Factum est hoc proelium in die XIIII mensis Maii anno MCCLXIIII.

[MS. Harley 978. fol. 128, r].

Calamus velociter scribe sic scribentis,

Lingua laudabiliter te benedicentis,

Dei patris dextera, domine virtutum,

Qui das tuis prospera quando vis ad nutum;

In te jam confidere discant universi,

Quos volebant perdere qui nunc sunt dispersi.

Quorum caput capitur, membra captivantur;

Gens elata labitur, fideles lætantur.

Jam respirat Anglia, sperans libertatem;

Cuï Dei gratia det prosperitatem!

Comparati canibus Angli viluerunt,

Sed nunc victis hostibus caput extulerunt.

Gratiæ millesimo ducentesimoque

Anno sexagesimo quarto, quarta quoque

Feria Pancratii post sollempnitatem,

Valde gravis prelii tulit tempestatem

Anglorum turbatio, castroque Lewensi;

Nam furori ratio, vita cessit ensi.

Pridie qui Maii Idus confluxerunt,

Horrendi discidii bellum commiserunt;

Quod fuit Susexiæ factum comitatu,

Fuit et Cicestriæ in episcopatu.

Gladius invaluit, multi ceciderunt,

Veritas prævaluit, falsique fugerunt.

Nam perjuris restitit dominus virtutum,

Atque puris præstitit veritatis scutum.

Hos vastavit gladius foris, intus pavor;

Confortavit plenius istos cœli favor.

Victoris sollempnia sanctæque coronæ

Reddunt testimonia super hoc agone;

Cum dictos ecclesia sanctos honoravit,

Milites victoria veros coronavit.

Dei sapientia, regens totum mundum,

Fecit mirabilia bellumque jocundum;

Fortes fecit fugere, virosque virtutis

In claustro se claudere, locis quoque tutis.

Non armis sed gratia christianitatis,

Id est in ecclesia, excommunicatis

Unicum refugium restabat, relictis

Equis, hoc consilium occurrebat victis.

Et quam non timuerant prius prophanare,

Quam more debuerant matris honorare,

Ad ipsam refugiunt, licet minus digni,

Amplexus se muniunt salutaris ligni.

Quos matrem contempnere prospera fecerunt,

Vulnera cognoscere matrem compulerunt.

Apud Northamptoniam dolo prosperati,

Spreverunt ecclesiam infideles nati;

Sanctæ matris viscera ferro turbaverunt,

Prosperis non prospera bella meruerunt.

Mater tunc injuriam tulit patienter,

Quasi per incuriam, sed nec affluenter:

Punit hanc et alias quas post addiderunt,

Nam multas ecclesias insani læserunt;

Namque monasterium, quod Bellum vocatur,

Turba sævientium, quæ nunc conturbatur,

Inmisericorditer bonis spoliavit,

Atque sibi taliter bellum præparavit.

Monachi Cystercii de Ponte-Roberti

A furore gladii non fuissent certi,

Si quingentas principi marcas non dedissent.

Quas Edwardus accipi jussit, vel perissent.

Hiis atque similibus factis meruerunt

Quod cesserunt hostibus et succubuerunt.

Benedicat dominus S. de Monte-Forti!

Suis nichilominus natis et cohorti!

Qui se magnanimiter exponentes morti,

Pugnaverunt fortiter, condolentes sorti

Anglicorum flebili, qui subpeditati

Modo vix narrabili, peneque privati

Cunctis libertatibus, immo sua vita,

Sub duris principibus langüerunt ita,

Ut Israelitica plebs sub Pharaone,

Gemens sub tyrannica devastatione.

Sed hanc videns populi Deus agoniam,

Dat in fine seculi novum Mathathiam,

Et cum suis filiis zelans zelum legis,

Nec cedit injuriis nec furori regis.

Seductorem nominant .S. atque fallacem;

Facta sed examinant probantque veracem.

Dolosi deficiunt in necessitate;

Qui mortem non fugiunt, sunt in veritate.

Sed nunc dicit æmulus, et insidiator,

Cujus nequam oculus pacis perturbator:

“Si laudas constantiam, si fidelitatem,

Quæ mortis instantiam vel pœnalitatem

Non fugit, æqualiter dicentur constantes

Qui concurrunt pariter invicem pugnantes,

Pariter discrimini semet exponentes,

Duroque cognomini se subjicientes.”

Sed in nostro prelio cuï nunc instamus,

Qualis sit discretio rei videamus.

Comes paucos habuit armorum expertos

Pars regis intumuit, bellatores certos

Et majores Angliæ habens congregatos,

Floremque militiæ regni nominatos;

Qui Londoniensibus armis comparati,

Essent multis milibus trecenti prælati;

Unde contemptibiles illis extiterunt,

Et abhominabiles expertis fuerunt.

Comitis militia plurima tenella;

In armis novitia, parum novit bella.

Nunc accinctus gladio tener adolescens

Mane stat in prelio armis assuescens;

Quid mirum si timeat tyro tam novellus,

Et si lupum caveat impotens agnellus?

Sic ergo militia sunt inferiores

Qui pugnant pro Anglia, sunt et pauciores

Multo viris fortibus, de sua virtute

Satis gloriantibus, ut putarent tute,

Et sine periculo, velut absorbere

Quotquot adminiculo Comiti fuere.

Nam et quos adduxerat Comes ad certamen,

De quibus speraverat non parvum juvamen,

Plurimi perterriti mox se subtraxerunt,

Et velut attoniti fugæ se dederunt;

Et de tribus partibus tertia recessit.

Comes cum fidelibus paucis nunquam cessit.

Gedeonis prelium nostro comparemus,

In quibus fidelium vincere videmus

Paucos multos numero fidem non habentes,

Similes Lucifero de se confidentes.

