This month the Postil is most pleased and honored to present this interview with Professor Jeremy Black, the prolific and influential British historian. Professor Black has added greatly to our understanding of Britain, Europe and America within the context of international affairs, as well as, diplomatic, military and cultural history. He is interviewed by Dr. Zbigniew Janowski, author of several books on Descartes and a forthcoming book Homo Americanus. The Rise of Totalitarian Democracy in America.

Zbigniew Janowski (ZJ): Allow me to begin with a short biographical note. Among your books are: Military Strategy: A Global History, The Atlantic Slave Trade in World History, Maps of War, Naval Warfare: A Global History since 1860, Naval Power: A History of Warfare and the Sea from 1500 Onwards, Rethinking Military History, The British Abroad: The Grand Tour In The Eighteenth Century, A History of the World: From Prehistory to the 21st Century, The Age of Total War, 1860-1945, Geographies of an Imperial Power: The British World, 1688-1815, War and the World: Military Power and the Fate of Continents, 1450-2000, Imperial Legacies: The British Empire Around the World, English Nationalism: A Short History, The British Seaborne Empire.

I missed “a few books”—or, more precisely, I did not list the 80 other books you wrote! In your bio, I found that you have authored 100 books. That’s more than what Paul Johnson, Arnold Toynbee or Guizot wrote. It is more than most, even very well-educated people, will ever read, let alone by a single historian. Are you writing, thinking what the potential reader should know, or are you answering your own questions?

Jeremy Black (JB): As you suggest, I have written more history books than any other British writer. I do not count them, but I think there are about 140 single author books, as well as three co-authored and quite a few edited. I obviously have a compulsion, but there is also a determination to rewrite what I think is poorly covered, at the very least offering a different interpretation so that no one can pretend that there is only one view, which is a flaw of the zeitgeist approach.

ZJ: In his The Idea of History, Robin Collingwood, following Voltaire, says that the idea of “Philosophy of History” means “a critical or scientific history, a type of historical thinking in which the historian made up his mind for himself instead of repeating whatever stories he found in old books.”

The Positivists claimed that there are general laws governing the course of events. Thucydides, Joseph Flavius, Dio Cassius, Procopius of Caesarea, and others on the other hand, say that the task of history is to preserve great human deeds from falling into oblivion. Do you subscribe to any of the above “schools”?

JB: I do not think that there are general rules in the writing of history, as it depends on the complex interaction of cultural and temporal contexts, individual approaches, and the particular issues at stake in specific topics. For each book, I consider the task I have set and the audience I have in mind, and I try to write and reason accordingly. The space available is also a key point. The analysis of documents can be scientific, but that of humans is necessarily more limited.

ZJ: So, let me follow up on your claim that there are no general rules in the writing of history. John Stuart Mill, who is hardly ever mentioned as a philosopher of history, claims that most of mankind has no history properly speaking. What he means by that is that history is more than chronology, and to turn chronology into history there must be an engine that drives it for history to develop. Otherwise we deal with static civilization, like China, which he uses as an example. Several thousand years and nothing, or not much. The same can be said about ancient Egypt, which Mill does not mention, but which falls under the same category of static civilizations.

If we look at, for example, sculptures, they seem to be the same for two thousand years. If we go to ancient Greece and compare the development of sculpture and vase design, from the white geometric style in 800-700 BC, to the Classical period, and the almost flamboyant, expressive, emotional Hellenistic style in 4th-century BC (Pergamon reliefs, for instance), we see fantastic “progress” or change in design and expression. Greece changed; China and Egypt did not.

Is Mill’s insight essentially correct? That is, to have history we need to inject the idea of progress into chronology?

JB: I see History as the Past, how we tell stories about the past. Neither in my view is inherently progressivist and I would argue separately that that is the conservative position; but then I am a committed conservative.

ZJ: Let me move to something you wrote about in The British Seaborne Empire. There you claim that in the middle of the 19th-century, Britain applied the new technology more successfully than other European powers, and its industrial production motivated the Empire to expand. However, this insight explains 19th-century expansion. What were the earlier motivating factors, and were they the same that made others seek to build empires?

JB: A quest for trade, a sense of destiny and a feeling of Christian providential is the same three for Portugal and Dutch.

