There are two confused and confusing but intertwined debates that I want to address, and to do so by referring to the seemingly unlikely trio of writers, Hegel, Conrad, and Naipaul.

What are those two debates? The first and slightly older international debate is about the relation between colonial powers and their now former colonies. The second largely domestic debate is about the relation of “white” people to people of “color.”

I would suggest at the very beginning that they are the same debate, and that the debate really centers on whether a particular set of cultural norms originating among Western Europeans and their major heirs (including North Americans, Australians, etc.) is superior to other non-Western norms.

Neither debate is about skin color or race. Prominent and successful members of Western European Cultures have a vast variety of skin colors and physical features, while many of the dysfunctional members of these same cultures are “white” (i.e., have Western European ancestors).

What Hegel, Conrad, and Naipaul provide is an ongoing account of why Western cultural norms have emerged as superior, and in what sense they are superior.

As a preliminary example, I note that in response to the recent covid pandemic the viable vaccinations were developed in the U.S. and the U.K, not in China, not in India, not in Russia. In addition, there was an immediate Western concern for redistribution to the rest of the world.

Individual Freedom

The preeminent norm of Western culture is individual freedom or autonomy. By “individual freedom” I mean that each and every individual chooses how he/she wants to live. Each of us is not assigned a role in advance, rather each of us decides, for example, what career we want to pursue, where we want to live, and to whom we wish if we so desire to be married. This is in the first instance a pursuit not a guaranteed outcome. Second since this is a privilege or set of privileges extended to all, no one individual can demand that others fulfill that one individual’s pursuit.

This has been best expressed by Oakeshott:

Almost all modern writing about moral conduct begins with the hypothesis of an individual human being choosing and pursuing his own directions of activity. What appeared to require explanation was not the existence of such individuals, but how they could come to have duties to others of their kind and what was the nature of those duties… This is unmistakable in Hobbes, the first moralist of the modern world to take candid account of the current experience of individuality. He understood a man as an organism governed by an impulse to avoid destruction and to maintain itself in its own characteristic and chosen pursuits. Each individual has a natural right to independent existence… And a similar view of things appeared, of course, in the writings of Spinoza… this autonomous individual remained as the starting point of ethical reflection. Every moralist in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is concerned with the psychological structure of this assumed “individual”… And nowhere is this seen more clearly to be the case than in the writings of Kant. Every human being…is recognized by Kant to be a Person, an end in himself, absolute and autonomous… as a rational human being he will recognize in his conduct the universal conditions of autonomous personality; and the chief of these conditions is to use his humanity, as well in himself and others, as end and never as a means [only—italics added]… no man has a right or a duty to promote the moral perfection of another… we cannot promote their “good” without destroying their “freedom” which is the condition of moral goodness (“The Masses in Representative Democracy”).

In another context, I have argued that the political and economic success of Western Culture depends on economic, political, and legal institutions that are premised on the centrality of individual freedom (namely the technological project or the control of nature for human benefit [Bacon], free market economy [Adam Smith], limited government [Locke, Madison], the rule of law [Coke, Dicey, Hayek], and a culture of personal autonomy). It has a historically-grounded but contingent connection with the English language, reflecting the fact that the earliest working out of the full panoply occurred first in England and then spread in varying degrees from there. It is no accident that both Conrad and Naipaul consciously adopted Anglo culture and achieved creative excellence by writing in English.

Throughout most of history and everywhere in the world, human beings have identified themselves as members of a community. There were neither autonomous individuals nor anti-individuals. The most important event in modern European history is the rise of the autonomous individual first appearing in Renaissance Italy (13th-15th centuries). There are no autonomous individuals anywhere before the Italian Renaissance. Autonomous individuality is a feature of Western European civilization and later spread elsewhere. All creative activity [creative/destruction] is the product of autonomous individuals: “It modified political manners and institutions, it settled upon art, upon religion, upon industry and trade and upon every kind of human relationship.”

The mind-set of the Autonomous Individual, auto-nomous (self-rule is the translation) reflects the imposition of order on themselves; self-disciplining, not self-indulgence or requiring outside control and direction; risk-takers, self-defining; self-respect (something you give to yourself; not the self-esteem that comes from others), pursuing self-chosen courses of action rather than playing traditional roles.

Not everyone makes the transition – some are left behind (by circumstance and by temperament) namely anti-individuals.

The emergence of this disposition to be an individual is the pre-eminent event in modern European history….there were some people, by circumstance or by temperament, less ready than others to respond…the counterpart of the…entrepreneur of the sixteenth century was the displaced laborer….the familiar anonymity of communal life was replaced by a personal identity which was burdensome….it bred envy, jealousy and resentment….a new morality….not of “liberty” and “self-determination,” but of “equality” and “solidarity”….not…the “love of others” or “charity” or… “benevolence”… but… the love of “the community” [common good]….[the anti-individual or mass man] remains an unmistakably derivative character…helpless, parasitic and able to survive only in opposition to individuality….[only] The desire of the “masses” to enjoy the products of individuality has modified their destructive urge.

It was once fashionable to claim that Western economic success was a product of the colonial exploitation of natural resources. We now know that is not true, and the truth has been magnified by the inability of resource rich non-Western countries to be successful on their own. There are also some interesting half-way houses: e.g., China finally understood about technology and markets even though it still does not get the rest of the story.

The process of reacculturation—recognizing the need to leave the old communal framework behind—is a challenging and a painful one. There is the feeling (temporary) of being inferior or inadequate (like learning a new language from an accomplished speaker); of sometimes feeling patronized; of being prejudged (skin color, accent, posture, dress, etc.) as an outsider by those ignorant of your transformation. Success in making the transition is not a matter of intelligence. Frustrated, put off by the process, or the fear of failure creates a class of novices who ultimately fail, psychologically, to complete the journey. Some of these become celebrity critics of Western culture, famous for the books they write in a Western language detailing the “shortcomings” (challenges) of a culture of individualism. They soon ally themselves with homegrown critics, and it is ironic how many of the critics of Western Culture do not hesitate to accept being subsidized by universities in the culture they claim to despise—“to enjoy the products of individuality has modified their destructive urge.”

True to form, they never produce a positive account of a viable alternative—after all doing such runs the risk of critical retaliation—fear of failure again. We do not always live up to our stated norms, but that alone does not deny the existence of those norms (except in the minds of social scientists who do not understand what a norm is).

An example of the failure to understand the norms is the claim that autonomous individuality is not a universal truth that exists independent of any specific historical context. Metaphysical universality is indeed a norm/truth within the Western mind. However, membership in the community of autonomous individuals is a universal invitation, and it is in the recognition of such that Naipaul will add his contribution.