“Si darem victoriam,” dicit Deus, “multis,

Stulti michi gloriam non darent, sed stultis.”

Sic si Deus fortibus vincere dedisset,

Vulgus laudem talibus non Deo dedisset.

Ex hiis potest elici quod non timuerunt

Deum viri bellici, unde nil fecerunt

Quod suam constantiam vel fidelitatem

Probet, sed superbiam et crudelitatem;

Volentes confundere partem quam spreverunt,

Exeuntes temere cito corruerunt.

Cordis exaltatio præparat ruinam,

Et humiliatio meretur divinam

Dari sibi gratiam; nam qui non confidit

De Deo, superbiam Deus hanc elidit.

Aman introducimus atque Mardocheum;

Hunc superbum legimus, hunc verum Judæum;

Lignum quod paraverat Aman Mardocheo,

Mane miser tollerat suspensus in eo.

Reginæ convivium Aman excœcavit,

Quod ut privilegium magnum reputavit;

Sed spes vana vertitur in confusionem,

Cum post mensam trahitur ad suspensionem.

Sic extrema gaudii luctus occupavit,

Cum finem convivii morti sociavit.

Longe dissimiliter accidit Judæo,

Honorat sublimiter quem rex, dante Deo.

Golias prosternitur projectu lapilli;

Quem Deus persequitur, nichil prodest illi.

Ad prædictas varias adde rationes,

Quod tot fornicarias fætidi lenones

Ad se convocaverant, usque septingentas,

Quas scire debuerant esse fraudulentas,

Sathanæ discipulas ad decipiendas

Animas, et faculas ad has incendendas,

Dolosas novaculas ad crines Samsonis

Radendos, et maculas turpis actionis

Inferentes miseris qui non sunt cordati,

Nec divini muneris gratia firmati,

Carnis desideriis animales dati,

Cujus immunditiis, brutis comparati,

Esse ne victoria digni debuerunt,

Qui carnis luxuria fœda sorduerunt:

Factis lupanaribus robur minuerunt,

Unde militaribus indigni fuerunt.

Accingitur gladio super femur miles,

Absit dissolutio, absint actus viles;

Corpus novi militis solet balneari,

Ut a factis vetitis discat emundari.

Qui de novo duxerant uxores legales,

Domini non fuerant apti bello tales,

Gedeonis prelio teste, multo minus

Quos luxus incendio læserat caminus.

Igitur adulteros cur Deus juvaret,

Et non magis pueros mundos roboraret?

Mundentur qui cupiunt vincere pugnando;

Qui culpas subjiciunt sunt in triumphando;

Primo vincant vitia, qui volunt victores

Esse cum justitia super peccatores.

Si justus ab impio quandoque videtur

Victus, e contrario victor reputetur;

Nam nec justus poterit vinci, nec iniquus

Vincere dum fuerit juris inimicus.

Æquitatem comitis Symonis audite:

Cum pars regis capitis ipsius et vitæ

Solam pœnam quæreret, nec redemptionem

Capitis admitteret, sed abscisionem,

Quo confuso plurima plebs confunderetur,

Et pars regni maxima periclitaretur,

Ruina gravissima statim sequeretur;

Quæ mora longissima non repareretur!

.S. divina gratia præsul Cycestrensis,

Alta dans suspiria pro malis immensis

Jam tunc imminentibus, sine fictione,

Persüasis partibus de formatione

Pacis, hoc a Comite responsum audivit:

“Optimos eligite, quorum fides vivit,

Qui decreta legerint, vel theologiam

Decenter docuerint sacramque sophiam,

Et qui sciant regere fidem Christianam;

Quicquidque consulere per doctrinam sanam

Quicquidve discernere tales non timebunt,

Quod dicent, suscipere promptos nos habebunt;

Ita quod perjurii notam nesciamus,

Sed ut Dei filii fidem teneamus.”

Hinc possunt perpendere facile jurantes,

Et quod jurant spernere parum dubitantes,

Quamvis jurent licita, cito recedentes,

Deoque pollicita sana non reddentes,

Quanta cura debeant suum juramentum

Servare, cum videant virum nec tormentum

Neque mortem fugere propter jusjurandum,

Præstitum non temere, sed ad reformandum

Statum qui deciderat Anglicanæ gentis,

Quem fraus violaverat hostis invidentis.

En Symon obediens spernit dampna rerum,

Pœnis se subjiciens, ne dimittat verum,

Cunctis palam prædicans factis plus quam dictis,

Quod non est communicans veritas cum fictis.

Væ perjuris miseris, qui non timent Deum!

Spe terreni muneris abnegantes eum,

Vel timore carceris, sive pœnæ levis;

Novus dux itineris docet ferre quævis

Quæ mundus intulerit propter veritatem,

Quæ perfectam poterit dare libertatem.

Nam Comes præstiterat prius juramentum,

Quod quicquid providerat zelus sapientum

Ad honoris regii reformationem,

Et erroris devii declinationem,

Partibus Oxoniæ, firmiter servaret,

Hujusque sententiæ legem non mutaret;

Sciens tam canonicas constitutiones

Atque tam catholicas ordinationes

Ad regni pacificam conservationem,

Propter quas non modicam persecutionem

Prius sustinuerat, non esse spernandas;

Et quia juraverat fortiter tenendas,

Nisi perfectissimi fidei doctores

Dicerent, quod eximi possent juratores,

Qui tale præstiterant prius jusjurandum,

Et id quod juraverant non esse curandum.

Quod cum dictus pontifex regi recitaret,

Atque fraudis artifex forsitan astaret,

Vox in altum tollitur turbæ tumidorum,

“En jam miles subitur dictis clericorum!

Viluit militia clericis subjecta!”

Sic est sapientia Comitis despecta;

Edwardusque dicitur ita respondisse,

“Pax illis præcluditur, nisi laqueis se

Collis omnes alligent, et ad suspendendum

Semet nobis obligent, vel ad detrahendum.”

