On May 11, 330 AD, on the European coast of the Bosporus, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great solemnly founded the new capital of the empire – Constantinople (or, to be precise, and use its official name at that time – New Rome). The emperor did not create a new state: Byzantium in the exact sense of the word was not the successor of the Roman Empire, it was itself – Rome. The word “Byzantium” appeared only in the West during the Renaissance. The Byzantines called themselves Romans; their country they called the Roman Empire. Constantine’s intentions corresponded to this name. New Rome was erected at a major crossroads of major trade routes and was originally planned as the greatest of cities. Built in the 6th century, the Hagia Sophia Cathedral was the tallest architectural structure on the earth for over a thousand years, and its beauty was compared to Heaven.

Until the middle of the 12th century, New Rome was the main trading hub of the planet. Before the destruction by the crusaders in 1204, it was also the most populated city in Europe. Later, especially in the last century and a half, centers of greater importance, in the economic sense, appeared on the globe. But even in our time, the strategic importance of this place would be difficult to overestimate.

Possessing the straits of the Bosporus and the Dardanelles, meant owning the entire Near and Middle East; and this is the heart of Eurasia and the entire Old World. In the 19th century, the British Empire was the real master of the straits, protecting this place from Russia even at the cost of an open military conflict (the Crimean War of 1853-1856, and the possibility of war in 1836 or 1878). For Russia, it was not just a matter of “historical heritage,” but the ability to control its southern borders and main flow of trade.

After 1945, the keys to the straits were in the hands of the United States, and the deployment of American nuclear weapons in this region, as we know, immediately caused the appearance of Soviet missiles in Cuba and provoked the Cuban missile crisis. The USSR agreed to retreat only after the US nuclear potential in Turkey was phased out. Nowadays, the issues of Turkey’s entry into the European Union and its foreign policy in Asia are the primary problems for the West.

They Only Dreamed Of Peace

New Rome received a rich legacy. However, this also became its main “headache.” In the modern world there were too many applicants for the appropriation of this inheritance. It is difficult to recall even one long period of calm on the Byzantine borders; the empire was in mortal danger at least once each century.

Until the 7th century, the Romans along the perimeter of all their borders fought the most difficult wars with the Persians, Goths, Vandals, Slavs and Avars, and ultimately the confrontation ended in favor of New Rome. This happened very often: young and fresh peoples who fought with the empire went into historical oblivion, and the empire itself, ancient and almost defeated, licked its wounds and continued to live. Then, the former enemies were replaced by the Arabs from the south, the Lombards from the west, the Bulgarians from the north, and the Khazars from the east, and a new centuries-old confrontation began. As the new opponents weakened, they were replaced in the north by the Rus, Hungarians, Pechenegs, Polovtsians, in the east by the Seljuk Turks, in the west by the Normans.

In the fight against enemies, the empire used force, honed over centuries of diplomacy, intelligence, military cunning, and sometimes the services of allies. The last resort was double-edged and extremely dangerous. The crusaders who fought with the Seljuks were extremely burdensome and dangerous allies for the empire – and this alliance ended with the first fall of Constantinople: the city, which had successfully fought off any attacks and sieges for almost a thousand years, was brutally ravaged by its “friends.”

Its further existence, even after the liberation from the crusaders, was only a shadow of the previous glory. But just at this time, the last and most cruel enemy appeared – the Ottoman Turks, who surpassed all previous enemies in their military qualities. The Europeans really got ahead of the Ottomans in military affairs only in the 18th century – and the Russians were the first to do this; and the first commander who dared to appear in the inner regions of the Sultan empire was Count Peter Rumyantsev, for which he received the honorary name the Transdanubian.

Irrepressible Subjects

The internal state of the Roman Empire was also never calm. Its state territory was extremely heterogeneous. At one time, the Roman Empire maintained unity through superior military, commercial and cultural potential. The legal system (the famous Roman law, finally codified in Byzantium) was the most perfect in the world. For several centuries (since the time of Spartacus) Rome, within which more than a quarter of all mankind lived, was not threatened by a single serious danger.