Alas, even in Western cultures there are people who neither understand nor cherish these norms. Accepting responsibility for one’s own life pursuit is neither obvious nor easy. Many people simply want others to be responsible for them. This is clearly something that many parents and teachers worry about with regard to their children or other young people. In response, there are numerous political, social, educational, aesthetic, and intellectual movements designed to cater to those who do not want individual freedom and responsibility

Of special importance, however, are the number of people not born into a Western Culture who migrate to the West in search of individual freedom. I am pleased to meet them all the time. To be sure, many of those engaged in these now massive migrations merely come in search of greater economic and legal benefits without any understanding of why those benefits only exist in some places – perhaps they think it’s an accident or the result of magic, or more likely they do not, initially, think at all. In any case, the migrations are all in the same direction: north and west.

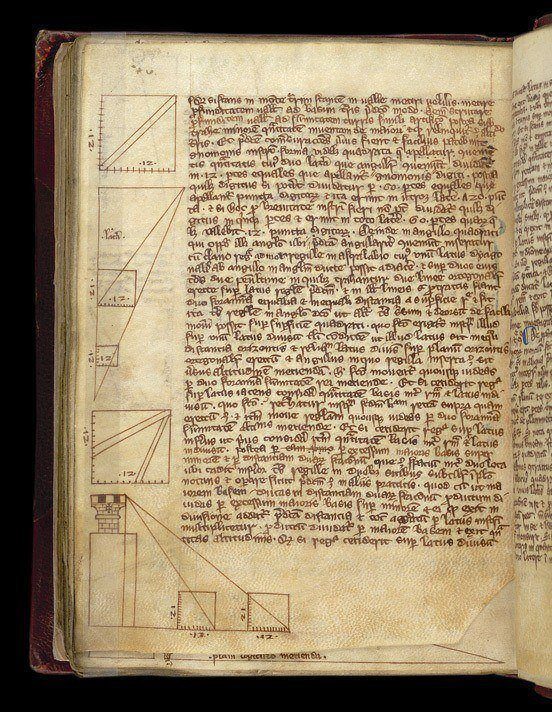

Hegel

In the Philosophy of Right, Hegel initiated the idea of history as a development toward the consciousness of freedom. Hegel describes four stages in the formation of the self-consciousness of freedom: Oriental, Greek, Roman, and Germanic. In the “Oriental” stage, freedom is largely unrecognized and communities contains only the rudiments of freedom. The world-view of the Oriental realm arises in patriarchal communities where only one person, technically the king, is free. The classical Greek world is superior to the Oriental world because the Greeks have a greater sense of freedom (communities that are self-governing are free). However, they are not fully self-conscious of their freedom because the satisfaction of needs is carried out exclusively by a class of slaves. The Romans embody the third stage and display a greater sense of individuality, but ethical life is divided between the recognition of an aristocratic private domain in conflict with freedom in a democracy. In both classical Greece and Rome, only a portion of the community is free. With the advent of the ‘Germanic’ world, the idea that everyone can have this freedom emerges. This idea of universal freedom is facilitated through Christianity, which acts as a bridge linking the ancient world of limited freedom to the modern world where everyone can be free.

Two things are worth noticing about freedom in this earlier Hegelian work. First, the meaning of “freedom” is not some timeless abstraction but evolves over time. Cultural norms are not fixed and frozen entities. Second, “freedom” does not start out as a universal norm but involves a dialectical struggle.

For Hegel, freedom and self-consciousness are intricately linked.

The Christian doctrine that man is by nature evil is superior to the other according to which he is good. Interpreted philosophically, this doctrine should be understood as follows. As spirit, man is a free being [Wesen] who is in a position not to let himself be determined by natural drives. When he exists in an immediate and uncivilized [ungebildeten] condition, he is therefore in a situation in which he ought not to be, and from which he must liberate himself. This is the meaning of the doctrine of original sin, without which Christianity would not be the religion of freedom.

For Hegel, then, humans have original sin, and life serves as a realm in which humans struggle to release themselves from this condition of slavery to natural drives. Christianity is the religion of freedom insofar as it involves the redemption of mankind.

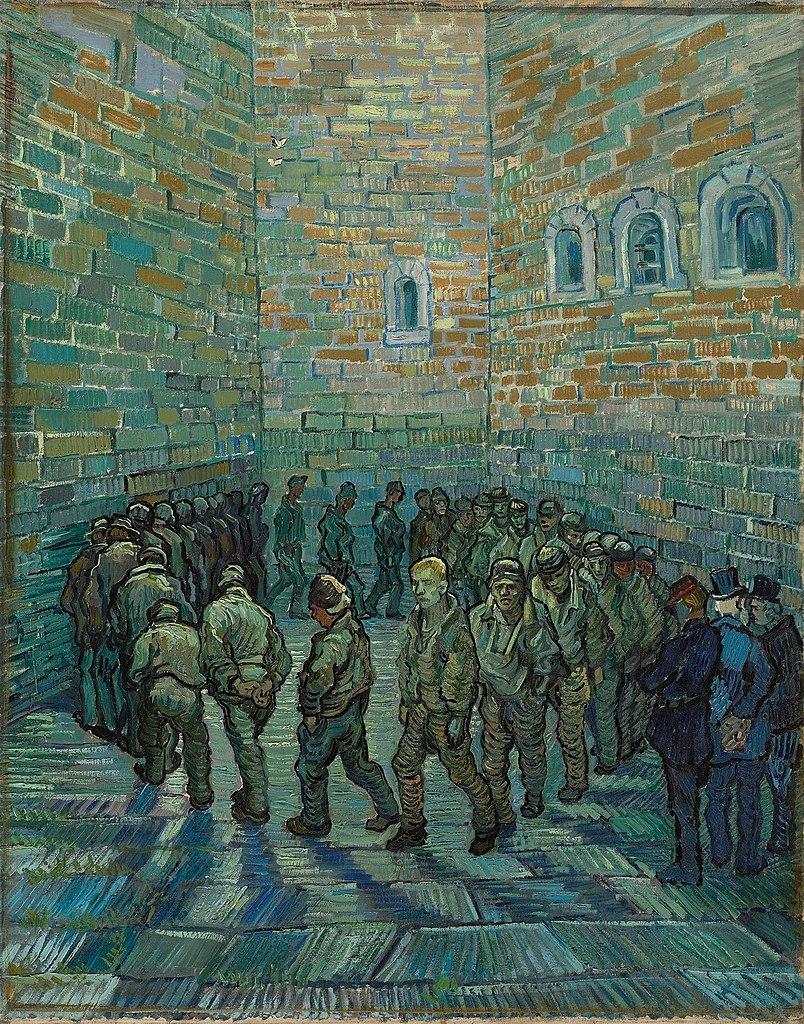

In the Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel explores the dialectical struggle of this relationship between the self-consciousness of freedom in the relation of masters to slaves. For Hegel, the self-consciousness of freedom exists only in being acknowledged. Recognition” is crucial to self-consciousness. Autonomous individuals have a need for recognition by other individuals. More specifically, individuals desire to be acknowledged by other self-conscious individuals. The master-slave (parent-child, teacher-pupil) relationship is problematic because it does not involve the mutual recognition of equals.