Quid mirum si Comitis cor tunc moveretur,

Cum non nisi stipitis pœna pareretur?

Optulit quod debuit, sed non est auditus;

Rex mensuram respuit, salutis oblitus.

Sed ut rei docuit crastinus eventus,

Modus quem tunc noluit post non est inventus.

Comitis devotio sero deridetur,

Cujus cras congressio victrix sentietur.

Lapis hic ab hostibus diu reprobatus,

Post est parietibus duobus aptatus.

Angliæ divisio desolationis

Fuit in confinio, sed divisionis

Affuit præsidio lapis angularis,

Symonis religio sane singularis.

Fides et fidelitas Symonis solius

Fit pacis integritas Angliæ totius;

Rebelles humiliat, levat desperatos,

Regnum reconsilians, reprimens elatos.

Quos quo modo reprimit? certe non laudendo,

Sed rubrum jus exprimit dure confligendo;

Ipsum nam confligere veritas coegit,

Vel verum deserere, sed prudens elegit

Magis dare dexteram suam veritati,

Viamque per asperam junctam probitati,

Per grave compendium tumidis ingratum,

Optinere bravium violentis datum,

Quam per subterfugium Deo displicere,

Pravorumque studium fuga promovere.

Nam quidam studuerant Anglorum delere

Nomen, quos jam cæperant exosos habere,

Contra quos opposuit Deus medicinam,

Ipsorum cum noluit subitam ruinam.

Hinc alienigenas discant advocare

Angli, si per advenas volunt exulare.

Nam qui suam gloriam volunt ampliare,

Suamque memoriam vellent semper stare,

Suæ gentis plurimos sibi sociari,

Et mox inter maximos student collocare;

Itaque confusio crescit incolarum,

Crescit indignatio, crescit cor amarum,

Cum se premi sentiunt regni principales

Ab hiis qui se faciunt sibi coæquales,

Quæ sua debuerant esse subtrahentes,

Quibus consüeverant crescere, crescentes.

Eschaetis et gardiis suos honorare

Debet rex, qui variis modis se juvare

Possunt, qui quo viribus sunt valentiores,

Eo cunctis casibus sunt securiores.

Sed qui nil attulerant, si suis ditantur,

Qui nullius fuerant, si magnificantur,

Crescere cum ceperint, semper scandunt tales

Donec supplantaverint viros naturales;

Principis avertere cor a suis student,

Ut quos volunt cadere gloria denudent.

Et quis posset talia ferre patienter?

Ergo discat Anglia cavere prudenter,

Ne talis perplexitas amplius contingat,

Ne talis adversitas Anglicos inpingat.

Hüic malo studuit comes obviare,

Quod nimis invaluit quasi magnum mare,

Quod parvo conamine nequibat siccari,

Sed magno juvamine Dei transvadari.

Veniant extranei cito recessuri,

Quasi momentanei, sed non permansuri.

Una juvat aliam manuum duarum,

Neutra tollens gratiam verius earum;

Juvet et non noceat locum retinendo.

Quæque suum valeat ita veniendo;

Gallicus ad Anglicum benefaciendo.

Et non per sophisticum vultum seducendo,

Nec alter alterius bona subtrahendo;

Immo suum potius onus sustinendo.

Commodum si proprium comitem movisset,

Nec haberet alium zelum, nec quæsisset

Toto suo studio reformationi

Regni, sed intentio dominationi,

Solam suam quæreret, et promotionem

Suorum proponerat, ad ditationem

Filiorum tenderet, et communitatis

Salutem negligeret, ac duplicitatis

Palli[o] supponeret virus falsitatis;

Sic fidem relinqueret Christianitatis,

Et horrendæ subderet se pœnalitatis

Legi, nec effugeret pondus tempestatis.

Et quis potest credere quod se morti daret,

Suos vellet perdere, ut sic exaltaret?

Callide si palliant honorem venantes;

Et quod mortem fugiant semper meditantes;

Nulli magis diligunt vitam temporalem,

Nulli magis eligunt statum non mortalem.

Honores qui sitiunt simulate tendunt,

Caute sibi faciunt nomen quod intendunt;

Non sic venerabilis .S. de Monte-forti,

Qui se Christo similis dat pro multis morti;

Ysaac non moritur cum sit promptus mori;

Vervex morti traditur, Ysaac honori.

Nec fraus nec fallacia Comitem promovit,

Sed divina gratia, quæ quos juvet novit.

Horam si vocaveris locum que conflictus,

Invenire poteris quod ut esset victus

Potius quam vinceret illi conferebat;

Sed ut non succumberet Deus providebat.

Non de nocte subito surripit latenter;

Immo die redito pugnat evidenter.

Sic et locus hostibus fuit oportunus,

Ut hinc constet omnibus esse Dei munus,

Quod cessit victoria de se confidenti.

Hinc discat militia, quæ torneamenti

Laudat exercitium, ut sic expedita

Reddatur ad prælium, qualiter contrita

Fuit hic pars fortium exercitatorum,

Armis imbecillium et inexpertorum:

Ut confundet fortia, promovet infirmos,

Confortat debilia Deus, sternit firmos.

Sic nemo confidere de se jam præsumat;

Sed in Deum ponere spem si sciat, sumat

Arma cum constantia, nichil dubitando,

Cum sit pro justitia Deus adjuvando.

Sicque Deum decuit Comitem juvare,

Sine quo non potuit hostem superare.

Cujus hostem dixerim? Comitis solius?

Vel Anglorum sciverim regnique totius?

Forsan et ecclesiæ, igitur et Dei?

Quod si sic, quid gratiæ; conveniret ei?

Gratiam demeruit in se confidendo,

Nec juvari debuit Deum non timendo.

