There are certain ideas that, once introduced, tend to change how people think of everything else. This is certainly the case with the Bible. For of all the ideas about the Scripture, the most recent is the notion of “the Bible.”

The word “Bible” simply means “book.” Thus, it is a name that means “the Book.” It is a particularly late notion if for no other reason than that books are a rather late invention. There are examples of bound folios of the New Testament dating to around the 4th century, but they may very well have been some of the earliest examples of such productions.

The Emperor Constantine commissioned a large number of such copies (all produced by hand) as gifts to the Bishops of the Church. How many such editions is unknown, though it may have been several hundred. One of the four manuscripts dating to the 4th century may very well be a survivor of that famous group.

In the Church (and to this day in Orthodoxy), the gospels are bound as one book and the Epistles, etc., are bound as another. And these are only those books appointed for reading in the Church. The Revelation is not usually included in such editions.

The “Bible,” a single book with the whole of the Scriptures included, is indeed modern. It is a by-product of the printing press, fostered by the doctrines of Protestantism. For it is not until the advent of Protestant teaching that the concept of the Bible begins to evolve into what it has become today.

The New Testament uses the word “scriptures” (literally, “the writings”) when it refers to the Old Testament, but it is a very loose term. There was no authoritative notion of a canon of the Old Testament. There were the Books of Moses and the Prophets (cf. Luke 24:27) and there were other writings (the Psalms, Proverbs, etc.).

But writers of the New Testament seem to have had no clear guide for what is authoritative and what is not. The book of Jude makes use of the Assumption of Moses as well as the Book of Enoch, without so much as a blush. There are other examples of so-called “non-canonical” works in the New Testament.

It is difficult on this side of the Reformation for people to have a proper feel for the Scriptures. First, though we say “Scriptures” (sometimes) we are just as likely to say “Scripture” (singular) and always have that meaning in mind regardless. We think of the Scriptures as a single book. And with this thought we tend to think of everything in the Book as of equal value, equal authenticity, equal reliability, equal authority, etc. And this is simply not the case and never has been.

The New Testament represents, in various forms, the Christian appropriation and re-reading of the Scriptures of Pharisaic Judaism (or even wider). The writings in the Old Testament do not, of themselves, point to Christ or prove that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah. The Jews of Christ’s time, though expectant of a Messiah (God’s “Anointed One”), did not expect such a one to be the Son of God, nor Divine, nor to be crucified dead and resurrected.

All of these understandings with regard to Christ are understandings that are post-resurrectional. The New Testament is quite clear that the disciples understood none of these things until after Christ’s resurrection, despite being told them numerous times. St. Paul, in his Second Letter to the Corinthians describes the failure of the Jews to see Christ in the writings of the Old Testament as a “veil,” and compares it to the veil that Moses put over his face.

Thus the New Testament reading of the Old Testament is a “revelation” (an “apocalypse”) of the “mystery hidden from before all the ages.” Were it clear in the Old Testament, the mystery would not have been hidden. This is a unique and peculiar claim of the primitive Christian community. They present a novel, even apocalyptic interpretation of the writings of Judaism, and describe them as the true meaning of the Scriptures as revealed in Jesus Christ.

This is a world removed from modern (post-Reformation) claims for the Bible. For the equality (in authority, authenticity, etc.) of each writing within the Scriptures only becomes paramount when their individual worth is eradicated in their assumption by the whole. Thus, Joshua suddenly becomes of equal importance with the Pentateuch (the 5 books of Moses) simply by reason of being included in “the Bible.” But historically, the book of Joshua never held the kind of central role that belonged to the Pentateuch. Saying this is not intended to diminish its importance, only to remove an importance to which it is not properly due.

Of course, starting down such a course raises enormous red flags for many. The concern would easily be voiced, “How, then, do you know what is more valuable and what less?” And this brings us back to the proper place. For the role of interpretation, weighing, comparing, etc., is the role of the Church, the believing community.

There can be no Scriptures outside the Church. To say, “Scriptures,” is simply to name those writings which the believing Church holds to be important and authoritative – nothing more and nothing less. St. Hilary famously said, “The Scriptures are not in the reading, but in the understanding” (scriptura est non in legendo, sed in intelligendo).