Hegel identifies the master as the independent consciousness whose essential nature is to be “for itself.” He identifies the slave as the dependent consciousness whose essential nature is simply to live or to be “for another.” The master achieves recognition but it is unsatisfactory because the slave is not another autonomous individual. Moreover, the master does not engage in the necessary labor that allows individuals to arrive at a sense of their own agency. The conventional perception of the master as free and the slave in bondage soon gets flipped on its head; the truth of the independent consciousness actually belongs to the servile consciousness of the slave. The slave, therefore, might have the better understanding of freedom. Through the process of withdrawing into itself, the consciousness of the slave will be transformed into a truly independent consciousness. The fear of the master is the beginning of the slave’s wisdom, but work completes this process of realization and enables the slave to become conscious of who he truly is. Thus, the master-slave relationship takes on a character that is directly opposite to the degrees of freedom traditionally associated with the master and slave.

For Hegel, then, the respect of inferiors is never sufficient. Individuals who want to achieve satisfactory recognition from others must obtain this acknowledgement from selves who are also self-conscious and free. Therefore, autonomous individuals should have an interest in other people achieving freedom and a sense of self-consciousness. Any autonomous individual will want to see his/her own freedom reflected in other people. In varying ways, Westerners will come to experience the discomfort of being masters.

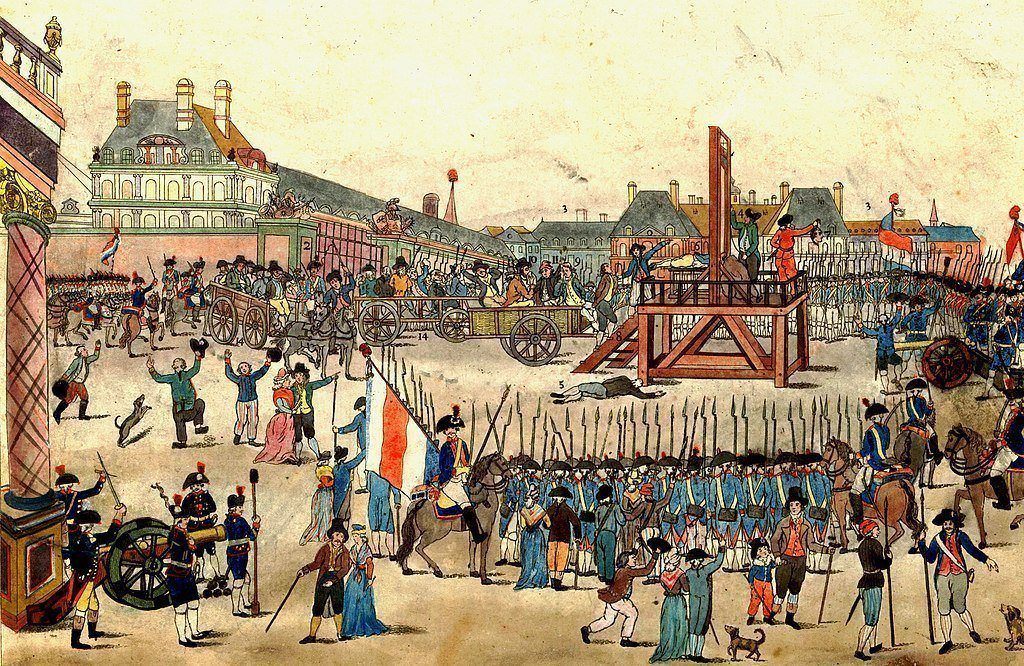

“Promoting” personal autonomy in other individuals is not an easy process. It is a complicated undertaking in which difficulties can arise on the part of the “inferior” as well as on the part of the “superior” when either attempts to equalize the relationship. Colonialism in particular raises these issues of freedom and authority as well as providing a backdrop in which the Hegelian thesis may be tested on the grounds of its accuracy and its practicality.

Both Joseph Conrad and V.S. Naipaul present colonial narratives that serve as exemplifications of Hegel’s conception of freedom. Conrad identifies a problem with colonialism insofar as it reinforces the perception of Europeans as masters and others as slaves. Naipaul builds on Conrad’s argument but adds the recognition that while liberty as the removal of an “outside” constraint can be bestowed on others “inner” freedom cannot be given to others but is something they must work out for themselves.

Joseph Conrad

Conrad’s Heart of Darkness raises three important questions: In what ways does Conrad view Western civilization as more morally advanced? How does colonialism corrupt both western and non-western cultures? In what sense are Europeans enslaved by colonialism? In his works, Conrad displays an anti-colonial sentiment and suggests, like Hegel, that the admiration of an inferior is never satisfactory. He views colonialism as destructive insofar as it casts Europeans as masters and others as slaves. For Conrad, like Hegel, this master-slave relationship is ultimately and inherently undesirable.

Conrad, however, does not center this need for recognition on reflective freedom. His European characters are often engaged in imperialistic projects, and they do not seem particularly concerned with granting freedom to non-Europeans, or even with promoting autonomy in each other. Freedom is a definite concern for Conrad, but he does not insist that humans have a responsibility to help others achieve freedom. Conrad criticizes colonialism for its cruelty, demoralizing effects, and its inhumanity, but he does not go beyond this critical step, as does Naipaul, to propose a project of exporting freedom to others. For Conrad, the Western man is more morally advanced than savages because he has a conception of original sin and thus recognizes his own limitations; the savage exists in a prior state of consciousness/darkness.

Conrad, too, emphasizes the connection between individuals and history. Frederick R. Karl, his biographer, has described Conrad as “a Hegelian without the character of an Idea or an Ideal.” Conrad views mankind as caught in a web of moral and political turmoil in which humans are constantly struggling to overcome the powers of darkness. He does not see any final resolution of the human predicament.

Like Hegel, Conrad views the present world as divided into various stages of historical development. The narrator relates how the Thames has serviced “all the men of whom the nation is proud, from Sir Francis Drake to Sir John Franklin.” Marlow adds the story is actually an historical account of conquest. His “seaman’s yarn” begins with a reflection on England’s historical origins. “I was thinking of old times, when the Romans first came here, nineteen hundred years ago.” Marlow speculates on the experiences of a commander of a “trireme in the Mediterranean, ordered suddenly to the north” and how he might have encountered “the utter savagery” of uncivilized England. These reflections are a preface to the story of European imperialism. First England is conquered, and then it conquers other lands.

