This month, we are so very delighted to present this unique interview with Nikita Krivoshein who was born in Paris, in 1934. His family of Russian noblemen, fled communism during the First Wave of emigrants. His grandfather, Alexander Vasilievich Krivoshein, was Minister of Agriculture in the Russian Empire and Prime Minister of the Government of Southern Russia, under General Wrangel. His father and uncle were decorated fighters in the French Resistance during World War II. His father was arrested by the Nazis and sent to Buchenwald and then Dachau.

Nikita, along with his father and mother, returned to the Soviet Union, in 1948, thinking that they were going back home to peace and security. Instead, his father was soon arrested and sent into the Gulag.

Nikita himself was arrested in August 1957 by the KGB for an unsigned article in Le Monde about the Soviet invasion of Hungary. He was convicted and sent into Mordovian political camps (the Gulag), where he worked at a sawmill, as a loader. After his release from prison, he worked as a translator and simultaneous interpreter, from 1960 to 1970. He was able to return to France in 1971. His parents also returned to France in 1974. He lives in Paris. He has just published a book about his Gulag experiences.

Nikita Krivoshein is interviewed by Christophe Geffroy of La Nef.

Christophe Geffroy (CG): You have had an unimaginable journey. Birth in France, then departure for the USSR where you came to experience the gulag and return to France. Could you summarize it for us?

Nikita Krivochein (NK): Heaven was merciful and generous. I was able to return to France, to reintegrate myself, to bring my parents back, to found a home. Among the young emigrants taken to the USSR after the war, those who had this chance can be counted on the fingers of one hand. From Paris, I was able to see the collapse of the communist regime, and this without bloodshed! A great wave of murderous settlements of accounts was more than likely. We survived in the USSR physically as well as in our faith, our vision. But how many “repatriates” preferred to make themselves invisible, to depersonalize themselves to survive. My return to France was, and remains, a great happiness!

CG: Why did your parents return with you to the USSR in 1948, when the totalitarianism of Soviet communism was manifest?

NK: In the immediate post-war period, the totalitarianism was muted and less obvious. From 1943 onwards, Stalin had noticed that the Russians were not very keen on being killed by the Wehrmacht in the “name of communism, the radiant future of all mankind,” so he changed his tune and started to invoke “Great Russia,” its military, its culture, and reopened the churches. He changed the national anthem and renounced the motto, “Proletarians of all countries, unite,” revived the officer corps. In 1946, he returned to the repression of the Church. In 1949, he launched a very dire wave of arrests (including that of my father). But during the war the illusion of a renunciation of communism worked.

CG: What was the most important thing about your life in the USSR and your time in the camps?

NK: I have intimately felt and internalized that Hope is a great virtue. It would have been enough to stop living it, even for a moment, to sink into the great nothingness of “homo sovieticus.”

Our family was one of the few in the Russian diaspora in Paris who did not live in misery. Until the outbreak of the Second World War, my early childhood was happy. With my parents, we lived in a large three-room apartment on the banks of the Seine, opposite the Eiffel Tower. We lived in a comfort that was rare at the time, especially in the families of Russian emigrants. My father had studied at the Sorbonne and had become a specialist in household appliances. When I was born, he was chief engineer at Lemercier Frères. My father owned a black Citroën, and with my mother they traveled a lot. I was an only child, born late.

In June 1946, Stalin organized a vast propaganda campaign – amnesty was proposed to all former white emigrants in France, with the delivery of a Soviet passport and the possibility of returning to their homeland. Pravda came out with a new, flashy slogan: “For our Soviet homeland!” – instead of “Proletarians of all countries, unite!” And the radio no longer played The International but Powerful Russia… The Russians thought that “debolshevization” was indeed launched.

I found myself in the USSR in 1948 and then for many years I was obsessed with the idea of running away. Our ship, which left from Marseille, docked in the port of Odessa. It had on board many Russians who wanted to return to the country. The next day was May 1st. We were waiting. A soldier in a NKVD uniform entered our cabin, asked my mother to open her purse and confiscated three fashion magazines. “This is forbidden!”

We were told – you are going to Lüstdorf, an old German town near Odessa. On the landing pier, trucks were waiting for us, driven by soldiers. We were taken to a real camp, with watchtowers, dogs, barbed wire and barracks! We were transferred to Ulyanovsk in a wagon (40 men, 8 horses, 12 days trip). In 1949 my father was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in the camps for “collaboration with the international bourgeoisie.” My happy childhood was over. I relate all this in my book.

CG: In your book, you warmly evoke the beautiful figure of Canon Stanislas Kiskis, a Lithuanian Catholic priest. What place did religion have in the Gulag and what relationship did it fashion among Orthodox and other Christians?

NK: This question would require a whole study. In 1958, when I arrived at the camp in Mordovia, an old deportee said to me in French: “Allow me to introduce you to Canon Stanislav Kiskis.” That meeting marked my entire stay in deportation. Our friendship continued after our release.

He was a short, stocky man. His face, his head, what a presence! One could immediately sense that he was a strong person in every respect. A week had hardly passed when Kiskis was transferred to our team to load trucks. There were about ten of us, almost all from the countryside, war criminals, quite a few Ukrainians and Belorussians, all of them certainly not ordinary fellows.

Kiskis had chosen the method of Socrates’ maieutics for his mission.