Wars were fought on distant borders – in Germany, Armenia, Mesopotamia (modern Iraq). Rather, internal decay, a crisis in the army and a weakening of trade led to disintegration. Only from the end of the 4th century did the situation on the borders become critical. The need to repel barbaric invasions, from different directions, inevitably led to the division of power in a huge empire among several peoples. However, this also had negative consequences – internal confrontation among these people, further weakening of ties, and the desire to “privatize” their piece of imperial territory. As a result, by the 5th century, the final division of the Roman Empire became a fact, but did not alleviate the situation.

The eastern half of the Roman Empire was more populated and Christianized (by the time of Constantine the Great, Christians, despite persecution, already comprised more than 10% of the population), but in itself did not constitute an organic whole. An amazing ethnic diversity reigned in the state: Greeks, Syrians, Copts, Arabs, Armenians, Illyrians lived here; soon there were Slavs, Germans, Scandinavians, Anglo-Saxons, Turks, Italians and many other nationalities, from whom only the confession of true faith and submission to the imperial power were required. Its richest provinces – Egypt and Syria – were geographically too remote from the capital, fenced off by mountain ranges and deserts. Maritime communication with them, as trade declined and piracy flourished, became more and more difficult.

In addition, the overwhelming majority of the population in Egypt and Syria were adherents of the Monophysite heresy. After the victory of Orthodoxy at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, a powerful uprising broke out in these provinces, which was suppressed with great difficulty. Less than 200 years later, the Monophysites greeted the Arab “liberators” with joy and subsequently converted to Islam relatively painlessly.

The western and central provinces of the empire, primarily the Balkans, but also Asia Minor, for many centuries experienced a massive influx of barbarian tribes – Germans, Slavs, and Turks. Emperor Justinian the Great in the 6th century tried to push the state boundaries in the west and restore the Roman Empire within its “natural borders,” but this led to colossal efforts and costs. Then, a century later, Byzantium was forced to shrink to the limits of its “state core,” mainly inhabited by Greeks and Hellenized Slavs. This area included the west of Asia Minor, the Black Sea coast, the Balkans, and southern Italy. The further struggle for existence was mainly taking place in this territory.

The People And The Army Are One

Constant struggle required constant maintenance of defenses. The Roman Empire was forced to revive the peasant militia and the heavily armed cavalry army, characteristic of ancient Rome of the republican period, to re-create and maintain a powerful navy at the state’s expense.

Defense had always been the main expense of the treasury and the main burden for the taxpayer. The state always ensured that the peasants retained their combat capability; and, therefore, in every possible way strengthened the community, preventing its disintegration. The state struggled with the excessive concentration of wealth, including land, in private hands. Government price regulation was a very important part pf policy. The powerful state apparatus, of course, gave rise to the omnipotence of officials and large-scale corruption. Active emperors fought against abuse; inept emperors brought about troubles.

Of course, weakened social stratification and limited competition slowed down the pace of economic development, but the fact of the matter is the empire had more important tasks to look after. It was not to ensure a good life that the Byzantines equipped their armed forces with all sorts of technical innovations and many types of weapons, the most famous of which was “Greek fire,” invented in the 7th century, which gave more than one victory to the Romans.

The army of the empire retained its fighting spirit until the second half of the 12th century, when it gave way to foreign mercenaries. The Treasury began to spend less, and the risk of falling into the hands of the enemy increased immeasurably. Let us recall the classic expression of one of the recognized experts on the issue – Napoleon Bonaparte: the people who do not want to feed their army will feed someone else’s. From that time on, the empire began to depend on Western “friends,” who immediately showed just how friendly they could be.

Autocracy As Necessity

The circumstances of Byzantine life strengthened the conscious need for the autocratic power of the emperor. But too much depended on his personality, character, abilities. That is why the empire developed a flexible system of transferring supreme power. In specific circumstances, power could be transferred not only to the son, but also to the nephew, son-in-law, brother-in-law, husband, adopted successor, even to the emperor’s own father or mother. The transfer of power was consolidated by the decision of the Senate and the army, popular approval, church wedding (from the 10th century, the practice of imperial chrismation was also introduced, borrowed from the West).