History for Marlow is a history of conquest, but issues of freedom arise because conquest involves a restructuring of previously established norms of social organization, political institutions, belief systems, and even natural environments. He takes particular interest in the mode of conquest of imperialism, and he expresses clear concerns about the moral implications of this practice. He carefully distinguishes between those who conquered England and the current English imperialists: “Mind, none of us would feel exactly like this [the Roman commander and his crew],” Marlow tells his fellow passengers. “What saves us is efficiency—the devotion to efficiency… these chaps were not much account, really. They were no colonists… They were conquerors, and for that you want only brute force—nothing to boast of, when you have it, since your strength is just an accident arising from the weakness of others… The conquest of the earth which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion… [it] is not a pretty thing when you look into it much. What redeems it is the idea” of its more efficient use. This is “not a sentimental pretense but an idea; and an unselfish belief in the idea—something you can set up, and bow down before, and offer a sacrifice to….” The conquest of nature, what we have called the “Technological Project” becomes a replacement for religion.

The “conquest” is only redeemable as the idea that colonizers are “bearers of a spark from the sacred fire” of civilization. But this is an illusion. In Heart of Darkness, the European colonizers do not bring civility to the savages. In fact, just the reverse occurs. The wilderness makes barbarians of the Europeans. The great colonial project is turned upon its head; it operates on the false and fatal assumption that the wilderness and its savage inhabitants will be the only ones conquered. The conquest of both land and its human inhabitants is a cruel and ugly process. Marlow’s description of the African natives, is that “[t]hey were dying slowly… They were not enemies, they were not criminals, they were nothing earthly now—nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation.”

Kurtz, the chief of the Inner Station, comprises “[a]ll Europe.” “Each station should be like a beacon on the road towards better things, a center for trade of course, but also for humanizing, improving, instructing.” This dual purpose, Conrad suggests, is in itself a contradiction. Kurtz professes to bring civilization and virtue to the natives, but the ivory trade will mean their exploitation. Kurtz engages in the impossible task of humanizing the natives by taking away their humanity.

For Hegel, the crucifixion represents not only a reconciliation of opposites but also the descent of heaven to earth; the ideal meets the material world in the figure of Christ. There is, then, a notion of redemption in Hegel, and this notion of redemption is intimately connected with the idea of freedom. Christianity itself acts as an intercessor between the ancient and the modern worlds through Christ and promotes this liberation from original sin. In Conrad, attempts to achieve redemption never meet full success. You might treat the natives better but you cannot bring them true freedom. Thus, Conrad shares with Hegel the realization of humankind’s essential wickedness, but he does not share Hegel’s notion of redemption or Hegel’s optimism about the future.

Hegel recognized labor as one of the means by which individuals arrive at self-consciousness. In Heart of Darkness, Marlow makes the same observation: “I don’t like work—no man does—but I like what is in the work—the chance to find yourself. Your own reality—for yourself, not for others—what no other man can ever know.” Thus Conrad, like Hegel, suggests that labor gives individuals a sense of their own agency.

Europeans are more morally advanced than the colonial savages they rule insofar as they have a conception of original sin so understood. Even though the civilized world may not uphold the morals it espouses, and even though the Western world may not subscribe to all of the right ideals, it nevertheless has a recognition of those morals. The savage does not have this awareness. When Marlow journeys deeper and deeper into the jungle, he relates, “Going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginning of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings…. [Y]ou lost your way on that river as you would in a desert, and butted all day against the shoals, trying to find the channel, till you thought yourself bewitched and cut off for ever from everything you had known once—somewhere—in another existence perhaps.” In this sense, history, for Conrad as for Hegel, also traces a development of human self-consciousness. Conrad views the savages as living in another stage of history, one that is located “in the night of first ages.”

V.S. Naipal

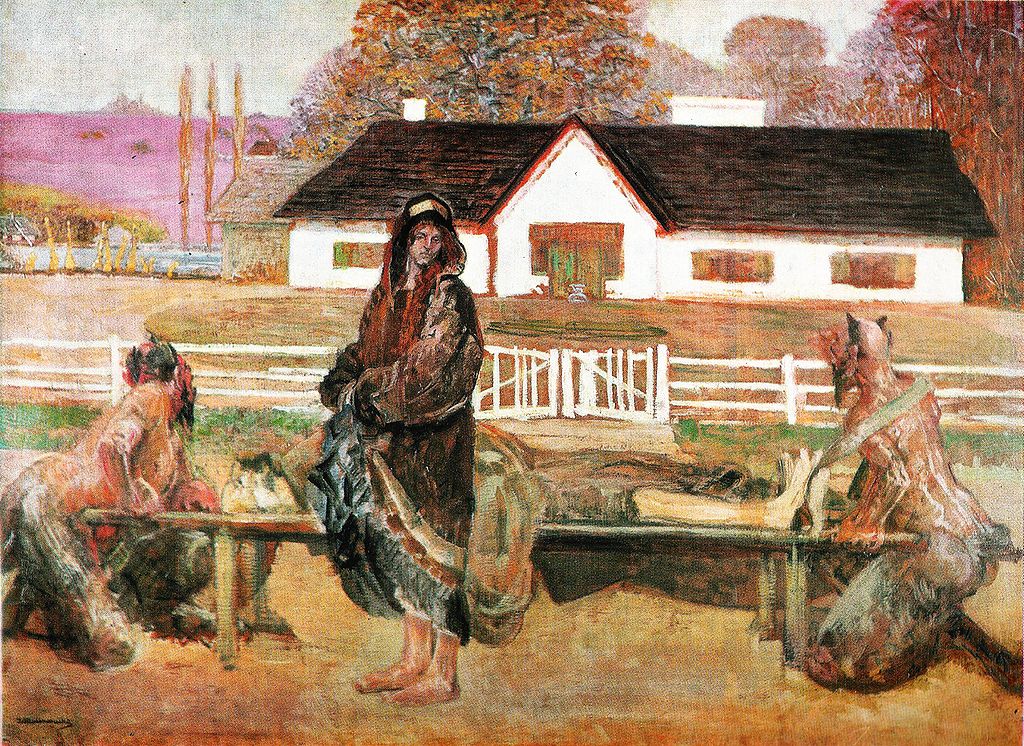

Naipaul’s work is usefully compared and contrasted with that of his favorite English author, Conrad. Like Conrad, Naipaul comes to his place at the very center of English culture as an outsider. Born in Trinidad into a Hindu family, he was part of the Indian community that had migrated a century ago to work the West Indian cane fields as indentured laborers. From early on, he felt the as yet inarticulate sense of marginality that fills his books, the irrelevance of such places and their inhabitants to the mainstream where significant deeds are done. Like Conrad’s restless wanderings as a sea captain, Naipaul for thirty years has recrossed the globe as expressed in his travel essays. Naipaul is Conrad’s spiritual heir, writing of the outposts of empire, the half-made societies, as Naipaul calls them. They share a similarity of outlook: the darkness of human irrationality, aggression, fanaticism, and barbarism are always impending; and that civilization is an achievement that has to be worked at constantly. Naipaul also explores how the social order comes to bear on the lives of individuals, defining our possibilities, constraining and enabling our individuality, and affecting how each one of us lives and understands and values his single life.