I guess he had practiced his speech in previous camps. On the subject of the “nature of property,” for example, without addressing anyone in particular, Father Stanislav would ask, “And this pile of stones, who owns it? What about the land on which the pile is located?” The answers were obvious. “To no one.” Or, “to those stupid communists and Chekists!” Or, “We don’t know.”

Stanislav and I used to analyze Roman dogmas such as the Immaculate Conception, the rational proof of God’s existence and papal infallibility. We did this exclusively from an analytical and historical point of view. The canon-psychotherapist had to express himself in a more delicate and confused way than when he was dealing with property, but he succeeded in demonstrating what distinguishes work as a punishment inflicted on Adam from that which is the principal sign of our likeness to God. He even succeeded in establishing a quality, a usefulness and a saving side to certain aspects of forced camp labor. On his return to Lithuania, he was warmly welcomed by the Catholic hierarchy.

CG: You knew Solzhenitsyn. What do you remember about the man and, more than twelve years after his death, what can we say today about the historical role he played?

NK: My father was in the First Circle camp at the same time as Solzhenitsyn. It was a lifelong friendship between them. When I left the former USSR, Alexandr Issaevich honored me by coming to say goodbye and encouraging my decision to emigrate.

CG: More generally, what was the influence of the dissidents in the USSR? In what way are they an example for us today?

NK: It is certain that the resistance fighters in the USSR (preferable to “dissidents”), by their actions, hastened the collapse of the system. They are an example because, according to Solzhenitsyn and Sakharov, they did not accept to “live in a lie.” But the Communists continue to hate and vilify them.

CG: When we read in your book, the amount of suffering that you and your parents had to face, haven’t we in the West lost the tragic sense of life?

NK: It is enough to be aware of mortality. One can very well do without the Gulag to be aware of the tragedy of existence.

CG: How do you analyze the current situation in Russia? Has the page of communism definitively been turned?

NK: Alas, no! As long as the “stuffed man,” as we used to call the tenant of the mausoleum, remains in his quarters, nothing is irreversible. Stalin worshippers remain numerous, and monuments to this criminal are even erected clandestinely here and there.

CG: While Nazism was unanimously rejected, the same cannot be said of Communism, whose crimes do not arouse the same repulsion (statues of Lenin can still be found in Russia). Why such a difference? And why should Russia not engage in an “examination of conscience” about Communism?

NK: National Socialism never promised anyone a happy life. Communism, on the other hand, has managed to gain acceptance as the “bright future of all mankind.” When a genuine Nuremberg-style decommunization takes place, I will celebrate it wholeheartedly. But the utopia of the earthly paradise has the gift of not setting free its followers.

CG: You are a believer. How do you see the future of our societies, which are moving further and further away from God? And how do you see the future of relations between Orthodox and Catholics?

NK: Five generations of believers have lived under a deicidal regime. The martyrs cannot be counted. The Christian revival was felt in Russia long before 1991. The period of agnosticism that we went through is coming to an end. Man cannot live on bread alone for too long a time. A new generation, not genetically infected with “homo sovieticus,” has appeared. The parishes are full of young people.

This articles appears through the kind courtesy of La Nef.

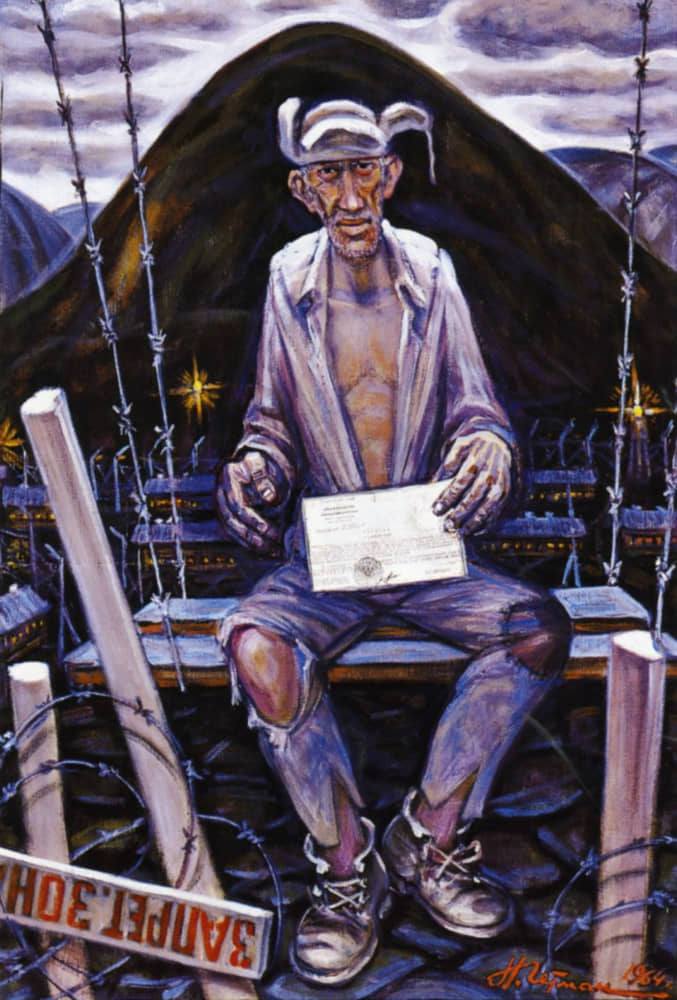

The featured image shows, “Rehabilitated,” by Nikolai Getman, ca. 1980s.