ZJ: You mention what you call “gentlemanly capitalism,” which places emphasis not only on manufacturing of goods, but on finances, insurance etc., what we could call today infrastructure, which is connected with social values. Those values were propagated by the graduates of the British schools. Would you say that there were in fact two empires: one heavily industrial and the other “cultural,” which disseminated the British values (not necessarily intentionally), and that in doing so the British exported their value system to one fourth of the globe?

JB: I would agree entirely. To be effective an imperial system has to have an attractive ideology, else it relies on force and coercion which does not work in the long term as the continued free spirit of Poland shows.

ZJ: Here is a fragment from the description of your book, English Nationalism: A Short History: “Englishness is an idea, a consciousness and a proto-nationalism. There is no English state within the United Kingdom, no English passport, Parliament or currency, nor any immediate prospect of any.” Sir Roger Scruton in his England: An Elegy made what I believe to be a similar claim: England did not succeed in creating a nation, but, rather, Home for the English.

JB: That does not mean that England lacks an identity, although English nationalism, or at least a distinctive nationalism, has been partly forced upon the English by the development in the British Isles of strident nationalisms that have contested Britishness, and with much success.

So, what is happening to the United Kingdom, and, within that, to England? I look to the past in order to understand the historical identity of England, and what it means for English nationalism today, in a post-Brexit world. The extent to which English nationalism has a “deep history” is a matter of controversy, although he seeks to demonstrate that it exists, from ‘the Old English State’ onwards, predating the Norman invasion.

I also question whether the standard modern critique of politically partisan, or un-British, Englishness as “extreme” is merited? Indeed, is hostility to “England,” whatever that is supposed to mean, the principal driver of resurgent English nationalism?

The Brexit referendum of 2016 appeared to have cancelled out Scottish and other nationalisms as an issue, but, in practice, it made Englishness a topic of particular interest and urgency, as set out in this short history of its origins and evolution.

ZJ: What you said makes me wonder whether the reason for Asian civilizations not expanding or building empires lies in a very different character of Eastern religions. After all, around the same time, say 1500, Asia (China, Japan, India) was in some respects more advanced than Europe: Small continent, very divided, small kingdoms, principalities. Asia, viewed from above, appeared to be a better candidate to dominate the world than the West.

JB: You are absolutely correct. They were predominantly courtly and rural and hostile to mercantile interests.

ZJ: The British of 18th- and 19th-centuries did not study business, administration, finances, etc., the disciplines that are popular today. Yet, “reading” the classics or history, as you say of the UK, was fundamental in creating a frame of mind that was conducive in preparing a host of people to run the empire. What role did Classical education play in it?

JB: The Classical education that was dominant in England provided in the shape of Rome a model of imperial behaviour that was seductive in terms of British imperialism, but the mercantile order instead focused on experience-led understanding of opportunities.

ZJ: Since you invoked Poland, let me quote something that an Australian friend of mine wrote me recently: “I admire your energy, but cannot share in any optimism about the immediate future of the US or Western Europe – perhaps something from Central Europe, even Russia might be born – but I am with Kafka – yes there is hope but not for us. I am not trying to convince you – or anyone on this, I am just sharing what I see and feel about now and the future.”

Do you share my friend’s sentiment? I hear it often; the West—the US, Europe etc.—is lost; letting millions of immigrants who cannot assimilate was a mistake, the West abandoned its commitment to Tradition, history, values. Eastern European countries resisted and are in a better position to defend themselves.

JB: There is certainly a cultural crisis in the West, one linked to grave social issues; but the uncertainty of developments, the prime law of history, makes it impossible to predict the future.

ZJ: Does your claim about the rise of industrial production in 19th-century, which made Britain look to expand the empire, apply to China today? The new Silk Road, etc. inscribes itself well in what you said in your book. Is the mechanism the same, similar?

JB: China today has parallels to Britain’s pattern of growth, but is far more authoritarian.

ZJ: Let me move to another topic, but before I do, I would like to give you a few examples. In October 2017, Christ Church in Alexandria, VA, of which George Washington was a founding member and vestryman in 1773, pulled down memorial plaques honoring him and General Robert E. Lee. In a letter to the congregation, the church leaders stated that: “The plaques in our sanctuary make some in our presence feel unsafe or unwelcome. Some visitors and guests who worship with us choose not to return because they receive an unintended message from the prominent presence of the plaques.”