Cadit ergo gloria propriæ virtutis;

Et sic in memoria, qui dat destitutis

Viribus auxilium, paucis contra multos,

Virtute fidelium conterendo stultos,

Benedictus dominus Deus ultionum!

Qui in cœlis eminus sedet super thronum,

Et virtute propria colla superborum

Calcat, subdens grandia pedibus minorum.

Duos reges subdidit et hæredes regum,

Quos captivos reddidit transgressores legum,

Pompamque militiæ cum magna sequela

Dedit ignominiæ; nam barones tela

Quæ zelo justitiæ pro regno sumpserunt,

Filiis superbiæ communicaverunt,

Usque dum victoria de cœlo dabatur,

Cum ingenti gloria quæ non sperabatur,

Arcus namque fortium tunc est superatus,

Cœtus inbecillium robore firmatus;

Et de cœlo diximus, ne quis glorietur;

Sed Christo quem credimus omnis honor detur!

Christus enim imperat, vincit, regnat idem;

Christus suos liberat, quibus dedit fidem.

Ne victorum animus manus osculetur

Suas, Deum petimus quod illis præstetur;

Et quod Paulus suggerit ab ipsis servetur,

“Qui lætatus fuerit, in Deo lætetur.”

Si quis nostrum gaudeat vane gloriatus,

Dominus indulgeat, et non sit iratus!

Et cautos efficiat nostros in futurum;

Ne factum deficiat, faciant se murum!

Quod cæpit perficiat vis omnipotentis,

Regnumque reficiat Anglicanæ gentis!

Ut sit sibi gloria, suis pax electis,

Donec sint in patria se duce provectis.

Hæc Angli de prælio legite Lewensi,

Cujus patrocinio vivitis defensi;

Quia si victoria jam victis cessisset,

Anglorum memoria victa viluisset.

Cuï comparabitur nobilis Edwardus?

Forte nominabitur recte leopardus.

Si nomen dividimus, leo fit et pardus:

Leo, quia vidimus quod non fuit tardus

Aggredi fortissima, nullius occursum

Timens, audacissima virtute discursum

Inter castra faciens, et velut ad votum

Ubi et proficiens, ac si mundum totum

Alexandro similis cito subjugaret

Si fortunæ mobilis rota semper staret;

In qua summus protinus sciat se casurum,

Qui regnat ut dominus parum regnaturum.

Quod Edwardo nobili liquet accidisse,

Quem gradu non stabili constat cecidisse.

Leo per superbiam, per ferocitatem;

Est per inconstantiam et varietatem

Pardus, verbum varians et promissionem,

Per placentem pallians se locutionem.

Cum in arcto fuerit quicquid vis promittit;

Sed mox ut evaserit, promissum dimittit.

Testis sit Glovernia, ubi quod juravit

Liber ab angustia statim revocavit.

Dolum seu fallaciam quibus expeditur

Nominat prudentiam; via qua venitur

Quo vult quamvis devia recta reputatur;

Nefas det placentia, fasque nominatur;

Quicquid libet licitum dicit, et a lege

Se putat explicitum, quasi major rege.

Nam rex omnis regitur legibus quas legit;

Rex Saül repellitur, quia leges fregit;

Et punitus legitur David mox ut egit

Contra legem; igitur hinc sciat qui legit,

Quod non potest regere qui non servat legem;

Nec hunc debent facere ad quos spectat regem.

O Edwarde! fieri vis rex, sine lege;

Vere forent miseri recti tali rege!

Nam quid lege rectius qua cuncta reguntur,

Et quid jure verius quo res discernuntur?

Si regnum desideras, leges venerare;

Vias dabit asperas leges impugnare,

Asperas et invias quæ te non perducent;

Leges si custodias ut lucerna lucent.

Ergo dolum caveas et abomineris;

Veritati studeas, falsum detesteris.

Quamvis dolus floreat, fructus nequit ferre;

Hoc te psalmus doceat; ad fideles terræ

Dicit Deus, “Oculi mei sunt, sedere

Quos in fine seculi mecum volo vere.”

Dolus Northamptoniæ vide quid nunc valet;

Nec fervor fallaciæ velut ignis calet.

Si dolum volueris igni comparare,

Paleas studueris igni tali dare,

Quæ mox, ut exarserint, desistunt ardere,

Et cum vix inceperint terminum tenere.

Ita transit vanitas non habens radices;

Radicata veritas non mutat per vices.

Ergo tibi libeat id solum quod licet,

Et non tibi placeat quod vir duplex dicet.

Princeps quæ sunt principe digna cogitabit:

Ergo legem suscipe, quæ te dignum dabit

Multorum regimine, dignum principatu,

Multorum juvamine, multo comitatu.

Et quare non diligis quorum rex vis esse?

Prodesse non eligis, sed tantum præesse.

Qui nullius gloriam nisi suam quærit,

Ejus per superbiam quicquid regit, perit.

Ita totum periit nuper quod regebas;

Gloria præteriit quam solam quærebas;

En radicem tangimus perturbationis

Regni de quo scribimus, et dissentionis

Partium quæ prælium dictum commiserunt.

Ad diversa studium suum converterunt.

Rex cum suis voluit ita liber esse;

Et sic esse debuit, fuitque necesse

Aut esse desineret rex, privatus jure

Regis, nisi faceret quicquid vellet; curæ

Non esse magnatibus regni, quos præferret

Suis comitatibus, vel quibus conferret

Castrorum custodiam, vel quem exhibere

Populo justitiam vellet, et habere

Regni cancellarium thesaurariumque.

Suum ad arbitrium voluit quemcumque,

Et consiliarios de quacumque gente,

Et ministros varios se præcipiente,

Non intromittentibus se de factis regis

Angliæ baronibus, vim habente legis

Principis imperio, et quod imperaret

Suomet arbitrio singulos ligaret.

