Your meeting with a book that became one of the most important books in life remains forever in your memory. And the writer who created that book becomes close to you, like family. Of course, this is not immediately understood, but only after the years go by. You return again and again in your memory to that day and hour when that cherished meeting took place. This happened with me when, as a student of the Urals University, I left the reading room all shaken after reading the novel, The Idiot. It seemed to me that my hair was standing on end, that my soul was as if struck, and it shook from the blow.

And so, from that same university winter, from age nineteen and for the rest of my life, the characters of Prince Myshkin, Nastasia Philippovna, Parfen Rogozhin, and others in that immortal novel entered into the very center of my heart. And later, throughout the course of my life did this novel and Dostoevsky’s fate call back to me, often determining turns in that course—at times even sharp turns.

This is what I want to tell you about today. Especially since we are in the “Year of Dostoevsky.”

Dostoevsky As A Herald Of Christ

After the second year of university, we students of the journalism school were sent for internships to the regional newspaper. I ended up in the town of Bogdanovich in Sverdlovsk province, at the newspaper called, “Flag of Victory”. I was supposed to write about the harvest, and how things stood with dairy yields. And after my ridiculous forays into the fields and dairy farms, my searches for people who were supposed to tell about the business (I could have gotten all this information over the telephone but I was “studying life”), barely alive because I either hitchhiked or used my own two feet, I flopped down on the dormitory bed to have at least a tiny rest. Then I rose early to write my reportage on the zealous work in the fields and farms.

And so, in the morning as I walked past the movie theater to the office, I saw an announcement for the film, “The Idiot”. I was stunned. All that day I only thought about getting to the theater as soon as possible to watch that film.

I watched it. And that same evening I set about writing my first review. I really regret that I didn’t save it. The editor stripped down my “creative torments” to mere notes. His conclusion was that it was “too long”. The newspaper was of a small format—culture and sports, weather, and all the rest that allowed it to pay for itself left but a small spot on the fourth column. Into that spot did they squeeze my ecstatic notes on the film. I’m sure that it must have looked crazy in that newspaper.

It was 1958; after all, the “thaw” had begun, and our dreams were swirling around something as yet unrecognized but definitely significant, and human—something pertaining not to the number of hectares of harvested wheat and rye, but to the life of the human soul.

I recall those notes because when I returned to Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg), I had something to talk with my brother about. At the time, Anatoly was studying in the acting studio at the drama theater. Of course he had read The Idiot, and we watched the film together, then discussed it vigorously. In the theater, the excellent theatrical production of The Insulted and Humiliated was on, with Boris Feodorovich Iyin, a “people’s artist of the USSR”, brilliantly playing the role of Prince Valkovsky. And the young hero, the writer Vanya, was played by our favorite actor Constantine Petrovich Maximov, Anatoly’s teacher. He knew about my brother’s passion (besides Dostoevsky, we were voraciously reading the poetry of the “Silver Age” and had even organized an “Evening of forgotten poets”).

That is why he confirmed in the role of Andrei Rublev the totally unknown provincial actor, Anatoly Solonytsin, against the opinion of the entire artistic council.

But why does Prince Myshkin touch us so deeply, even stun us with his character, his fate? Why does Feodor Dostoevsky’s hero so stir us, despite the eccentricity of his actions? One critic has aptly compared Dostoevsky’s prose with “congealed lava”. Yes, he writes in such a way that his words as if erupt from the crater of a volcano, flow rapidly down the slope, wiping out everything on their path, and then congeal before our eyes, in our souls. The “golden pens” of the Russian literati, such as Turgenev and Bunin, even accused Feodor Mikhailovich of chaotic and sloppy writing.

Yes, Dostoevsky’s prose really was “unpolished”, as the author himself has said. But that is what makes it so remarkable and unique—its force and impetus. His characters are taken into “borderline” situations, when the “major” issues of life, as the author put it, are in the balance—into man’s existence in general.

Can a person in such moments of life talk without “choking on his own words”, in separate phrases? Moreover his heroes get entangled, and the entanglement comes from the fact that Dostoevsky is not afraid to show man’s “duplicity”, digging down at times to the most hidden depths of the soul. That is why his heroes say one thing but mean something entirely different, twist their way out of it and lie, while Prince Myshkin’s openness and childlike ingenuousness exposes them.

Just as do the exceedingly bold and “reckless” acts of Nastasya Filippovna.