The creation of a “canon” of Scripture was never more than a declaration of what a general consensus within the Church treated as authoritative. The Scriptures as a place for creating and proving formal doctrine is something of a fiction. 2 Timothy 3:16-17 is the primary verse trotted out in defense of Scriptural authority: “All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, thoroughly equipped for every good work.”

But this is a very troublesome and questionable translation. In Protestant usage, the key phrase is “all Scripture is given by inspiration of God.” But, in fact, the phrase “given by inspiration of God” is a single word (θεόπνευστος), just as accurately translated, “all Scripture that is inspired of God,” thus being a limiting phrase and not one that serves as an authoritative licensing of something later described as “the Bible.”

What we actually have in 2 Timothy is a very homely, parenetic expression in which the author suggests that reading the Scriptures is a good thing. It is not, despite its use as such, a foundational proclamation of the Bible as sole authority. For it is the Church that is described as the “Pillar and Ground of Truth” (1 Timothy 3:15).

And the “canon” of Scripture was historically not a list of authoritative books, but a list of those works commonly read in the Churches. It is, something of a catalog of the lectionary. What we actually find in the Fathers is not the later proof-texting from an authoritative text, the Master Book of All Knowledge, if you will, but a use of quotes that seemed at hand and most useful for whatever topic was being treated.

There are, to be sure, careful expository writings, such as those of St. John Chrysostom and others, but these are what they are: expositions of various writings. When the Church turned to the central core doctrines of the Faith, such as the Trinity, the natures and Person of Christ, the character of salvation, etc., arguments were far more wide-open and non-expository. Reason and language played as much of a role as Scripture itself.

The words homoousios, hypostasis and ousia that play such completely central roles in the foundational doctrines of the Trinity and Christology are not given meanings drawn from Scripture, but from arguments that incorporate Scripture and every possible tool.

The Church is not a Bible-based teaching institution – the Church is the Pillar and Ground of Truth, the Body of Christ, divinely given by God for our salvation and it uses the Scriptures and everything that exists for the purpose of expounding the truth it has received from God from the very beginning.

The only “thing” approaching a “Bible” in the sense that has commonly been used in modern parlance, is the Church. The Scriptures have their place within the life of the Church and only exist as Scriptures within that context.

****

[Protestants will] take me to task for arguing that “books” themselves are late inventions and contending that the Bible was not therefore thought of as a “book.” [They may] cite some early codices from the late 2nd or early 3rd centuries – but [they become] examples that actually reinforce my central point. [They may] note examples of bound gospels and an example of bound epistles. What [they] cite are precisely what we would expect: liturgical items.

The Orthodox still use the Scriptures in this form – the Gospels as a book (it rests on the altar), and the Epistles as a book (known as the Apostol). They are bound in such a manner for their use in the services of the Church, not as private “Bibles.” These are outstanding examples of the Scriptures organized in their liturgical format for their proper use: reading in the Church. They are Churchly items – not “The Book” of later Protestantism. They are the Scriptures of the worshipping Church.

And this is my point. The Scriptures are not “above” the Church nor the Church “above” the Scriptures. The Scriptures are “of” the Church and do not stand apart from the Church.

It is very difficult to have a conversation with certain Protestants. They have a view of the Scriptures as “Bible,” rather than a more contextualized position as part of the life of the Church. Any attempt to rein in their run-away Bible-agenda is seen as an attempt to diminish the Word of God or to exalt the Church to some wicked deceiver of Christians. But this is simply the tired rhetoric of the Reformation. I do not seek to convince readers that the Bible is a problematic construction – rather – Sola Scriptura Christians are problematic interpreters. The fruit of their work bears me out.

Sola Scriptura, as taught and practiced in Protestant thought, is simply wrong and an invention of the Late Medieval and Modern periods. All of the writers cited by [Protestants] for their “lists” of books are eventually described as the “Canon of Scripture,” [and] are Orthodox Christians, mostly priests and bishops. They spoke and thought as the Orthodox do to this day.

They never (!) saw the Bible as a book “over the Church.” These were men of a thoroughly sacramental world. The Bread and the Wine of the Eucharist was universally believed to be the very Body and Blood of Christ. These men ate God (using the language of St. Ignatius of Antioch).

Yes, the Scriptures are theopneustos (“God breathed”), but so is every human soul. The God-breathed character of the Scriptures does not exalt them over us but raises them up to the same level as us. For ancient authorities (and the Orthodox faithful to this day) were Baptized into the death and resurrection of Christ and were thereby united together with Him.

