We often hear about alleged polytheism in Arabia during pre-islamic times, the so-called ǧāhilīya, which was seemingly filled with mušrik practicing various forms of širk in honour of various deities. Naturally, this Arabic root does not refer to a plurality of deities, but rather to “partnering” or associating others with Allah who is unique (tawḥīd)—it is a polemic reference to the Christian notion of the Trinity, in which Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost also participate equally (šarika) in the Godhead.

The question is to what extent polytheism still persisted in the Greco-Roman Middle East of Late Antiquity, which, as was the case with the Roman Empire in general, seems largely to have been permeated by monotheistic traditions before the seventh century. The Qur’an would seem to support this notion—it is (un)surprisingly vague in this regard. In the alleged Satanic Verses (53,19-20), “Have you thought of al-Lāt and al-‹ Uzza and Manāt, the third, the other?” we find a vague reference to three pan-Semitic goddesses, who were venerated by many peoples in many places at many times. The only other concrete reference is 71, 23: “And they say: Forsake not your gods, nor forsake Wadd, nor Suwa’, nor Yaghuth and Ya’uq and Nasr,” the gods of those condemned to perish in the Deluge (cf. Gen 7,24-8,14).

The mention of these five deities of antediluvian times, and allegedly worshipped by Arab tribes until the arrival of Islam, understandably caused some unpleasant difficulties for later Islamic exegetes, not to mention the modern reader—how can the knowledge or the cult of them have survived that global eradication? According to Ibn al-Kalbī’s Book of Idols (Kitāb al-Aṣnām), a compendium of legends and not an historical source, they are said to have washed up on the beach of Jeddah (the nearest port city from Mecca) after the Flood, where they gradually silted up until the fortune teller Amr ibn Luhai was told their location by his demon Abu Ṯumāna.

Be this as it may, we must remember that the Quranic account is based on (see above) the biblical one, which in turn, probably during the Captivity, was derived from Mesopotamian myths (e.g., the Atraḫasis epic, and the reworking of this narrative in the Twelve Tablet version of the Gilgamesh Epic): in the Mesopotamian version, the myth serves to explain why humans die, and does not function, as in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition, as a divine punishment for otherwise unspecified sins. In Mesopotamia (lit. “Land between rivers”), inundations were rather commonplace, in contrast to Israel or more to the point, the arid Hijaz (and we note here in passing, that the Greek flood story around Deucalion also has a Semitic background [cf. Lucian, De dea Syria 13], cf. Iapetós of the “Catalogue of Women,” attributed to Hesiod, probably has something to do with the son of Noah, Japheth, Gen 10,2 ).

In any case, these Quranic deities are unknown in Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian literatures. Their mention here remains Delphic, as has been noted in the past, e.g.: “Why Muhammad lists five deities as Noahite in Sur. 71,22ff. cannot be explained” (Fr. Buhl, Das Leben Muhammeds, reprint Hildesheim 1955, 74). “Admittedly, they must have been rather insignificant local deities at that time and in Mecca only known by name, if Muhammed can put them into the pre-Flood times” (J. Wellhausen, Reste arabischen Heidentums, reprint Berlin 1961, 13).

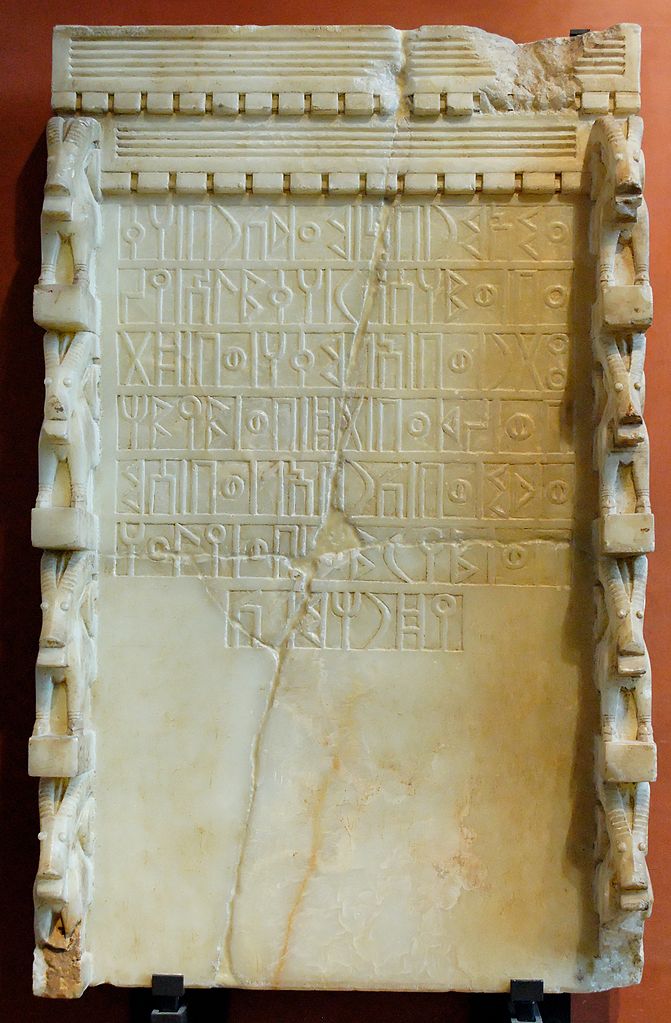

The first god mentioned in this Quranic verse, Wadd, i.e., “beloved” in the non-sexual sense (wdd – therefore probably more of an epithet than a divine given name) is known from numerous inscriptions as the chief god of the Minaeans, a Yemeni kingdom which especially during the last centuries before Christ dominated trade along the incense route, eventually being subjugated by the Sabaeans after the campaign of Aelius Gallus in 25/24 BC. At first sight, we are dealing with an authentic old-Arabian god, which could indeed have been worshipped in the Hijaz. However, epigraphic finds are by no means limited to Ma‛īn, but is, as is to be expected with such a trading empire, spread further beyond the actual homeland. So, for example, a bilingual Greco-Minaean inscription on a marble altar was found on the Greek island of Delos, dated to after 166 BC, which mentions this deity in both languages:

Minaean (RÉS 3570)

1) Ḥnʾ w-Zydʾl ḏy Ḫḏb Ḥnʾ and Zydʾl, the two of the tribe Ḫḏb,

2) nṣb mḏbḥ Wdm w-ʾlʾlt built this altar to the Wdm and the gods

3) Mʿn b-Dlṯ of Maʿīn on Delos.

Greek (ID 2320)

Ὄδδου [Belonging to] Oaddos/Wadd

θεοῦ the god

Μιναίων of the Minaeans

Ὀάδδῳ [Dedicated to} Oaddos/Wadd.

This find alone makes it clear that the cult of this god, or rather this divine epithet, although certainly originating in Yemen (which is not a synonym with Hijaz, but an entirely different culture), had travelled far beyond, accompanying his worshippers on their mercantile journeys. We thus have a deity that on the one hand was not originally at home in the Hijaz, but could have been brought there sometime by Minaean traders; on the other, however, as with the three goddesses mentioned above, he attracted some following in a geographically vast region.

As for the second deity, Suwāʿ our only sources are contradictory reports from later Islamic traditions, some of which mention him, others which do not (e.g. Wāqidī mentions the destruction of his idol in Mecca, but this is not mentioned in the Prophet’s hagiography by Ibn Isḥāq)—”these stories of the destruction of the idols on behalf of Mohammad become more and more complete as the tradition moves further away from its origin, and the narratives are contradictory” (Wellhausen, op. cit. 19). Apart from such historically worthless information and some possible attestations as a theophoric element in early Islamic onomastics, we know literally nothing at all about this god. Did he even exist? I rather have the impression that there is a polemical intention behind this name, cf. Syriac šū/ōʿā (šwʿ >arab. swʿ) “stone, rock,” i.e., “petrified,” in the sense of a stone idol (Arab. waṯan, a loan-word from Sabaean, where the word has the meaning “boundary stone, stele”), which later was misunderstood not as a generic term for an idol, but rather as the name of a specific idol.

As for the third of the three here, Jaġūṯ, we again find colourful discrepant and paradoxical stories in the Islamic tradition. But as Jaġūṯ in Arabic means “he who helps—the helper” (possibly related to Jeush in Gen 36,14), this term is rather an epithet that could be applied to any (benevolent) god. Even if the Islamic tradition(s) actually contain(s) authentic materials here and there, it would be impossible to determine whether one and the same deity was meant in all cases.

The fourth God supposedly revered by Noah’s contemporaries according to the Qur’an, Jaʿūq remains shrouded in even more mystery than his already mentioned partners. There is no independent evidence for this god, and even his name does not seem to be Arabic. Wellhausen, who noted (op. cit. 23) “we are dealing with a South Arabian name,” thought of the closely related Ethiopian verb jǝʿuq (basic meaning “to observe, to be careful, to preserve; to manifest (reveal)”), although this root seems to be not of Semitic but rather of Cushitic origin, i.e., an African loan word in the Ethiosemitic languages.

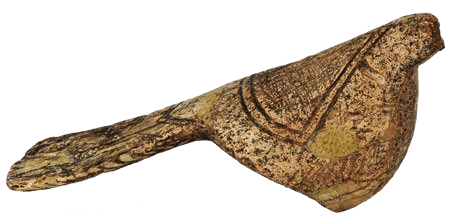

Our findings up till now are somewhat meagre, even antediluvian with regard to what we actually know. It is thus of some relief that about the fifth god, Nasr, we actually have some data. In modern Arabic this word means “vulture” (perhaps originally denoting a totem animal). In the Talmudic treatise Avoda sara 11b, in a discourse on idolatry, we find the assertion:

אמר רב חנן בר רב חסדא אמר רב ואמרי לה א”ר חנן בר רבא אמר רב חמשה בתי עבודת כוכבים קבועין הן אלו הן בית בל בבבל בית נבו בכורסי תרעתא שבמפג צריפא שבאשקלון נשרא שבערביא

“Rav Ḥanan bar Rav Ḥisda says that Rav says, and some say that it was Rav Ḥanan bar Rava who says that Rav says: There are five established temples of idol worship, and they are: The temple of Bel in Babylonia; the temple of Nebo in the city of Khursei; the temple of Tirata, which is located in the city of Mapag; Tzerifa, which is located in Ashkelon; and Nashra, which is located in Arabia.”

This passage in turn is reminiscent of one found in the famous Doctrina of the Apostle Addai (Phillips edition, p.23f.):

ܿܡܢܘ ܗܢܐ ܢ ܼܒܘ ܦܬܟܪܐ ܥܒܝܕܐ ܕܣܓܕܝܢ ܐܢܬܘܢ ܠܗ܃ ܘܒܝܠ ܕܡܝܩܪܝܢ ܐܢܬܘܢ ܠܗ܂ ܗܐ ܓܝܪ ܐܝܬ ܒܟܘܢ ܕܣܓܕܝܢ ܠܒܪܬ

ܢܝܟܠ ܐܝܟ ܚܪ̈ܢܝܐ ܫ ̈ܒܒܝܟܘܢ܂ ܘܠ ܼܬܪܥܬ ܼܐ ܐܝܟ ܡ ̈ܒܓܝܐ܂ ܘܠܢܫܪܐ ܐܝܟ ܥܪ̈ܒܝܐ܂ ܘܠܫܡܫܐ ܘܠܣܗܪ ܼܐ ܐܝܟ ܫܪܟܐ ܕܚܪ̈ܢܐ ܼ

ܕܐܟܘܬܟܘܢ܂ܠܐܬܫܬܒܘܢܒܙܠܝ̈ܩܐܕܢܗܝܪ̈ܿܐ܂ܘܒܟܘܟܒܬܐܕܨܡܚܐ܂ܠܝܛܗܘܓܝܪܩܕܡܐܠܗܿܐ܂ܟܘܠܿܡܢܕܣܿܓܕ ܼ

ܠܒܪ̈ܝܬܐ܂ ܐܦܢ ܓܝܪ ܐܝܬ ܒܗܝܢ ܒܒܪ̈ܝܬܐ ܕܐܝܟ ܪܘܪ̈ܒܢ ܡܢ ܚܒܪ̈ܬܗܝܢ܂ ܐܠܐ ܟܢ ̈ܘܬܐ ̈ܐܢܝܢ ܕܚܒܪ̈ܬܗܝܢ ܐܝܟ ܕܐ ܿܡܪܬ ܼ

ܠܟܘܢ܂ܟܐܒܐܗܘܓܝܪܡܪܝܪܐܗܢܐܕܠܝܬܠܗܐܣܝܘܬ ܿܐ܂

“Meanwhile, I saw this city teeming with paganism, which is against God. Who is this Nabû, [but] an idol [made by men] whom you worship, and Bêl whom you worship? Behold, there are among you people those who worship Bath Nikkal such as the people of Harran, your neighbours, and Taratha [as venerated by] the people of Mabug, and Nashara by the Arabs, or as are the Sun and the Moon worshipped by the rest of Harran, as you do too. Do not be deceived by rays of light and by the bright star, for all creatures will be cursed by God.”

Nabû was a well-known Mesopotamian god of the first millennium BC (the son and quasi successor of Marduk, whose name means “the announcer, the called one”—cf. Nebuchadnezzar, Nabī “prophet”); Bêl is the Mesopotamian, and later Aramaic realisation of Baal, whose cult was well-known, i.a. at Palmyra; Bath Nikkal (“the daughter of N.”)—Nikkal is a goddess known in the Western Semitic world and among the Hurrians (derived < Sumerian NIN.GAL “great mistress”); the Sun and Moon, resp. Shamash and Sîn were naturally also worshipped in Mesopotamia as deities. Taratha is apparently another designation of the well-known goddess, Atargatis or the Dea Syria, who was worshipped at Ashkelon (cf. Diodorus Siculus, Library, II.iv.2, where, among other things, it is described how and why she took the form of a fish—cf. the fish symbolism in Christianity: ΙΧΘΥΣ). Of particular significance is the fact that Nashara is also regarded here as a god of the Arabs. This god is particularly well known among the Mandaeans in southern Mesopotamia and in Iran (e.g., the Mandaean Great Book of John, §73), and also attested by Jacob of Serug (451-521), who reports that the Persians were tempted by the devil to create an “eagle” (Nashara) as an idol. A similar account can be found in the Armenian History by Movses Khorenatsi (where the gods are called Naboc’us, Belus, Bathnicalus and Tharatha).

In all of these cases, including Qur’an 71,23 (supra), we are dealing with a formulaic warning against apostasy, that is to say against a falling away from the true faith in the one true (Jewish, Christian, Mandaean or Islamic understanding of) God. In all cases, his (exclusive) worship is contrasted in a list of five heavenly idols which were seemingly self-explanatory at the time. The Talmudic passage would seem to have used the same, or very close to that of the Doctrina Addai, although somethings seem to have been lost in transmission:

Mapag (מפג) is not a deity but, as in Syriac, the place

Mabug (ܡܒܘܓ “the spring” or Hieropolis, because it was the cult centre of the Dea Syria; today Manbij);

Tirata (תרעתא) as already mentioned is Atargatis resp. the Dea Syria and not a place(-name)—a well-known site (see above) of her cult was Askelon. The gods mentioned here are חמשה בתי עבודת כוכבים בתי עבודת כוכבים “the five temples of star worship.” that is, celestial bodies: Nabû= Mercury, Bêl=Jupiter, Nikkal= a moon goddess, Taratha=Venus, and Nashara is the name of a star (see P. De Lagarde, Geoponicon in sermonem syriacum, 5:17 1860 ,Versorum quae supersunt, Leipzig, ܥܕܡܐ ܠܕܢܚܗ ܕܢܫܪܐ ܕܐܝܬܘܗܝ ܡܢ ܢܐܘܡܝܢܝܐ ܕܟܢܘܢ ܐܚܪܝ “until the rise of the Naschara, which is the beginning of the month of January;” The seven wandering [planets]…

ܕܐܝܬܝܗܘܢ ܫܡܫܐ ܘܣܗܪܐ ܘܟܐܽܘܢ ܘܒܝܠ ܘܢܪܝܓ ܘܒܠܬܝ ܘܵܢܒܘ

…are Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Moon, Venus and Mercury”—C. Kayser, The Book of Truth, or, The Cause of All Causes, Leipzig, 1889, 55:5).