Recall how she throws the bundle of 100,000 rubles Rogozhin brought into burning fireplace. One researcher of Dostoevsky’s works figured out that 100,000 rubles in Dostoevsky’s time would equal over a million USD today.

In the 1960s, out of romanticism I left for Kaliningrad to get a job on the whaling ship, the “Yuri Dolgoruki”. Because I was considered “unreliable” and therefore not someone who could be let out of the country, they didn’t take me out to sea. But I wrote my first stories about sailors “ashore”, and published my first book, with which I was accepted into the Soviet Writers’ Union. This took place at a meeting of young authors of the Northwest in Leningrad. There I saw the famous stage presentation of “The Idiot” with Innokenty Smoktunovsky in the main role.

I am not the only one who was stunned by the show. All who saw how Smoktunovsky played his role understood that a miracle was happening before their eyes. His Myshkin was naïve like a child, open, defenseless—and at the same time protected by the truth of Christ the Savior. It could even be that the actor did not understand that he was embodying on the stage a blessed one, whom everyone around him took for an idiot. Nor did the theater understand this. Years later, just before his death, on a lengthy television program the actor related that he roused the entire theater against himself because he continued to shape the role differently from how everyone—from the chief director down—was telling him to do it. He did it according to his heart’s urgings. The show’s premier was scheduled for December 31. It was four hours long. G. Tovstonogov was prepared for a failure, and that is why the premier was scheduled for New Year’s Eve.

For the first time in many years, the theater was half empty. But on January 1, news spread throughout Leningrad that in the Great Drama Theater a miracle had taken place. Then it became simply impossible to get a ticket. Because on that stage, for the first time in nearly century of godless rule, people saw authenticity of feeling, not human but divine truth, which shown in the actor’s eyes, in his inimitable intonation as he pronounced words about faith, love, and God. And the souls of all present in the theater opened up, empathized, wept, and laughed together with him.

Here is what Prince Myshkin says when Parfen Rogozhin asks him whether or not he believes in God:

“An hour ago, as I was returning to the hotel, I ran into peasant woman with her infant. The woman was still young, and the babe would have been about six weeks old. The child smiled at her, as she observed, for the first time since she was born. I looked, and the woman very, very piously, suddenly crossed herself. “What’s that, young lass?” I said (for I asked her about everything then). Well, she said it’s maternal joy for seeing her infant smile at her for the first time; for God has the same joy when He sees from heaven how a sinner starts praying to him with his whole heart for the first time. That is what the woman said to me in almost those exact words; and such a profound, such a subtle and truly religious thought, a thought in which the whole essence of Christianity is expressed in a moment; that is, the whole understanding of God as our own father… It’s a most important thought about Christ! A simple peasant woman!.. Listen, Parfen, you asked me just now and here is my answer: The essence of religious feeling doesn’t fit into any sort of discussion, any actions or crimes, any kind of atheism. Something is amiss there, and it will be that way for eternity. There is something on which atheism will forever slip up and miss the point. But the main thing is that you’ll most probably and clearly notice this “something” in the Russian heart—and that is my conclusion!”

When the show was over, for two or three minutes there was a sepulchral silence. Then the auditorium exploded in applause, shouts, and in such a pervading stormy ecstasy that’s hard to describe. This went on for twenty to thirty minutes. I was told that there were times when it lasted even longer. As the years passed, critics both in Russia and abroad (the presentation played also in London) understood that an event had taken place that was so huge, on a scale so significant that it’s hard to express in words. Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky stood before the people—alive, authentic, the man who is rightfully called a Russian genius.

The role of Prince Myshkin, I think, was the one for which actor Innokenty Mikhailovich Smoktunovsky was born. He played about a hundred roles in the movies. He acted in many good, even excellent theater productions. But none of them reached the heights of Prince Myshkin. The actor did not act, but lived on the stage the life, I repeat, of a man of God. He was also like that in real life—strange, and unfathomable for many. And in his best roles in both theater and film are heard those familiar intonations of Prince Myshkin—pauses, expressions of the eyes, gestures—of a man who is not of this world.

The [communist] party leadership also felt this, and that is why the performance was never videotaped. Only small snippets were saved for programs. Thank God, it was at least preserved on vinyl record disks, and a three-volume album was made available.

I still have my old “music center”, and favorite records. From time to time I listen to the recording of that amazing show, which during atheistic times told of a man who sacrificed his own life for the sake of his love of God and people.

What did Feodor Dostoevsky write about in his immortal novel?