The Church was not and is not “under” the Bible, for it cannot be. Christ is Head of the Church, part of His Body. Is Christ “under the Scriptures?” All of the “lists” that are cited in the notion of the evolution of the Canon are lists of what the Church reads.

And the Church reads them in her services as the Divine Word of God, just as the Church herself is the Divine Body of Christ, just as the Liturgy is the Marriage Supper of the Lamb, etc. The “Canon” of Scripture is as much a statement about the Church as it is about the Scriptures.

But all of this is lost, because for those who have reformed themselves out of communion with the historical faith and practice of Christianity, the context has been forgotten. They do not understand statements about the Church because they have forgotten the Church.

There are crucial tests that can be applied that reveal the truth of things and the errors of Sola Scriptura. The championing of the Bible as the Word of God “over the Church” is a ruse. It is and has been a means of exalting culture and private fiefdoms over the proper life of the believing community, disrupting the continuity of faith.

A very grievous example can be found in the very American reform community from which Kruger criticizes my Orthodox teaching. For the very groups that exalted the Bible as Sola Scriptura, for years also exalted a Bible-based justification for the most egregious racism the world has ever seen. It has been a matter to which reformed Christians are today attending with repentance (to their credit).

But by what criteria did their fathers find such racism in the Scriptures? And by what criteria do they themselves now not find it in the Scriptures? Are they not simply giving voice to various cultural winds and using the Scriptures as a convenient support? Have they not always done this? Today’s proponents of the radical sexual agenda rightly point out that these “Bible-based” teachers have always found Biblical support for their own cultural prejudices. Their history should leave them speechless.

Orthodoxy is not without its sinners. But in the 2000-year unbroken life of the Church, error has never been raised to the place of “Biblical teaching.” The Orthodox have never said that blacks do not have souls.

The Orthodox have never declared one race to be inferior to another. Biblicists do well to repent of such things, but they fail to see that their own hermeneutical principles are at fault. Only a life lived with a true, genuine continuity of the tradition that is the very life of the Church can “rightly divide the word of truth:” Therefore, brethren, stand fast and hold the traditions which you were taught, whether by word or our epistle (2 Thessalonians 2:15).

God promised to the Church that the gates of hell would not prevail. He declared the Church to be the Pillar and Ground of Truth. He revealed the Church to be the Bride of Christ (and I could fill pages with such statements).

This is not to exalt the Church “over” the Scriptures, but to recognize the Scriptures place within the Divine Life of the Church. The Orthodox do not exalt a bishop over the Scriptures, nor do we declare a bishop to be the head of the Church (we declare that to be error).

But we acknowledge that the Scriptures cannot be rightly read outside of and apart from the life of the Church. Such decoupling of the Scriptures has only created false churches, false brethren, and false teaching. No gathering of Christians hears as much Scripture as the Orthodox do in the context of their services. The Orthodox liturgical life is the singing of Scripture in the praise of God (from beginning to end).

But in the name of “Biblical authority” contemporary Christians are today subjected to a growing and continuing phenomenon of rogue organizations built around charismatic personalities with little or no accountability (except to “the Bible” as they see it). Orthodoxy lives by the same rules (canons) that were in effect when the Scriptures were “canonized.”

Those who canonized the Scriptures venerated the Mother of God, honored the saints, prayed for the departed, believed the Eucharist to be the true Body and Blood of Christ. They were the same Orthodox Church that lives and believes today. You cannot honor their “Canon of Scripture” while despising the lives and Church of those who canonized them.

While the Orthodox Church lives the same life under the same canons, reading the same Scriptures as it has always done – those who champion “God’s un-changing Word” and claim to be under the authority of the Bible cannot point to even two decades in which they have remained the same. They are a moving target. It is to be welcomed when they repent of past institutional sins – but their history reveals that they have primarily been subject to the spirit of the age, even if it’s a conservative spirit.

Christ never wrote a word. Christ never commanded his disciples to write a word (an exception being in Revelation). They were commanded to go forth, preach the gospel and to Baptize. Christ established the Church. The Church is the Scriptures and the Scriptures, rightly read, are the Church. This is the declaration of St. Paul to the Church in Corinth: “You are our epistle written in our hearts, known and read by all men; clearly you are an epistle of Christ, ministered by us, written not with ink but by the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of flesh, that is, of the heart” (2 Corinthians 3:2-3).

Is that epistle of less value because it is not written in ink? It is only by being the living Scriptures that the Church can and does truly read and interpret the Scriptures. There is no “Bible” in the Bible.

Father Stephen Freeman is a priest of the Orthodox Church in America, serving as Rector of St. Anne Orthodox Church in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He is also author of Everywhere Present and the Glory to God podcast series.

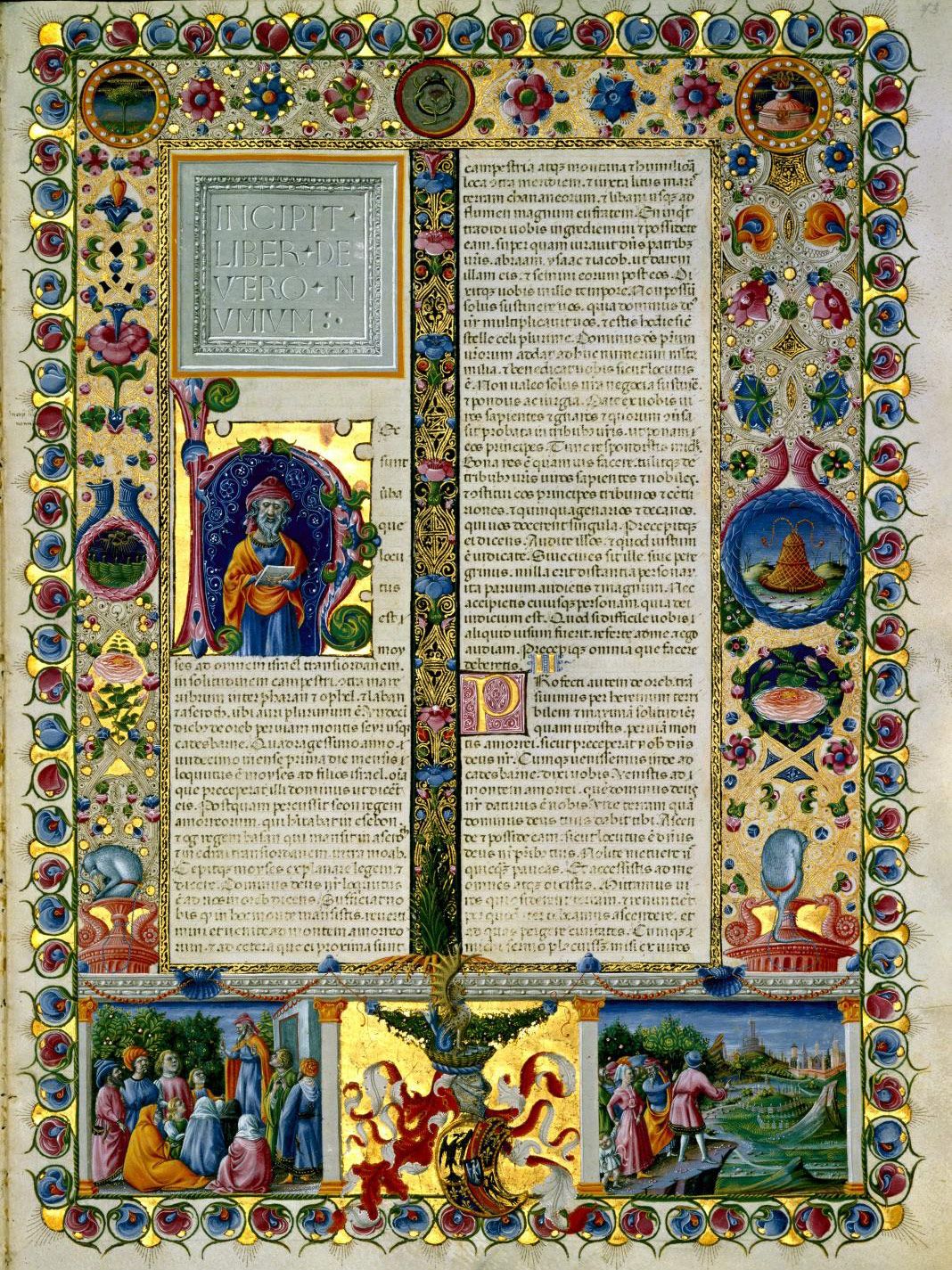

The photo shows a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible, from 1454.