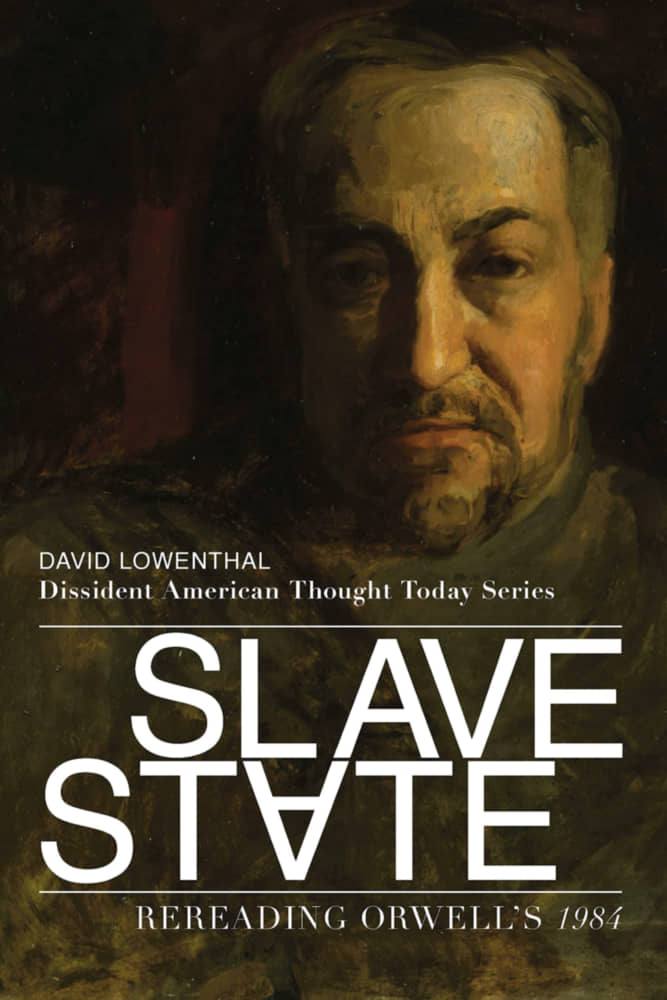

Here is an excerpt, through the kind courtesy of St. Augustine’s Press, from an absorbing study, Slave State. Rereading Orwell’s 1984, by David Lowenthal, in which present society is transposed onto Orwell’s dystopia, in order to illustrate “how the quest for a perfect society led instead to the worst.”

What many understand by instinct, Lowenthal here articulates in clear terms, using the political prophesy of this no longer futuristic work, to describe our descent into enslavement. But Orwell provides no positive political message, argues Lowenthal, but there is a positive moral message that is nearly always overlooked by commentators, which the reader slowly discovers upon reading this excellent work: “With the decline of Christianity’s influence in forming the moral sense of the West and the concomitant increase in power hunger, wielding instruments born of modern enlightenment, what mankind most needed was moral guidance, conveyed not abstractly, through philosophy, but in such a way as to grip the whole soul.”

Lowenthal echoes Orwell when he says, “we have abandoned inculcating good citizenship, higher ideals and a sense of personal worth in the schools, encouraging instead an aimless low-level conformist ‘individuality’ just waiting to be harnessed together and directed. Given these conditions, can we be sure we have left the conditions to the horrors of 1984 far behind as mere fiction?”

Make sure to pick up a copy and share it with you family and friends.

****

I first learned of George Orwell through the letters he wrote from London for The Partisan Review during World War II. I loved him then and I love him still. Whatever he did had the touch of an independent mind and a noble soul. Nobody could write more clearly. Nobody felt more deeply and sincerely for the underdog. Nobody had as much to say about the problems pressing humanity. No one did more to appreciate the achievements of modernity while facing its grim realities. Nobody made a greater effort to rise above the petty orthodoxies of the left toward a better general appreciation of liberal society and his own England. None of the literary people gave nearly as much independent thought to the standards that should guide human life and must guide it in the dark days ahead.

1984 was published in 1949, shortly after Orwell’s death. For decades it was considered the classic portrayal of communist totalitarianism and taught in the schools as such. After the collapse of the Soviet Union its popularity waned—not even to be revived by Solzhenitsyn’s description of the horrors of Soviet communism. Solzhenitsyn wrote as a Russian patriot and a Christian, Orwell as a democratic socialist who shared the vision of Western liberal enlightenment and was perplexed, as much as he was appalled, by the growth of totalitarianism and the totalitarian mentality in the twentieth century. We can see why communism absorbed his thought much more than Nazism or fascism. While all three had much in common, communism claimed to be the final extension of reason in the name of liberty and equality—i.e., in the name of human brotherhood rather than drastic inequality. How, at the very moment when science and technology promised the final liberation of mankind, could communism turn mankind toward its universal, complete, and perpetual enslavement, culminating in an earthly hell rather than an earthly paradise?