To Guess At The Mystery

In a letter to his brother Mikhail, the seventeen-year-old Dostoevsky wrote:

“Man is a mystery. It must be unraveled, and even if you’ve spent you whole life unraveling it, you can’t say that you’ve wasted time. I am occupied with this mystery, for I want to be a man.”

That is how the young Feodor determined the purposed of his life even before he’d written his first short story, Poor Folk, which Belinsky read and then exclaimed ecstatically, “A new Gogol has appeared!”

Feodor Mikhailovich felt with his heart his purpose in life. It is important to determine this purpose, or it would be better to say, calling, which is the meaning of your life. It is important not to betray it, but to walk what is often a thorny path, but a path that calls to you to follow the call of your soul. I don’t in any way want to compare the scope of the great writer’s gifts with those directors and actors who had the fortitude to play and produce the author’s works in theater and film. But the yearning to express in their creative work the hidden mystery that is embedded in his great novels, remains the cherished dream of many. This would include such film producers as Andrei Arsenievich Tarkovsky. After his films, “Ivan’s Childhood” and “Andrei Rublev”, which brought him international fame, he wrote an expansive proposal for the screening of “The Idiot.” An anniversary date was approaching—in 1981 it was proposed to have a grand celebration of the one hundred years since Dostoevsky’s death, and 160 years since his birth. Tarkovsky had the idea of filming a television series. In his diaries he wrote, “Solonitsyn would be ideal for the role of Dostoevsky.” In his proposal he determined that the author of the novel, i.e., Dostoevsky, should play the role of the narrator. This actor, Anatoly, was entrusted with the role of Lebedev—that very liar who swears his love for the “excellent prince” but at the same time writes an “exposé” about him. Myshkin was to be played by Alexander Kaidanovsky, and Nastasia Filipovna by Margarita Terekhova. My brother and I were transported when talked about the work ahead. Anatoly was even ready to have plastic surgery in order to look more like his favorite author.

“How are you going to play other roles if you undergo such surgery?” Tarkovsky asked him.

“Why would I need any other roles, if I’ve played Dostoevsky?” my brother answered.

The surgery never happened, because Tarkovsky’s proposal was rejected. But Anatoly would yet experience the happiness of embodying the great writer’s image on screen—albeit in a film of a completely different scale.

The film was called, “26 Days in the Life of Dostoevky”.

I’ll tell you in a little more detail why in that memorable time an amazing “coincidence”, as it would seem at first glance, took place.

Anatoly was forty-five years old—just like his hero when in 1866 he dictated the novel, The Gambler (to a stenographer). Like his hero, after a family catastrophe Anatoly had proposed to a girl who was half his age. Like his hero, Anatoly’s love was requited—and she transformed the entire rest of his life.

And hadn’t Anatoly also worked under similar circumstances?

“Well, the novel will have to be rushed by post-horses”, Feodor Mikhailovich said to Anna Grigorievna [his stenographer and future wife].

And the film was also shot as if by “post-horse”. Anatoly was under pressure to make a down payment on a cooperative apartment, and he was in debt up to his ears.

When I arrived in Moscow and met with my brother, I read the scenario and told him about all this.

He smiled, “Do you think they know about this? They hired me as a serious and reliable professional, and that’s all.”

But in fact they didn’t just “hire” him so simply. N. T. Sizov, director of Mosfilm at the time, summoned Anatoly and asked him to help the group of “26 Days in the Life of Dostoevsky”. “People’s Artist of the USSR” Oleg Borisov, who was playing the leading role, had just left the group. Half of the film had already been shot, but the creative formats of the director and the actor, different from the very beginning, had now irreversibly diverged. My brother could not bring himself to refuse the requests of the general director, who had shown both attention and care towards the actor, and of the producer, who had produced Anatoly’s favorite films from childhood on. Anatoly knew that the picture would be filmed under tough deadlines—a plan is a plan, and cinema is also a production line. But as an actor, Anatoly always needed time to “rev up”, time to take on his role. Anatoly was also dissatisfied with much of the screenplay. But after all, we’re talking about Dostoevsky!

“I don’t have enough time… You see, I’m living in a hotel across the street from Mosfilm. We’re punching two shifts in a row… It’s an endless race… You know, the only thing that seems not so bad to me so far … One scene… Where he’s with students, where Anna has taken him. He talks about hard labor in prison, and argues with the youths… And then he has an epileptic fit… Only don’t tell anyone this, understand? (He always began with these words whenever he wanted to tell me something important.) Do you understand, they started applauding. The entire group… That’s not acceptable in filmmaking, it’s sort of against the rules of decency. But they applauded, and Zarkhi didn’t criticize anyone for it. Then another double, and again applause. It’s stupid of course. The guys explained that they couldn’t help it. Well, there you are, I’m boasting… But even without the applause I feel that the scene was successful.”

