Brexit has had a major impact on London’s policy making, prompting the United Kingdom to seek an autonomous and separate path from that of Brussels. This has what some call neo-imperialistic consequences, such as the return of the “East of Suez” and a renewed “Global Britan” (reminiscent of former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s initiatives); now Britain looks to new ties in Africa, Latin America and, especially, Asia.

In mid-December, Foreign Minister James Cleverly met the press and laid out the future programs of British foreign policy, which it needs to have, given the major economic, commercial and military repercussions of Brexit. Latent in British politics even when London was part of the EU, and now that Britian is out, London has promoted a “Global Britain” policy, especially a particular lean towards the Asia-Pacific region.

Cleverly acknowledged that British diplomacy has at times been slow to capitalize on the shift in geopolitical center of gravity “eastwards and southwards,” saying the UK will need to have policy goals for up to 20 years, in areas from trade to climate change , even if there were no immediate visible dividends at home. Countries like India, Indonesia and Brazil, with much younger demographics than the UK’s traditional allies who helped build post-World War II global institutions, will become increasingly influential, he said, and noting London will make confidence investments in countries that will shape the future of the world.”

Yet Cleverly’s address raised questions about whether he was advocating closer ties with some non-aligned countries that are the most willing to flout the rules-based international system in areas such as human rights. Getting prospective partners to uphold international law, respect human rights and diversity must take place “over decades,” he said, aiming for persuasion rather than conferences. Obviously, faithful to the historic British hostility towards Moscow, criticism of Moscow could not be omitted, even though the larger target was China, whose rise as an economic superpower in the last 50 years (especially in Asia and Africa), leads to concerns about its rapid military expansion and alleged “no strings attached” partnerships with developing countries.

But London’s new goals come as the UK backs down on one of its main “soft power” weapons, cutting international aid funds and tightening immigration controls after Brexit, despite a job deficit in some sectors due to the growing difficulties for foreign personnel.

Which “East of the Suez” for the UK?

As mentioned, “Global Britain” is an important counterpart to the foreign and defense policies for East of Suez (for which it is being structured as a chapter). Thus, the British security policy is seeing some changes in perspective, which can be read as part of the London approach

The United Kingdom, in a surprise move, has announced that it will negotiate “the exercise of sovereignty” with the government of the Republic of Mauritius, over the Chagos archipelago in the Indian Ocean. This announcement, totally unexpected, comes three years after the ICJ (International Court of Justice) had concluded that London had to decolonize those islands. This was announced on November 3rd by the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs of the British government, James Cleverly, who added on November 3rd that the start of negotiations had been agreed upon by the British and Mauritian governments, and that the two parties intended to reach an agreement early in 2023.

According to Cleverly, the agreement should serve to “resolve, on the basis of international law, all outstanding issues, including those relating to the former inhabitants of the Chagos archipelago,” adding that the agreement “will ensure the continued effective functioning of the base United Kingdom and United States joint military service to Diego Garcia,” and pledging to keep the United States and India informed.

Two outstanding issues remain in the dispute, and they are not insignificant. On the one hand, the right of return of the original populations of the archipelago; and on the other, which country should exercise sovereignty over those islands (and consequently, what activities they will undertake). The organizations of the exiled people of the Chagos have applauded the possibility of return, but remain skeptical.