Naipaul, like Conrad, believes in mankind’s corruptibility. Naipaul, however, departs from the Conradian view of the world as locked forever under darkness. In an essay entitled, Conrad’s Darkness, Naipaul writes, “Conrad’s value to me is that he is someone who sixty to seventy years ago meditated on my world, a world I recognize today. I feel this about no other writer of the century” (“Conrad’s Darkness,” in The Return of Eva Peron with The Killings in Trinidad.1980. p. 219).

The world has changed, however, between the days in which Conrad wrote and the period in which Naipaul lives. Both authors had direct experience with the colonial world and explore this world in their novels, but Naipaul, 75 years Conrad’s junior, also witnessed the decline of colonialism as it gave rise to the post-colonial world. Thus, Naipaul stands in a more historically advanced position from which he evaluates the world. His advantage of living in a later historical period than Conrad allows him to see consequences and outcomes that Conrad could not foresee. This historical advantage of perspective may account in part for Naipaul’s less pessimistic assessment of the human condition.

A House for Mr. Biswas

Set in an Indian community in Trinidad, A House for Mr. Biswas, arguably Naipaul’s greatest work, documents Mohan Biswas’s quest for dignity in a society that is unwilling to recognize his value as an individual. From the beginning, Mr. Biswas must combat prejudices and preconceived notions about his identity. The novel follows his quest for respect, independence, and a house to call his own as he challenges these prejudices and the culture which refuses to recognize him. Only the narrator accords Mr. Biswas the respect he deserves by referring to him with the title “Mr.” throughout the novel.

Mr. Biswas is born into a world that does not receive him kindly. He has been “[b]orn in the wrong way,” has six fingers, and enters the world at midnight, “the inauspicious hour.” The pundit declares that he will have an unlucky sneeze and warns that evil will result if Mr. Biswas goes near trees or water. His father is not pleased with the birth of his son or the pundit’s pronouncements, but he simply accepts his lot in life according to his philosophy: “Fate. There is nothing we can do about it.” It is against this prevailing attitude that Mr. Biswas must battle throughout the novel, for Mr. Biswas desires to make things happen for himself, to reject the prejudicial beliefs of his society and to cast off the superstitions surrounding his name.

Like the Hegelian individual, Mr. Biswas opposes fatalism and desires to achieve a free self-consciousness through work and through the recognition of others. The preconceived notions of his society, however, act as obstacles to Mr. Biswas’s realization of his individual worth. When his father drowns in a pond, Mr. Biswas (still a child) is blamed because he has gone near the water in violation of the pundit’s warning. The death of Mr. Biswas’s father sets off a series of events that eventually force his mother to sell their house. The narrator relates, “And so Mr. Biswas came to leave the only house to which he had some right. For the next thirty-five years he was to be a wanderer with no place he could call his own.” Furthermore, his family splits up to live with various relatives, and as a result, Mr. Biswas feels very alone in the world.

When Mr. Biswas marries, he becomes enslaved by the Tulsis, his wife’s relatives, for many years. Mr. Biswas is not literally a slave in the strictest sense of the term, but he repeatedly tells his wife that her family has “trapped” him. The Tulsis own a store and a large house called Hanuman House. When the narrator describes the house, he creates the impression of a large communal society. Children seem to run wildly and rampantly throughout the residence, adults seem to be engaged in constant quarrels, and a peculiar code of human behavior that emphasizes a perverted equality dominates the household.

Unable to bear the imposition upon his dignity and his independence, Mr. Biswas moves to a place known as “The Chase,” where he escapes from Hanuman House but not from the dominating presence of the Tulsis. The Chase proves ultimately unsatisfactory to Mr. Biswas; he begins to regard the venture as something “temporary and not quite real.” He reasons that “[r]eal life was to begin for them soon, and elsewhere. The Chase was a pause, a preparation.” As it turns out, the pause is a long one.

In the meanwhile, Mr. Biswas begins to lose sight of his dream as his individuality is smothered by the presence of the Tulsis and by other limiting influences on his freedom. He stops reading Samuel Smiles. The mention of ‘Smiles’ is important: Samuel Smiles was a Scottish author famous for books on self-help, and he promoted the idea that more progress would come from new attitudes than from new laws.

He does not give up hope, however, and he retains the sense that “some nobler purpose awaited him, even in this limiting society.” When Mr. Biswas leaves The Chase, he moves to a place called Green Vale, where he works as a sub-overseer in the sugarcane fields. Still, he has not escaped the shadow of the Tulsis; Green Vale is, after all, “part of the Tulsis land just outside of Arwacus.” It is “considered almost an extension of Hanuman House.” The Tulsis repeatedly work against Mr. Biswas’s attempts to assert himself as an individual. They seem particularly adverse to the idea of Mr. Biswas having a house of his own. Even when Mr. Biswas purchases a dollhouse for his daughter, the relatives at Hanuman House become resentful of this possession and treat Mr. Biswas’s wife so terribly that she eventually smashes the house to alleviate the situation. When the dollhouse is smashed along with Mr. Biswas’s dignity, the relatives are happy again. Here we see the nature and limits of traditional societies as it was ruthlessly and unsentimentally documented by Naipaul, including the emasculation of men in traditional patriarchal societies as opposed to free societies.

In what ways does Mr. Biswas battle throughout the novel to make things happen for himself, to reject the prejudicial beliefs of his society and to cast off the superstitions surrounding his name? When Mr. Biswas’s mother dies and the doctor acts rudely in writing her certificate of death, Mr. Biswas writes a letter of protest to the doctor. The letter is structured around the theme “no one could escape from what he was” and concludes that “no one could deny his humanity and keep his self-respect.” This letter is a personal declaration of independence.

Mr. Biswas finds a vehicle toward independence in education. He is an avid reader, and he stresses the importance of learning to his children, particularly to his son Anand. When the Tulsis come into financial difficulties and must sell their house, education acquires a new significance in the absence of the security of a closed community: “There was no longer a Hanuman House to protect them; everyone had to fight for himself in a new world, the world Owar and Shekhar had entered, where education was the only protection.” As the dominating presence of the Tulsis fades, Mr. Biswas begins to obtain a greater sense of dignity. His dignity is constantly insulted, but Mr. Biswas preserves his self-respect.

Eventually, Mr. Biswas acquires the means to purchase a house that is truly his own. The purchase of his house symbolizes the purchase of his freedom. He no longer remains constrained under the Tulsis’ shadow. The house on Sikkim Street has its disadvantages; the staircase is plain and unstable, the windows downstairs do not close, the doors upstairs lack uniformity, and other imperfections are discovered as well. However, the house acquires significance more for what it accomplishes than for what it lacks. Most importantly, it gives Mr. Biswas and his family an identity that reflects their independence. Thus the house, as a new arena of independence, provides a replacement for the old days of dependency. Mr. Biswas dies with a house of his own, in a world where he has earned his freedom and established his individuality.