In August 2017, the Los Angeles City Council voted 14-1 to designate the second Monday in October (Columbus Day) as “Indigenous Peoples Day.” According to the critics of Columbus Day, we need to “dismantle a state-sponsored celebration of genocide of indigenous peoples.” Some of the opponents of Columbus Day made their intentions clear by attaching a placard on the monument: “Christian Terrorism begins in 1492.”

In June 2018, the board of American Library Association voted 12-0 to rename the Laura Ingall Wilder Award as the “Children’s Literary Legacy Award.” Wilder is a well-known American literary figure and author of books for children, including Little House on the Prairie, about European settlement in the Midwest. In a statement to rename the award, the Board wrote: “Wilder’s legacy, as represented by her body of work, includes expressions of stereotypical attitudes inconsistent with ALSC’s core values of inclusiveness, integrity and respect, and responsiveness.”

What is happening in America today sounds, to me, very familiar. As a former denizen of the Socialist paradise, I have the déjà vu feeling. Monuments were torn down, awards were renamed, etc. How do you explain these stunning similarities? To me, and I do not have a better explanation, things come down to History, the understanding of its essence.

History is seen as progressive, has a logic of its own and destroys its past; it condemns itself, its infancy for being immoral and discriminatory. The examples I gave you are American, but similar problems can be derived from the UK. I remember a controversy over the monument of Cecil Rhodes (the founder of a very prestigious scholarship for American and Canadian students) at Oriel College, Oxford, except that Oxford did not give in to the activists’ demands to remove it.

JB: I would prefer not to repeat what I covered in several books on the memorialisation of the past, which I commend to your attention, not least as they offer an account of historiography that is not limited to the narrow world of intellectuals. So, can I add a few contextual points?

A facile and inaccurate approach is to argue that battles over identity reflect the failure of the Marxist narrative and the competing ideologies of the twentieth century.

I am less sanguine. In part, I see a continuation in a new iteration of anti-Western Cold War narratives, especially of the Maoist type; in part The Long March through the Institutions, in part a narcissistic preference for present day emotion and sentiment over continuity, reason , and an understanding of the fecklessness of much current commitment, and in part a brilliant way by self-important monochromatic thinkers to advance their careers through polemic; monochromatic referring to a failure to see a full spectrum of arguments and polemic chosen rather than rhetoric.

ZJ: On September 1st, 2018, the Editors of a prestigious British Magazine the Economist, published “A Manifesto” to “rekindle the spirit of [liberal] radicalism.”

In it, we read: “Liberalism made the modern world, but the modern world is turning against it. Europe and America are in the throes of a popular rebellion against liberal elites, who are seen as self-serving and unable, or unwilling to solve the problems of ordinary people… For the Economist this is profoundly worrying. We were created 175 years ago to campaign for liberalism—not the leftish progressivism’ of American university campuses or the rightish ‘ultraliberalism’ conjured up by the French commentariat, but a universal commitment to individual dignity, open markets, limited government and a faith in human progress brought about by debate and reform.”

However sober the Economist’s statement appears, it is reminiscent of past declarations by the Communists (in 1956, 1966, 1968, 1971, 1980). After each crisis, they made their declarations to keep the faith in the health of communist ideology by blaming the former Party executive committee. The declarations found the classic expression in the slogan: “Socialism Yes, distortions No!”

Once again, as a historian, do you see analogy between Socialism and Liberalism?: “Liberalism Yes, distortions No!” Same problems, same explanations, same idea of blaming someone: the kulaks, the party members, the corrupt elites—but never the Idea, be it the Communist idea or Liberal idea.

JB: Liberalism, like Conservatism, is a mood as well as an ideology, and practices as well as precepts. Inherently, a Liberalism predicated on individual freedom had much to offer and there are contexts in the nineteenth century where Liberalism or at least Liberal causes were meritorious and remain attractive. Anti-slavery, opposition to censorship and support for religious freedom are prime instances. It is ironic to a degree but also a reflection of the ideological essence of the last century, that these ideas are now best advanced by Conservatives while the progressivist dimension of Liberalism has been transmogrified into an authoritarian statism that owes something to Socialism but is not restricted to it.

ZJ: Can there be a healthy conservatism in the US? As our friend Jonathan Clark argues, Americans have problems answering the question what should be conserved. The new country was founded as a rebellion against the Past, against the hierarchical order.

