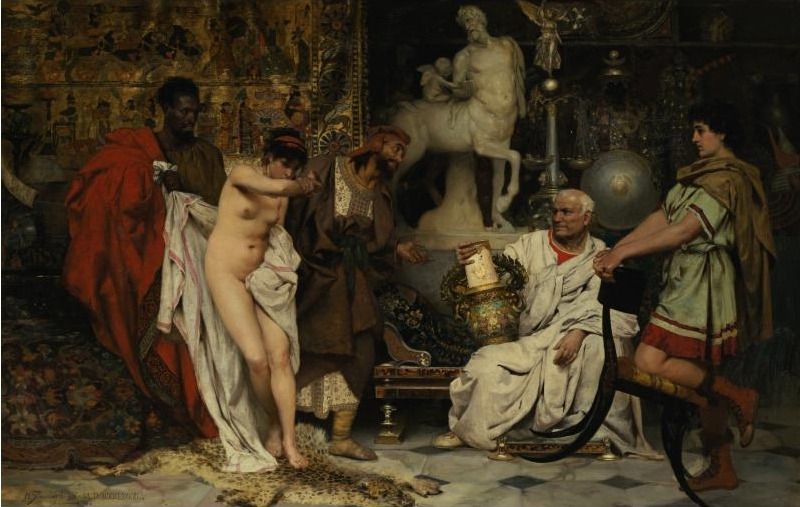

Feminists have been unambiguous in their claim that the female nude is an expression of “the typical male attitude,” of seeing a woman as an object to own. Hundreds of 19th-century Academic and Orientalist paintings, showing naked women sold at slave markets in ancient Rome or the Middle East, is supposedly a testimony of such an attitude of the male painters. Jean-Léon Gérôme (“Roman Slave Market”), Remy Cogghe (“Female Slaves Presented to Octavian”), or Hermann Corrodi (“The Slave Market”) may be invoked here as illustrations.

In each painting, a beautiful naked woman is presented to the buyers by the sellers. Orientalist paintings are more likely to be a rendition of what 19th-century Arab countries were like than the imaginary constructions of the Academicians who conceived of Roman slave markets. However, the question is not about the accuracy of the actual practice of slave trade in Rome or Middle East, but intentionality of artistic presentation.

Among many 19th-century paintings presenting naked slave women for sale, one seems to stand out. It is Henryk Siemiradzki’s “The Vase or the Woman.” The painting received the gold medal at the 1878 World Fair in Paris, and the painter was awarded the French Legion of Honor. The painting was very much liked by the Dutch-English painter, Sir Laurence Alma-Tadema.

The painting presents an older Roman patrician and his son. The older man is sitting, looking at the vase, while his son is looking at the young beautiful woman. One of the traders is showing the vase to the patrician; the other, a very tall Black man, is pulling a white long cloth covering the woman’s body. In what appears a gesture of covering her shame, the half-naked woman is putting her hand on her face and eyes, as if she wants to defend herself against the shame of her nudity.

What makes Siemiradzki’s painting different from similar paintings is that the buyer must choose either the woman or the vase.

How can one equate a woman with a vase, one can exclaim, unless one reduces a woman to the level of an object. But to say that is to miss the point Siemiradzki makes here. The woman and the vase are on the same level, if – and only if – there is a common denominator between the two. This denominator is beauty.

However, once we recognize it, the only logical choice left is to choose the vase. Its beauty will outlast the beauty of the young female body. It will live for centuries, long after the beauty of the girl and the girl herself are gone.

As we look at the painting, we notice that the beautiful young woman is of greater interest to the patrician’s son, who is glaring at her, rather than his father—an older man, who seems to prefer the vase, which he is holding.

However compelling, logic can be complicated. The young man would choose the vase but only if he followed Plato’s advice from the Symposium: “He who aspires to love rightly should from his earliest youth seek intercourse with beautiful forms.” But youth has its own logic. Its interest is passion: intercourse with a bodily form; interest in the intercourse with Beauty itself, or beauty of art comes later, in older age, when “the devil” (sexual passion), as Socrates teaches us at the beginning of the Republic, is gone.

Looking at Siemiradzki’s painting, one learns an important lesson: Art is not about lessons in raising social consciousness, nor is it about politics, social justice, representation of minorities. It is about Beauty. Unless present-day museum curators learn this lesson, they will quickly fill our museums with “loads of rubbish,” as the British say. The old elites which feed themselves on Beauty will look at it with predictable scorn, and the minorities which are the intended target of “minority art” will conclude that there are better things to do. Alas, they are likely to be right

Zbigniew Janowski is the author of Cartesian Theodicy: Descartes’ Quest for Certitude, Index Augustino-Cartésien, Agamemnon’s Tomb: Polish Oresteia (with Catherine O’Neil), How To Read Descartes’ Meditations. He also is the editor of Leszek Kolakowski’s My Correct Views on Everything, The Two Eyes of Spinoza and Other Essays on Philosophers, John Stuart Mill: On Democracy, Freedom and Government & Other Selected Writings. His new book, Homo Americanus: Rise of Democratic Totalitarianism in America, will be published in 2021.

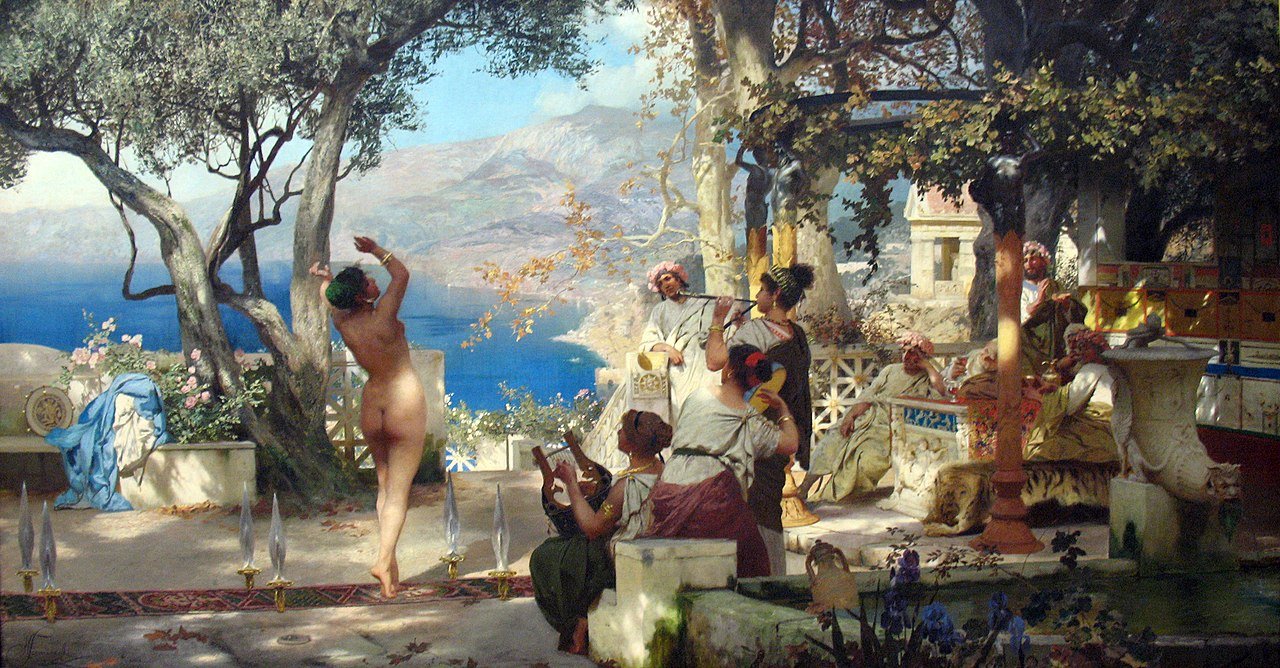

The image shows, “Dance Amongst Swords,” by Henryk Siemiradzki, painted in 1881.