As a result, imperial dynasties rarely saw centenaries; only the most talented among them – the Macedonian dynasty managed to hold out for almost two centuries – from 867 to 1056. A person of low origin, who was promoted thanks to one or another talent (for example, Leo I, the butcher from Dacia; Justin I, a commoner from Dalmatia and the uncle of Justinian the Great; or the son of an Armenian peasant. Basil the Macedonian, the founder of that very Macedonian dynasty) could also be on the throne.

The tradition of co-government was highly developed (co-rulers sat on the Byzantine throne for about two hundred years). Power had to be firmly held – in the entire Byzantine history, there were about forty successful coups d’état; usually they ended with the death of the defeated ruler, or his removal to a monastery. Only half of the emperors died on the throne.

Empire As A Katechon

The very existence of the empire was for Byzantium more a duty and a debt than an advantage or a rational choice. The ancient world, the only direct heir of which was the Empire of the Romans, became the historical past. However, its cultural and political heritage became the foundation of Byzantium.

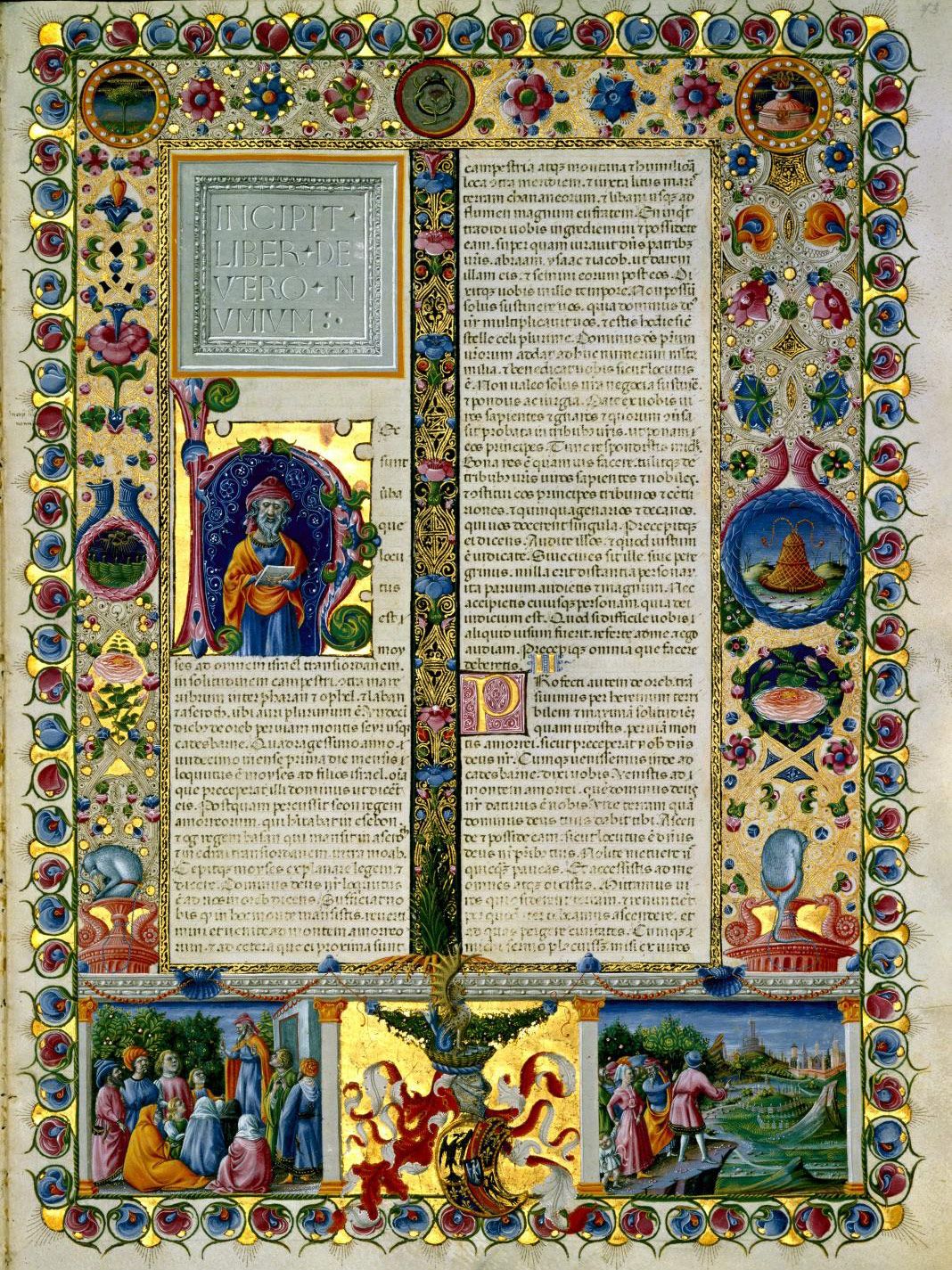

Since the time of Constantine, the empire had also been a stronghold of the Christian faith. The state political doctrine was based on the idea of the empire as a “katechon” – the keeper of the true faith. The barbarian Germans, who filled the entire western part of the Roman oecumene, adopted Christianity, but in the Arian heretical version. The only major “acquisitions” of the Ecumenical Church in the West, until the 8th century, were the Franks.

Having accepted the Nicene Creed, the Frankish king Clovis immediately received the spiritual and political support of the Roman Patriarch-Pope and the Byzantine emperor. From this began the growth of the power of the Franks in western Europe: Clovis was granted the title of Byzantine patrician, and his distant heir Charlemagne, three centuries later, wanted to be called the emperor of the West.