The mention of Arabia, in connexion with Nashara, cannot be taken as confirmatory evidence in support of the assertion made by Islamic tradition that Nashara had been a deity in and around Mecca. Perhaps this was so—but we simply do not know. The Arabs who venerate “a bird” as god can here only be the Arabs of Mesopotamia—the Talmud as well as the Doctrina Addai do not concern themselves with the Hijaz

This area, roughly identical to the so-called Ǧazīrat al-‛Arab, comprises the lowlands of the Chabur, Euphrates and Tigris in northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and northwestern Iraq. It was also referred to as “Arabia” in ancient times. Here we find e.g., a Ἀραβάρχης (“Arab-archēs—Arab princes”) in Dura-Europos (cf. C. B. Welles et al., The Excavations at Dura-Europos. Final Report V, Part I [New Haven, 1959], 115 No. 20, 5); in Sumatar Harabesi, present-day Turkey, five inscriptions are documented which were found at the old cemetery and bear the Syrian equivalent of this term:- šulṭānā d-ʿarab “Governor of Arab(ia)” (cf. H. J. W. Drijvers & J. F. Healey, The Old Syriac Inscriptions of Edessa and Osrhoene [Leyden, 1999], p. 104f. et passim); in Hatra, a mlk’ dy ʿrb(y) “King of Arabia” is documented (see B. Aggoula, Inventaire des inscriptions hatréenes [Paris, 1991], 92 No. 193, 2; 135f. See also Pliny’s Natural History, V.xxi.86: “Arabia supra dicta habet oppida Edessam, quæ quondam Antiochia dicebatur, Callirhœm, a fonte nominatam, Carrhas, Crassi clade nobile. Iungitur præfectura Mesopotamiæ, ab Assyriis originem trahens, in qua Anthemusia et Nicephorium oppida. … 87] ita fertur [scil. Euphrates] usque Suram locum, in quo conversus ad orientem relinquit Syriæ Palmyrenas solitudines, quæ usque ad Petram urbem et regionem Arabiæ Felicis appellatæ pertinent. This is also the “Arabia” that Paul must have visited (Gal 1:17). It is noteworthy that Fredegar (Chronicon lxvi) locates the Hagarenes even more to the north: “Agareni, qui et Sarraceni, sicut Orosii [Boh. Eorosii] liber testatur, gens circumcisa a latere montis Caucasi, super mare Caspium, terram….” This location can explain the Mandaean and Iranian evidence (see above) of Nashara.

This area, in the north of Mesopotamia, is where historical-critical research locates the crucible of Islam. It is here that the linguistic (the forerunners of Quranic Arabic as well as the heavy Syro-Aramaic impact on the Quranic theological vocabulary) as well as other theological and cultural threads come together, where the Christians in the Sassanid Empire, after the conquest of Heraclius, were suddenly confronted with Christological formulations (Chalcedon) foreign to them, after over two and a half centuries of separation, since the death of Julian Apostata. Here, the only unambiguously identifiable deity of Sura 71,23, scil. Nasr, seems to be certainly at home. Locating his cult to the South, in Arabia deserta, in the empty Hijaz—whose historical and cultural vacantness would only later become the ideal(ised) theological projection surface—has no historical support—and in addition, one would not only have to invent Christianity in the Hijaz, but also Manichaeism!

Sura 71/Sūrat Nūḥ deals with tergiversation, abandoning God/Allah: Noah has warned his contemporaries at God’s behest—”My Lord, I have called my people by night and day (to faith). But my call only caused them to run away more and more: and whenever I called them that Thou mightest forgive them, they put their fingers in their ears, and wrapped themselves in their garments, and persisted (in their state), and became overly arrogant. Then I called on them in public. Then I preached to them in public, and I spoke to them in secret, and I said: ‘Seek forgiveness from your Lord: for He is Oft-Forgiving: He will send down rain for you in abundance; and He will strengthen you with good things and with children, and He will give you gardens, and He will make rivers flow for you…’” (71,4-12). Furthermore, in verses 14-15 Noah asks, “Have you not seen how Allah created seven heavens stacked one on top of the other and set the moon as a light in them?”—i.e., the sky with all its contents, including the sun and moon, bear witness to the existence of God; they themselves are not gods. But Noah finds no hearing; the people remain on their chosen path and say, “do not leave your gods; do not leave Wadd, nor Suwāʿ, nor Jaġūṯ, Jaʿūq and Nasr.”