JB: The differing natures of ideological parameters are suggested by the contrast between The USA and Europe. In the former case, the competition has been between different conceptions of individualism with the ability to choose and change religious affiliation at will, a key form of individualism. Conservatism tends to be expressed in terms of hostility to government, hostility which indeed can have an anti-societal perspective and notably so if social norms are imposed. In Europe, notably Continental Europe, the understanding of society places less of an emphasis on the individual.

ZJ: We tend to see the PC movement in the US as an aberration, even insanity, and there is every reason to consider many of the claims made by the advocates of PC as insane. One can hear the call to dismantle “power structure” daily. Listening to the liberal rhetoric one often gets the feeling that oppression is real, as real as it was in 18th c. However, from a broader historical perspective one can see what is happening as further unfolding of the principles which were at work in 18th-century America

JB: There is no correct format, that indeed being a characteristic of Conservatism, being more pluralistic than the doctrinaire nature of the Left. As a British Conservative, I seek a middle way between the two, which incidentally helps explain my support for leaving the European Union. I am wary of government but keen on society.

ZJ: Let’s dwell for a moment on what you just said: As for the first part of your statement (“Conservatism tends to be expressed in terms of hostility to government”), the same thing can be said about Liberalism. You remember how German socialist, Ferdinand Lasalle, described the limited or Liberal government: Nachtwächterstaat—a night-watchman state, or, in the words of the British historian, Charles Townshend, as a “standard-bearer.” If I remember correctly, the opponents of the liberal states called their supporters the “minarchists.”

The sole duty of such a state was to prevent theft, enforce property laws, and provide security. This is not the reason why the Conservatives are hostile to government; they, as you said, are afraid of the government because it can be an instrument of the imposition of laws and regulations which are fundamentally hostile to the “natural order of things.” Can one say, then, that both parties differ with respect to what they see the function or role of the state should be, or why the state is there in the first place.

JB: The interaction, indeed melding of traditional conservatism and liberalism, has varied greatly and will continue to do so. In large part, this reflects contingent circumstances and the way in which they are debated and recalled, in short, the weight of history, but there is commonality of the issues posed by democracy and democratisation, as well as the particular inroads and challenges of Communism, Socialism, and Fascism. To a degree, these developments made classic liberalism redundant unless in a conservative context.

ZJ: With respect to how Liberals and Conservatives perceive the role of the State, can one say that the difference between the two lies in that the Liberals use the state to impose abstract social norms, whereas the Conservatives see the state as a guardian of the inherited order of the Past. Edmund Burke saw it when he talked about the “Empire of Reason,” “cold hearts.” This way of thinking underlies the idea of social engineering, that is, finding a method of molding reality into what the abstract reason, unrestrained by tradition, history, the Past, wants it to be. Thus, the Past—national history, national identity—is no longer something worth preserving, but a piece of clay in the hands of “experts” who know what social and political life should be like.

JB: You have expressed that very well. Macron is a liberal in these terms.

ZJ: Going off of what you just said. (In large part, this reflects contingent circumstances and the way in which they are debated and recalled, in short, the weight of history, but there is commanality of the issues posed by democracy and democratisation, as well as the particular inroads and challenges of Communism, Socialism, and Fascism. To a degree, these developments made classic liberalism redundant unless in a conservative context).

This raises a few interesting points, which I would like to phrase in the following way: First, redundancy. The appearance of the Socialist idea made Liberalism, or some of its propositions, redundant or even obsolete because socialism (not in the Stalinist version but in socialist-democratic version) could be said to have proposed them all, or made them look even better. Second, your redundancy thesis against the Conservative background also helps to explain why Liberalism appeared to be benign and made Conservatism look like a proposition which does not have much to offer.

For as long as Communism was threatening, Liberalism appeared to be attractive because it fought for individual liberties against its collectivist rival. With the collapse of Communism, Liberalism lost its urgency to defend the individual against the democratic collective, which de Tocqueville feared so much. Would you agree?

JB: I would agree completely, and would add that the challenge from liberalism has become more serious because of the ability of left liberals to control the mechanisms of the steadily larger public sector. This provides a different ethos for statism to that of Communism, but it is statism nonetheless.

