Frodo failed.

If you’re a reader of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (or just a movie-goer), then you know that the central, heroic character, the young Mr. Frodo, ring-bearer, fails to throw the Ring into the fires of Mt. Doom at the end of his arduous journey. Everything he loved, his home, his friends, every scrap of goodness, depended on the Ring being tossed into those fires, and, when it came down to it, he was unable to let it go. Fortunately for Middle Earth, the wraith-like, pitiable creature, Gollum, bit Frodo’s finger off in order to have the Ring again for his own, and accidentally slipped and fell into the fires, saving Middle Earth in the bargain. All of that drama resolved by an accident?

It is genius.

Tolkien was not writing an allegory. Things in his story do not stand for something else. Nevertheless, Tolkien’s Catholic Christianity is woven throughout Middle Earth. Tolkien believed that in Jesus Christ, all “myth” was fulfilled. The Story that every story longed to be true and anticipated in some vague sense, was incarnate and made true in the God/Man, Jesus Christ, and His death and resurrection. Middle Earth, were it to have any element of truth at all within it, were it to somehow ring true in the hearts of its readers, could not ignore the larger Story, the Great Story. Nor can we.

It has been something of a commonplace in the past number of years for writers to draw lessons, or parallels, from Tolkien’s work and the Christian story. One of my favorites is The Gospel According to Tolkien: Visions of the Kingdom in Middle Earth, by Ralph Wood, who taught at Baylor for many years and who has become a friend over the past decade or so. I frequently marvel at the insight in Tolkien’s charming tale and find my mind drifting to it as I think through various aspects of the Christian journey.

Frodo’s failure at the last moment is deeply interesting. Frequently, in our imagining of the Christian journey, the notion of failure at the last moment is appalling. We think to ourselves that a life-time of struggle can be undone in a single moment. It is, I think, a terrible caricature and diminishment of the mercy and grace of God. Our culture champions the notion of free-will and the power of choosing – as if those magical words somehow captured the whole of who we are.

Frodo’s failure is an excellent foil to this fantasy. He agreed to be the “Ring-bearer.” Through terrible sufferings and hardship, he sludges his way towards Mordor and the fires of Mount Doom. Even then, without the assistance of his friend, Sam Gamgee, he would have failed. He manages, against all odds, to stand at the very Crack of Doom, hovering over the fire. It is there that he is overpowered by the Ring itself and the malevolent will that owns it. Frodo did not “choose evil” – he was “defeated” by it. There is a world of difference.

The most astounding aspect of Frodo’s tale is the simple fact that, when all was said and done, he was standing where he was supposed to be. He had not quit.

When we proclaim, as Christians, that we are “saved by faith,” we all too easily mistake this for a proclamation about what we “think.” The simple fact is that, from day to day, what we “think” about God might waver, some days bordering or even lapsing into unbelief. The same can be said of a marriage. We love our spouse, though there might well be days that we wish we weren’t married. Faith (and love) are not words that indicate perfection or the lack of failure. “Faith,” in the Biblical sense, is perhaps better translated as “faithfulness.” Much the same can be said of love within a marriage. In both cases, it matters that we do not quit.

We cannot predict the future. The classical Western wedding vows acknowledge, “for better or worse, for richer for poorer, , in sickness and in health…” That is an honest take on life. The same is true of our life in Christ.

Modernity has nurtured the myth of progress. Whether we’re thinking of technology, our emotional well-being, or the spiritual life, we presume that general improvement is a sign of normalcy and that all things are doing well. This is odd, given the fact that aging inherently carries with it the gradual decline of health. Life is not a technological feat. It is unpredictable and surrounded by dangers – nothing about this has changed over the course of human history.

I have been an active, practicing Christian since around age 15. I have been in ordained ministry for over 43 years. Over that time, I have seen a host of Christians come and go. When I preside at the funeral of a believer (which I have done hundreds of times), I am always struck by the simple fact of completion. “I have finished the race,” St. Paul said. (2Tim. 4:7) That is no mean feat.

The most striking feature of the Twelve Apostles is their steadfastness. The gospels are filled with reminders that they frequently misunderstood Christ. They argued with Him. They tried to dissuade Him from His most important work. They complained. They jockeyed with each other for preferment and attention. Peter denied Him. Only Judas despaired. Of the others, all but one died as martyrs.