Our Universal Civilization

Do people from non-Western (European) cultures come, in time, to adopt autonomy (and its nexus of beliefs) as a value? One way of answering this question is to examine the work of Nobel Prize winning author V. S. Naipaul. Naipaul answers in the affirmative. He does so in an important essay entitled, “Our Universal Civilization.”

In 1990, Naipaul delivered a speech at the Manhattan Institute in which he outlined his concept of “Our Universal Civilization.” Myron Magnet, the Senior Fellow of the Institute, introduced him as “Conrad’s spiritual heir.” As outsiders who came to England only after their childhood years, both Conrad and Naipaul “share a certain history that makes them almost obsessive analysts and questioners of social reality.” Naipaul in particular “explores the intersection of the social order and the individual life” and examines how the social order defines “our possibilities,” constrains and enables “our individuality,” and affects “how each one of us lives and understands and values his single life.” Thus, the nature of the relationship between society and the individual becomes a crucial one in the development of self-consciousness and the understanding of personal autonomy.

Hegel’s conception of freedom posits a continually advancing civilization in which humans progress toward a greater understanding of freedom; Naipaul insist that civilization is an advancement contingent upon human effort. Conrad and Naipaul, Magnet states, “share a similarity of outlook” in that they both view “the bush or the darkness of human irrationality, aggression, fanaticism, and barbarism” as “always impending.” For both authors, “civilization is an achievement that has to be worked at constantly.” For Conrad, the darkness forms a continual presence that perpetually overshadows society; the world for Conrad is a world of illusion in which humans ultimately cannot escape from the darkness. For Naipaul, however, human improvement is a reality; he sees society as advancing, and it is this optimistic view of civilization’s future that separates him from Conrad. If there is a sense in which Naipaul is writing in Conrad’s shadow, there is also a sense in which he escapes from it.

Naipaul’s speech serves to highlight the extent to which Naipaul, as Conrad’s inheritor, also diverges from him. At the conclusion of his lecture, Naipaul prophesies that the Western idea, which embodies the pursuit of happiness, individuality, and other liberal virtues, will cause “other more rigid systems in the end [to] blow away.” Naipaul, like Conrad, believes in mankind’s corruptibility. Unlike Conrad, however, Naipaul also believes in mankind’s perfectibility. Thus Naipaul departs from the Conradian worldview of the world as locked forever under darkness.

Naipaul also acknowledges his debt to Conrad; he does not reject him, but rather diverges from him. In an essay entitled, Conrad’s Darkness, Naipaul writes, “Conrad’s value to me is that he is someone who sixty to seventy years ago meditated on my world, a world I recognize today. I feel this about no other writer of the century.” The world has changed, however, between the days in which Conrad wrote and the period in which Naipaul lives. Both authors had direct experiences within the colonial world and explore this world in their novels, but Naipaul, 75 years Conrad’s junior, also witnessed the decline of colonialism as it gave rise to the post-colonial world. Thus, Naipaul stands in a more historically advanced position from which he evaluates the world. His advantage of living in a later historical period than Conrad allows him to see consequences and outcomes that Conrad could not foresee. This historical advantage of perspective may account in part for Naipaul’s less pessimistic assessment of the human condition and his more optimistic outlook regarding the future of society.

The universal civilization has been a long time in the making. It wasn’t always universal; it wasn’t always as attractive as it is today. The expansion of Europe gave it for at least three centuries a racial taint, which still causes pain. In Trinidad, I grew up in the last days of that kind of racialism. And that, perhaps, has given me a greater appreciation of the immense changes that have taken place since the end of the war, the extraordinary attempt of this civilization to accommodate the rest of the world, and all the currents of that world’s thought… A later realization—I suppose I have sensed it most of my life, but I have understood it philosophically only during the preparation of this talk—has been the beauty of the idea of the pursuit of happiness. Familiar words, easy to take for granted; easy to misconstrue. This idea of the pursuit of happiness is at the heart of the attractiveness of the civilization to so many outside it or on its periphery. I find it marvelous to contemplate to what an extent, after two centuries, and after the terrible history of the earlier part of this century, the idea has come to a kind of fruition. It is an elastic idea; it fits all men. It implies a certain kind of society, a certain kind of awakened spirit. I don’t imagine my father’s parents would have been able to understand the idea. So much is contained in it: the idea of the individual, responsibility, choice, the life of the intellect, the idea of vocation and perfectibility and achievement. It is an immense human idea. It cannot be reduced to a fixed system. It cannot generate fanaticism. But it is known to exist; and because of that, other more rigid systems in the end blow away.

For Naipaul, then, personal autonomy becomes an important issue. However, individuals also have the responsibility of working on their own freedom; they cannot gain a sense of self-consciousness solely through the means of another individual. Naipaul, like Hegel (and Oakeshott), criticizes the anti-individual who refuses to form an identity apart from the group. In a Free State in particular he addresses the issue of the post-colonial subject who does not know how to form an identity apart from his master or a larger society. In a Free State consists of two short stories (One out of Many and Tell Me Who to Kill) and a short novel (In a Free State) surrounded by a prologue and an epilogue from Naipaul’s travel journals.

In One out of Many, however, Naipaul suggests that some people may not be ready to accept their own freedom; the realization of self-consciousness is a rewarding but painful and difficult process. The first-person narrator in One out of Many encounters this very difficulty. Born and raised in Bombay, the narrator, Santosh, works for the government and can only conceive of his identity insofar as it relates to his employer; the narrator has no identity outside of the identity he associates with his master. Santosh relates, “I experienced the world through him… I was content to be a small part of his presence.” When his employer is transferred to Washington, the “capital of the world,” Santosh begs for permission to accompany him. His employer agrees. Initially, Santosh retains the characteristics of the Oakeshottian anti-individual who, finding himself “saddled with the unsought and inescapable ‘freedom’ of human agency,” is hesitant about being able to respond.

At first, Washington and the new American culture overwhelms Santosh. Gradually, however, he comes to gain a sense of his own individuality: “Now I found, that, without wishing it, I was ceasing to see myself as part of my employer’s presence, and beginning at the same time to see him as an outsider might see him, as perhaps the people who came to dinner in the apartment saw him.” As his sense of agency emerges, Santosh resolves to run away from his employer. After wandering the streets of Washington, Santosh takes on a new job at a restaurant owned by a man named Priya. In this new position, Santosh reflects upon his discovery of freedom: “I felt I was earning my freedom. Though I was in hiding, and though I worked every day until midnight, I felt I was much more in charge of myself than I had ever been.” Thus labor, in Naipaul as well as in Hegel, serves as a means by which individuals develop a sense of their own agency.

