Whether your only experience with birds is that of chasing away pigeons stubbornly trying to nest on your balcony, or whether you spent your last pre-Covid vacation trudging through tropical forest in search of the elusive Pinto’s Spinetail, Richard Pope’s Flight from Grace: A Cultural History of Humans and Birds (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021) is a must read. Passionately engaged, wide-ranging, eye-opening, witty, and sometimes laugh-out-loud funny, the book asks the readers to consider the relationship of humans and birds throughout the millennia, ultimately posing a sobering question: is humanity willing to do anything to stop the extinction of birds that is occurring at a shocking and ever-accelerating rate.

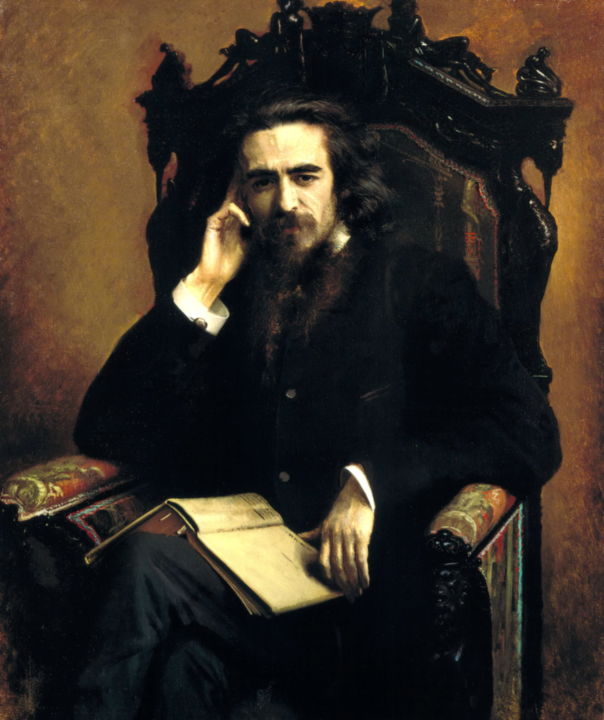

Pope, a distinguished scholar of Russian literature and culture, poet, writer, and a dedicated bird-watcher, brings a scholarly rigour but also a delightful sense of humour and a decidedly fresh perspective to an examination of how humanity thought of birds from the time that humans could think.

His account of the fraught human-bird relationship begins with prehistoric art, images of birds found in caves so deep in the earth that getting there is a terrifying and hazardous journey even today. It is in these caves, or as Pope memorably describes them, these “vast, hidden power sites deep underground in the forbidden realm of powerful spirits…ideal spots for vision quests, rituals, and magic…[like] geodes—plain and unprepossessing on the outside but repositories of stunning beauty inside” (13). that we find images of birds.

Most of these bird images—some painted and some scratched into the cave surface—yield little information to a non-birder. Pope, on the other hand, encountering a 30,000-year-old etching of what is, to the non-initiated, a vaguely-owlish looking bird on the wall of the French Chauvet Cave, teases out a wealth of insights: the etching is most likely that of the Eurasian eagle-owl, “a top predator of impressive size and fierceness, perhaps the largest owl in the world” that frequently inhabits caves; the parallel markings on the body are actually indicative of a back view, with wings folded and “its full face twisted at 180 degree angle to look straight at us over its back” (18). Owls, in case you didn’t know, are among the very few creatures to be able to rotate their faces fully—“something else that makes owls unique and magical…Owls see all” (18). It is inconceivable, Pope argues, that the Owl of Chauvet was drawn only for aesthetic satisfaction; instead, “The owl, in the most sacrosanct part of the cave, was a bird deity with power and capabilities” (19).