The Byzantine mission of that period could well compete with the Western one. Missionaries of the Church of Constantinople preached in the area of Central and Eastern Europe – from Bohemia to Novgorod and Khazaria; the English and Irish local Churches maintained close contacts with the Byzantine Church. However, papal Rome quite early became jealous of competitors and expelled them by force; and soon the mission itself in the papal West acquired an openly aggressive character and predominantly political task. The first large-scale action, after the fall of Rome from Orthodoxy, was the papal blessing of William the Conqueror to march to England in 1066. After that, many representatives of the Orthodox Anglo-Saxon nobility were forced to emigrate to Constantinople.

Within the Byzantine Empire itself, there were heated debates on religious grounds; and among the people, now in power, heretical trends arose. Under the influence of Islam, the emperors began iconoclastic persecutions in the 8th century, which provoked resistance from the Orthodox people. In the 13th century, out of a desire to strengthen relations with the Catholic world, the government went to union, but again did not receive support. All attempts to “reform” Orthodoxy on the basis of opportunistic considerations, or to bring it to conform to “earthly standards” have failed. The new union in the 15th century, concluded under the threat of the Ottoman conquest, could no longer ensure even political success. Such a union became history’s bitter grin at the vain ambitions of the rulers.

What Is The Advantage Of The West?

When and in what ways did the West begin to gain the upper hand? As always, in economics and technology. In the field of culture and law, science and education, literature and art, Byzantium, until the 12th century easily competed or far outstripped its western neighbors. The powerful cultural influence of Byzantium was felt in the West and East far beyond its borders – in Arab Spain and Norman Britain, and in Catholic Italy it dominated until the Renaissance. However, due to the very conditions of existence of the empire, it could not boast of any special socio-economic success.

In addition, Italy and Southern France were initially more favorable for agricultural activities than the Balkans and Asia Minor. In the 12th-14th centuries in Western Europe there was a rapid economic upturn – the kind that did not exist since ancient times and will not be seen again until the 18th century. It was the heyday of feudalism, papacy and chivalry. It was at this time that a special feudal structure of Western European society, with its estate-corporate rights and contractual relations, arose and took root (the modern West came out of this).