Nam et comes quilibet sic est compos sui,

Dans suorum quidlibet quantum vult et cuï

Castra, terras, redditus, cuï vult committit,

Et quamvis sit subditus, rex totum permittit.

Quod si bene fecerit, prodest facienti;

Si non, ipse viderit, sibimet nocenti

Rex non adversabitur. Cur conditionis

Pejoris efficitur princeps, si baronis,

Militis, et liberi res ita tractantur?

Quare regem fieri servum machinantur,

Qui suam minuere volunt potestatem,

Principis adimere suam dignitatem,

Volunt in custodiam et subjectionem

Regiam potentiam per seditionem

Captivam retrudere, et exhæredare

Regem, ne tam ubere valeat regnare

Sicut reges hactenus qui se præcesserunt,

Qui suis nullatenus subjecti fuerunt,

Sed suas ad libitum res distribuerunt,

Et ad suum placitum sua contulerunt.

Hæc est regis ratio, quæ vera videtur,

Et hæc allegatio jus regni tuetur.

Sed nunc ad oppositum calamus vertatur:—

Baronum propositum dictis subjungatur;

Et auditis partibus dicta conferantur,

Atque certis finibus collata claudantur,

Ut quæ pars sit verior valeat liquere.

Veriori promor populus parere.

Baronum pars igitur jam pro se loquatur,

Et quo zelo ducitur rite prosequatur.

Quæ pars in principio palam protestatur,

Quod honori regio nichil machinatur;

Vel quærit contrarium, immo reformare

Studet statum regium et magnificare;

Sicut si ab hostibus regnum vastaretur,

Non sine baronibus tune reformaretur,

Quibus hoc competeret atque conveniret;

Et qui tunc se fingeret, ipsum lex puniret

Ut reum perjurii, regis proditorem,

Qui quicquid auxilii regis ad honorem

Potest, debet domino cum periclitatur,

Cum velut in termino regnum deformatur.

Regis adversarii sunt hostes bellantes,

Et consiliarii regi adulantes,

Qui verbis fallacibus principem seducunt,

Linguisque duplicibus in errorem ducunt:

Hii sunt adversarii perversis pejores;

Hii se bonos faciunt cum sint seductores,

Et honoris proprii sunt procuratores;

Incautos decipiunt, quos securiores

Reddunt per placentia, unde non caventur,

Sed velut utilia dicentes censentur.

Hii possunt decipere plusquam manifesti,

Qui se sciunt fingere velut non infesti.

Quid si tales miseri, talesque mendaces,

Adhærerent lateri principis, capaces

Totius malitiæ, fraudis, falsitatis,

Stimulis invidiæ puncti, pravitatis

Facinus exquirerent, per quod regni jura

Ad suas inflecterent pompas, quæque dura

Argumenta fingerent, quæ communitatem

Paulatim confunderent, universitatem

Populi contererent et depauperarent,

Regnumque subverterent et infatuarent,

Quod nullus justitiam posset optinere,

Nisi qui superbiam talium fovere

Vellet, per pecuniam largiter collatam;

Quis tantam injuriam sustineret ratam?

Et si tales studiis suis immutarent

Regnum, ut injuriis jura supplantarent;

Calcatis indigenis advenas vocarent;

Et alienigenis regnum subjugarent:

Magnates et nobiles terne non curarent,

Atque contemptibiles in summo locarent;

Et magnos dejicerent et humiliarent;

Ordinem perverterent et præposterarent;

Optima relinquerent, pessimis instarent;

Nonne qui sic facerent regnum devastarent?

Quamvis armis bellicis foris non pugnarent,

Tamen diabolicis armis dimicarent,

Et regni flebiliter statum violarent;

Quamvis dissimiliter, non minus dampnarent.

Sive rex consentiens per seductionem,

Talem non percipiens circumventionem,

Approbaret talia regni destructiva;

Seu rex ex malitia faceret nociva,

Proponendo legibus suam potestatem,

Abutendo viribus propter facultatem;

Sive sic vel aliter regnum vastaretur,

Aut regnum finaliter destitueretur,

Tunc regni magnatibus cura deberetur,

Ut cunctis erroribus terra purgaretur.

Quibus si purgatio convenit errorum,

Convenit provisio gubernatrix morum,

Qualiter prospicere sibi non liceret,

Ne malum contingere posset quod noceret?

Quod postquam contigerit debent amovere,

Subitum ne faciat incautos dolere.

Sic quod non eveniat quicquam prædictorum,

Quod pacis impediat vel bonorum morum

Formam, sed inveniat zelus peritorum

Quod magis expediat commodo multorum;

Cur melioratio non admitteretur,

Cuï vitiatio nulla commiscetur?

Nam regis clementia regis et majestas

Approbare studia debet, quæ molestas

Leges ita temperant quod sunt mitiores,

Et dum minus onerant Deo gratiores.

Non enim oppressio plebis Deo placet,

Immo miseratio qua plebs Deo vacet.

Phara[o] qui populum Dei sic afflixit,

Quod vix ad oraculum Moysi quod dixit

Poterant attendere, post est sic punitus,

Israel dimittere cogitur invitus;

Et qui comprehendere credidit dimissum,

Mersus est dum currere putat per abyssum.

Salomon conterere Israel nolebat,

Nec ullum de genere servire cogebat;

Quia Dei populum scivit quem regebat,

Et Dei signaculum lædere timebat;

Et plusquam judicium laudat misereri,

Et plusquam supplicium pacem patri[s] veri.

Cum constat baronibus hæc cuncta licere,

Restat rationibus regis respondere.

Amotis custodibus vult rex liber esse,

Subdique minoribus non vult sed præesse;

Imperare subditis et non imperari;

Sibi nec præpositis vult humiliari.

Non enim præpositi regi præponuntur;

Immo magis incliti qui jus supponuntur.