This freedom, however, also implies an increase in responsibilities. For Santosh, the freedom he discovers at Priya’s restaurant presents complications: “It was worse than being in the apartment, because now the responsibility was mine and mine alone. I had decided to be free, to act for myself.” Santosh begins to regret the consequences of his freedom, and one day he calls Priya, with whom he has developed a close and friendly relationship, “sahib.” Overwhelmed by the sense of his own freedom, Santosh retreats back into the position of servant by referring to his friend Priya in this way:

I had used the wrong word. Once I had used the word a hundred times a day. But then I had considered myself a small part of my employer’s presence, and the word was not servile; it was more like a name, like a reassuring sound, part of my employer’s dignity and therefore part of mine. But Priya’s dignity could never be mine; that was not our relationship. Priya I had always called Priya; it was his wish, the American way, man to man. With Priya the word was servile. And he responded to the word.… I never called him by his name again.… I was a free man; I had lost my freedom.

While Naipaul approves of the American way of treating and addressing others as equals, he also realizes that the transition into such a culture is not an easy process, especially for one who comes from a background of strict class systems where servility to superiors is taught as a virtue, or as a necessary means of communication.

At the end of the story, Santosh becomes an American citizen, but he does not want to live in the American way. For him, the transition from sleeping outside on the street with his friends in Bombay to living in America is too great to rightly be called pleasant. At the same time, however, America has given Santosh freedom; in America, he realizes that he is free; he becomes self-conscious of his freedom. He realizes that he made the decision to come to Washington and that he cannot return to the ways of Bombay. Santosh concludes his tale with an evaluation of his freedom:

I was once part of the flow, never thinking of myself as a presence. Then I looked in the mirror and decided to be free. All that my freedom has brought me is the knowledge that I have a face and a body, that I must feed this body and clothe this body for a certain number of years. Then it will all be over.

Thus, Santosh delivers a troubling diagnosis of freedom. He acknowledges the negative side of freedom, in which duties associated with freedom become a burden. Nevertheless, Santosh’s final and disappointing portrait of freedom does not imply Naipaul’s approval of slavery or servitude. Rather, Naipaul wishes to expose the side of freedom that often gets undervalued; he wishes to show that freedom carries with it responsibilities, and that certain people have trouble accepting those responsibilities. For Naipaul, an individual’s enjoyment of freedom depends upon what that individual makes of his freedom. In this respect, Naipaul’s argument parallels Hegel’s assertion in the Philosophy of Right: “On the one hand, it is true that every individual has an independent existence [ist jades Individuum für sich]; but on the other, the individual is also a member of the system of civil society, and just as every human being has a right to demand a livelihood from society, so also must society protect him from himself…. Since civil society is obliged to feed its members, it also has the right to urge them to provide for their own livelihood.”

He would also agree with Hegel’s assertion in the Philosophy of Right: “If the direct burden [of support] were to fall on the wealthier class, or if direct means were available in other public institutions (such as wealthy hospitals, foundations, or monasteries) to maintain the increasingly impoverished mass at its normal standard of living, the livelihood of the needy would be ensured without the mediation of work; this would be contrary to the principle of civil society and the feeling of self-sufficiency and honor among its individual members.”

The narrator of Tell Me Who to Kill resolves to ensure his younger brother’s education. However, the narrator makes a mistake in assuming responsibility for his brother; while his encouragement is commendatory, the narrator ultimately cannot control his brother’s actions or make his brother succeed in the Western world. When Dayo, the narrator’s younger brother, goes to college in London, he struggles to adjust to his new lifestyle but fails. The narrator, moves to London and obtains a job in order to assist Dayo financially, but neither the narrator’s financial assistance nor even his emotional presence can substitute for Dayo’s own agency.

The narrator cannot help an individual who is not willing to help himself. The narrator’s misconception results in his disillusionment with the world around him as he fails to understand Dayo’s loss of confidence and motivation. The short story ends with Dayo’s marriage, which the narrator describes as “more like a funeral than a wedding.” The narrator cannot make sense of his surroundings, of unexpected outcomes, or of his failed plan to give Dayo a European education. Angry at the world, he wonders “who to kill.”

In In a Free State, Naipaul explores the alternative to Western rule. Set in Africa shortly after the end of British imperialism, In a Free State explores the political consequences of independence. “In ‘The Loss of El Dorado,’ Naipaul is unsparing about the abuses of colonial rule. But he’s not oblivious to what followed: “corrupt and brutal despotisms in Africa and South America, stupid homegrown ideologies, as well as the self-indulgent Western fantasies that sustain them.” Writing about Egypt in his epilogue, Naipaul exclaims, “Peonies, China! So many empires had come here.” He is looking at postcards of Chinese flowers that have been handed out as gifts to waiters in a small Egyptian hut. The implication is that Africa is still a land of conquest, where the Chinese are now establishing an empire, albeit “more remote,” in Egypt through their commercial activity.

If history is a history of conquest, it is also a history of change, and the nature of this change has resulted in more opportunities for humans to discover their freedom. A Bend in the River suggests, more strongly than A House for Mr. Biswas or In a Free State, that the Western enterprise has altered the world forever, and that this change has created a new sphere in which humans can best realize the meaning of freedom. A Bend in the River presents a decidedly more optimistic view of the human condition than the two former novels. The novel centers around Salim, an Indian man who opens a shop at the bend of a river in a newly independent African state. The geographic location (that is to say, Africa) is the same as in In a Free State, and political turmoil also plays a role here, but in A Bend in the River Naipaul expresses greater hope for the inhabitants of Developing countries and the opportunities available to them.

Salim, the narrator and main character, begins with the statement “The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.” This statement in many ways sums up Naipaul’s philosophy on life. It emphasizes the role that individuals play in their own fate and advocates personal responsibility in the face of a world that will not automatically adjust to fit individuals’ needs or desires. The opening statement of A Bend in the River also precludes anyone from blaming the world for personal failures; it denounces men who are not proactive. It is a negatively expressed statement, but it has a positive converse. For Naipaul, individuals have to make their dreams happen. If men who make themselves nothing have no place in the world, then men who make something of themselves do have a place in the world.

In the opening chapters of the novel, Salim offers a history of his family. His family past consists of men who would likely fall into the category of “men who are nothing.” They are not ambitious men, but rather men who had accepted without question the customs and traditions of their land:

We simply lived; we did what was expected of us, what we had seen the previous generation do. We never asked why; we never recorded. We felt in our bones that we were a very old people; but we seemed to have no means of gauging the passing of time. Neither my father nor my grandfather could put dates to their stories. Not because they had forgotten or were confused; the past was simply the past.

