There are posthumous editions that are only of secondary interest in relation to the work already known by their author. Such is not the case with this work, written by Derrida in 1960. It cannot be reduced to its sole pedagogical aim, which was to provide the learned correction of a dissertation subject given to his philosophy students at the Sorbonne, on a subject that is none other than a sentence written by Alain: “To think is to say no.” Indeed, in his Preface, Brieuc Gérard stresses that Derrida, then an assistant in “general philosophy and logic” at the university of the Sorbonne, enjoyed for four years “a complete autonomy as to the subject-matter of his courses and the organization of his directed works,” which ceased in 1964 when he was forced to follow the program of the agrégation of philosophy at the École normale supérieure of Paris. In virtue of this autonomy, proper to any enterprise of “general philosophy,” Derrida thus professed his own thought through those he taught. By the mediation of the philosophers that he summoned and discussed, according to a well determined direction leading to his master Heidegger, Derrida who became one of the greatest thinkers of “French Theory” gives us to read and to think the most important premises of his philosophy of deconstruction.

Deconstruction

The title given by Derrida to his four-session essay thwarts the reader’s expectations—instead of representing an apology of negation, in the logical sense of the term, it first follows faithfully Alain’s original proposal to lead to a thought of “neither yes nor no,” where the implications and presuppositions that organize the two affirmative and negative modalities of thought are deconstructed, that is to say, unpacked, and not eliminated. The opposition that Alain makes between thought and affirmation begins in fact, at first, by being translated in the terms of an opposition between thought and belief—for him, Derrida tells us, “the idea of proof as a technical instrument of truth is to be refused, because as soon as one says yes, one ceases to think and one begins to believe.” In this sense, Alain, more Cartesian than Descartes, would adopt an “ultraradicalism of doubt” which consisted in not using it to reach a certainty under the aegis of a veracious God, but on the contrary in remaining at “the hypothesis of the deceitful God and even of the Evil Genius to save thought and the initiation of thought… which has no initiation except in the “no,” hostile to any proof, to any definitive destination in the true.

Even before opposing the ready-to-think provided against it by “the world, the tyrant and the preacher,” the thought is thus constituted by a movement of negation: on the one hand, negation of appearance, insofar as to think, that is to say, to examine objects and to reflect on them, is to refuse to stick to what one perceives; on the other hand and above all, negation of what one holds oneself to be apparent, since “in order to see something, necessitates [already] a whole implicit work of selections, criticisms, questions;” that is to say, of negation of what one excludes in our perceptual sorting: “to believe everything, therefore to say yes to everything, is to choose to see nothing,” Derrida comments. To say yes, one must say no.

In fact, this raises an objection to Derrida, in that this total affirmation, instead of being only a total deprivation of the visible, can be, on the contrary, under different conditions of the rational or discursive thought, the way of access to the invisible itself. Doesn’t the naive “yes to everything” deserve to be measured and rethought by the “I choose everything” of Saint Therese of Lisieux?

Notwithstanding what the saint may object to in the dialectician, Derrida pursues Alain’s reasoning, whose antithesis does not fail to put classical skepticism out of the game: if belief signifies a halt in the movement of thought, its being put to sleep, it is only as “credulous thought.” On the contrary, faith, in its broad sense of an act of trust, is not naive credulity, but the inevitable presupposition of all awakened thought, of all thought that says no: “without a kind of primitive axiological adherence to the legitimacy of truth, it would not even be possible to challenge opinion in general… as a de facto breach of the truth.” In other words, to be able to deny, one has to feel that one has to do so: to say no, one has to have confidence in truth as an ideal against which an opinion can be refuted because it is wrong: “to say no, to doubt, to refuse, one has to want to, to decide to. It is a necessary fiat or a be that is a yes to the will to say no.” The actuality of doubt is based, if not on the ideal certainty in the truth, at least on a confidence in it. To say no, one must say yes.

By showing that thought says neither yes nor no, Derrida leads to the deconstruction of affirmation and negation. This in a double sense: by revealing, on the one hand, the negation supposed by affirmation (in the form of a sorting, a selection) as well as the affirmation supposed by negation (in the form of a confidence in one’s own project), he denies—on the other hand, the pretension of both to represent two modalities of thought, each one provided with its own and definite meaning. In so doing, Derrida challenges classical logic and ontology, which respectively make non-being and negation the symmetrical opposites of being and affirmation, in order to disseminate the meaning of these two opposites in the variety of their mutual implications.