Unius rex aliter unicus non esset,

Sed regnarent pariter quibus rex subesset.

Et hoc inconveniens quod tantum videtur,

Sit Deus subveniens, facile solvetur.

Deum namque credimus velle veritatem,

Per quem sic dissolvimus hanc dubietatem.

Unus solus dicitur et est rex revera,

Per quem mundus regitur majestate mera;

Non egens auxilio quo possit regnare,

Sed neque consilio qui nequit errare.

Ergo potens omnia sciensque præcedit

Infinita gloria omnes quibus dedit

Sub se suos regere quasique regnare,

Qui possunt deficere, possunt et errare,

Et qui suis viribus nequeunt præstare,

Suisque virtutibus hostes expugnare,

Neque sensu proprio regna gubernare,

Sed erroris invio male deviare.

Indigent auxilio sibi suffragante,

Necnon et consilio se rectificante.

Dicit rex: “Consentio tuæ rationi;

Sed horum electio subsit optioni

Meæ; quos voluero michi sociabo,

Quorum patrocinio cuncta gubernabo;

Et si mei fuerint insufficientes,

Sensum non habuerint, aut non sint potentes,

Aut si sint malevoli, et non sint fideles,

Sed sint forte subdoli, volo quod reveles

Cur ad certas debeam personas arctari,

A quibus prævaleam melius juvari?”

Cujus rei ratio cito declaratur,

Si quæ sit arctatio regis attendatur;

Non omnis arctatio privat libertatem,

Nec omnis districtio tollit potestatem.

Potestatem liberam volunt principantes,

Servitutem miseram nolunt dominantes.

Ad quid vult libera lex reges arctari?

Ne possint adultera lege maculari.

Et hæc coarctatio non est servitutis,

Sed est ampliatio regiæ virtutis.

Sic servatur parvulus regis ne lædatur;

Non fit tamen servulus quando sic arctatur.

Sed et sic angelici spiritus arctantur.

Qui quod apostatici non sint confirmantur.

Nam quod Auctor omnium non potest errare,

Omnium principium non potest peccare,

Non est inpotentia, sed summa potestas,

Magna Dei gloria magnaque majestas.

Sic qui potest cadere, si custodiatur

Ne cadat, quod libere vivat, adjuvatur

A tali custodia, nec est servitutis

Talis sustinentia, sed tutrix virtutis.

Ergo regi libeat omne quod est bonum,

Sed malum non audeat; hoc est Dei donum.

Qui regem custodiunt ne peccet temptatus,

Ipsi regi serviunt, quibus esse gratus

Sit, quod ipsum liberant ne sit servus factus,

Quod ipsum non superant a quibus est tractus.

Sed quis vere fuerit rex, est liber vere

Si se recte rexerit regnumque; licere

Sibi sciat omnia quæ regno regendo

Sunt convenientia, sed non destruendo.

Aliud est regere quod incumbit regi;

Aliud destruere resistendo legi.

A ligando dicitur lex, quæ libertatis

Tam perfecte legitur qua servitur gratis.

Omnis rex intelligat quod est servus Dei:

Illud tantum diligat quod est placens ei;

Et illius gloriam quærat in regendo,

Non suam superbiam pares contempnendo.

Rex qui regnum subditum sibi vult parere,

Reddat Deo debitum alioquin vere;

Sciat quod obsequium sibi non debetur,

Qui negat servitium quo Deo tenetur.

Rursum sciat populum non suum sed Dei,

Et ut adminiculum suum prosit ei:

Et qui parvo tempore populo præfertur,

Cito clausus marmore terræ subinfertur.

In illos se faciat ut unum ex illis;

Saltantem respiciat David cum ancillis.

Regi David similis utinam succedat,

Vir prudens et humilis qui suos non lædat;

Certe qui non læderet populum subjectum,

Sed illis impenderet amoris affectum,

Et ipsius quæreret salutis profectum,

Ipsum non permitteret plebs pati defectum.

Durum est diligere se non diligentem;

Durum non despicere se despicientem;

Durum non resistere se destituenti;

Convenit applaudere se suscipienti.

Principis conterere non est, sed tueri;

Principis obprimere non est, sed mereri

Multis beneficiis suorum favorem,

Sicut Christus gratiis omnium amorem.

Si princeps amaverit, debet reamari;

Si recte regnaverit, debet honorari;

Si princeps erraverit, debet revocari

Ab hiis quos gravaverit injuste negari,

Nisi velit corrigi; si vult emendari,

Debet ab hiis erigi simul et juvari.

Istam princeps teneat regulam regnandi,

Ut opus non habeat non suos vocandi:

Qui confundunt subditos principes ignari,

Sentient indomitos sic nolle domari.

Si princeps putaverit universitate

Quod solus habuerit plus de veritate,

Et plus de scientia, plus cognitionis,

Plus abundet gratia, plusque Dei donis:

Si non sit præsumptio, immo sit revera,

Sua tune instructio suorum sincera

Subditorum lumine corda perlustrabit;

Et cum moderamine suos informabit.

Moysen proponimus, David, Samuelem,

Quorum quemque novimus principem fidelem;

Qui a suis subditis multa pertulerunt,

Nec tamen pro meritis illos abjecerunt,

Nec illis extraneos superposuerunt,

Sed rexerunt per eos qui sui fuerunt.

“Ego te præficiam populo majori,

Et hunc interficiam;” dicit Deus.—“Mori

Malo, quam hic pereat populus,” benignus

Moyses respondeat, principatu dignus.

Sicque princeps sapiens nunquam reprobabit

Suos, sed insipiens regnum conturbabit.

Unde si rex sapiat minus quam deberet;

Quid regno conveniat regendo? num quæret

Suo sensu proprio quibus fulciatur,

Quibus diminutio sua suppleatur?