In Frodo’s tale, the final victory accomplished by the destruction of the Ring, came about both by his long struggles, but ultimately by a hand unseen throughout the novels that seemed to be at work despite the plots of Sauron. In the Scriptures we are told: “Now Moses built an altar and called its name The-Lord-My-Refuge; for with a secret hand the Lord wars with Amalek from generation to generation” (Exodus 17:16 LXX).

The hand of God is often “secret,” unseen both by us and by those who oppose us. The mystery of the Cross is easily the most prominent example of God’s secret hand. St. Paul said that the demonic powers had no idea that the Cross would accomplish their defeat (1Cor. 2:7-8).

That same hand is at work in the life of every believer. Though we stumble, He remains faithful. We cling to Christ.

There is a Eucharistic promise that seems important here: “He who eats My flesh and drinks My blood abides in Me, and I in him” (Jn. 6:56).

Father Stephen Freeman is a priest of the Orthodox Church in America, serving as Rector of St. Anne Orthodox Church in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He is also author of Everywhere Present and the Glory to God podcast series.

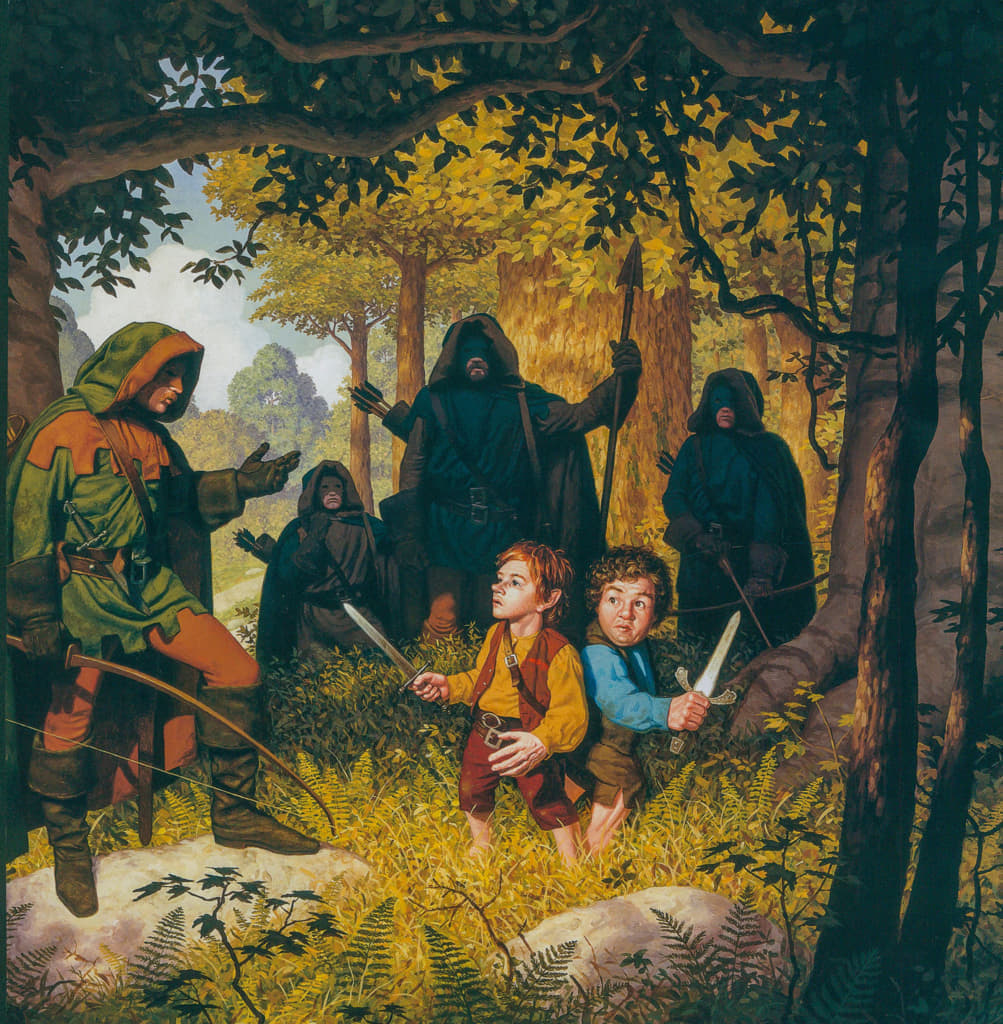

Featured: Faramir, Tolkien Calendar June 1977, by the Brothers Hildebrandt.