Dissemination

While following Bergson, Derrida notes that negation in classical logic is not a negation; it is only a “modalization” of affirmation, since it consists in refusing an affirmation in the name of another implicit affirmation. For example, to say that such and such a table is not white is to affirm in disguise that the table is of another color. This is why, in the same way, the nothingness in the classical ontology is not a nothingness either, because if it is a nothingness; it is nothing at all; we don’t have to talk about it; it is thus, on the contrary, under the mode of “the haunting” that it means something: “it is necessary that the nothingness haunts being so that negation is possible.” The negation, logical or ontological, must therefore be rethought. By ending his course on Heideggerian phenomenology, Derrida announces what his philosophy will be based on: a renewed thought of negation. For a negation to be really such, in fact, it is necessary, while remaining discursive (without which there is no judgment), that it is the affirmation of nothing. For there to be negation, it must not be a contrary affirmation, but the contrary of any affirmation; consequently, not the determination or definition of any meaning, but the dissemination of meaning.

Derrida has indeed a neantizing conception of freedom. He repeats in his course that humanity experiences its freedom only through its power of “neantization” of the world, of negation of everything: “for my affirmative judgment to have a value of truth,” he says, commenting on Bergson, “it is necessary that I be free to choose for the truth and that I be able to say something other than what I say;” that is to say, to negate the truth. It is thus “by the negation or the thought of nothingness that the spirit authenticates itself as freedom,” he concludes. However, it was Bergson’s mistake, as well as Husserl’s and finally Sartre’s after him, to think negation incompletely: if, indeed, consciousness that denies all existence does not deny itself as existence (or as “being”), its negation is not complete. To affirm its freedom, the subject must be able to deny itself also, to include itself in the hyperbolic negation: “The most comprehensive phenomenological reduction, the most extended, the deepest anguish [will be able] to negate the totality of the world, the totality of the states, the totality of the regions of the being [only by negating also] the man, the for-itself, the consciousness included. It is thus necessary to exceed this opposition consciousness-world.

This is what Heidegger finally understood when, abandoning his theme of anguish, he refused to affirm the power of neantisation “from to be [or] from being,” and to think it on the contrary from “the difference between to be and being,” by which “to be shows itself by hiding itself in being.” Indeed, for Heidegger, nothingness haunts everything, since everything appears and disappears on a purely undetermined background—the fact that any phenomenon can appear and disappear indicates to us that any phenomenon always rests on an empty place; that nothingness is not the opposite of existence but its condition of appearance, as a blackboard allows any form to be drawn on it. But as long as we remain in the order of logically measurable language, this Heideggerian theory of “ontological difference” is an error, since logically speaking, “there is only difference within a genus, [and] being is not a genus.” To assume the ontological difference, it is thus necessary, for Derrida, to make language incommensurable, to subtract it from any possibility of logical measurement, by thwarting any attempt to fix meaning, to define it. Such was the Derridean enterprise of the “dissemination”—once deconstructed the sense of the words, necessarily, instead of recomposing what has been deconstructed, leave the elements of sense scattered, without a coherence definitively assignable to a system or to a given interpretation; it is necessary to let the elements show themselves scattered in an irremediable multiplicity and without substance. Derrida thus saveed the coherence of the Heideggerian phenomenology by exceeding it in a more radical theory—that of the meontological “differentiation,” true contrary thought of to be.

Unbinding

The “differentiation” that Derrida theorized consisted in substantiating the insubstantivable—not the fact of differentiating one thing from another, but the fact of deferring in time the meaning of a concept by its inscription, in a chain of other concepts. Against the traditional principle of identity which, at the foundation of the other principles (of contradiction and of the third-excluded), stipulates that “every thing is what it is,” “A is A,” the course “Thinking” is saying no; it intends to show that the two fundamental elements of language, the yes and the no, have no determined meaning—the yes is not a yes, the no is not a no, since their meaning is always deferred, awaiting donation through the diversity of their uses and their mutual implications. We thus understand why Derrida concluded his course by saying that Heidegger’s “ontico-ontological difference” “would allow us to really hear Alain when he says that ‘to think is to say no'”: this thought indeed opens a breach in the possibility of thinking a negation that is really one, by preventing any determination, any assignment of any meaning whatsoever to a given sign by disseminating it, by always ceaselessly deferring the sign from itself.