Western influence on the Byzantine emperors from the Komnenian dynasty in the 12th century was strongest – they copied Western military art, Western fashion, and for a long time acted as allies of the crusaders. The Byzantine fleet, so burdensome for the treasury, was dissolved. Its place was taken by flotillas of the Venetians and the Genoese. The emperors cherished the hope of overcoming the not-so-long-ago falling away of papal Rome. However, strengthened Rome by now recognized only complete submission to its will. The West marveled at the imperial brilliance and, in justification of its aggressiveness, loudly resented the duplicity and depravity of the Greeks.

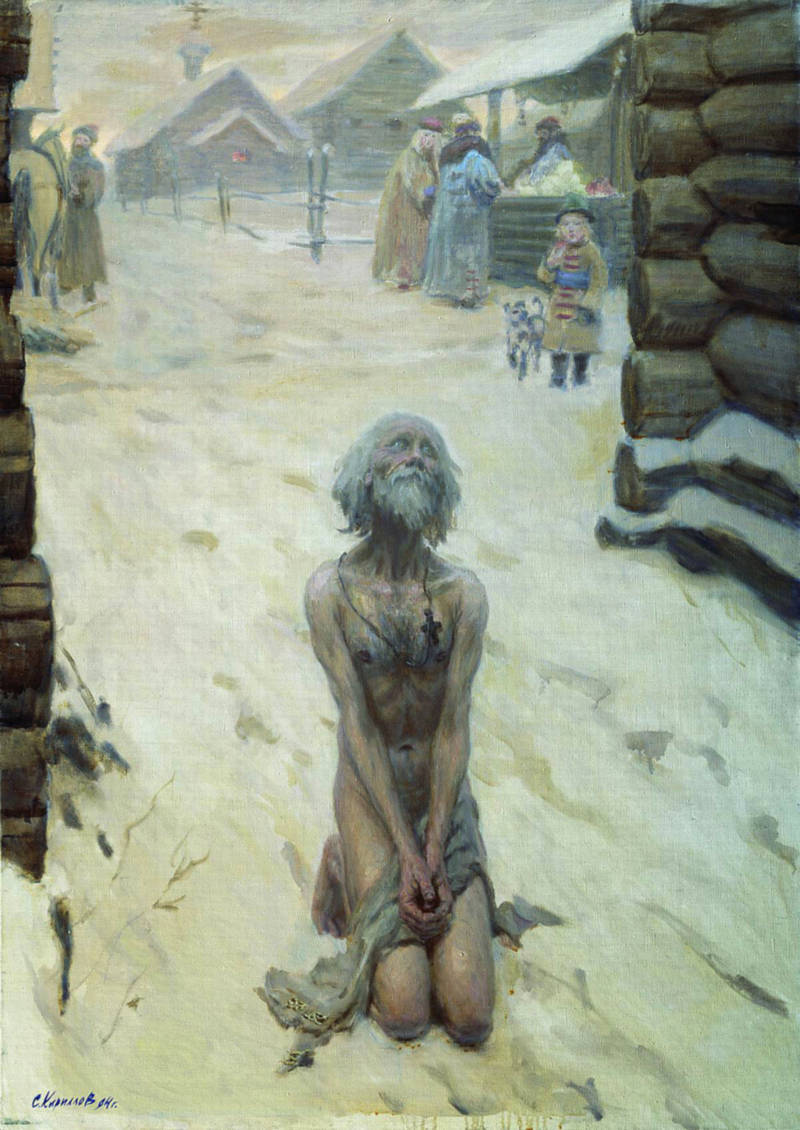

Did the Greeks drown in debauchery? Sin coexisted with grace. The horrors of palaces and city squares were interspersed with the genuine sanctity of the monasteries and the sincere piety of the laity. This is evidenced by the lives of the saints, liturgical texts, lofty and unmatched Byzantine art. But the temptations were very strong.