Contextually speaking, this interpretation of the latter passage fits in the theme of the Sura as a whole, and is quite similar to the admonition found inter alia in in the Doctrina Addai. Taken in this light, we have here a not unfamiliar pious topos, which here the Koranic authors put in Noah’s mouth because it was apparently felt to be somehow appropriate. The theonyms, however, as is also the case in the Talmudic example, where they were conflated with toponyms, have become garbled, yet a further indication that polytheism had long since ceased being an historical reality.

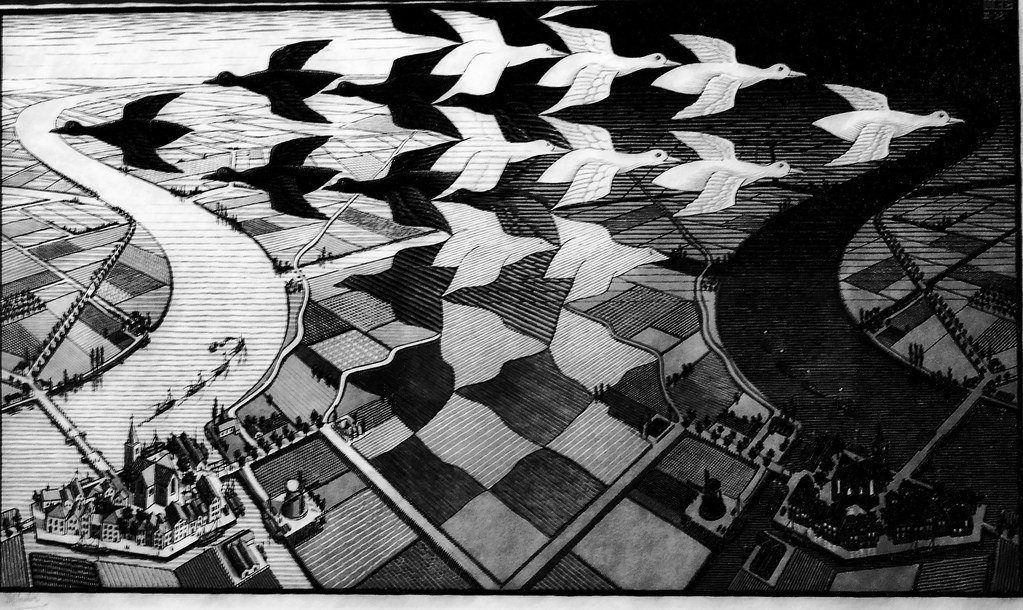

It is in this understanding, however, that this Quranic verse becomes understandable, seeing that, as was just noted, the creation of the heavens, moon, sun etc.—i.e., they are not to be understood as gods, is mentioned just several verses previously. The inexplicable gods mentioned in verse 23 may be just local epithets of the (divinised) celestial bodies, Nsr, the “eagle,” at the same time an astronym, would seem to favour such a proposal. In a Minaean dedicatory inscription (RÉS 2999 from Barāqish in the southern Jawf), the builders self-identify themselves as ʾdm Wdm S2hrn “servants (cf. Arabic ʾādam) of Wdd, the moon.” In this light, it is clear that Wdd could be understood as a(n epithet of) lunar deity. Perhaps then one might be partial to interpreting Suwāʿ as an Arabic realisation of Aramaic shrʾ “moon?” Jaġūṯ, as already been mentioned, is etymologically transparent, “the helper,” a term that might be appropriate for the moon (as attribute) or possibly the sun god?

Be that as it may, however one may choose to etymologise the five “Gods of Noah” in the Qur’an, they are most certainly designations for the (divinised) Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Jupiter and Saturn. As we have sown in the preceding the Classical planets, designated variously, were a common theme in Jewish and Christian polemics against the true faith in the one God. The Qur’anic renditions, as the Talmudic, have been somewhat garbled by later copyists. It is clear that we are dealing here with a topos known in the Syro-Mesopotamian region of Late Antiquity. This is by no means antediluvian and also has nothing to do with the Hijaz, nor originally even with Islam.

Professor Dr. Robert M. Kerr studied Classics and Semitics largely in Vancouver, Tübingen and Leyden. He is currently director of the Inârah Institute, for research on Early Islamic History and the Qur’an in Saarbrücken (Germany).

Featured image: The Almaqah Panel, which bears a Sabaean inscription, mentioning the god Wadd. Likely Ma’rib, Yemen, ca. 700 BC.