But that very episode was cut from the film—it supposedly “didn’t reflect the writer’s character.”

Our bureaucrats “of art”, as if they had a mine detector in their hands, always find the very best scenes or pages in books, which they simply must “delete as extraneous”. And this applies not only to the past—even today these “mine detectors” are still in their hands for some reason.

Nevertheless, the film was successful not only in our own country but also on the international level. It represented our film industry at the thirty-first International Film Festival in Western Berlin. Here is what the papers wrote:

“Outstanding in the film was the role by Anatoly Solonitsyn. In conjunction with the sincere ingenuousness of Evgenia Simonova, it all together gives us a glimpse into the creative mystery of those literary works of genius, and into the character of a great man who inspired the whole world’s admiration… (Die Welt).

There is no point in comparing the performances of actors in films and plays in which they played the same roles. Different times determine differently both the position of the producers and, correspondingly, the role of the actors. But there are “breakthroughs”, when the performer of the leading role refuses to conform himself to the will of circumstances, producers, or even collective opinion, and does not waiver from the path leading to understanding a man’s mystery.

So it was with Innokenty Smoktunovsky, who wouldn’t heed the “vulgar” advice of famous actors and a no less famous director, as he expressed it in the foregoing story I’ve told you concerning the play, “The Idiot”. He walked a torturous path to the hidden mystery of the man whom Dostoevsky named, Prince Myshkin.

So also was it with Anatoly Solonitsyn, who against all circumstances, both mundane and creative, was able by force of his God-given talent to break through to the secret of that author, who lived and created to the glory of God.

Alexei Solonitsyn is a prominent Russian actor and film script-writer. This article appears courtesy of Pravoslavie.

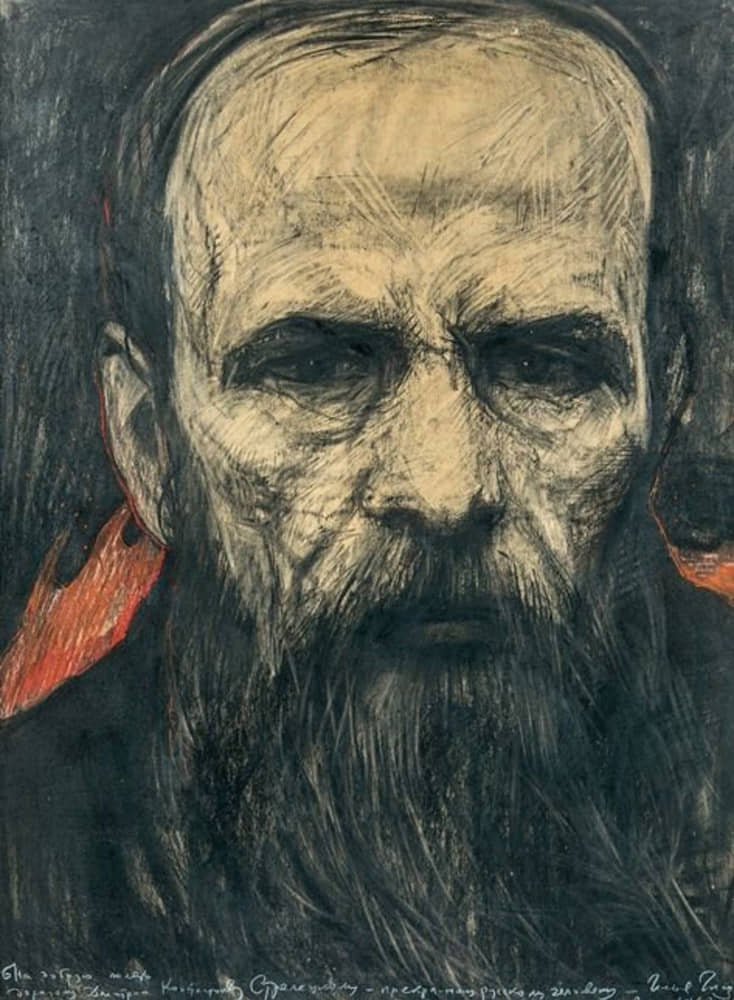

The featured image shows a portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky, by Ilya Glazunov; painted in 1968.