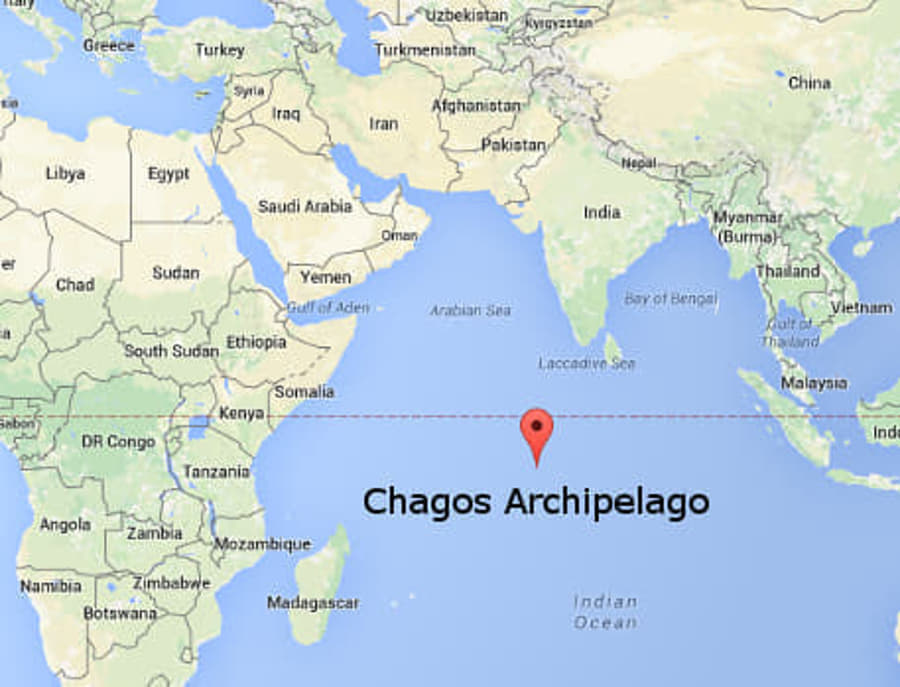

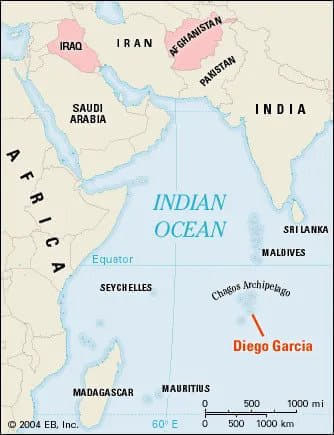

It is useful to remember that the Chagos archipelago is located in the Indian Ocean, between the Maldives (the closest country), Madagascar, the Seychelles and Somalia. It is made up of seven atolls with more than 60 islands. The largest of these is Diego Garcia, where there is a large US military base and a symbolic British presence with about 50 personnel, the Royal Naval Party 1002, which includes a small joint contingent of military police, about ten elements British Army, Royal Navy/Royal Marines, RAF, united under the acronym ROPO (Royal Overseas Police Officers).

The Chagos remained uninhabited until the end of the 18th century, when Great Britain, which controlled the archipelago, settled workers and slaves from Mozambique, Madagascar and Mauritius, forming the first permanent population. The United Kingdom administered the Chagos as part of the colony of Mauritius further south in the Indian Ocean. Since the 1950s, the possibility of establishing an air-naval base in the archipelago had begun to be evaluated, the importance of which grew with the increase in the threat of the Soviet fleet in the Indian Ocean and towards the flow of oil from the countries of the Persian Gulf towards America, Europe and Japan. It was essential to maintain a presence both in the Gulf and in the Indian Ocean.

In 1965, with the formation of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), Mauritius and the Chagos were under the administrative control of the British governor who resided in the Seychelles. In 1976, the Seychelles became independent from Great Britain and the BIOT, now reduced to the Chagos alone, was managed by the East African Desk of the Foreign Office and the representative of the crown on site was the commander of the Naval Party, but without the rank of Governor.

In January 1968, Great Britain, faced with a serious economic and financial crisis, announced its intention to withdraw its military forces from “East of Suez” by 1971 and generated a debate on the possible strategic vacuum in the Indian Ocean; and this tied in with the process of accelerated decolonization throughout the remaining British territories.

In 1965, three years before granting Mauritius independence, London separated the Chagos and set up a new administration under direct London rule. The following year, an agreement was signed with the USA for the establishment of a military base (leased until 2036).

Between 1966 and 1973, the entire population of Chagos—between 1,000 and 2,000 people, depending on the sources—was removed to prevent it from interfering with the activities of the base and relocated it to Mauritius, the United Kingdom and the Seychelles. The organizations of these populations have always denounced the relocation which they say was carried out with minimal financial compensation, very strong psychological pressure and without respecting the human rights of those people; and these organizations also claim that many of the expelled have fallen into conditions of extreme poverty. These groups are claiming the right of return, in a legal battle that has been going on for decades, so far without success, as the English courts have either ignored the appeals or rejected them. They also demand that the UK make it easier for people of Chagos origin to obtain British citizenship; and regarding Mauritius they complain that there too they are discriminated against because of their origin.

The biggest change in this situation occurred in February 2019, when the ICJ (International Court of Justice, a body responsible for adjudicating cases between states and territories), authorized by the UN General Assembly concluded that the decolonization of Mauritius in 1968 was not legally completed because the separation of the Chagos from St. Louis three years earlier “was not based on a free and genuine expression of the will of the population concerned,” because the separation violated the right of Mauritius to its territorial integrity and because, consequently, it was contrary to international law to retain British sovereignty over the Chagos. Consequently, the ICJ, albeit in an advisory opinion, has held that the United Kingdom is “obligated to terminate its administration of the Chagos archipelago as soon as possible,” and has called on member states to “work with the United Nations to complete the decolonization of Mauritius.”

For three years, London rejected the advisory opinion, stating that it would not transfer control of the Chagos to Mauritius as long as the archipelago was necessary for the defense policy of the United Kingdom (and its American ally), but that it declared itself open to dialogue. The story, beyond a vague idea of returning to “East of Suez,” represents the difficulties of London’s post-Brexit security policy (foreign and defence), so much so that India itself joined in support of Mauritius, with the clear intention of replacing the USA, as part of its policy of controlling any Chinese expansion and blocking the “string of pearls” (as the bases are called by India) that China is trying to establish around the Indian peninsula.

