If, after plodding through page after dense page of some philosophic text, say, Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, or Schopenhauer’s expanded 1844 version of The World as Will and Representation, you find yourself wondering bitterly why philosophers can’t seem to express their views in a more condensed and lively fashion, or—even more heretically—why philosophers tend to be such, well… tedious personages with no sense of humour and such boring lives, you simply haven’t come across Vladimir Solovyov (1853-1900).

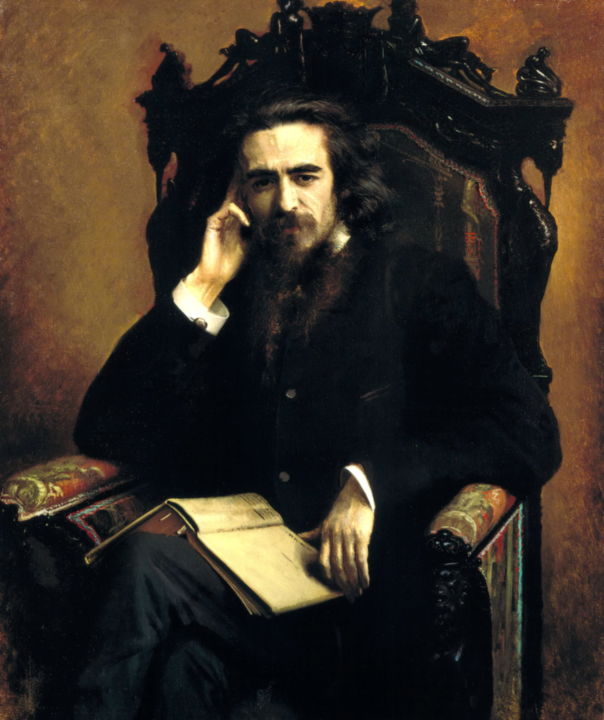

Solovyov (his last name has been transliterated into English in a variety of ways) was a philosophical and literary heavyweight in 19th-century Russia, whose views on contemporary life were eagerly sought out by the press, and whose ideas had an enormous impact not only on other Russian philosophers, but also on such giants of Russian literature as Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (Solovyov became close friends with the latter in the late 1870s), and on the entire movement of the Russian Symbolist poets.

Solovyov is still largely unknown in the West, though lately he has been more prominent on the Western cultural radar, due to the efforts of such scholars and translators as Judith Deutsch Kornblatt.

Solovyov was born in Moscow, into a devoutly Orthodox family of well-known intellectuals—his father was an eminent historian and a rector of Moscow University, and his many siblings included writers, poets, and artists.

Solovyov had a spiritual bent as a young child (he used to throw off his bedcovers and shiver “for the glory of the Lord”) and loved imaginative games.

In his early teens, he became a trouble-maker and hell-raiser, impersonating the Antichrist to frighten the peasants at the family country estate.

Around that time, he experienced a crisis of faith that lasted until his early university years, during which he enraged his usually placid father by throwing the icons out of his bedroom.

Throughout it all, he remained an excellent student and finished school with a gold medal, after which he enrolled at the University of Moscow. He vacillated between the Historical and Philological Faculty and the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics, finally graduating from the former in 1873.

His ultimate choice was apparently influenced by a chance encounter with a young woman on a train, during which he experienced a vision of a spiritual entity in female form that reminded him of a similar vision that he had had as a child.

He identified his vision as the glorious revelation of Sophia—the Eternal Feminine—Divine Wisdom—Hokhmah, as she is known in various esoteric traditions.

Profoundly shaken and inspired to re-connect with his Orthodox heritage, Solovyov moved to the district of Sergiev Posad, close to the famous male monastery, and audited courses offered at the Moscow Theological Academy (where the Russian Orthodox Church educated its priests and theological scholars).

Solovyov went on to write a thesis for a Master of Philosophy degree, titled The Crisis of Western Philosophy Against the Positivists, (1874), in which he criticised Western philosophy as an artifact that had outlived its usefulness, attacked Positivists from a Slavophile position, and argued for a new synthesis based on religious principles.

The defense of the thesis in St. Petersburg generated a spirited debate in the press, attracting the attention of Leo Tolstoy, among others. After the defense, he was invited to remain at the Historical and Philological Faculty as a Docent, the equivalent of an assistant professor, to deliver a series of lectures at the University of Moscow, and to give lectures at the famous Moscow Courses for Women.