Salim’s ancestors, then, lack a clear conception of their larger historical significance. They also do not possess a conception of time; Salim’s journey into his family history, like Marlow’s journey up the Congo River, is a journey into a realm where time ceases to have a functional meaning. This limited conception of time reflects the primitive state of mankind before the advent of modern civilization. It also suggests that history involves a development of the mind. In this way, Naipaul’s recording of the narrator’s family history reflects a Hegelian approach to world history.

Salim’s ancestors locate themselves in the present and think even less of the future than they do of the past. “In our family house when I was a child I never heard a discussion about our future or the future of the coast. The assumption seemed to be that things would continue, that marriages would continue to be arranged between approved parties, that trade and business would go on, that Africa would be for us as it had been.”

Unlike his relatives, however, Salim has a sense of his society’s relationship to the rest of the world. “But it came to me when I was quite young, still at school, that our way of life was antiquated and almost at an end…” British postage stamps with a picture of an Arab dhow – what a foreigner describes as “most striking about this place [in Africa]”—generate Salim’s sense of societal self-consciousness, and he develops “the habit of looking, detaching myself from a familiar scene and trying to consider it as from a distance.”

Salim’s process of both recognizing himself as a part of his environment and also of perceiving himself as separate from his environment matches Hegel’s conception of the self-conscious individual who perceives that he is “a member of the system of civil society” but also realizes that he has an “independent existence.”

From this perspective of an outsider who is simultaneously an insider, Salim develops the idea that “as a community we had fallen behind.” The quality of self-consciousness and the ability to “stand back and consider the nature” of one’s community becomes crucial in an individual’s as well as a culture’s adjustment to the changing world. Salim observes, that the Europeans “were better equipped to cope with changes than we were” because “they could assess themselves.” Thus, the Europeans have an advantage over inhabitants of countries/cultures who have not advanced as far in the development of self-consciousness.

Salim perceives that the world around him is changing, and that if he is to succeed in it, he must take action. This action involves breaking away from the limiting lifestyles of his heritage:

I had to break away from our family compound and our community. To stay with my community, to pretend that I had simply to travel along with them, was to be taken with them to destruction. I could be master of my fate only if I stood alone. One tide of history… had brought us here…. Now… another tide of history was going to wash us away.

Salim resolves to leave his Indian community on the coast of Africa and journey inland to set up a new life, where he will run a shop on the bend in the river. The bend in the river symbolically represents the change in times, the switch from one historical epoch to another.

The “tides of history” concept which Naipaul invokes also recalls Hegel, who ascribes certain moments of the world mind’s Idea to certain epochs in history. In the Philosophy of Right he states that each stage of world history is “the presence of a necessary moment in the Idea of the world mind,” and he ascribes this Idea to particular nations.

The nation to which is ascribed a moment of the Idea in the form of a natural principle is entrusted with giving complete effect to it in the advance of the self-developing self-consciousness of the world mind. This nation is dominant in world history during this one epoch, and it is only once that it can make its hour strike. In contrast with this its absolute right of being the vehicle of the present stage in the world mind’s development, the minds of the other nations are without rights, and they, along with those whose hour has struck already, count no longer in world history.

Insofar as a particular nation possesses the Idea of the world mind, it has the right to promulgate this idea and promote historical development.

Naipaul presents a similar argument, although he makes a few modifications to the original Hegelian view. In A Bend in the River, Europe – and, more broadly, the West—acts as the vehicle of the present stage in history. If A Bend in the River had to locate this vehicle in a particular nation, it would likely be England, which is representative of the Western idea in the novel. Nevertheless, Naipaul certainly advances the Hegelian argument that certain ideas gain power and even right in the flow of history. In his speech before the Manhattan Institute, Naipaul characterizes this Western idea more specifically as “the idea of the pursuit of happiness.” Naipaul calls this pursuit “an immense human idea;” contained within it is “the idea of the individual, responsibility, choice, the life of the intellect, the idea of vocation and perfectibility and achievement.” Naipaul claims that this idea “has come to a kind of fruition.” In his 1979 novel, Naipaul traces the development of this idea toward its fruition. Furthermore, as the novel progresses, Salim comes to recognize the beauty and the enabling power of this Western idea. As in Hegel, Western thought parallels the individual mind in the history of its development.

When Salim in A Bend in the River finds that his country can no longer accommodate his newfound freedom, Salim is compelled to flee Africa in order to escape the new, oppressive regime that his taken over his shop and threatens to obliterate his identity as well. The novel ends with Salim’s flight, and on one level this seems like a negative and depressing conclusion. This interpretation, however, misses a crucial point: Salim is leaving a land of oppression to enter a land of opportunity. Salim’s visit to London before his permanent departure has already given him insight into the kind of opportunities available outside of his small African community. After his enlightenment, Salim realizes that there can be “no going back” to his former way of life. “[T]here was nothing to go back to. We had become to what the world outside had made us; we had to live in the world as it existed.” His friend Indar has introduced Salim to European ways of thinking and has revealed to Salim the flaws in traditional, non-Western thought. Indar tells Salim,

We have no means of understanding a fraction of the thought and science and philosophy and law that have gone to make that outside world. We simply accept it. We have grown up paying tribute to it, and that is what most of us do. We feel of the great world that it is simply there, something for the lucky ones among us to explore, and then only at the edges. It never occurs to us that we might make some contribution to it ourselves. And that is why we miss everything.

By the end of the novel, Salim has come to the conclusion that he does have power over his own fate and that he will no longer let himself be restricted by the limiting paradigms of a preceding generation. His decision to leave Africa parallels Naipaul’s own decision to leave his native Trinidad for the larger world in which he could better express his freedom. Like Salim, Naipaul saw “the rituals and the myths” of his heritage “at a distance” and eventually decided to leave Trinidad because his homeland did not offer “that kind of society” in which “the writing life was possible.” He had to make a journey “from the margin to the center” in order to find a society that would accommodate his needs, and this journey necessitated leaving his old life.

When Salim flees Africa at the end of the novel, he is not facing defeat, or a life of lonely exile. He is leaving a land that has limited his freedom to join other people in other lands who will share his freedom with him.

In A Bend in the River, the narrator (an Indian who lives in postcolonial Africa) observes, “[I]t came to me while I was still quite young, still at school, that our way of life was antiquated and almost at an end.” He later comes to regard himself “as part of an immense flow of history” in which the old and primitive cultures give way to the power of the European idea. The Europeans, he relates, “gave us on the coast some idea of our history.” The introduction of Western ideas to non-Western cultures precipitates a change in the living conditions of those cultures that affects not only physical surroundings but also the attitudes and philosophies of a land’s inhabitants.

Naipaul’s works embody the Hegelian conception of freedom and the human condition; like Hegel, Naipaul advocates individual freedom coupled with individual responsibility. He also acknowledges the value of ideas, and specifically the Western idea. Naipaul’s works is itself an immense contribution to the evolution of Western thought.

Nicholas Capaldi is Professor Emeritus at Loyola University, New Orleans.