The Deconstruction inaugurated by Derrida is thus much more subtle, and therefore more pernicious, than what many contemporaries understand it to be by associating it, wrongly, with an enterprise of pure and simple destruction. Derrida does not destroy anything—he deconstructs to disseminate, to untie. He exhibits the constructions of thought and language, without suppressing them nor recomposing them, by leaving them “disseminated” out of any possibility of stable recomposition. To the antipodes of the philosopher Albert Leclère who, in 1901, defended in his Essai critique sur le droit d’affirmer (Critical Essay on the Right to Affirm) that “the thinking subject cannot consider thought without immediately noticing that it poses the existence of some reality,” concluding that “the reality of being, of metaphysical being, is a necessary affirmation of thought.” On the contrary, Derrida wrote, sixty years later, a succession of essays to show the necessity, for thought, of denying. All of Derrida’s originality is to see to it that this negation is a true negation; that is to say, not a contrary affirmation, but the contrary of any affirmation—this is why he considered that “to criticize a philosopher is a lamentable gesture” and, refusing all criticism, does not seek to refute but to dissolve the problems by taking care to never completely satisfy the need for comprehension, by thwarting all attempts at definition.

Derrida thus represents the most coherent attempt to dissolve the traditional philosophical “realism” of a Saint Thomas Aquinas, by denying to signs not only their connection to things, to which they refer (as the nominalists were content to do), but also their capacity to coincide with their own meaning. If, from this course, the sense is untied from the real (“the noem is nothing real since it is a sense,” he infers about Husserl), the sense announces itself similarly to be untied from itself in the justification of the thought as “saying no.” Thus, it is not excluded to think that Derrida completed, in the 20th century, the whole process of desubstantialization of language inaugurated by nominalism from the 14th century, completing the modernization of thought in an enterprise of final dissolution of meaning.

Paul Ducay, Professor of philosophy with a medievalist background. Heir to the metaphysics of Nicolas de Cues and the faith of Xavier Grall. Gascon by race and French by reason. “The devout infuriate the world; the pious edify it.” Marivaux. [This article comes through the kind courtesy of PHILITT].

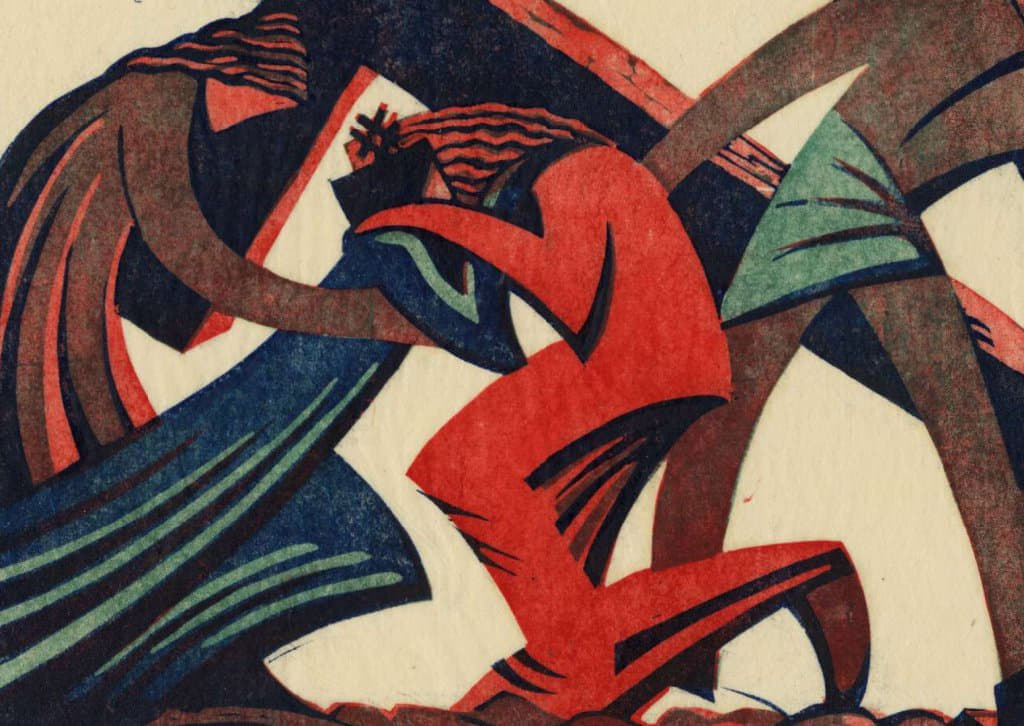

Featured: “Via Dolorosa,” by Sybil Andrews; linocut print, 1935.