Meanwhile, Washington received an important offer: if London transferred sovereignty over the Chagos, the Mauritian government would be willing to lease the Diego Garcia base to the United States for another 99 years. However, the terms of the freedom of action of the US forces in that installation has remained unclear and it is not a trivial aspect in consideration of the important installations that the US has progressively built on the islands and which has nearly 2,000 soldiers (and over a thousand civilian contractors, mostly Filipinos, engaged in logistic and support functions), as well as airports, seaports, depots and logistic bases of all kinds and communication and electronic interception centres.

Unconfirmed rumors reported that in recent years Washington had started very discreet negotiation with Mauritius regarding whether they had a free hand for their activities in Diego Garcia (in the sense of not needing to give justifications regarding the movement of vehicles and personnel, operations to and in third countries), and that they would “convinced” London to cede its sovereignty to Port Louis.

But the question is much more than the important geostrategic location of the archipelago. In fact, there are options of an institutional type for Great Britain (and in particular its difficult relations with the EU), such as transforming the Chagos into a territory of autonomous overseas under British sovereignty, with a status similar to that of Gibraltar or the Falklands (the Chagos, despite the opinion of the ICJ, mandated by the UN General Assembly, are not included in the list of non-autonomous territories established by the same General Assembly and which include both Gibraltar and the Falkands; Mauritius also claims sovereignty over the islet of Tromelin, uninhabited, and administered by France but which has no military installations there and which is also not included in the list of non-self-governing territories).

And precisely these two British territories reacted to the announcement of the negotiations between the United Kingdom and Mauritius. In the Falklands, the local legislative assembly issued a statement, saying that the situation of the South Atlantic archipelago, claimed by Argentina, “cannot be compared” to that of the Chagos. The text recalled that, in a referendum in 2013, 99.8% of Falklands voters supported British sovereignty. Local lawmakers insist there can be no negotiations over Falklands sovereignty unless the islanders themselves ask for it.

On the same day, the Argentine Foreign Ministry interpreted the matter in a very different way. The South American country believes that the decision on the Chagos is a “precedent” that makes Argentina’s claim to sovereignty “stronger” over the Falklands and is asking the United Kingdom for negotiations. And in Gibraltar, the chief minister, Fabian Picardo, recalled in a tweet that in 2002 the people of Gibraltar “voted ‘no’ to dilute” their “exclusive British sovereignty, from the 99%.”

On the other hand, the Spanish ambassador to the UN, Agustín Santos, stated last June that the ICJ’s decision on the Chagos was “a living doctrine” to resolve a colonial dispute; and this when Gibraltar, Great Britain, Spain, and the EU are involved in an intricate negotiation to find an acceptable compromise for the small British colony that wants to maintain its ties with London, but to be included in the Union’s economic and customs mechanism, and to join (with reservations) the Schengen system and not give in to the persistent Madrid claims to enforce the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) which provides for the return of the British colony to Spain.

A final consideration on the post-Brexit return to the “East of Suez,” outlined in a 2017 doctrinal document from the authoritative King’s College, East of Suez: A British Strategy for the Asian Century. In 2021 the naval group of the British aircraft carrier Queen Elizabeth operated in the waters of the Pacific, but the presence in the region still remains spotty; in fact, only a few elements of the police of the Ministry of Defense are present on Pitcairn Island (now two, recently there were five). In Singapore there is the British Defense Singapore Support Unit (BDSSU), headquartered at the port of Sembawang (Naval Party 1022), with 33 units. The British Military Garrison, Brunei (BMB) has a battlegroup, consisting of a Gurkha unit, and command, support and logistics units. Finally, there is the recently strengthened presence in South Korea: about twenty elements divided between the UNC (UN Command) and the UNC MAC (Military Armistice Commission), led by the brilliant general of the paratroopers, Andrew Harrison, now deputy commander of the multinational force. To this must be added the hundreds (or slightly less) of soldiers with liaison functions (or unspecified functions) in the Australian and New Zealand armed forces.

While the British presence is still limited in the Indo-Pacific, in regards to “East of Suez,” the British forces in the Gulf, Middle East and East Africa are more substantial, with bases, military and civilian personnel and diversified functions in Kenya, Djibouti, Somalia , Yemen, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, Iraq.

Finally, mention should be made of London joining the consolidated FPDA (Five Powers Defense Arrangement), which, according to British plans, should grow in profile and participation in the newly established AUKUS pact (Australia-UK-US), the terms of which are still pending definition; and Japan has recently signed an agreement to strengthen military ties with London. So, let us see what the future brings.

Enrico Magnani, PhD is a UN officer who specializes in military history, politico-military affairs, peacekeeping and stability operations. (The opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations).