Drawing on the Book of Proverbs, St. Paul offers a simple admonition to his readers:

“…if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals on his head.” (Romans 12:20)

He then adds:

Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.

It is a very simple statement. However, when anyone begins to suggest what that might look like, critics quickly begin to offer egregious examples that would ask us to bear the unbearable, with the inevitable conclusion: “Kill your enemies.” What is suggested, in effect, is that Christians should respond in the same way as any tyrant would, only a little less so. “Kill your enemies, but not so much.” (I use the term “kill” in this example only as the most extreme form of violence). A question: What is it about the Kingdom of God that gave Christ and the Apostles such a confidence in its non-violence?

Consider these verses:

Jesus answered, “My kingdom is not of this world. If My kingdom were of this world, My servants would fight, so that I should not be delivered to the Jews; but now My kingdom is not from here.” (Jn. 18:36)

And

“But now let the one who has a moneybag take it, and likewise a knapsack. And let the one who has no sword sell his cloak and buy one. For I tell you that this Scripture must be fulfilled in me: ‘And he was numbered with the transgressors.’ For what is written about me has its fulfillment.” And they said, “Look, Lord, here are two swords.” And he said to them, “It is enough.” (Lk. 22:38)

And

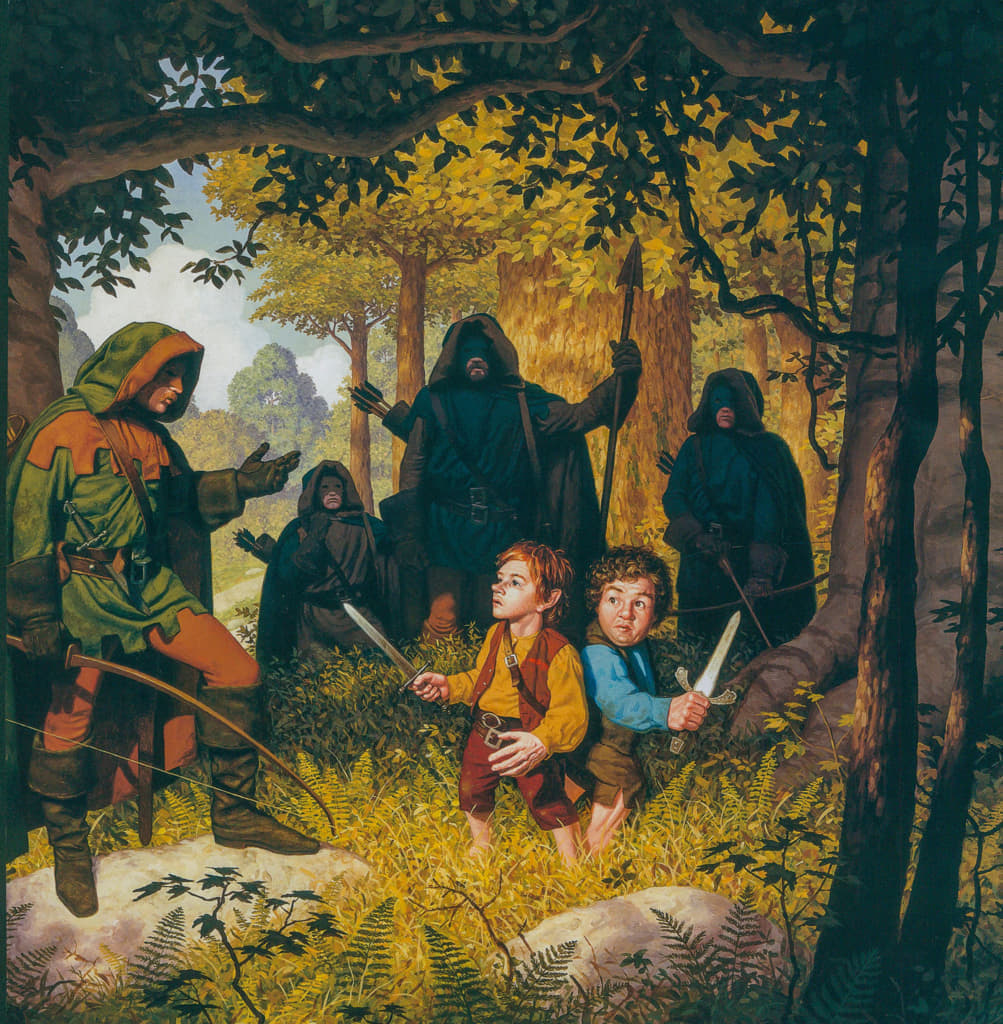

“And behold, one of those who were with Jesus stretched out his hand and drew his sword and struck the servant of the high priest and cut off his ear. Then Jesus said to him, “Put your sword back into its place. For all who take the sword will perish by the sword.” (Matt. 26:52)

There is something of a mystery in Christ’s instruction to buy a sword. Many consider it simply a metaphorical way of saying that troubles are coming. Indeed, one of those two swords is drawn and does terrible damage to a man when Christ is arrested, earning a rebuke. I have always wondered if Peter (the one who wielded the sword) thought to himself, “But I thought He said bring a sword!” As it is, Christ restored and healed the ear of the injured man.

The key, I think, is found in Christ’s statement to Pilate that His Kingdom is not “of” this world. That does not mean that the Kingdom is located somewhere else. Rather, it means that His Kingdom’s source is not found within the things of this world. It is a sovereign act of God. As such, its reality is independent of our actions and will. There is nothing in the Kingdom of God that requires our swords (or even our words). It is heaven-breaking-into-our-world. It is unassailable.

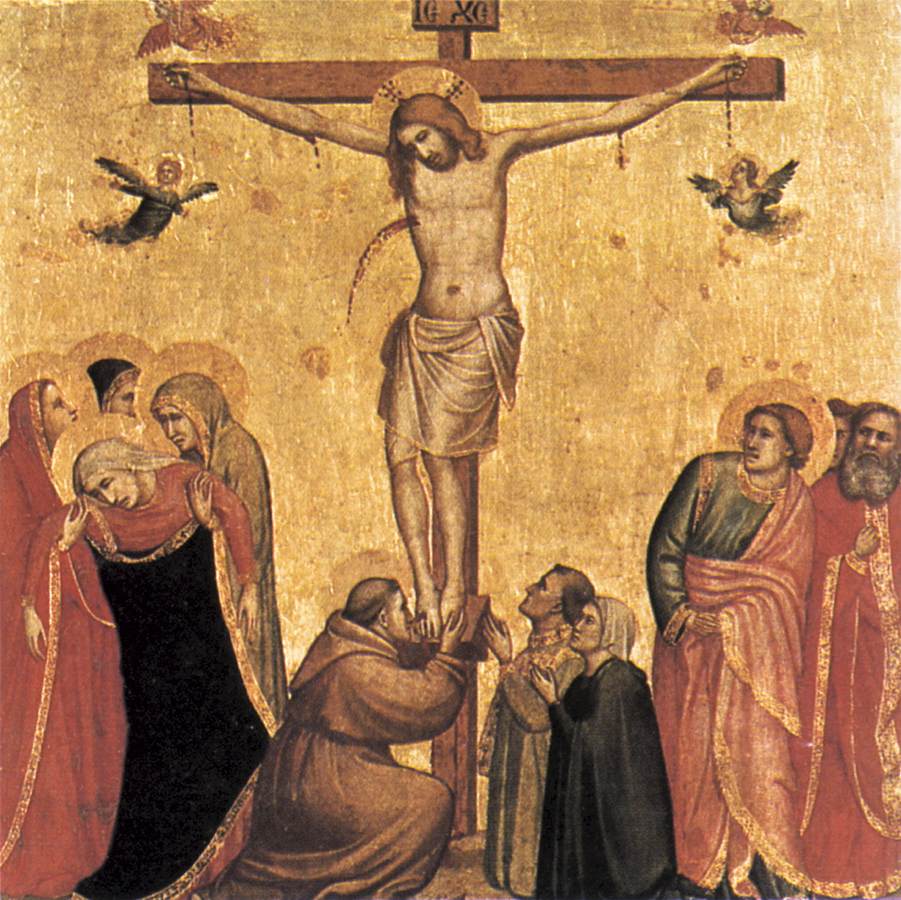

This is the faith of the martyrs. The long history of the Church’s faithful who have gone to their deaths include many stories of terrible persecutions and tortures. They also include an abiding witness to an abiding sense that everything being done to them somehow misses the point. When Christ stood before Pilate, He was threatened with the might and power of Rome. “Don’t you know I have the power to release you or to kill you?” Human beings have no power over God. The Kingdom of God willingly enters into the suffering of this world, willingly bears shame, willingly embraces the weakness of the Cross. The martyrs acted as they did because their lives were not of this world. Christians should not live in this world thinking about a world somewhere else (heaven). Rather, Christians themselves are heaven in this world. It is that reality to which we bear witness (martyr means “witness”).

Modern nation states came into existence slowly, as one of the consequences of the Reformation. Some, like England, had a head start, inasmuch as it was partially defined by its shoreline. But most, like France and Germany, evolved more slowly. We imagine today’s modern states as though they were defined by blood and language. However, that is a fantasy, little older then the 19th century. Nationalism, sadly, was one of a number of romantic movements that served to replace the common life of the Church with romantic notions of lesser, tribal belongings.