Beginning with the Paleolithic owl deity, Pope takes the reader on a dynamic six-chapter tour through time and space, with chapters dedicated to the sacred birds of Mesopotamia and Egypt; Peru; and those of Greece and the Judeo-Christian world. Altogether, it is an impressive demonstration of how an early worship of bird deities morphed into the bird goddesses of the Neolithic era, and then—as humans became more anthropocentric in their outlook—into anthropomorphic gods whose sacred status was reinforced by an addition of wings or who had bird avatars: from the owl deity to the owl of Athena. Here again, Pope’s avian lens allows him to re-examine and challenge well-established conventions. For example, in Homer’s epics, Athena is described as glaukoopis; for those of us who need to brush up on our Classical Greek, Pope helpfully explains that glaukos, when applied to eyes, usually means green or blue, which is how her eyes are rendered in most translations. But another meaning of glaukos (gleaming) is connected to glauks (owl), because that is how the owl’s huge eyes appear to the observer. In Athena’s case, Pope posits, the word really means “owl-eyed, in reference to her knowing glare and that of the bird she once was” (119).

Owls were not the only birds to be deified. Vultures (associated with the cult of the dead), ibises, eagles, doves, and a host of other birds were worshipped for one reason or another, and their images, statues, figurines, and objects associated with them were documented at countless archeological sites all over the world. But why this worship of birds? What is it that makes birds so special and exciting to humans? Pope points to two main factors: flight and song, and devotes two thoroughly documented and lavishly-illustrated chapters to each of these in the second part of his book.

Flight is almost solely associated with birds and, Pope contends, is one of the main reasons for seeing birds as sacred: “flight is miraculous and godlike…and wings are its agent and symbol,” which is why severed avian wings abound in Paleolithic sites (136). From winged ancient goddesses like Ishtar, to winged Greek gods and winged magical creatures, such as Pegasus, wings have always been perceived as the sign of divinity. Drawing on his expertise of working with medieval texts, Pope shows how wings were assigned to angels in Christian iconography from fourth-century onward as a way of visually identifying them as divine (halos were already taken for saints). Pope quotes John Chrystostom, a fourth-century Christian theologian, who explains that angels are shown flying “not because angels have wings…[but to show] the loftiness of their nature. The wings, then, reveal the lofty natures of the powers above” (142). Humans, as ancient myths suggest, and Renaissance-era sketches confirm, have always longed to replicate bird flight, a mark of divinity, and failed to achieve it until recent times, although as Pope points out, flight by plane “is a mere surrogate for real, unassisted flight, and is entirely lacking in magic” (136).

Besides envying the birds their flight, humans have been enthralled by their song. Because of the association of birds with the divine, it was assumed since ancient times that bird song carried arcane knowledge (hence, Roman augurs who specialized in interpreting the will of the gods through birdsong). It is birdsong, Pope contends, that “tightly links humans and birds to each other and both of them to the divine” (164). According to neurobiologists, he writes, humans are closer to songbirds than to their closest relative, the great apes, when it comes to speech acquisition; humans and birds also share a surprising number of neurological similarities. Over and above that, humans and birds share the sheer joy of making music (it turns out that avian brains flood with pleasurable dopamine when they sing), something that poets knew all along, Pope shows, by citing lines about birdsong from the poems of Shelley, Frost, Keats, and other poets.

Indeed, one the many delights of the book is Pope’s readiness to support and further his claims not only by mining various archeological, anthropological, zoological, neurobiological, ecological, and historical sources, but also by finding illustrations in sources as diverse as the Qur’an, Dante, Schopenhauer, Mozart, Lucretius, the Venerable Bede, Marx, J.K. Rowling, and—taking advantage of his superb knowledge of Russian literature and culture—Leo Tolstoy, Nikolai Gogol, Mikhail Bulgakov, Dostoevsky, Russian icons, Russian medieval tales, and so forth. There is also a plethora of photographs of various bird-related artifacts, some of them little known and stunningly beautiful, and of birds themselves, as well as paintings by El Greco, Chagall, and others. The book itself, in fact, is an object of beauty, with the jacket, by the award-winning jacket designer David Drummond, showing a detail from a Georgian-era portrait, where a bright yellow bird perches trustingly on a shoulder of a young woman, and with the light-blue front and sunny-yellow back flaps evoking bird plumage, but also the skies and the sunshine of the birds’ higher element. Pope would have undoubtedly pointed out here (as he does in the book) that we share our sense of aesthetics with the birds.