ZJ: I want to quote something to you. It surprised to me how few people noticed the similarity between Marxist and Liberal understanding of history. Here is the first passage: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles. Freeman and slave, patrician and plebian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed, stood in constant opposition to one another, carried on an uninterrupted, now hidden, now open fight, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary reconstitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.

In the earlier epochs of history, we find almost everywhere a complicated arrangement of society into various orders, a manifold gradation of social rank. In ancient Rome we have patricians, knights, plebeians, slaves; in the Middle Ages, feudal lords, vassals, guild-masters, journeymen, apprentices, serfs; in almost all of these classes, again, subordinate gradations..”

And here is another passage: “The entire history of social improvement has been a series of transitions, by which one custom or institution after another, from being a supposed primary necessity of social existence, has passed into the rank of a universally stigmatised injustice and tyranny. So it has been with the distinctions of slaves and freemen, nobles and serfs, patricians and plebeians; and so it will be, and in part already is, with the aristocracies of colour, race, and sex.”

The second passage comes from the very end of Mill’s Utilitarianism. Marx talked about laws of historical development; Mill in his earliest writings –”Perfectibility,” “Civilization,” “The Spirit of the Age” – talks about “tendencies” (i.e., the spirit).

What is the goal of History to Marx and Mill? Essentially an egalitarian world, a world without polarizing impulses which divide people, and which create hierarchy. History, as it unfolds itself, eliminates hierarchy and leaves “no one behind,” as we say in America.

First, how does such a proposition of a non-hierarchical order of things sound to an eminent historian like yourself? Second, given the “equality” of results—that is, the fact that liberalism is turning into soft totalitarianism—should one see the progressive vision of history as the source of oppressiveness of the two socio-political systems?

JB: To be succinct, equality of outcome, as an impossible result, can only be the objective of the misguided and/or totalitarian. That encompasses liberalism and Marxism, both of which are based on the flawed proposition that mankind must be made equal, and that all else is a false reaction and/or consciousness. Thus, the false consciousness that the Left propounds is in fact its condition.

ZJ: A typical liberal response to your answer about equality of outcome is: we want equality of opportunity. When I hear it, I tell my students: “do farmers in all places have the same opportunity, the same fertile soil and good climate? The same goes for fishermen, and so on.” My second response is: “consider your situation: you have equal opportunity in my class to learn from me; do all of you take the advantage of it? The majority of you did not even do the reading for today.” Some of them seem to understand what I am saying; others resist it. How do you respond to it?

JB: I agree entirely with your observations about teaching. Moreover, the pursuit of equality only creates more inequalities, not only in the determination of an alleged problem, but also in the measures pursued by means of implementation and with reference to the likely outcomes. As a consequence, we are in the world of fleas on fleas.

More subtly, the quest to end inequality inevitably destabilises the precarious equality between state and society, and between government and the individual.

ZJ: Let me put forth a suggestion here, and please do not hesitate to correct me if I am wrong. England is not exactly a home of Liberalism. True, we can talk about the project of broadening the franchise through the Reform Bills of 1832, 1867, and 1884–85. But they can be said to be fundamentally democratic claims. Yet Mill’s Liberalism, as a panoramic, all-embracing vision in the context of 19th century English political thought, occupies a rather exceptional place. Mill’s ideology, because that is what his system is, inscribes itself better in the Continental way of thinking.

Could one say that Liberalism came to England through the back door, through France? I do not mean by that a commonsensical claim, which says that we all are influenced by ideas which come from different geographical places. But that Mill created a political philosophy that had little chance of being created out of “natural” English soil? One could literally point with a finger to places in his On Liberty which Mill “borrowed” from Guizot, in whose General History of Civilization in Europe he found a progressive scheme of history, as much as he borrowed from Wilhelm von Humboldt and Alexis de Tocqueville.

JB: English political thought and practice are traditionally accretional, with the ad hoc quality owing much both to the specific nature of case law and to its use in a parliamentary context on a contingent basis arising from particular challenges. As a result, Mill’s systematic prospectus prefigured the challenge of the later stages of the EU in providing an account that left no real role for the granulated character of English life and institutions: An excess of philosophical idealism cut across the organic development of the nation.

ZJ: You call yourself conservative. Can you explain what it means to you today?