Si solus elegerit, facile falletur,

Utilis qui fuerit a quo nescietur.

Igitur communitas regni consulatur;

Et quid universitas sentiat, sciatur,

Cuï leges propriæ maxime sunt notæ.

Nec cuncti provinciæ sic sunt idiotæ,

Quin sciant plus cæteris regni sui mores,

Quos relinquunt posteris hii qui sunt priores.

Qui reguntur legibus magis ipsas sciunt;

Quorum sunt in usibus plus periti fiunt;

Et quia res agitur sua, plus curabunt,

Et quo pax adquiritur sibi procurabunt.

Pauca scire poterunt qui non sunt experti;

Parum regno proderunt, nisi qui sunt certi.

Ex hiis potest colligi quod communitatem

Tangit quales eligi ad utilitatem

Regni recte debeant; qui velint et sciant

Et prodesse valeant, tales regis fiant

Et consiliarii et coadjutores;

Quibus noti varii patriæ sunt mores;

Qui se lædi sentiunt, si regnum lædatur;

Regnumque custodiunt, ne, si noceatur

Toti, partes doleant simul patientes;

Gaudenti congaudeant, si sint diligentes.

Nobile juditium regis Salomonis

Ponamus in medium; quæ divisionis

Parvuli non horruit inhumanitatem,

Quia non condoluit atque pietatem

Maternam non habuit, quod mater non erat

Teste rege docuit; ergo tales quærat

Princeps, qui condoleant universitati,

Qui materne timeant regnum dura pati.

Sed si quem non moveat ruina multorum;

Si solus optineat quæ vult placitorum;

Multorum regimini non est coaptatus,

Suo cum sit omnium soli totus datus.

Communis conveniens est communitati;

Sed vir incompatiens cordis indurati

Non curat si veniant multis casus duri;

Casibus non obviant tales modo muri.

Igitur eligere si rex per se nescit

Qui sibi consulere sciant, hinc patescit

Quid tunc debet fieri. Nam communitatis

Est ne fiant miseri duces dignitatis

Regiæ, sed optimi et electi viri,

Atque probatissimi qui possint inquiri.

Nam cum gubernatio regni sit cunctorum

Salus vel perditio, multum refert quorum

Sit regni custodia; sicut est in navi;

Confunduntur omnia si præsint ignavi;

Si quis transfretantium positus in navi

Ad se pertinentium abutatur clavi,

Non refert si prospere navis gubernetur.

Sic qui regnum regere debent, cura detur

Si de regno quispiam non recte se regit;

Viam vadit inviam quam forsan elegit.

Optime res agitur universitatis,

Si regnum dirigitur via veritatis.

Et tamen si subditi sua dissipare

Studeant, præpositi possunt refrenare

Suorum stultitiam et temeritatem,

Ne per insolentiam vel fatuitatem

Stultorum potentia regni subnervetur,

Hostibus audacia contra regnum detur.

Nam quocumque corporis membro violato,

Fit minoris roboris corpus. Ita dato

Quod vel viri liceat propriis abuti,

Quamvis regno noceat; plures mox secuti

Et libertatem noxiam, sic multiplicabunt

Erroris insaniam, quod totum dampnabunt.

Nec libertas proprie debet nominari,

Quæ permittit inscie stultos dominari;

Sed libertas finibus juris limitetur,

Spretisque limitibus error reputetur.

Alioquin liberum dices furiosum,

Quamvis omne prosperum illi sit exosum.

Ergo regis ratio de suis subjectis,

Suomet arbitrio quorum volunt vectis,

Per hoc satis solvitur, satis infirmatur;

Dum quivis qui subditur majore domatur.

Quia nulli hominum dicemus licere

Quicquid vult, sed dominum quemlibet habere

Qui errantem corrigat, benefacientem

Adjuvat, et erigit quandoque cadentem.

Præmio præferimus universitatem;

Legem quoque dicimus regis dignitatem

Regere; nam credimus esse legem lucem,

Sine qua concludimus deviare ducem.

Lex qua mundus regitur atque regna mundi

Ignea describitur; quod sensus profundi

Continet mysterium, lucet, urit, calet;

Lucens vetat devium, contra frigus valet,

Purgat et incinerat quædam, dura mollit,

Et quod crudum fuerat ignis coquit, tollit

Torporem, et alia multa facit bona.

Sancta lex similia p’rat (?) regi dona.

Istam sapientiam Salomon petivit;

Ejus amicitiam tota vi quæsivit.860

Si rex hac caruerit lege, deviabit;

Si hanc non tenuerit, turpiter errabit;

Istius præsentia recte dat regnare,

Et ejus absentia regnum perturbare.

Ista lex sic loquitur, “per me regnant reges;

Per me jus ostenditur hiis qui condunt leges.”

Istam legem stabilem nullus rex mutabit;

Sed se variabilem per istam firmabit.

Si conformis fuerit huïc legi, stabit;

Et si disconvenerit isti, vacillabit.

Dicitur vulgariter, “ut rex vult, lex vadit:”

Veritas vult aliter, nam lex stat, rex cadit.

Veritas et caritas zelusque salutis

Legis est integritas, regimen virtutis;

Veritas, lux, caritas, calor, urit zelus;

Hæc legis varietas tollit omne scelus.

Quicquid rex statuerit, consonum sit istis;

Nam si secus fecerit, plebs reddetur tristis;

Confundetur populus, si vel veritate

Caret regis oculus, sive caritate

Principis cor careat, vel severitate

Zelum non adimpleat semper moderate.

Hiis tribus suppositis, quicquid placet regi

Fiat; sed oppositis, rex resistit legi.

Sed recalcitratio stimulo non nocet;

Pauli sic instructio de cœlo nos docet.

Sic exhæredatio nulla fiet regi,

Si fiat provisio concors justæ legi.