After the defeat of 1204 in Byzantium, the pro-Western trend only intensified – young people went to study in Italy; and among the intelligentsia there was a craving for the pagan Hellenic tradition. Philosophical rationalism and European scholasticism (based on the same pagan scholarship) began to be viewed in this environment as higher and more refined teachings than patristic ascetic theology. Intellect prevailed over Revelation, individualism over Christian exploit. Later, these tendencies, together with the Greeks who moved to the West, would greatly contribute to the development of the Western European Renaissance.

Historical Scale

The empire survived the fight against the crusaders. On the Asian coast of the Bosporus, opposite the defeated Constantinople, the Romans retained their territory and proclaimed a new emperor. Half a century later, the capital was liberated and held out for another 200 years. However, the territory of the revived empire was practically reduced to the greatest city, several islands in the Aegean Sea and small territories in Greece. But even without this epilogue, the Empire of the Romans existed for almost a whole millennium.

In this case, one can even ignore the fact that Byzantium directly continued ancient Roman statehood, and considered the foundation of Rome in 753 BC to be its birth. Even without these reservations, there is no other such example in world history. Empires have existed for years (Napoleon’s Empire: 1804–1814), for decades (German Empire: 1871–1918), at best for centuries. The Han Empire in China existed for four centuries; the Ottoman Empire and the Arab Caliphate a little more, but by the end of their life cycle they became only a part of the story of empires. The West-based Holy Roman Empire of the German nation was also a fiction for most of its existence.

There are not so many countries in the world that claimed imperial status and then continuously existed for a thousand years. Finally, Byzantium and its historical predecessor – ancient Rome – also demonstrated a “world record” for survival – any state on earth withstood, at best, one or two global alien invasions – Byzantium withstood many more. Only Russia can be compared with Byzantium.

Why Did Byzantium Fall?

Her successors have answered this question in different ways. At the beginning of the 16th century, the Pskov elder Philotheus believed that Byzantium, having accepted the union, had betrayed Orthodoxy, and this was the reason for its death. However, he argued that the death of Byzantium was conditional: the status of the Orthodox Empire was transferred to the only remaining sovereign Orthodox state – Moscow.

In this, according to Philotheus, there was no merit of the Russians themselves, such was God’s will. However, the fate of the world now depended on the Russians – if Orthodoxy falls in Russia, then the world will soon end with it. Thus, Philotheus warned Moscow about its great historical and religious responsibility. The Palaeologus coat of arms inherited by Russia – the double-headed eagle – is a symbol of such responsibility, a heavy cross of the imperial burden.

The elder’s younger contemporary Ivan Timofeev, a professional warrior, pointed to other reasons for the fall of the empire: the emperors, trusting in flattering and irresponsible advisers, despised military affairs and lost their combat readiness. Peter the Great also spoke about the sad Byzantine example of the loss of fighting spirit, which became the cause of the death of the great empire, in a solemn speech delivered in the presence of the Senate, Synod and generals in the Trinity Cathedral of St. Petersburg on October 22, 1721, on the day of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, when he became king and received the imperial title.

As we can see, all three – the elder, the warrior and the newly proclaimed emperor – had in mind similar things, only in different aspects. The power of the Empire of the Romans rested on a strong power, a strong army and the loyalty of its subjects. But all of them had to have a firm and true faith as the foundation. And in this sense, the empire, or rather all the people who made it up, always balanced between Eternity and death.

The constant relevance of this choice is an amazing and unique aspect of Byzantine history. In other words, this story in all its light and dark sides is a vivid testimony to the correctness of the saying from the rite of the Triumph of Orthodoxy: “This is the apostolic faith, this is the faith of the Fathers, this is the Orthodox faith, confirm this universal faith!”

Fedor Gaida is Associate Professor in the Faculty of History, Lomonosov Moscow State University. His research interests include, the political history of Russia at the beginning of the 20th century; Russian liberalism; power and society in a revolutionary era; Church and Revolution.

The image shows, “The Anastasis,” a wall painting from the Parekklesion of the Chora Monastery, Istanbul, Turkey, ca. 1321.

The Russian version of this article appeared in Provoslavie.