All this beauty makes the ugly picture that Pope unfolds for us in the ultimate section of the book, titled “Our Betrayal of Birds,” even more shocking. Pope’s central thesis is that as humans moved toward anthropocentrism from the Neolithic era onward, and developed modes of thinking which encouraged homo sapiens to see himself as separate from and towering above all the other species on the planet, our attitude toward all other creatures who share the planet with us became shamelessly predatory. Focussing on the Western Civilization, Pope argues that Judaism and Christianity, in particular, promoted a worldview in which man was created in an image of a non-animistic god, and completely separated from his fellow creatures, and that the rise of science during the Age of Reason drove “the last nail into the coffin of animistic thought” (219) with dire consequences for our fellow creatures.

Taking among his examples the lines from Genesis 9:2-3, about God telling Noah that all beasts, fowl, fishes, and other creatures are delivered into his hand, Pope makes the case that Judaism and Christianity convinced followers that all non-human life forms are to be used as humans see fit. One could, of course, counter this argument by pointing, for example, to the prohibition in Deuteronomy against plowing with a donkey and an ox tethered together, as God’s directive that mankind should take care of animals and their needs. Nonetheless, the evidence that Pope marshals of the appalling ways humans have actually been treating their fellow beings, namely birds, over the last two millennia is both disturbing and undeniable. That birds should be treated this way, creatures whom we have once worshipped and who still obsess us (Pope writes that almost 1 in 4 North Americans is a bird enthusiast), is particularly outrageous.

We have killed birds for their meat, their feathers (as part of our fashion industry and our cultural practices—ceremonial headdresses made out of eagle plumes, birds of paradise feathers, and the like), their habitats (forests cleared for farmland and golf courses), the damage they do to crops (forgetting that they also kill insects that wipe out our crops), for science (no matter how inane the experiment and how obscure its purpose), for exercise (hunting), for fun (that’s how the great auk became extinct), on purpose and inadvertently (the bird population of the island of Guan was wiped out after the unintentional introduction of the brown tree snake). Pope pulls no punches: we are all culpable, from industries and large corporations, to small-time farmers, to denizens of tall buildings (bright lights confuse and kill migrating birds), to backyard gardeners (depriving birds of food by dousing our plantings with herbicides and insecticides), to cat owners (free-roaming cats kill “between 1.3 billion and 4 billion” birds a year [202]). We, humans, homo sapiens, the species, are responsible for the decline of bird populations throughout the world and for the extinction of 190 species of birds in the last 500 years alone (currently, 1,200 species are under threat of extinction). No wonder Pope chose as an epigraph for his concluding chapter the words of the embittered prophet Jeremiah: “Destruction upon destruction is cried…all the birds of the heavens were fled.”

But Pope’s book is not a dirge—it is a call to action. Any student of Russian literature will recognize the title of his last chapter, “What is to be Done?” as the title of the 1863 radical novel written by Nikolai Chernyshevsky with a prescription of how to take Russia to a radiant future—a novel frequently called a revolutionary’s handbook. Pope is also advocating for a revolution—a revolution in how we think about birds and nature itself. We, humans, are not that different from birds, nor are we separate from nature, and the decisions that we make in our everyday life must take into consideration our larger home and all of our fellow residents, feathered and not. Ultimately, we must become “better stewards of the earth” (240).

Unlike the utopist Chernyshevsky, however, Pope cannot be accused of naivety: “Because of our propensity for violence, our greed, and our selfishness,” he writes, “it is unlikely that we humans will act collectively and soon to halt the degradation of our biosphere…Most people simply do not care and are quite unwilling to make any sacrifice for nature if it entails any degree of discomfort for themselves” (245). All the same, Pope points out, if we are too corrupt as a society to act collectively, we can still act individually—in fact, we must, even in the face of failure: “Make no mistake about it,” he writes, “the issue is one of morality.” To that end, Pope provides a 13-point practical list of what each one of us can do to “slow down and even prevent some of this degradation [of the biosphere], helping birds and other animals to survive and giving our own lives more meaning through ethical conduct and a closeness to our environment” (239).