Nam dissimulatio legem non mutabit,

Cujus firma ratio sine fine stabit.

Unde si quid utile diu est dilatum,

Irreprehensibile sit sero perlatum.

Et rex nihil proprium præferat communi;

Quia salus omnium sibi cessit uni.

Non enim præponitur sibimet victurus;

Sed ut hic qui subditur populus securus.

Reges esse noveris nomen relativum;

Nomen quoque sciveris esse protectivum;

Unde sibi vivere soli non licebat,

Qui multos protegere vivendo delebat.

Qui vult sibi vivere, non debet præesse,

Sed seorsum degere, et ut solus esse.

Principis est gloria plurimos salvare;

Cum sua molestia multos relevare.

Non alleget igitur suimet profectum,

Sed in quibus creditur subditis prospectum.

Si regnum salvaverit, quod est regis fecit;

Quicquid secus egerit in ipso defecit.

Vera regis ratio ex hiis satis patet;

Quod vacantem proprio status regis latet.

Namque vera caritas est proprietati

Quasi contrarietas, et communitati

Fœdus insolubile, conflans velut ignis

Omne quod est habile, sicut fit in lignis

Quæ dant igni crescere patiens activo,

Subtracta decrescere modo recitivo.

Ergo si fervuerit princeps caritate,

Quantumcumque poterit de communitate,

Si sollicitabitur quod recte regatur,

Et nunquam lætabitur si destituatur,

Unde si dilexerit rex regni magnates,

Quamvis solus sciverit, quasi magnus vates,

Quicquid opus fuerit ad regnum regendum,

Quicquid se decuerit, quicquid faciendum,

Quod sane decreverit illis non celabit,

Præter quos non poterit id quod ordinabit

Ad effectum ducere; igitur tractabit

Cum suis, quæ facere per se [non] putabit.

Cur sua consilia non communicabit,

A quibus auxilia supplex postulabit?

Quicquid suos allicit ad benignitatem,

Et amicos efficit, fovet unitatem,

Regiam prudentiam decet indicare

Hiis qui suam gloriam possunt augmentare.

Dominus discipulis cuncta patefecit,

Dividens a servulis quos amicos fecit;

Atque quasi nescius a suis quæsivit

Quid sentirent sæpius, quod profecte scivit.

O! si Dei quærerent principes honorem,

Regna recte regerent, et præter errorem.

Si Dei notitiam principes haberent,

Omnibus justitiam suam exhiberent.

Ignorantes dominum, velut excæcati,

Quærunt laudes hominum, vanis delectati.

Qui se nescit regere, multos male reget;

Si quis vult inspicere Psalmos, idem leget.

Joseph ut se debuit principes docere,

Propter quod rex voluit ipsum præminere.

Et in innocentia cordis sui David,

Et intelligentia, Israelem pavit.

Ex prædictis omnibus poterit liquere,

Quod regem magnatibus incumbit videre

Quæ regni conveniant gubernationi,

Et pacis expediant conservationi;

Et quod rex indigenas sibi laterales

Habeat, non advenas, neque speciales,

Vel consiliarios vel regni majores,

Qui supplantant alios atque bonos mores.

Nam talis discordia paci novercatur,

Et inducit prælia, dolos machinatur.

Nam sicut invidia diaboli mortem

Induxit, sic odia separat cohortem.

Incolas in ordine suo rex tenebit,

Et hoc moderamine regnando gaudebit.

Si vero studuerit suos degradare,

Ordinem perverterit, frustra quæret quare

Sibi non obtemperant ita perturbati;

Immo si sic facerent essent insensati.

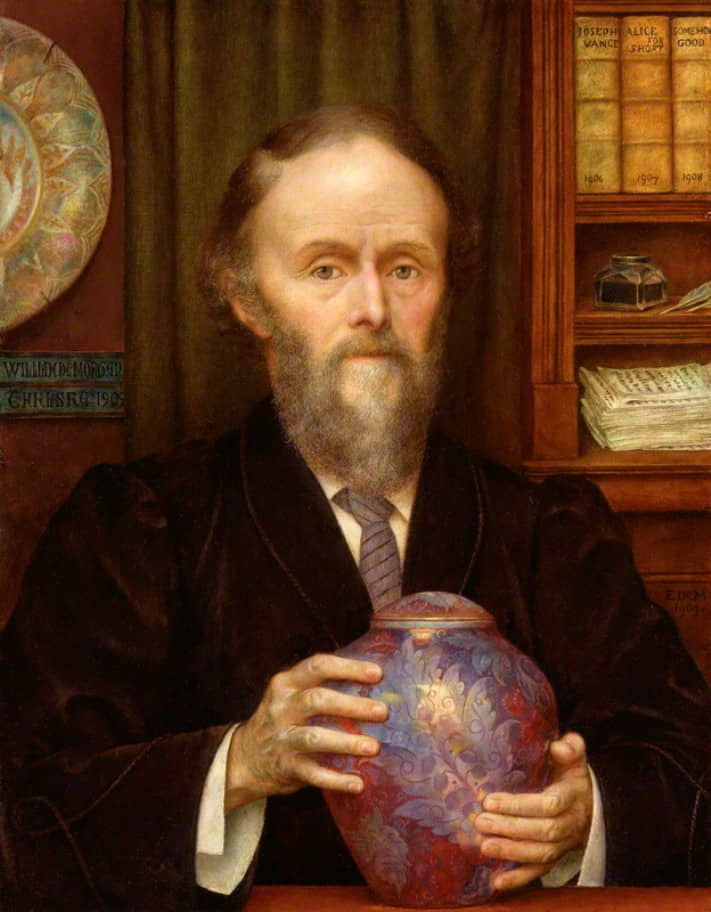

Featured: Simon de Montfort, Sixth Earl of Leicester; drawing of a stained glass window at Chartres Cathedral, ca. 1250.