The patriotic mythologies that came into existence together with modernity’s nationalisms are siren songs that seek to create loyalties that are essentially religious in nature. World War I, in the early 20th century, was deeply revealing of the 19th century’s false ideologies. There, in the fields of France, European Christians killed one another by the millions in the name of entities that, in some cases, had existed for less than 50 years (Germany was born, more or less, in 1871). The end of that war did nothing, apparently, to awaken Christians to the madness that had been born in their midst.

I have noted, through the years, that the patriotism that inhabits the thoughts of many is a deeply protected notion, treated as a virtue in many circles. This often gives it an unexamined character, a set of feelings that do not come under scrutiny. Of course, there are other nation-based feelings and narratives, some of which are highly reactive to patriotism though they are driven as much by the passions and their own mythology. These are the sorts of passions that seem to have risen to a fever-pitch in the last decade or so, though they have been operative for a very long time.

These passions are worth careful examination, particularly as they have long been married to America’s many denominational Christianities. I think it is noteworthy that one of the most prominent 19th century American inventions was Mormonism. There, we have the case of a religious inventor (Joseph Smith) literally writing America into the Scriptures and creating an alternative, specifically American, account of Christ and salvation. It was not an accident. He was, in fact, drawing on the spirit of the Age, only more blatantly and heretically. But there are many Christians whose Christianity is no less suffused with the same sentiments.

Asking questions of these things quickly sends some heads spinning. They wonder, “Are we not supposed to love our country?” As an abstraction, no. We love people; we love the land. We owe honor to honorable things and persons. The Church prays for persons: the President, civil authorities, the armed forces. We are commanded to pray and to obey the laws as we are able in good conscience. Nothing more. St. Paul goes so far as to say that our “citizenship [politeia] is in heaven.” The assumption of many is that so long as the citizenship of earth does not conflict with the citizenship of heaven, all is fine. I would suggest that the two are always in conflict for the simple reason that one is “from above” while the other is “from below,” in the sense captured in Christ’s “my kingdom is not of this world.” There is a conflict. We should not expect that the kingdoms of this world will serve as the instrument of the Kingdom of God. Such confusions have yielded sinful actions throughout the course of the Church’s history.

St. Paul notes in Romans 13 that the state “does not bear the sword in vain.” It has an appointed role in the restraint of evil. Such a role, however, is not the instrument of righteousness. It can, at best, create a measure of tranquility (cf. the Anaphora of St. Basil). The work of the Kingdom of God cannot be coerced, nor can it be the work of coercion. It is freely embraced, even as it alone is the source of true freedom.

My purpose in offering these observations is, if possible, to “dial down” passions surrounding our thoughts of the nation and politics in order to love properly and deeply what should be loved. That this is difficult, and at times confusing, is to be expected. We live in a culture in which the passions are marketed to us in an endless stream, carefully designed for the greatest effect. If these thoughts of mine help quiet the passions to some degree, then I will have done well. If, on the other hand, they have stirred reaction, then, forgive me and let it go.

If the Kingdom of God were a ship (an image sometimes used of the Church), then we should not be surprised when the seas become boisterous and the winds become contrary. Nor should we panic if we find that Christ is asleep in the back of the boat. His sleeping, indeed, should be a clue as to what the true nature of our situation might be. There are some who imagine that the work of the Kingdom can only be fulfilled once we’ve learned to control the winds and the seas. We fail to understand that they already obey the One who sleeps.

And so we come to overcoming evil by doing good. It is a common teaching in the Fathers that evil has no substance – it only exists as a parasite. All created things are good by nature. It is the misuse of the good that we label “evil.” To do good thus has the character of eternity. It is not lost or diminished with time. Christ said, “And whoever gives one of these little ones even a cup of cold water because he is a disciple, truly, I say to you, he will by no means lose his reward.” (Matthew 10:42)

When the final account is given, the nations will not be named. Their wars and empires will pass into what is forgotten. However, the many cups of cold water and other such acts of goodness will abide. I could imagine such actions on the part of a nation, and there are probably plenty. They likely go unnoticed, or even derided as wasteful.

I think that our politics and patriotism want to measure the seas, where God is measuring cups.

Father Stephen Freeman is a priest of the Orthodox Church in America, serving as Rector of St. Anne Orthodox Church in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He is also author of Everywhere Present and the Glory to God podcast series.

Featured: Arrest of Christ, by Heinrich Hofmann; painted by 1858.