Essentially, Pope proposes that each one of us becomes a dissident within our criminally indifferent society, no matter how hopeless it might seem. Citing Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s position on the “ontological existence of evil and its unstoppable nature,” Pope comes to the same conclusion: “We may not be able to stop [the desecration of nature], but we can refuse to abet it” (233). Is it a foolish act when seen in the context of the seemingly inexorable degeneration of our biosphere and our individual helplessness? Perhaps. But Pope leaves us with this thought: “True folly is to assume that we will not damage ourselves severely if we sit back and just watch as others recklessly damage the planet” (248). A world without birds is a horrible prospect. Let’s hope it never comes to pass.

Maria Bloshteyn, PhD, researches Russia and the West and is the author of The Making of a Counter-Culture Icon: Henry Miller’s Dostoevsky. She is also a literary translator and has published Alexander Galich’s Dress Rehearsal: A Story in Four Acts and Five Chapters, and Anton Chekhov’s The Prank. Her various translations have appeared in a number of journals and anthologies, including The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry. Her most recent book is Russia Is Burning. Poems of the Great Patriotic War.

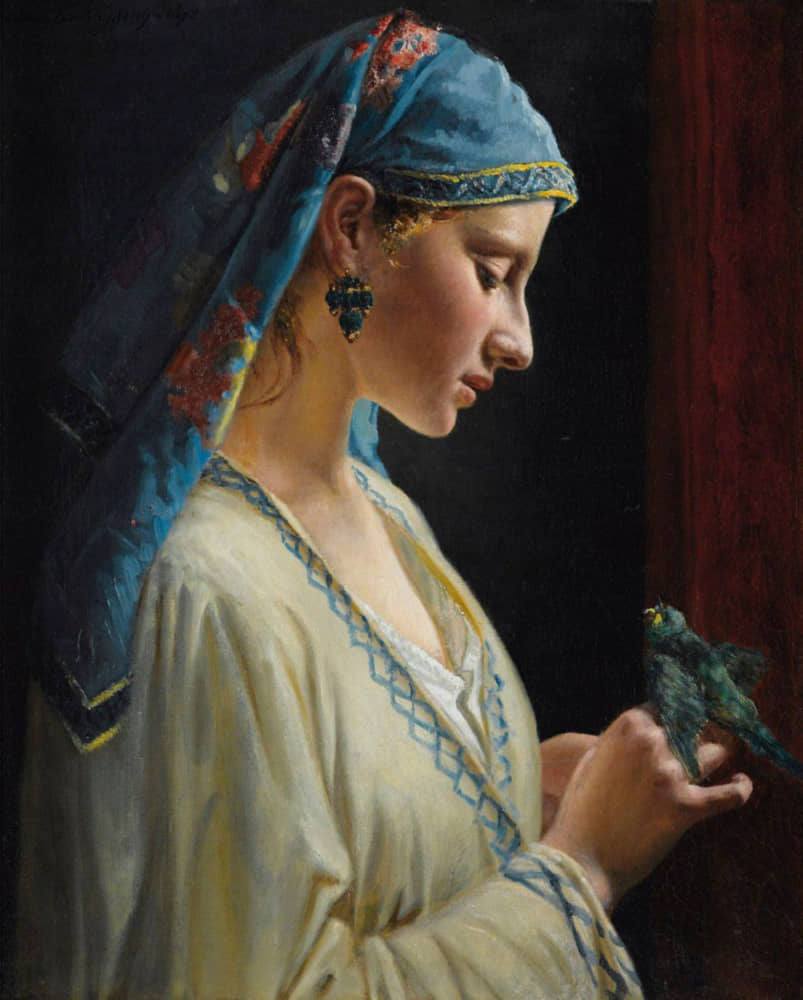

The featured image shows, “Young woman with parrot,” by Frédéric-Pierre Tschaggeny, painted in 1872.