JB: Change in the form of adaptation is an obvious necessity of the human species, but a conservative knows that in itself change is not a moral good, and that change ought to be referential to the past and reverential of it. The social and psychological benefit of continuity is as one with an ideological commitment to the value and values of the past. That is not reaction, but a key element of the trust between the generations that is a necessity for us as individuals and as part of a broader group.

ZJ: You wrote 140 books, including the history of the world, which means you know more history than any single individual on the planet. Historians by the very nature of their profession should care about the Past. Many of your colleagues seem to use history to invalidate Tradition, Culture, the Past—History. How do you explain their attitude? Is it the hatred of oneself—mankind—as Herr Freud would have it? But to be serious: could we say that they are unhappy about who we, as human beings, are?

JB: I fear we are looking here at a profession which is disproportionately attached to identity politics of a peculiarly destructive form, in large part because of a combination of facile Post-Modernism with doctrinaire Socialism. Existing systems are rubbished in terms of an alleged false consciousness.

ZJ: The Walters Museum in Baltimore, where I live, announced (proudly) that this year they will not purchase any pieces of European art; only the art by minorities. They are looking for funds to by art created by “minority” cultures. Decisions like that could be considered insane, but they are made by people in charge of serious cultural institutions.

Looking from a broad historical perspective, one could say, there is nothing surprising in it; the Americans are repudiating, and disposing of, the Past, they continue the 1776 Rebellion. In the middle 1980s they started repudiating education by doing away of what used to be called in the US Western Civilization courses, or Great Books programs; 35 years later we see the intellectual devastation not just in the educational realm but public realm. American students do not know anything. Compare them to students from Kenya, Nigeria, Nepal, Pakistan, India and other places…

Once again, the comparison with Communism comes to mind. They too, were selling “the bourgeois” art in the 1930s. American museums are full of the paintings the Hermitage sold, including a great Poussin in Philadelphia.

JB: Yes, see also the sales by the Newark Museum. The destruction of a great heritage is serving fashionable interests deploying an anti-colonial agenda, so-called, in order to justify their sectional and partisan political agenda. It has no intellectual purpose, but is a deliberately iconoclastic movement which delights in disorientating culture and society

ZJ: Here is a sentence from a recent email by my former (female) student: “I had told you once: We are all on the same conveyor belt headed to the slaughterhouse, just some are further down than others. I’m just trying to save my soul.”

First, what I see in her email is a sense of desperation—the same sense of desperation that people under communism felt—the Roller of History will crush us, thus we need to “adjust our thinking to the official views.” It explains why so many intellectuals compromised, sold themselves, their intellect, talent, integrity… to the ideological devil. More importantly, my student’s reaction is emblematic of how the young and thoughtful American feels.

I used quotations from Marx and Mill to make a point. What is the goal of History to them? An egalitarian world, a world without polarizing impulses which divide people, and which create hierarchy. History eliminates hierarchy and leaves “no one behind,” as we say in America.

JB: The presentation of history as uni-totalitarian is morally flawed and empirically wrong. It is a present, not conceit that seeks to extol a particular perception at the expense of the complexity of the past and the role of free will and choice, both moral and otherwise. The idea of determinism underlies such teleological visions, but they empty life of choice and therefore moral compass.

ZJ: Thank you, Professor Black.

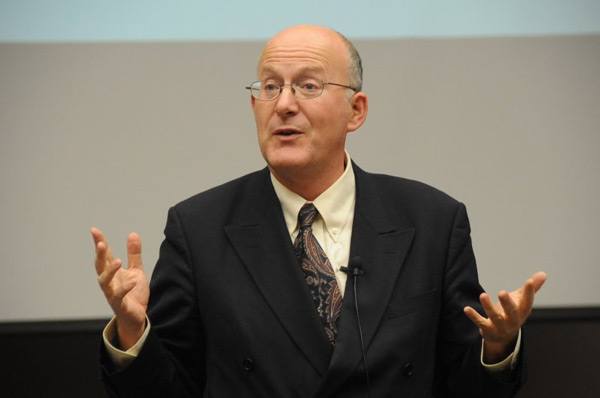

The image shows Captain Ewart capturing the eagle standard of the French 45th Regiment, at the Battle of Waterloo, by Denis Dighton, painted 1815-1817.

This interview was prepared for the Polish magazine Arcana and appears with permission.