1984 is an attempt to answer this question. But, beyond this, and at least equally important, it is an attempt to guide mankind in the dark days ahead—the dark ages ahead—which, in the aftermath of atomic war, Orwell considered not simply possible but most likely. There is no positive political message in 1984: the closest to it comes in the appendix on Newspeak, where the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence (“We hold these truths to be self-evident, etc.”) is used to demonstrate language from the pre-revolutionary world that cannot be translated into Newspeak. But there is a positive moral message—one often missed by commentators because, unlike Goldstein’s extensive treatise on oligarchical collectivism, it is woven into the fabric of the novel as a whole—into its characters, their words, their actions. Through the movement of the novel, Orwell tries to impress on the passions, hearts, and minds of his readers the most valuable lessons concerning the right and wrong way to live. With the decline of Christianity’s influence in forming the moral sense of the West and the concomitant increase in power hunger, wielding instruments born of modern enlightenment, what mankind most needed was moral guidance, conveyed not abstractly, through philosophy, but in such a way as to grip the whole soul.

This moral teaching, this “humanist ethic,” as Orwell calls it elsewhere, was his greatest bequest to mankind. It sought to care for intellectuals and masses alike, for the heroic and the common, for the aristocratic “Winston” and the democratic “Smith”—as the name of his protagonist itself suggests. Based on the study of human nature and the discovery of man’s good in his nature, it tries to convey a palpable knowledge of good and evil and thus to assure the passing on of the human heritage from hand to hand or mouth to mouth should the threatening blackness engulf us. Understanding this teaching along with the deeper causes of the tyranny is the prime objects of this study, consequent to which—apart from a brief opening sketch—only minimal attention will be given to the details of Orwell’s life or to those many writings that do not bear directly on our subject.

Orwell was a literary man of the left, an intellectual but not an ordinary one. He suffered from the rupture between literature and philosophy that afflicts both to this day and, while few knew modern literature better, he had little taste for the abstractions of philosophy and knew little of the ancient or modern political philosophers who could have helped him most. Yet his thinking points toward philosophy, needs it for its beginnings, development, and completion. Properly under- stood it can even serve as a bridge to philosophy, and that’s how I regard it here. But first we must be sure we see the real Orwell, the full Orwell, and that requires some doing. He was a much more systematic thinker than he is given credit for— an adverse opinion easily come by since he wrote so many different things without ever systematically summing up his thought.

I have tried to examine these writings under relevant heads to ascertain his moral and political views by the time he wrote 1984. And because there’s no substitute for his own words, I have cited passages copiously, often from writings the reader might find it difficult to obtain for himself. As we wit- ness the intellectual process by which Orwell ultimately abandons the Marxism with which he began, we come upon countless themes and issues of great currency today on which I shall not myself dwell, leaving it to the thoughtful reader to consider these ties to the contemporary. My own comments will occur briefly from time to time and are mostly suggestive in nature.

Lest we be tempted to dismiss Orwell’s account of the totalitarian regime in 1984 as of merely historical interest, let us ask ourselves whether the conditions lending support to that regime have completely disappeared. First, regarding the work’s premise of nuclear war, has that possibility declined or in- creased with the current and prospective proliferation of nu- clear might? Do we know what human life would be like in its aftermath? Have we not already discovered means of wreaking havoc even worse than the atom bomb itself? Is not Communist China consciously preparing to overtake, overcome, and perhaps overthrow our liberal society? At the same time, a much greater centralization of power has occurred here. As for devices watching and controlling us, we have already gone be- yond the capacities used so coercively in 1984. Nor can we re- ally think the totalitarian mentality a thing of the past, with so much evidence to the contrary regularly displayed in so many ways—on college campuses, at rock concerts, in ordinary political life.

The massing of people in cities and the grip of modern industry, the spread of drugs, and wealth itself have taken their toll and left us more prone to the siren calls of false hero- ism. There’s much more crowd behavior, much less independent thought. The sense of personal worth, virtue, and privacy itself has been eroded by the mass media. With the decline of religious beliefs and feelings and out of narrow self-interest many have even come to welcome late-term abortions. With the help of technical advances the sexual impulse, already widely emancipated and promoted by the purveyors of intellect as they battered down the walls of religion, wreaked havoc on the family and left rootless individuals in their place.

Many of the educated, influenced by relativism in its many forms, have lost confidence in the liberal principles that in the world of 1984 have been completely effaced. This is especially true on college campuses, where faculty, administration, and students collaborate in fostering a radical contempt for their own country. At the same time we have abandoned inculcating good citizenship, higher ideals, and a sense of personal worth in the schools, encouraging instead an aimless low-level conformist “individuality” just waiting to be harnessed together and directed. Given these conditions, can we be sure we have left the conditions leading to the horrors of 1984 far behind as mere fiction?

David Lowenthal is retired professor of political philosophy. He is author of Present Dangers, Shakespeare’s Thought, and The Mind and Art of Abraham Lincoln, Philosopher Statesman.