Although he was enthusiastic about taking up his duties as a Docent, he soon applied to do research in London’s British Museum, in order to study Indian, Gnostic, and Medieval philosophy.

In London, Solovyov studied the Kabbalah and various occult subjects (despite his mystical yearnings he was level-headed enough to recognize that Spiritism, to which he was introduced in London, was utter quackery).

After experiencing another ecstatic vision of the Sophia in the Museum, he abruptly decided to travel to Egypt, where he claimed he experienced yet another revelation of Sophia in the desert.

He lived in Italy and France for a while, and then returned to Russia. He resumed his duties at the University of Moscow, but then got fed-up with university politics and moved to St. Petersburg in 1877.

There, he became a member of the Learned Committee in the Ministry of National Education (he characterized the meetings he attended as “deadly boring and endlessly stupid, but, thankfully, infrequent”); he also lectured at the University of St. Petersburg, while writing his PhD thesis.

It was in St. Petersburg that Solovyov became close friends with Fyodor Dostoevsky, who would base the character of at least one of the Karamazov brothers on Solovyov (Dostoevsky’s widow felt that the subtle thinker Ivan Karamazov was modeled on Solovyov, and there is a persistent tradition that the earnest and boyish Alyosha Karmazov was also inspired by him).

In 1880, Solovyov defended his doctoral thesis titled The Critique of Abstract Principles, in which he continued his critique of the western philosophical traditions and argued that the real goal of philosophy is to define the meaning of human life and human activity, which it can do only after it determines the nature of existing reality.

He delivered and published a number of important lectures, including his Lectures on Godmanhood (1878-1881)—attended by Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and other notables. He continued as a Docent rather than as a full professor, because his relationship with the Dean of the university soured for a variety of reasons.

He had to leave academia entirely after the assassination of Alexander II, when he gave a speech arguing that Alexander III should show Christian forgiveness and mercy to the murderers of his father, commuting death penalties for exile in Siberia.

After leaving academia, Solovyov finally spread his wings as a philosopher and a writer, writing countless articles in the main journals of the day, travelling, giving public lectures, publishing a number of seminal works—some of them in French—about the ultimate destiny of Russia and mankind.

These included: Russia and the Universal Church [1889]; The General Meaning of Art [1990]; The Meaning of Love [1894]—which inspired Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata; The Spiritual Foundations of Life [1897]; Three Conversations about War, Progress and the End of World History [1900]; Tale of the Antichrist [1900].

Uncharacteristically for a philosopher, almost all of these works are highly readable, possibly because many of them originated as lectures and retain the gesture of the spoken word, and also because Solovyov had a pronounced sense of humour.

In fact, Solovyov began one of his first lectures by defining man not as a “social creature but as a laughing creature”—and all his friends testify in their memoirs that he loved to laugh and that he laughed at every opportunity.

His ability to poke fun not only at the things he held precious but at himself is probably one of his most endearing characteristics. Here, for instance, is a joking epitaph that he wrote for himself:

Vladimir Solovyov lies buried in this spot.

Once a philosopher, now he is nought.

Well-liked by some, by others held a foe,

Died in a gorge—mad love has laid him low!

He lost his body and his soul as well.

Dogs ate the former—the latter is in hell…

Oh Passerby, learn well from his wraith,

Of the banefulness of love and the benefits of faith.

(1892; trans. Maria Bloshteyn)

If one had to summarize Solovyov’s beliefs, one could say that he was a mystical optimist, with a firm faith in the imminent arrival of God’s Kingdom, and a no-less firm belief in Russia’s special destiny in bringing God’s Kingdom to the rest of humanity.

The specifics of his ideas were considerably more controversial, and drew the ire of Russians from many different camps. For example, one of his key beliefs was the need for the global unification of the church.

Solovyov regarded the Russian Orthodox Church’s dispute with the Roman Catholic Church as a rift that must be healed (there were persistent rumours that he himself converted to Catholicism)—an idea not welcomed by the Russian Orthodox Church to this day.

He also felt that there was an impending mega-war (possibly correlated with the Gog and Magog war which the Bible promises will occur at the end of days), during which the nations of Europe will have to join up with Russia in order to defend themselves from the Pan-Mongolians.

Unfortunately, that particular idea was accompanied by obnoxious racist attitudes, whereby the Chinese and the Japanese were viewed as the evil non-Christian “Yellow Peril,” who were about to conquer Europe and rule it mercilessly, until the Europeans (and Russians) would join forces, rise up, overthrow the invaders and begin a new harmonious era of world history.

But all these ideas were almost incidental to the main one: His belief in the Divine Sophia, the manifestation of highest Divinity, mankind’s ultimate future, around which all his other ideas revolved. (Parenthetically, the Russian Orthodox Church rejected Solovyov’s notion of the Divine Sophia and declared it heretical).

It was in Sophiology, as Solovyov called it, that he strove to bring together empiricism, rationalism, and mysticism into one grand over-arching system.

Notably, Solovyov’s key philosophic vision was actually expressed by him not in a weighty treatise, but in a long and humorous—although also seriously intended—poem, which is usually translated as “Three Meetings” or “Three Encounters,” but is much more accurately rendered as “Three Rendezvous.”

The Russian word Solovyov uses both for the title and when he describes waiting in Egypt for a sign from Sophia that she is willing to reveal herself to him is svidanie—a rendezvous or even a lovers’ tryst.

There is nothing new about depicting God as the beloved, but when Godhood is envisioned as a woman, a desired woman, no less, a tension arises between the metaphysical and the sensual, which Solovyov explores (and occasionally exploits) in his poem.

He refers to Sophia as his podruga, which can either mean (girl)friend, or beloved/lover. His demands to be shown the “whole of her,” and his insistence that he will not be denied, also acquire a lover’s—not a worshipper’s—urgency.

Lastly, in the author’s note that he appends after the poem, he coyly states that it has appealed to “some poets and some ladies,” seemingly negating the poem’s metaphysical thrust.

Judith Deutsch Kornblatt writes about his “audacious combination of humor and mysticism, of sexuality and sacred vision, of fiction and spiritual truth.” All these are evident in “Three Rendezvous,” a poem that remains both one of Solovyov’s most accessible expressions of his beliefs, and the heart of his philosophic legacy (and poetic legacy as well—the Russian Symbolists adopted Solovyov’s symbol of the Divine Sophia in their many poems and adapted it to their needs, which Solovyov did not appreciate).

Solovyov died at 47. He never married, but he did have a number of strong and passionate attachments mostly, as it turns out, to women named Sophia. He never had a proper home—he stayed with various friends. He was always sickly, but especially so during the last decade of his life.

His visions included much more terrifying subjects than the Divine Sophia: once, while travelling on a boat around Easter time, Solovyov walked into his cabin only to discover a devil sitting in a corner of the room.

Petrified, Solovyov stammered, “Don’t you know that Christ has risen?” The infuriated devil replied, “Maybe He’s risen, but I’ll get you anyway!” and attacked Solovyov.

The two fought. Solovyov passed out and was discovered only much later, flat on his back.

After this incident, he started to douse himself and his immediate surroundings with turpentine, believing that it kept devils at bay. This liberal and unorthodox use of turpentine is said to be one of the causes of his early death (he was also severely undernourished).

Despite his untimely demise, Solovyov and his legend live on in Russian philosophy and Russian poetry: A thinker, a visionary, a man with a great sense of humour and a great many biases, a poet and a seeker.

Internationally, Solovyov is remembered for his willingness to reach across religious boundaries and to build roads between entrenched and hostile camps (surely something of lasting relevance).

The late Pope John Paul II called him, “one of the greatest Russian Christian philosophers of the 19th and 20th centuries.”

As a personality, Solovyov struck everyone he met by his earnestness and his openness (traits that attracted Dostoevsky and Tolstoy to him even more than his ideas).

What continues to inspire Solovyov’s readers most is his desire to find the truth, his willingness to search for this truth alone, if need be, and his conviction that eventually the truth will be found, as he wrote in one of his most thrilling poems:

Through morning mist, with steps uncertain,

I set my course to mystic, wondrous shores.

Dawn battled with the last few stars,

Dreams hovered still—and, grasped by dreams,

My soul said prayers to unknown gods.

This cold white day, along a lonely road,

I walk, just as before, across an unknown land.

The mist has lifted and my eyes see clearly

How arduous the alpine track–how distant,

How very distant are the dreams I’ve dreamt.

And unto midnight, with firm steps,

I will keep striding toward longed-for shores,

Where on a mountaintop, beneath new stars,

Ablaze all over with triumphant lights,

My cherished temple stands awaiting me.

(trans. Maria Bloshteyn)